NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY the Electoral Success And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report of the Vermont Tax Structure Commission

2021 Final Report of the Vermont Tax Structure Commission PREPARED IN ACCORDANCE WITH ACT 11, SEC. H.17 OF THE 2018 SPECIAL LEGISLATIVE SESSION DEB BRIGHTON, STEPHEN TRENHOLM, BRAM KLEPPNER VERMONT TAX STRUCTURE COMMISSION | February 8, 2021 Table of Contents i 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 2. Summary of Recommendations ........................................................................................... 4 Recommendation 1: Undertake Tax Incidence Analysis in Order to Eliminate Tax Burden/Benefit Cliffs ............................................................................................................ 4 Recommendation 2: Establish an Ongoing Education Tax Advisory Committee ..................... 5 Recommendation 3: Restructure the Homestead Education Tax ............................................. 5 Recommendation 4: Broaden the Sales Tax Base ..................................................................... 7 Recommendation 5: Modernize Income Tax Features ............................................................... 8 Recommendation 6: Improve Administration of Property Tax ................................................. 8 Recommendation 7: Create a Comprehensive Telecommunications Tax ................................. 9 Recommendation 8: Utilize Tax Policy to Address Climate Change ........................................10 Recommendation 9: Collaborate With Other States to Build a Fairer, More -

APPROVED Kentucky Association of Chiefs of Police EXECUTIVE BOARD / GENERAL MEMBERSHIP MEETING Elizabethtown, Kentucky February 2Nd, 2017 10:30 A.M

APPROVED Kentucky Association of Chiefs of Police EXECUTIVE BOARD / GENERAL MEMBERSHIP MEETING Elizabethtown, Kentucky February 2nd, 2017 10:30 a.m. MINUTES 1. Call to order, President Barnhill 2. Roll Call by Director Pendegraff, quorum present to conduct business. In attendance from the Executive Board were: Chief Brandon Barnhill, Chief Tracy Schiller, Chief Tony Lucas, Chief Art Ealum, Chief Guy Howie, Ex. Dir. Jim Pendergraff, Chief Rob Ratliff, Chief Deputy Joe Cline, Chief Wayne Turner, Chief Doug Nelson, Chief Victor Shifflett, Chief Frank Cates, Chief David Gregory, Chief Kelly Spratt, Director Josh Crain, Chief Andy Midkiff, SAIC Richard Ferretti, Chief Wayne Hall, Chief Howard Langston, Commissioner Mark Filburn, Commissioner Rick Sanders, Chief Mike Ward, and Chief Shawn Butler. Absent were: Chief Doug Hamilton, Chief Mike Daly, Chief Todd Kelley, Chief Mike Thomas, Chief Bill Crider, and Chief Allen Love. 3. Introduction of Guests; Dr. Noelle Hunter, KOHS Pat Crowley, Strategic Advisers 4. Pat Crowley and Chief Turner presented a report on the Legislative Session: BILLS SUPPORTING Senate SB 26 - Sen. John Schickel, R-Union An Act related to operator's license testing Amend KRS 186.480 to require the Department of Kentucky State Police to make a driver's manual available in printed or electronic format that contains the information needed for an operator's license examination; require that the manual have a section regarding an applicant's conduct during interactions with law enforcement officers; require that the operator's license examination include the applicant's knowledge regarding conduct during interactions with law enforcement officers. SB 31 (Senate version of KLEFPF) - Sen. -

Become a State Political Coordinator

STATE POLITICAL COORDINATOR GUIDEBOOK State Political Coordinator Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 SPC Duties and Expectations………………………………………………..……………………………………..…………….4 SPC Dos and Don’ts……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 Fostering a Relationship with your Legislator…………………………………………………………………………….6 Calls For Action…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……7 How a Bill Becomes Law…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Glossary of Legislative Terms……………………………………………..……………………………………….…………..10 Resources and Contact Information………………………………………………………………………………………...13 Directory of State Senators……………………………………………….……………………………………………………..14 Directory of State Representatives…………………………………………………………………………………………..17 SPC Checklist……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………24 KENTUCKY REALTORS® 2 State Political Coordinator Manual INTRODUCTION State Political Coordinators (SPCs) play an important role in advancing the legislative priorities of Kentucky REALTORS® (KYR) members across the Commonwealth. KYR is the voice homeownership and real property rights and the SPCs are the loudspeaker that help amplify that message to every corner of the state. Each SPC is tasked with creating and cultivating a direct relationship with their State Representative or Senator. Through those relationships, SPCs educate their respective member on key issues and act as a consistent point of contact for any industry-related questions. Candidates for SPC should have interest in politics and legislation, -

So Far, All Signs Point to the National Nuclear Renaissance Passing by New England

NUCLEAR OPTION Vermont Yankee, a nuclear power plant on the Connecticut River, is up for re-licensing, a process that in Vermont requires the Legislature’s approval. POWER POLITICS SO FAR, ALL SIGNS POINT TO THE NATIONAL NUCLEAR RENAISSANCE PASSING BY NEW ENGLAND. [ BY BARBARA MORAN ] n February 24, Randy Brock, a Republican state sena- friendly, and reliable and wants the plant to stay open. But a series of prob- tor in Vermont, did something he never expected to lems at Vermont Yankee forced his hand. “If their board of directors and do. He voted to close Vermont Yankee, the state’s its management had been thoroughly infiltrated by anti-nuclear activists,” only nuclear power plant. A longtime supporter he says, “they could not have done a better job destroying their own case.” of the plant, Brock did not want to vote this way. Vermonters – including the senator – were fed up with the way the plant He considers nuclear power safe, environmentally was being run, so he voted no. PRESS/ ASSOCIATED BY PHOTOGRAPH PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION STAFF GLOBE ENTERGY; 16 THE BOSTON GLOBE MAGAZINE MAY 9, 2010 POWER POLITICS The Vermont vote, coming just a week after President Barack Obama States since the Three Mile Island reactor accident in 1979 (several opened announced $8.33 billion in federal loan guarantees for companies building after the accident), in other countries – France in particular, and China – two new nuclear reactors in Georgia, would seem to show a New England nuclear power is increasingly common, and new technologies that create stuck in the no-nukes 1980s, out of step with the nuclear fever sweeping less waste and offer better containment have lowered the risk of environ- the rest of the country. -

State Association of Nonprofits Presents Advocacy Awards to Members and Legislators

For Immediate Release February 8, 2019 Contact: Danielle Clore (859) 963-3203 x3 [email protected] www.kynonprofits.org State Association of Nonprofits Presents Advocacy Awards to Members and Legislators (FRANKFORT, Ky.—) Kentucky Nonprofit Network, the state association of nonprofit organizations, presented three member organizations and current and former legislators with awards as part of its 14th annual Kentucky Nonprofit Day at the Capitol in Frankfort on February 7. The annual event provides nonprofit organizations statewide with the opportunity to meet legislators and support Kentucky Nonprofit Network’s advocacy program to advance the sector. The awards presented include the Nonprofit Voice Awards, recognizing KNN members for their demonstrated excellence in public policy during the 2018 General Assembly, and the Nonprofit Advocacy Partner Awards, recognizing legislators and officials for their support of the members’ efforts. Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky of Louisville received a Nonprofit Voice Award for its work to raise the cigarette tax in Kentucky in an effort to curb smoking and improve the health of Kentuckians. House Bill 366 included a $.50 per pack tax increase on cigarettes, which recent polling revealed has resulted in 39 percent of Kentucky smokers cutting back. Senators Julie Raque Adams of Louisville and Ralph Alvarado of Winchester, Representative Steven Rudy of Paducah and former Representative Addia Wuchner of Florence were presented Nonprofit Advocacy Partner awards for their support of the effort. -

Refer to This List for Area Legislators and Candidates

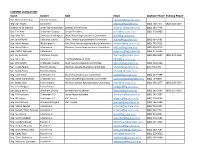

CURRENT LEGISLATORS Name District Role Email Daytime Phone Evening Phone Sen. Richard Westman Lamoille County [email protected] Rep. Dan Noyes Lamoille-2 [email protected] (802) 730-7171 (802) 644-2297 Speaker Mitzi Johnson Grand Isle-Chittenden Speaker of the House [email protected] (802) 363-4448 Sen. Tim Ashe Chittenden County Senate President [email protected] (802) 318-0903 Rep. Kitty Toll Caledona-Washington Chair, House Appropriations Committee [email protected] Sen. Jane Kitchel Caledonia County Chair, Senate Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 684-3482 Rep. Mary Hooper Washington-4 Vice Chair, House Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 793-9512 Rep. Marty Feltus Caledonia-4 Member, House Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 626-9516 Rep. Patrick Seymour Caledonia-4 [email protected] (802) 274-5000 Sen. Joe Benning Caledonia County [email protected] (802) 626-3600 (802) 274-1346 Rep. Matt Hill Lamoille 2 *NOT RUNNING IN 2020 [email protected] Sen. Phil Baruth Chittenden County Chair, Senate Education Committee [email protected] (802) 503-5266 Sen. Corey Parent Franklin County Member, Senate Education Committee [email protected] 802-370-0494 Sen. Randy Brock Franklin County [email protected] Rep. Kate Webb Chittenden 5-1 Chair, House Education Committee [email protected] (802) 233-7798 Rep. Dylan Giambatista Chittenden 8-2 House Leadership/Education Committee [email protected] (802) 734-8841 Sen. Bobby Starr Essex-Orleans Member, Senate Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 988-2877 (802) 309-3354 Sen. -

KMA 2021 Advocacy Achievement Report

2021 ACHIEVEMENT REPORT KMA WRAPS HISTORICALLY SUCCESSFUL SESSION FOR PHYSICIANS AND PATIENTS Despite challenges related to the COVID-19 KMA Priorities That Passed pandemic and several inclement weather House Bill 140, sponsored by Rep. Deanna Frazier, expands the delays, the Kentucky Medical Association definition of telehealth to include remote patient monitoring and (KMA) wrapped up one of its most successful addresses broadband access and smart devise barriers in the sessions in recent years, with five priority state by allowing telehealth services to continue through audio- only encounters. Additionally, the legislation removes the face- issues being sent to the Governor’s desk and to-face restriction for certain behavioral health services becoming law. permitting these services to be continued to be delivered via telehealth after the expiration of the public health emergency. The Kentucky General Assembly convened on Tuesday, Due to a change in the Senate, the final version of the legislation January 5, for the short, 30-day legislative session, and retains the current language in state law, which calls for legislators hit the ground running with a fast-paced and payment parity unless the telehealth provider and the aggressive agenda. During the first eight days of the session, commercial health plan or Medicaid MCO negotiate a lower rate. legislators addressed issues arising from the coronavirus pandemic, including revisions to KRS Chapter 39A, which sets House Bill 50, sponsored by Rep. Kim Moser, requires insurers forth the governor’s powers during a declared emergency. to demonstrate compliance with federal law in how they design and apply managed care techniques for behavioral and mental Most notably, lawmakers enacted the following three bills prior to health treatment to ensure coverage is no more restrictive than the January recess, and ultimately, had to override gubernatorial for any other medical condition. -

Caledonia County Choose

2016 Gun Owners of Vermont Voter Guide CALEDONIA COUNTY CHOOSE Contest District Party Name On Ballot For President National Republican DONALD TRUMP: MIXED Vice President National Republican MIKE PENCE: STRONG PRO 2A For President National Libertarian GARY JOHNSON: STRONG PRO 2A Vice President National Libertarian WILLIAM F. WELD: ANTI-GUN For US Senate National United States Marijuana CRIS ERICSON For US Senate National Liberty Union PETE DIAMONDSTONE State Level Candidates Contest District Party Name On Ballot For Governor State Republican PHIL SCOTT For Lieutenant Governor State Republican RANDY BROCK Secretary of State State Democratic / Republican JIM CONDOS For Auditor of Accounts State Republican DAN FELICIANO For Attorney General State Republican DEBORAH 'DEB' BUCKNAM Local Level Candidates Vote For Is candidate Contest District Party Name On Ballot # Pro or Anti? For State Senate Caledonia STRONG PRO Republican JOE BENNING ONLY 1 (incumbent) Senate 2A Caledonia For State Senate MARIJUANA GALEN DIVELY III UNKNOWN Senate For State Senate Caledonia Democratic JANE KITCHEL ANTI-GUN (incumbent) Senate For State Representative MARCIA ROBINSON STRONG PRO Caledonia-1 Republican (incumbent) MARTEL 2A ONLY 1 ONLY 1 For State Representative Caledonia-2 Republican LAWRENCE W. HAMEL PRO 2A For State Representative STRONG PRO Caledonia-3 Republican JANSSEN WILLHOIT (incumbent) 2A ONLY 2 Updated 11/6/16 http://www.gunownersofvermont.org/wordpress/research-analysis/Candidates/Candidate_Reports.htm For State Representative Caledonia-3 Republican -

Page 1 of 12 2017 Legislature February 11, 2017 HB 12 Rep. Sannie Overly (D) Require

2017 Legislature February 11, 2017 HB 12 http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/17RS/HB12.htm Rep. Sannie Overly (D) Require a consumer-reporting agency to place a security freeze on a protected person's record or report upon proper request by a representative. Cf. SB 19 Jan 3-introduced in House; to Banking & Insurance (H) HB 33 http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/17RS/HB33.htm Rep. Kim King (R) Require CHFS, if the cabinet is granted custody of a child, to notify the school in which the child is enrolled of persons authorized to contact the child or remove the child from school grounds. Similar bills were filed in the last three regular legislative sessions (16RS HB 47; 15RS HB 30; 14RS HB 44), but none of the bills made it out of committee. Jan 3-introduced in House; to Health & Family Services (H) HB 47 http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/17RS/HB47.htm Rep. Dennis Keene (D) Establish a public central registry for child abuse and neglect. A similar bill (16 RS HB 475) was filed he last regular session; it passed the House, but did not make it out of the Senate. Cf. HB 129 Jan 3-introduced in House; to Health & Family Services (H) HB 50 http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/17RS/HB50.htm Rep. Kenny Imes (R) Amend various parts of KRS Chapter 13A regarding regulations. Jan 3-introduced in House; to Licensing, Occupations, and Admin Regs (H) Feb 10-posted in committee Page 1 of 12 HB 63 http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/17RS/HB63.htm Rep. -

ELECTED OFFICIALS June 2021

ELECTED OFFICIALS June 2021 U.S. SENATORS Rand Paul (R) 1029 State St 270-782-8303 www.paul.senate.gov Bowling Green KY 42101 167 Russell Senate Office Bldg 202-224-4343 Washington, DC 20510 Mitch McConnell (R) 771 Corporate Dr Ste 108 859-224-8286 www.mcconnell.senate.gov Lexington KY 40503 317 Russell Senate Office Bldg 202-224-2541 Washington DC 20510 UNITED STATES CONGRESS (6th District) Andy Barr (R) 2709 Old Rosebud Rd Ste 100 859-219-1366 www.barr.house.gov Lexington KY 40509 1427 Longworth House Office Bldg 202-225-4706 Washington DC 20515 STATE OFFICES Governor Andy Beshear (D) 700 Capitol Ave Ste 100 502-564-2611 www.governor.ky.gov Frankfort KY 40601 Lt Governor Jacqueline Coleman (D) 700 Capitol Ave Ste 142 502-564-2611 www.governor.ky.gov Frankfort KY 40601 Secretary of State Michael Adams (R) 700 Capitol Ave Ste 152 502-564-3490 www.sos.ky.gov Frankfort KY 40601 Attorney General Daniel Cameron (R) 700 Capitol Ave Ste 118 502-696-5300 www.ag.ky.gov Frankfort KY 40601 Auditor of Public Mike Harmon (R) 209 St Clair St 502-564-5841 Accounts www.auditor.ky.gov Frankfort KY 40601 State Treasurer Allison Ball (R) 1050 US Highway 127 S Ste 100 502-564-4722 www.treasury.ky.gov Frankfort KY 40601 Comm of Agriculture Ryan Quarles (R) 105A Corporate Dr 502-573-0282 www.kyagr.ky.com Frankfort KY 40601 STATE SENATORS Legislative Message Line 800-372-7181 District 12 Alice Forgy Kerr (R) 702 Capitol Ave Annex 502-564-8100 [email protected] Frankfort KY 40601 District 13 Reginald Thomas (D) 702 Capitol Ave Annex 502-564-8100 [email protected] -

ENDORSED JULIE TENNYSON (D)—No Response U.S

Kentucky Right to Life 2018 GENERAL ELECTION PAC ALERT VOTE PRO-LIFE ON TUESDAY, NOV. 6TH KY SENATE * INDICATES “INCUMBENT” 2 *DANNY CARROLL (R)— ENDORSED JULIE TENNYSON (D)—no response U.S. HOUSE 4 ROBBY MILLS (R)—ENDORSED 1 *JAMES R. COMER (R)—ENDORSED *J. DORSEY RIDLEY (D)—no response 1 PAUL WALKER (D) 6 *C. B. EMBRY, JR. (R)—ENDORSED 2 *BRETT GUTHRIE (R)—ENDORSED CRYSTAL CHAPPELL (D)—no response 2 HANK LINDERMAN (D) 2 THOMAS LOECKEN (Ind) 8 MATT CASTLEN (R)—ENDORSED BOB GLENN (D)—some pro-life responses 10 *DENNIS PARRETT (D)—no response 12 *ALICE FORGY KERR (R)—ENDORSED PAULA SETSER-KISSICK (D)—no response 14 *JIMMY HIGDON (R)—ENDORSED STEPHANIE COMPTON (D)—no response 3 VICKIE GLISSON (R)—ENDORSED 3 *JOHN YARMUTH (D) - Strong pro-abortion position; 16 *MAX WISE (R)—ENDORSED former board member for Louisville Planned Parenthood; 100% lifetime rating by Planned Parenthood Action Fund. 18 SCOTT SHARP (R)—ENDORSED 3 GREGORY BOLES (Lib) *ROBIN WEBB (D)—no response 4 *THOMAS MASSIE (R)—RECOMMENDED 20 *PAUL HORNBACK (R)—ENDORSED 4 SETH HALL (D) DAVE SUETHOLZ (D)—no response 4 MIKE MOFFETT (Ind) 22 *TOM BUFORD (R)—ENDORSED 5 *HAROLD ROGERS (R)—ENDORSED CAROLYN DUPONT (D)—no response 5 KENNETH STEPP (D)—pro-life responses 24 *WIL SCHRODER (R)—ENDORSED RACHEL ROBERTS (D)—no response 26 *ERNIE HARRIS (R)—ENDORSED KAREN BERG (D)—no response JODY HURT (Ind)—pro-life responses 28 *RALPH ALVARADO (R)—ENDORSED DENISE GRAY (D)—no response 30 *BRANDON SMITH (R)—ENDORSED PAULA CLEMONS-COMBS (D)—no response 32 *MIKE WILSON (R)—ENDORSED JEANIE SMITH -

February 2018 Newsletter.Indd

464 Chenault Road | Frankfort, KY 40601 Phone: 502-695-4700 Fax: 502-695-5051 www.kychamber.com 464 Chenault Road | Frankfort, KY 40601 Phone: 502-695-4700 Fax: 502-695-5051 www.kychamber.com NEWSFEBRUARY 2018 KENTUCKY CHAMBER CHAIRMAN CRAFT “All In” on Tort Reform PLEDGES SUPPORT FOR Uncertainty and unlimited liability are the hallmark features of Kentucky’s “wild west” legal liability environment. While Leadership it may make for good movies, it does not make for a good business climate. That’s why we need tort reform. For most Kentucky businesses and health care providers, it isn’t a question of if they will face a lawsuit from the Institute powerful trial attorney bar, but when. for School The U.S. Chamber ranks Kentucky’s legal liability climate at 42nd, one of the worst in the nation, driving many businesses to operate elsewhere to avoid our sky- Principals high insurance costs and unlimited risks. Following a report about the Leadership Institute Make no mistake — the legal liability climate is an for School Principles to the Chamber’s Board of economic growth and development issue. Directors in early January, Kentucky Chamber Board Chairman Joe The current system creates challenges for Kentucky Kentucky should not be Craft, president of businesses and acts as a barrier to economic a playground for Alliance Resources, development, limiting the Commonwealth’s ability to made a generous offer attract and foster the next generation of employers, trial attorneys. to match any donation health care providers, and innovators. made to support — Matt Bevin, Governor principals in eastern Governor Bevin acknowledged that this is a major Kentucky.