Cumorah Gordan Holdaway (CH), 395 S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITY COUNCIL MEETING 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah September 11, 2018

CITY OF OREM CITY COUNCIL MEETING 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah September 11, 2018 This meeting may be held electronically to allow a Councilmember to participate. 4:30 P.M. WORK SESSION - CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM PRESENTATION - North Pointe Solid Waste Special Service District (30 min) Presenter: Brenn Bybee and Rodger Harper DISCUSSION - SCERA Shell Study (15 min) Presenter: Steven Downs 5:00 P.M. STUDY SESSION - CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM 1. PREVIEW UPCOMING AGENDA ITEMS Staff will present to the City Council a preview of upcoming agenda items. 2. AGENDA REVIEW The City Council will review the items on the agenda. 3. CITY COUNCIL - NEW BUSINESS This is an opportunity for members of the City Council to raise issues of information or concern. 6:00 P.M. REGULAR SESSION - COUNCIL CHAMBERS 4. CALL TO ORDER 5. INVOCATION/INSPIRATIONAL THOUGHT: BY INVITATION 6. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE: BY INVITATION 7. PATRIOT DAY OBSERVANCE 7.1. PATRIOT DAY 2018 - In remembrance of 9/11 To honor those whose lives were lost or changed forever in the attacks on September 11, 2001, we will observe a moment of silence. Please stand and join us. 1 8. APPROVAL OF MINUTES 8.1. MINUTES - August 14, 2018 City Council Meeting MINUTES - August 28, 2018 City Council Meeting For review and approval 2018-08-14.ccmin DRAFT.docx 2018-08-28.ccmin DRAFT.docx 9. MAYOR’S REPORT/ITEMS REFERRED BY COUNCIL 9.1. APPOINTMENTS TO BOARDS AND COMMISSIONS Beautification Advisory Commission - Elaine Parker Senior Advisory Commission - Ernst Hlawatschek Applications for vacancies on boards and commissions for review and appointment Elaine Parker_BAC.pdf Ernst Hlawatschek_SrAC.pdf 10. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Royal Skousen Royal Skousen

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Royal Skousen Fundamental Scholarly Discoveries and Academic Accomplishments listed in an addendum first placed online in 2014 plus an additional statement regarding the Book of Mormon Critical Text Project from November 2014 through December 2018 13 May 2020 O in 2017-2020 in progress Royal Skousen Professor of Linguistics and English Language 4037 JFSB Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 [email protected] 801-422-3482 (office, with phone mail) 801-422-0906 (fax) personal born 5 August 1945 in Cleveland, Ohio married to Sirkku Unelma Härkönen, 24 June 1968 7 children 2 education 1963 graduated from Sunset High School, Beaverton, Oregon 1969 BA (major in English, minor in mathematics), Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 1971 MA (linguistics), University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois 1972 PhD (linguistics), University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois teaching positions 1970-1972 instructor of the introductory and advanced graduate courses in mathematical linguistics, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois 1972-1979 assistant professor of linguistics, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 1979-1981 assistant professor of English and linguistics, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 1981-1986 associate professor of English and linguistics, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 1986-2001 professor of English and linguistics, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah O 2001-2018 professor of linguistics and English language, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 2007-2010 associate chair, -

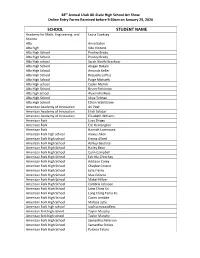

School Student Name

48th Annual Utah All-State High School Art Show Online Entry Forms Received before 9:30am on January 25, 2020 SCHOOL STUDENT NAME Academy for Math, Engineering, and Laura Cooksey Science Alta Anna Eaton Alta high Vito Vincent Alta High School Presley Brady Alta High School Presley Brady Alta High school Sarah Noelle Brashear Alta High School Abigail Hakala Alta High School Amanda Keller Alta High School Raquelle Loftiss Alta High School Paige Michaels Alta High school Caden Myrick Alta High School Brynn Parkinson Alta high school Alyxandra Rees Alta High School Miya Tolman Alta High School Ethan Wahlstrom American Academy of Innovation Ari Peel American Academy of Innovation Erick Salazar American Academy of Innovation Elisabeth Williams American Fork Lizzy Driggs American Fork Elle Kennington American Fork Hannah Lorenzana American Fork high school Alexus Allen American Fork High school Emma Allred American Fork High School Ashley Bautista American Fork High School Hailey Bean American Fork High School Colin Campbell American Fork High School Estrella Chinchay American Fork High School Addison Corey American Fork High School Chaylee Coston American Fork High School Julia Fierro American Fork High School Max Giforos American Fork High School Mabel Hillyer American Fork High School Cambria Johnson American Fork High School Long Ching Ko American Fork High School Long Ching Tania Ko American Fork High School Casen Lembke American Fork High School Malissa Lytle American Fork high school sophia mccandless American fork high school Taylor -

Newletter Template

Week of January 20th, 2020 Alta High School Ignite the Hawk Within We are an inclusive learning community with a tradition of inspiring, supporting, and collaborating with students as they prepare to be engaged citizens in their pursuit of continuous success. ü Step2TheU Program – It is time for Alta’s 11th grade students to start considering applying for our Step2TheU Program. For more information, please visit the Step2TheU webpage. Applications are due February 3, 2020. You can also order your transcripts by going online here or through the Alta website. Please allow 2 business days to process your request. ü Interested in Concurrent Enrollment? – Join us for an informational meeting on January 21st. See additional page for more details. ü After School Tutoring – At Alta, we provide many options for students to obtain help if they are struggling in one or more of their classes. Please visit the After School Tutoring page on the Alta website for more information. You can also view a schedule for Math Lab and Computer Lab below. ü Girls and Boys State – Applications for Girls and Boys State are now available to all 11th grade students. This is a great opportunity to earn college credit, learn about government and citizenship and spend time with students from all over the state. This looks great on college and scholarship applications! Space is limited for these programs, so you will want to apply today. The application deadline for Girls State is February 10th. Boys State applications are due in April. See the additional pages for more information. Application information is also available in the Alta Counseling Office. -

(School Resource Officers) This Agreement Is Executed in Duplicate

AMENDED INTERLOCAL AGREEMENT (School Resource Officers) This Agreement is executed in duplicate this ____ day of ______________________, 2018, by and between the City of Orem, a municipal corporation and political subdivision of the State of Utah, with its principal offices located at 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah 84057, (hereinafter referred to as the “City”), and the Board of Education, Alpine School District, a corporation and political subdivision of the State of Utah, with its principal offices located at 575 North 100 East, American Fork, Utah 84003 (hereinafter referred to as “Alpine”). WHEREAS, Alpine was created for the purpose of educating, training, developing, and ensuring the academic excellence of the youth of its district; and WHEREAS, Alpine has established a reputation for excellence in the quality of its schools and the resulting level of achievement by its students; and WHEREAS, juvenile crime and school violence continues to escalate nationally and in the State of Utah and without appropriate intervention, youthful offenders are more likely to repeat and even increase their level of criminal activity; and WHEREAS, youth can sometimes be a disruptive influence on others as their involvement in gang and criminal activity is carried onto the school campus; and WHEREAS, the resulting cost to both victims and the criminal justice system becomes an increasing burden to the community; and WHEREAS, Alpine and the City are mutually supportive of efforts to engage in activities which promote the prevention and detection -

Alumni Magazine Fall 2011 Alumni Magazine

Sweet Dream Celebrating the MBA Program’s Eyewitness to the The Interns Come True p 4 Golden Anniversary p 10 Japan Earthquake p 14 Take Manhattan p 20 alumni magazine 2011 fall alumni magazine Issue Fall 2011 marriottschool.byu.edu PublIsher Gary C. Cornia ManagIng edItor Joseph D. Ogden edItor Emily Smurthwaite art dIrector Jon G. Woidka coPy edItors Jenifer Greenwood Lena Harper ContrIbutIng edItor Nina Whitehead assIstant edItors Michelle Kaiser Angela Marler contrIbutIng wrIters, edItors, Carrie Akinaka desIgners, & PhotograPhers Robert G. Gardner Aaron Garza Sara Harding Chadwick Little Courtney Rieder Nielsen Michael Smart Sarah Tomoser MagazIne desIgn BYU Publications & Graphics all coMMunIcatIon should be sent to Marriott Alumni Magazine 490 Tanner Building Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602-3187 Phone: 801-422-7696 fax: 801-422-0501 eMaIl: [email protected] MarrIott aluMnI MagazIne Is PublIshed by the MarrIott school of ManageMent at brIghaM young unIversIty, Provo, utah. the vIews exPressed In MarrIott aluMnI MagazIne are not necessarIly endorsed by byu or the church of Jesus chrIst of latter-day saInts. coPyrIght 2011 by brIghaM young unIversIty. all rIghts reserved. fInd thIs and Past Issues of MarrIott aluMnI MagazIne onlIne at marriottmag.byu.edu MeMbers of the MarrIott school’s natIonal advIsory councIl gather In front of fenway Park’s faMed green Monster at the nac sPrIng retreat In boston. Hi, are you here yet? OK, just walk down that huge set of silver stairs. You can’t miss them—they look like the stairway to heaven. • So what are you going to do? I’ll text you. Why? I’m right here! Just tell me now. -

Utah Valley University Men's Basketball

2017-18 GAME NOTES | GAME 19 UTAH VALLEY UNIVERSITY MEN’S BASKETBALL Jason Erickson | Assistant AD - Communications | E: [email protected] | C: 303-946-6774 | O: 801-863-5451 2017-18 SCHEDULE UTAH VALLEY(13-5, 2-0) vs. CHICAGO STATE (2-17, 0-2) Overall: 13-5 | Home: 10-1 | Away: 3-4 | WAC: 0-0 SATURDAY, JAN. 13, 2018 | 7 P.m. (MST) | OREM, UTAH | UCCU CENTER Date Opponent Time/Result Nov. 01 Dixie State (Exh.) W, 81-70 Location .................................................................. Orem, Utah UTAH VALLEY WOLVERINES Nov. 10 at #4 Kentucky (SEC Network) L, 63-73 Site ........................................................... UCCU Center (7,500) Head Coach .................. Mark Pope Nov. 11 at #1 Duke (ACC Network Extra) L, 69-99 TV .........UVUtv/WAC Digital Network (Brandon Crow/Holton Hunsaker) Alma Mater .............. Kentucky, ‘96 Career Record (Yr.) ...... 42-40 (3rd) Nov. 14 at Idaho State (BigSkyTV) W, 84-71 Live Video ..................................................WACsports.com/live Nov. 18 UC Davis (UVUtv/WDN) W, 80-71 Record at UVU (Yr.) .............. Same Radio ...............................................ESPN 960 AM (Jim McCulloch) Nov. 20 Eastern Oregon (WDN) W, 97-52 Live Audio .................................................ESPN960Sports.com Nov. 25 at North Dakota (BigSkyTV) W, 83-75 (OT) CHICAGO STATE COUGARS Live Stats ..............................................................UVUstats.com Nov. 29 BYU (BYUtv/ESPN3) L, 58-85 Head Coach ...................Tracy Dildy All-Time Series ......................................... UVU leads series, 9-7 Alma Mater .............................UIC, ‘97 Dec. 02 UTSA (UVUtv/WDN) W, 88-80 UVU Streak ...........................................................................W5 Career Record (Yr.) ....54-188 (8th) Dec. 06 Weber State (UVUtv/WDN) W, 83-56 UMKC Streak ..........................................................................L1 Record at CSU (Yr.) ............... Same Dec. 09 at Cal State Fullerton (BigWest.tv) L, 83-91 Dec. -

Utah High School Activities Assoctiation Yearly Results

UTAH HIGH SCHOOL ACTIVITIES ASSOCTIATION YEARLY RESULTS 2010-2011 UTAH HIGH SCHOOL ACTIVITIES ASSOCIATION YEARLY RESULTS 2010-2011 SPORTS BASEBALL ........................................................................................................................................3 BOYS BASKETBALL ...........................................................................................................................8 GIRLS BASKETBALL .........................................................................................................................13 BOYS CROSS COUNTRY ...................................................................................................................18 GIRLS CROSS COUNTRY ...................................................................................................................21 DRILL TEAM ...................................................................................................................................24 FOOTBALL ......................................................................................................................................26 BOYS GOLF ....................................................................................................................................31 GIRLS GOLF ...................................................................................................................................33 BOYS SOCCER .................................................................................................................................35 -

Joann D. Bartoletti DATE

TO: State Executive Directors FROM: JoAnn D. Bartoletti DATE: February 9, 2016 RE: Prudential Spirit of Community Awards I am happy to inform you that the search for this year’s top youth volunteers is now complete, and the Prudential Spirit of Community Awards program will announce today each state’s top high school and middle level honoree. Sponsored by Prudential in partnership with the National Association of Secondary School Principals, the program recognizes middle level and high school students for their outstanding community service. Over the past 20 years, more than 100,000 students have been honored at the local, state and national levels. Enclosed is the National Press Release announcing the top middle level and high school volunteers. I encourage you to share it with your local media outlets. At a time when more and more attention is being placed on community service, this program is an outstanding example of how we can honor our young volunteers and help develop role models for others. The program is supported by the following organizations: American Association of School Administrators; American Red Cross; America’s Promise; Association for Middle Level Education; Council of the Great City Schools; Girl Scouts; HandsOn Network; National 4-H Council; National Association for Music Educators; National School Boards Association; National School Public Relations Association; PTA; and YMCA of the USA. Thank you for your support in making the 2016 Prudential Spirit of Community Awards successful. Please call Ann Postlewaite at 703-860-7238 or email at [email protected], if you have any questions. Enclosure: National Press Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Harold Banks, Prudential Financial, (973) 802-8974 February 9, 2016 or (973) 216-4833 or [email protected] TOP YOUTH VOLUNTEERS IN EACH STATE SELECTED IN 21st ANNUAL NATIONAL AWARDS PROGRAM 102 student volunteers earn $1,000 awards, silver medallions and trip to nation’s capital WASHINGTON, D.C. -

BYU Baseball

BYU Baseball Athletic Communications • 30 Smith Fieldhouse • Provo, UT, 84602 Contact: Ralph Zobell • Office: (801) 422-9769 • Fax: (801) 422-0633 e-mail: [email protected] BYU (20-15, 7-5) vs. Utah (13-18, 3-9) BYU 2009 Schedule/Results Date Opponent Time at site of game Probable BYU Pitching Rotation 2/ 20 Manhattan College W, 11-10 Apr. 17 Utah Jeremy Toole (5-2, 3.59) 6 p.m. 2/ 20 @ No. 13 Oklahoma St. L, 14-17 2/ 21 Manhattan College L, 6-20 Apr. 18 Utah Blake Torgerson (4-2, 5.62) 1 p.m. 2/ 21 @ No. 13 Oklahoma St. L, 4-5 Apr. 18 Utah Adam Miller (3-2,3.86) 5 p.m. 2/23 @ No. 6 Baylor L, 6-7 2/26 Portland +^ W, 10-2 2/27 Portland +^ L, 3-8 2/28 Portland + W, 10-3 Series Records: 3/2 @Wichita St. +%^ L, 5-6 BYU has a 210-93-1 record against the University of Utah. BYU’s 3/3 @Wichita St. +%^ W, 3-1 3/6 St. John’s + ^(BYUTV) W, 5-4 greatest and longest standing rivalry--with the University of Utah--did 3/7 St. John’s +^ (BYUTV) W, 6-5 not start on the football field. On May 18, 1895, the Brigham Young 3/7 St. John’s + (11 innings) W, 8-7 3/10 Southern Utah +^ (BYUTV) W, 8-3 Academy played the first ever intercollegiate event in Utah against the 3/12 @ Utah * W, 4-1 Utes on a baseball diamond. The game ended in a 0-0 tie and a bench- 3/13 Utah *+^ (BYUTV) L, 13-15 3/14 Utah *+^ (BYUTV) W, 11-3 clearing brawl. -

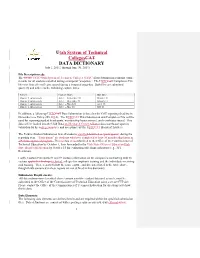

Utah System of Technical Collegescat DATA DICTIONARY July 1, 20167 Through June 30, 20178

Utah System of Technical CollegesCAT DATA DICTIONARY July 1, 20167 through June 30, 20178 File Descriptions: ds The UCAT USTC Utah System of Technical Colleges (USTC) Data Submission contains course records for all students enrolled during a temporal “snapshot.” The USTCCAT Completers File likewise lists all certificates issued during a temporal snapshot. Both files are submitted quarterly and adhere to the following capture dates: Report Capture Dates Due Date Quarter 1 submissions July 1 – September 30 October 15 Quarter 2 submissions July 1 – December 31 January 15 Quarter 3 submissions July 1 – March 31 April 15 Quarter 4 submissions July 1 – June 30 July 31 In addition, a follow-up USTCCAT Data Submission is due after the COE reporting deadline in December (see Policy 205.110.2). The USTCCAT Data Submission and Completers File will be used for reporting student headcounts, membership hours accrued, and certificates issued. This data will be loaded into the Utah Data and Research Center Alliance data warehouse upon its validation by the collegesampuses and acceptance by the USTCCAT Board of Trustees. The Perkins Student Submission lists all students enrolledidentified as “participants” during the reporting year. “Participants” are students who have completed at least 30 membership hours in a Perkins-approved program. Theseis data areis submitted to the Office of the Commissioner of Technical Education by October 1, then forwarded to the Utah State Office of EducationUtah State Board of Education by October 15 for evaluation of Perkins indicators (e.g., 3P1 – Retention). Lastly, Custom Fit reports #1 and #2 contain information on the companies contracting with the various applied technology technical colleges for employee training and the individuals receiving said training. -

CITY of OREM PLANNING COMMISSION MEETING 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah August 22, 2018

CITY OF OREM PLANNING COMMISSION MEETING 56 North State Street, Orem, Utah August 22, 2018 This meeting may be held electronically to allow a Councilmember to participate. 3:30 PM PRE-MEETING – AGENDA REVIEW, CITY COUNCIL CONFERENCE ROOM, 56 NORTH STATE STREET, OREM, UT 4:30 PM REGULAR SESSION – CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. INVOCATION BY INVITATION 3. 4:30 PM SCHEDULED ITEMS 3.1. The applicant requests preliminary plat approval for The Farm Plat B located at 580 South 200 West in the R8 zone. Staff recommends the Planning Commission approve the preliminary plat for The Farm Plat B located at 580 South 200 West in the R8 zone. The_Farm_Staff_Report (4).docx Zoning Map.pdf The Farm Plat B.pdf The Farm MailerBack.pdf 3.2. 2018 Orem City General Plan Adoption Send a recommendation to City Council regarding the adoption of the 2018 Orem City General Plan and appendices. Commission_General_Plan_Update_StaffReport_2018.08.22.docx Orem General Plan 2018_2018.08.16.pdf Orem Moderate-Income Housing Study_2018.08.16.pdf 4. 5:00 PM SCHEDULED ITEMS 5. MINUTES REVIEW AND APPROVAL 5.1. August 1, 2018 Planning Commission Minutes Approval 2018-08-01.pcmin DRAFT.docx 1 6. ADJOURN Next meeting scheduled for Wednesday, September 5, 2018 THE PUBLIC IS INVITED TO PARTICIPATE IN ALL CITY COUNCIL MEETINGS. If you need a special accommodation to participate in the City Council Meetings and Study Sessions, please call the City Recorder's Office at least 3 working days prior to the meeting. (Voice 801-229-7000) This agenda is also available on the City's webpage at orem.org 2 2 Agenda Item No: 3.1 Planning Commission Agenda Item Report Meeting Date: August 22, 2018 Submitted by: Kristina Haycock Submitting Department: Development Services Item Type: Site Plan Agenda Section: 4:30 PM Scheduled Items Subject: The applicant requests preliminary plat approval for The Farm Plat B located at 580 South 200 West in the R8 zone.