1 Submission to the Standing Committee on Infrastructure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Gina Rinehart 2. Anthony Pratt & Family • 3. Harry Triguboff

1. Gina Rinehart $14.02billion from Resources Chairman – Hancock Prospecting Residence: Perth Wealth last year: $20.01b Rank last year: 1 A plunging iron ore price has made a big dent in Gina Rinehart’s wealth. But so vast are her mining assets that Rinehart, chairman of Hancock Prospecting, maintains her position as Australia’s richest person in 2015. Work is continuing on her $10billion Roy Hill project in Western Australia, although it has been hit by doubts over its short-term viability given falling commodity prices and safety issues. Rinehart is pressing ahead and expects the first shipment late in 2015. Most of her wealth comes from huge royalty cheques from Rio Tinto, which mines vast swaths of tenements pegged by Rinehart’s late father, Lang Hancock, in the 1950s and 1960s. Rinehart's wealth has been subject to a long running family dispute with a court ruling in May that eldest daughter Bianca should become head of the $5b family trust. 2. Anthony Pratt & Family $10.76billion from manufacturing and investment Executive Chairman – Visy Residence: Melbourne Wealth last year: $7.6billion Rank last year: 2 Anthony Pratt’s bet on a recovering United States economy is paying off. The value of his US-based Pratt Industries has surged this year thanks to an improving manufacturing sector and a lower Australian dollar. Pratt is also executive chairman of box maker and recycling business Visy, based in Melbourne. Visy is Australia’s largest private company by revenue and the biggest Australian-owned employer in the US. Pratt inherited the Visy leadership from his late father Richard in 2009, though the firm’s ownership is shared with sisters Heloise Waislitz and Fiona Geminder. -

The Fairfax Women and the Arts and Crafts Movement, 1899-1914

CHAPTER 2 - FROM NEEDLEWORK TO WOODCARVING: THE FAIRFAX WOMEN AND THE ARTS AND CRAFTS MOVEMENT, 1899-1914 By the beginning of the twentieth century, the various campaigns of the women's movement had begun to affect the lives of non-campaigners. As seen in the previous chapter activists directly encouraged individual women who would profit from and aid the acquisition of new opportunities for women. Yet a broader mass of women had already experienced an increase in educational and professional freedom, had acquired constitutional acknowledgment of the right to national womanhood suffrage, and in some cases had actually obtained state suffrage. While these in the end were qualified victories, they did have an impact on the activities and lifestyles of middle-class Australian women. Some women laid claim to an increased level of cultural agency. The arts appeared to fall into that twilight zone where mid-Victorian stereotypes of feminine behaviour were maintained in some respects, while the boundaries of professionalism and leadership, and the hierarchy of artistic genres were interrogated by women. Many women had absorbed the cultural values taken to denote middle-class respectability in Britain, and sought to create a sense of refinement within their own homes. Both the 'new woman' and the conservative matriarch moved beyond a passive appreciation and domestic application of those arts, to a more active role as public promoters or creators of culture. Where Miles Franklin fell between the two stools of nationalism and feminism, the women at the forefront of the arts and crafts movement in Sydney merged national and imperial influences with Victorian and Edwardian conceptions of womanhood. -

Orielton Park Homestead Estate Landscape Conservation Management Plan Prepared by Tropman & Tropman Architects

Orielton Park Homestead Estate 183 The Northern Road, Harrington Park, NSW Landscape Conservation Management Plan prepared for Dandaloo Developments Pty Ltd NSW SEPTEMBER 2017 REF: 1321: LCMP Issue 06 Tropman & Tropman Architects Architecture Conservation Landscape Interiors Urban Design Interpretation 55 Lower Fort Street Sydney NSW 2000 Phone: (02) 9251 3250 Fax: (02) 9251 6109 Website: www.tropmanarchitects.com.au Email: [email protected] TROPMAN AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ABN 71 088 542 885 INCORPORATED IN NEW SOUTH WALES Lester Tropman Architects Registration: 3786 John Tropman Architects Registration: 5152 Tropman & Tropman Architects i Orielton Park Homestead Estate Ref: 1321: LCMP Landscape Conservation Management Plan SEPTEMBER 2017 Report Register The following table is a report register tracking the issues of the Orielton Park Homestead Estate Landscape Conservation Management Plan prepared by Tropman & Tropman Architects. Tropman & Tropman Architects operate under a quality management system, and this register is in compliance with this system. Project Issue Description Prepared Checked Issued To Issue Date Ref No. No. by by 1321:LCMP 01 Draft Orielton Park Lester Lester Terry Goldacre 16.01.14 Homestead Estate Tropman Tropman Trevor Jensen Landscape Conservation Joanne By Email Management Plan Lloyd Draft Orielton Park Lester Lester Terry Goldacre November 1321:LCMP 02 Homestead Estate Tropman Tropman Trevor Jensen 2014 Landscape Conservation Linda By Email Management Plan Storey Orielton Park Homestead Lester Lester -

Consuming Master-Planned Estates in Australia: Political, Social, Cultural and Economic Factors

Consuming Master-Planned Estates in Australia: Political, Social, Cultural and Economic Factors Kamel Taoum Submitted in Fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Urban Research Centre School of Social Sciences and Psychology University of Western Sydney Australia March 2015 i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………...vii Statement of Authentication ........................................................................................... viii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. ix Dedication ........................................................................................................................... x Chapter 1 Introduction and Background ......................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Statement of the Problem ................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Aims and Objectives of the thesis .................................................................................... 6 Chapter 2 MPEs Development and Consumption: History and Literature Review ... 10 2.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 10 2.1.1 History of MPEs ..................................................................................................... -

The Rich in the Depression

2 The Rich in the Depression DOMESTIC SERVICE IN WOOLLAHRA DURING THE DEPRESSION YEARS, 1928-1934 DREW COTTLE work on changing australia There has been a common response when interviewing elderly working people about there experiences during the Depression: the working people indeed suffered, bllt the rich continued, as before, to remain the rich. Or, as one ex-domestic remarked, " To the rich there was no depression" (D. Shaw, conv ersation, 12. 5.1976) . One could brush this remark aside as yet another myth about the Depression ... Dn the other hand, the remark could be taken as a fact and investigated. The following investigation is based on interviews with a number of people who had been domestic servants in the homes of the woollahra wealthy during the De pression . Their testimony is a stimulating glimpse of how this elite fared at a time of "equal sacrifice". In addition, it provides for an account of the daily life and outlook of Sydney domestic servants, the social history of a strata of workers , mainly women , which had been all but neglected in vol.l no.l other t racts on the De pression. 3 Contents Research int o domestic service in Australia has been negligible. Indeed, it was not until the publication of B. Kingston's My wife, My Daughter and Poor Mary Ann,l that a serious study of warnen in domes tic service was undertaken. An examination of domestic service at the 1 ... Editor ial local l evel, therefore, will obviously be full of difficulties and errors. This exploration of darestic service, hO\Yever, will not discuss 2 .. -

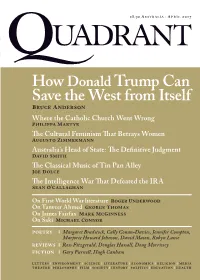

How Donald Trump Can Save the West from Itself

27/09/2016 10:23 AM 10:23 27/09/2016 (03) 9320 9065 9320 (03) $44.95 (03) 8317 8147 8147 8317 (03) fAX Quadrant, 2/5 Rosebery Place, Balmain NSW 2041, Australia 2041, NSW Balmain Place, Rosebery 2/5 Quadrant, phone quadrant.org.au/shop/ poST political fabrications. political online Constitution denied them full citizenship are are citizenship full them denied Constitution for you, or AS A gifT A AS or you, for including the right to vote. Claims that the the that Claims vote. to right the including 33011_QBooks_Ads_V5.indd 1 33011_QBooks_Ads_V5.indd had the same political rights as other Australians, Australians, other as rights political same the had The great majority of Aboriginal people have always always have people Aboriginal of majority great The Australia the most democratic country in the world. world. the in country democratic most the Australia At Federation in 1901, our Constitution made made Constitution our 1901, in Federation At peoples from the Australian nation. This is a myth. myth. a is This nation. Australian the from peoples drafted to exclude Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Islander Strait Torres and Aboriginal exclude to drafted Australian people by claiming our Constitution was was Constitution our claiming by people Australian nation complete; it will divide us permanently. permanently. us divide will it complete; nation University-based lawyers are misleading the the misleading are lawyers University-based its ‘launching pad’. Recognition will not make our our make not will Recognition pad’. ‘launching its on The conSTiTuTion conSTiTuTion The on Constitutional recognition, if passed, would be be would passed, if recognition, Constitutional The AcAdemic ASSAulT ASSAulT AcAdemic The of the whole Australian continent. -

Australian Newspaper History: a Bibliography

Australian Newspaper History: A Bibliography Compiled by Victor Isaacs, Rod Kirkpatrick and John Russell. First published in 2004 by Australian Newspaper History Group 13 Sumac Street Middle Park Queensland 4074 © Australian Newspaper History group This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher. A cataloguing record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia. Isaacs, Victor, 1949 –, and Kirkpatrick, Rod, 1943 – , and Russell, John, 1939 – Australian Newspaper History: A Bibliography ISBN 0-9751552-1-0 Printed in Australia by Snap Printing, Sumner Park, Queensland. 2 The compilers This bibliography is another product of the active minds belonging to key members of the Australian Newspaper History Group. The founder of the group, Victor Isaacs, was the inspiration for the bibliography. Isaacs, of Canberra, has interests in newspaper, political and railway history. Rod Kirkpatrick, of Brisbane, is a journalism educator, newspaper historian, former provincial daily newspaper editor and the author of histories of the provincial presses of Queensland and New South Wales. He has nearly completed writing a history of the national provincial daily press. He is the Program Director, Journalism, in the School of Journalism and Communication, University of Queensland, Brisbane. John Russell, of Canberra, has interests in the history of colonial printing and publishing especially newspapers and periodicals, the role of women, and labour in print. The compilers would be pleased to hear of additional entries and corrections. -

Commemorating the Life of Lady Mary Fairfax

Commemorating the life of Lady Mary Fairfax Harrington Park, Harrington Grove and Catherine Park Estate all stand proudly as part of the rich legacy left by Lady Mary Fairfax. ady (Mary) Fairfax AC OBE passed away at her family home, Fairwater, in September last year Lat the age of 95. She was instrumental in the development of Harrington Park and Harrington Grove. It was their vision to build a place for families to live comfortably, spaciously and surrounded by the lush scenery that brought them so much pleasure on their visits to the area. Early Life and From Double Bay Public Persona to Harrington Park Along with her parents, Marie Wein (later changed The link between Fairwater, the Fairfax family home, to Mary) fled Jewish persecution and political in Double Bay and Harrington Park was forged instability in Poland as a child in the mid-1920s, in 1944 when Sir Warwick purchased the cattle arriving in Australia. She grew into a woman of quick property on which Harrington Park House stood. The wit, intelligence and business acumen, studying home quickly became his weekend retreat, and he Chemistry at the University of Sydney, assisting her would travel the 60 km from the city to Harrington parents with their fashion boutiques and working as Park on Friday nights before making his way back a part-time pharmacist. again in time for the working week. Lady Mary, the children and the family dogs also loved heading out Lady Mary was a socialite, businesswoman to the property, enjoying walks, picnics, swims in and philanthropist. -

John Fairfax and the Sydney Morning Herald, 1841-1877

The Shaping of Colonial Liberalism: John Fairfax and the Sydney Morning Herald, 1841-1877. A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of New South Wales 2006 Stuart Buchanan Johnson ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed ……………………………………………........................... COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only).