Final Report of the Vermont Tax Structure Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAST Letter to the Congressional Military Family Caucus 7.21.20

July 21, 2020 Congressional Military Family Caucus Representative Sanford Bishop Representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers 2407 Rayburn HOB 1035 Longworth HOB Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 President Deborah Goldberg, MA Dear Rep. Bishop and Rep. McMorris Rodgers: Executive Committee Henry Beck, ME As we celebrate the 30th Anniversary of the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act David Damschen, UT Tim Eichenberg, NM (ADA), we can be proud of its positive impact on veterans with disabilities, while acknowledging Michael Frerichs, IL that there is much left to do. Dennis Milligan, AR Kelly Mitchell, IN The main purpose of the ADA is to provide people with disabilities equality of opportunity, full Shawn Wooden, CT participation in society, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency. But for more than two Executive Director decades after its passage, economic self-sufficiency was impossible for some. People with Shaun Snyder disabilities who need government benefits in order to live independently were blocked from saving 1201 Pennsylvania Ave, NW money. Without savings, economic self-sufficiency is unattainable. And without being able to Suite 800 fully participate in the economy, the other goals will not be fully realized. Washington, DC 20004 When the Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Act was passed into law in 2014, many www.NAST.org Americans with disabilities were empowered to save their own money to help pay for their disability expenses without fear of losing federal and state benefits. The Act was a meaningful step forward for people with disabilities. However, it came up short. After more than five years, and on the 30th birthday of the ADA, millions of Americans with disabilities, including veterans, still remain ineligible to open an ABLE account simply because they acquired their disability after they turned 26 years old. -

Annual Reports This Publication Was Airport, Burlington International

Cityof Burlington,Vermont Audited Financial Statements Year Ended June 30, 2012 2012 table of contents City Government ACKNOWLEDGMENTS City Organizational Chart . 2 Mayor’s Message . 3 Design/Production: Futura Design City Officials Appointed Printing: Queen City Printers Inc. by the Mayor . 6 Printed on PC Recycled Paper Vermont Legislators . 7 Photography: Photos by Patricia Braine ©2013 Mayors of Burlington . 7 SilverImagesVermont.com. Available for purchase to support Burlington Parks & City Council . 8 Recreation Scholarship Program. City Council Standing Committees . 9 Cover photos: Raychel Severence, Ted Olson, Carolyn City Departments & Office Hours . 10 Bates, Launie Kettler, Patricia Braine, Karen Pike. Important Dates . 11 Project Managment: Jennifer Kaulius, Mayor’s Office City Holidays . 11 This report can be made available in alternate formats for Board of School Commissioners . 12 persons with disabilities. City Commissioners . 13 This report also is available online at Regularly Scheduled www.burlingtonvt.gov. Commission Meetings . 18 Department Annual Reports This publication was Airport, Burlington International . 19 printed on paper certified Arts, Burlington City. 20 to the FSC® standard. Assessor, Office of the City . 22 It was manufactured using Attorney, Office of the City . 23 high solid inks containing Church Street Marketplace . 26 no VOCs and 100% Green-e® Certified Clerk/Treasurer, Office of the City . 28 Renewable Energy Code Enforcement . 30 through the purchase of Community and Economic Renewable Energy Development Office . 32 Credits (RECs). Electric Department . 36 Fire Department . 38 Housing Authority . 40 Human Resources Department. 41 Fletcher Free Library . 43 Parks & Recreation Department. 46 Planning & Zoning Department . 51 Police Department . 53 Public Works Department . 57 School District . -

State Treasurer

To: House Committee on Commerce and Economic Development Senate Committee on Economic Development, Housing and General Affairs From: Beth Pearce, State Treasurer Date: January 12, 2016 Re: Vermont Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Task Force Legislative Report, Pursuant to ACT No. 51, Title 33, CHAPTER 80. § 8004 of 2015 Overview During the 2015 legislative session, the General Assembly, in collaboration with the Office of the State Treasurer, Vermont stakeholders, State agencies and departments, and legislators, secured passage of Vermont's enabling legislation for the implementation of the federal ABLE Act. The Vermont Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Savings Program is intended to ease financial strains faced by individuals with disabilities by making federal tax-free savings accounts available to cover qualified expenses such as education, housing, and transportation. American families currently enjoy tax incentives to save for significant future expenses such as college, retirement, and other life events. The ABLE Act empowers individuals with disabilities and their families to save their own money in a 529A (or ABLE) account for the purpose of maintaining health and independence without jeopardizing the account holder’s federal benefits including Social Security and Medicaid.1 Vermont passed enabling Legislation (S.138) for a Vermont ABLE Savings Program in ACT 51 during the 2015 Legislative Session. The Governor signed Vermont’s ABLE legislation into law on June 3, 2015. The Office of the State Treasurer recommended addressing IRS issues prior to implementation to avoid potential administrative problems that could impact participants. In the interim, the Office of the State Treasurer has been engaged in monitoring and responding to the regulatory environment for state ABLE programs and in soliciting stakeholder input as charged under ACT 51. -

So Far, All Signs Point to the National Nuclear Renaissance Passing by New England

NUCLEAR OPTION Vermont Yankee, a nuclear power plant on the Connecticut River, is up for re-licensing, a process that in Vermont requires the Legislature’s approval. POWER POLITICS SO FAR, ALL SIGNS POINT TO THE NATIONAL NUCLEAR RENAISSANCE PASSING BY NEW ENGLAND. [ BY BARBARA MORAN ] n February 24, Randy Brock, a Republican state sena- friendly, and reliable and wants the plant to stay open. But a series of prob- tor in Vermont, did something he never expected to lems at Vermont Yankee forced his hand. “If their board of directors and do. He voted to close Vermont Yankee, the state’s its management had been thoroughly infiltrated by anti-nuclear activists,” only nuclear power plant. A longtime supporter he says, “they could not have done a better job destroying their own case.” of the plant, Brock did not want to vote this way. Vermonters – including the senator – were fed up with the way the plant He considers nuclear power safe, environmentally was being run, so he voted no. PRESS/ ASSOCIATED BY PHOTOGRAPH PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION STAFF GLOBE ENTERGY; 16 THE BOSTON GLOBE MAGAZINE MAY 9, 2010 POWER POLITICS The Vermont vote, coming just a week after President Barack Obama States since the Three Mile Island reactor accident in 1979 (several opened announced $8.33 billion in federal loan guarantees for companies building after the accident), in other countries – France in particular, and China – two new nuclear reactors in Georgia, would seem to show a New England nuclear power is increasingly common, and new technologies that create stuck in the no-nukes 1980s, out of step with the nuclear fever sweeping less waste and offer better containment have lowered the risk of environ- the rest of the country. -

Tuesday, February 14, 2017 Senator Mitch Mcconnell Senate Majority

Tuesday, February 14, 2017 Senator Mitch McConnell Senate Majority Leader 317 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Senator McConnell, Nearly 55 million workers across the country lack access to employer-sponsored retirement plans, and millions more fail to take full advantage of employer-supported plans. Without access to easy and affordable retirement savings options, far too many workers are on track to retire into poverty where they will depend on Social Security, state, and federal benefit programs for their most basic retirement needs. States across the country have been innovating to address this problem. We are writing to respectfully urge you to protect the rights of states and large municipalities to implement their own, unique approaches. Last week, two resolutions of disapproval (H.J. Res 66, H.J. Res 67) were introduced to repeal key Department of Labor (US DOL) rules. If passed, these resolutions would make it more difficult for states and municipalities to seek solutions to the growing retirement savings crisis. We ask that you support the role of states as policy innovators by voting “No” on H.J. Res 66 and H.J. Res 67. Thirty states and municipalities are in the process of implementing or exploring the establishment of state-facilitated, private-sector retirement programs. Eight states have passed legislation to allow individuals to save their own earnings for retirement (no employer funds are involved as these are not defined benefit plans). While most state and municipal plans will be governed by independent boards, the day-to-day investment management and recordkeeping would not be conducted by the state, but rather by private sector firms - the same financial institutions that currently provide retirement savings products. -

2020 Nasact Annual Conference

PROGRAM NASACT 2020 ANNUAL CONFERENCE August 24-28 | Virtual Training CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION Learning Objectives: Delivery Method: Group internet-based. All sessions include At the conclusion of the event, participants will be able to: Q&A opportunities. • Recount changes to the roles and responsibilities of state Attendance Requirements: In order to obtain CPE credit for auditors, state comptrollers and state treasurers as these this event, participants must submit attendance verification roles have evolved during the past year. codes provided during each session. • Identify and discuss new standards and rules from the government standards setting bodies and regulatory The National Association of State agencies. Auditors, Comptrollers and Treasurers is • Apply practical information learned through case studies registered with the National Association from peer offices and organizations. of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) • Discuss state government financial management as it as a sponsor of continuing professional relates to the broader, national fiscal outlook. education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance Level of Knowledge: Overview. of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding Education Prerequisite: No prerequisites required. registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: https://www. Advance Preparation: No advance preparation required. nasbaregistry.org/. CPE: 29.5 credits have been recommended for the conference. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Dear NASACT Members and Partners, It is my honor to welcome you to the 104th NASACT Annual Conference. I had hoped to welcome you to Vermont for this event, but the Covid-19 pandemic prevented that from happening. -

Refer to This List for Area Legislators and Candidates

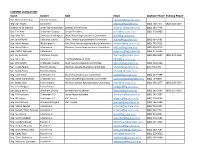

CURRENT LEGISLATORS Name District Role Email Daytime Phone Evening Phone Sen. Richard Westman Lamoille County [email protected] Rep. Dan Noyes Lamoille-2 [email protected] (802) 730-7171 (802) 644-2297 Speaker Mitzi Johnson Grand Isle-Chittenden Speaker of the House [email protected] (802) 363-4448 Sen. Tim Ashe Chittenden County Senate President [email protected] (802) 318-0903 Rep. Kitty Toll Caledona-Washington Chair, House Appropriations Committee [email protected] Sen. Jane Kitchel Caledonia County Chair, Senate Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 684-3482 Rep. Mary Hooper Washington-4 Vice Chair, House Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 793-9512 Rep. Marty Feltus Caledonia-4 Member, House Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 626-9516 Rep. Patrick Seymour Caledonia-4 [email protected] (802) 274-5000 Sen. Joe Benning Caledonia County [email protected] (802) 626-3600 (802) 274-1346 Rep. Matt Hill Lamoille 2 *NOT RUNNING IN 2020 [email protected] Sen. Phil Baruth Chittenden County Chair, Senate Education Committee [email protected] (802) 503-5266 Sen. Corey Parent Franklin County Member, Senate Education Committee [email protected] 802-370-0494 Sen. Randy Brock Franklin County [email protected] Rep. Kate Webb Chittenden 5-1 Chair, House Education Committee [email protected] (802) 233-7798 Rep. Dylan Giambatista Chittenden 8-2 House Leadership/Education Committee [email protected] (802) 734-8841 Sen. Bobby Starr Essex-Orleans Member, Senate Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 988-2877 (802) 309-3354 Sen. -

January 31, 2021 State Treasurer Beth Pearce's Report to The

Rep. Scott Campbell, St. Johnsbury VT 2021 Front Porch Forum updates, 1 of 4 January 31, 2021 State Treasurer Beth Pearce's report to the Legislature about the condition with the State's retirement pension system for our teachers and State employees arrived two weeks ago, and it's grim reading. It is also complicated. Vermont has three pension systems, one for public school Teachers, one for State Employees, and one for Municipal Employees. The Municipal system is funded locally; Teachers and State Employees systems are the responsibility of the State. (In addition, Teachers and Employees receive Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEBs), primarily health care — a separate but related obligation.) State Employees include all who receive a State of Vermont paycheck, except "exempt" employees. Exempts include statewide elected officials; agency and department heads, deputies, and executive assistants; and certain others. Members of the Legislature do not qualify for any pension system (though we can access a pre-tax savings plan). Teachers and Employees pension systems are Defined Benefit (DB), meaning the future benefit payout is calculated in advance and guaranteed; Teachers and Employees do make a fixed negotiated contribution from their paychecks, but the risk falls on the State to ensure funds are available when they retire. Exempts are eligible for an optional Defined Contribution (DC) plan, which means they may make a pre- tax contribution and the State will contribute a match; but the future benefit is not assured and the risk falls on the exempt employee. Vermont's pension crisis has been building for decades. In 2007/08, close to having it under control, the Legislature enacted a plan to fully retire the deficit by 2038. -

NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY the Electoral Success And

NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY The Electoral Success and Representation of Minorities: Different Cost of Voting Scenarios A Capstone Submitted to the University Honors Program In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Baccalaureate Degree With Honors Department Of Political Science By Shalisha Hill DeKalb, Illinois June 6, 2021 Hill 1 HONORS CAPSTONE ABSTRACT This research tests whether minorities are underrepresented in state legislatures due to restrictive state election laws that hinder voting. Some states like Oregon make it easier for citizens to vote and other states like Texas make it more difficult. The Cost of Voting Index (COVI) is a measurement of the electoral/institutional restrictiveness of each state and values are available for presidential election years from 1996 to 2020. Previous research has revealed that the amount of voting restrictions that citizens face makes it harder for them to vote (Li, Pomante Schraufnagel, 2018). What is less understood is whether restrictions hurt Blacks and Latinos running for statewide offices. This research will test whether the COVI can help predict voting margins, which in turn will reveal how successful minority candidates will be in states that are less restrictive or more restrictive. Broadly, the purpose of this research is to understand the electoral success of minorities and how the COVI helps to explain their success. Most specifically, the research question I examine is, does the restrictiveness of each state’s electoral/institutional climate help explain the relative underrepresentation of minorities in government? In other words, can the restrictiveness of state election laws help explain a lack of representation of Blacks and Latinos in elected offices? Hill 2 Introduction Aside from voter turnout, at either the aggregate or individual level, I look to examine the electoral success of minority candidates who run for public office. -

Governor-Elect Shumlin Appoints Beth Pearce As Vermont's Next State Treasurer

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 20, 2010 Contact: Alexandra MacLean, (802) 279-3560 Governor-Elect Shumlin Appoints Beth Pearce as Vermont’s Next State Treasurer Montpelier, Vt., - Governor-elect Shumlin announced today that Beth Pearce will be Vermont’s next State Treasurer. Beth is currently Vermont’s Deputy Treasurer and will assume the role of State Treasurer in January when Jeb Spaulding becomes the Secretary of Administration. “No one in Vermont is more qualified than Beth Pearce to succeed Jeb Spaulding as our state’s Treasurer,” said Shumlin. “Beth’s many years of experience in the Treasurer’s office, her enthusiasm for the job, and her passion for the state’s fiscal stability will serve Vermonters well.” Beth joined the Office of the Vermont State Treasurer on June 30, 2003, as Deputy Treasurer. In this capacity she has been responsible for a full range of operations including retirement administration of three state-wide systems (State, Teacher and Municipal), unclaimed property, accounting, budget, debt and capital financing, cash management, investment of short term funds in State custody and risk man- agement. Beth has more than 30 years of experience in government finance at both state and local levels. She served as Deputy Treasurer for Cash Management at the Massachusetts State Treasurer’s Office from 1999-2003. Prior to that, Beth served as Deputy Comptroller for the Town of Greenburgh, New York, and as the Accounting Manager and Financial Operations Manager for the Town of West Hartford, Connecticut. Previously, she served as a fiscal officer with the Massachusetts Department of Social Services and as a project director for the Massachusetts Executive Office of Human Services. -

Caledonia County Choose

2016 Gun Owners of Vermont Voter Guide CALEDONIA COUNTY CHOOSE Contest District Party Name On Ballot For President National Republican DONALD TRUMP: MIXED Vice President National Republican MIKE PENCE: STRONG PRO 2A For President National Libertarian GARY JOHNSON: STRONG PRO 2A Vice President National Libertarian WILLIAM F. WELD: ANTI-GUN For US Senate National United States Marijuana CRIS ERICSON For US Senate National Liberty Union PETE DIAMONDSTONE State Level Candidates Contest District Party Name On Ballot For Governor State Republican PHIL SCOTT For Lieutenant Governor State Republican RANDY BROCK Secretary of State State Democratic / Republican JIM CONDOS For Auditor of Accounts State Republican DAN FELICIANO For Attorney General State Republican DEBORAH 'DEB' BUCKNAM Local Level Candidates Vote For Is candidate Contest District Party Name On Ballot # Pro or Anti? For State Senate Caledonia STRONG PRO Republican JOE BENNING ONLY 1 (incumbent) Senate 2A Caledonia For State Senate MARIJUANA GALEN DIVELY III UNKNOWN Senate For State Senate Caledonia Democratic JANE KITCHEL ANTI-GUN (incumbent) Senate For State Representative MARCIA ROBINSON STRONG PRO Caledonia-1 Republican (incumbent) MARTEL 2A ONLY 1 ONLY 1 For State Representative Caledonia-2 Republican LAWRENCE W. HAMEL PRO 2A For State Representative STRONG PRO Caledonia-3 Republican JANSSEN WILLHOIT (incumbent) 2A ONLY 2 Updated 11/6/16 http://www.gunownersofvermont.org/wordpress/research-analysis/Candidates/Candidate_Reports.htm For State Representative Caledonia-3 Republican -

2018 NAST Treasury Management Training Symposium

2018 NAST Treasury Management Training Symposium June 5-8 | Buena Vista Palace | Lake Buena Vista, FL A decade ago, we set out to provide innovative analytic services that help state governments increase financial compliance and benefit their citizens. Today we find, save, or recover over half a billion dollars each year for dozens of government agencies and their citizens. www.verusfinancial.com | 1.855.NCLAIMU (855.625.2468) | general@verusfinancial.com A MESSAGE FROM NAST’S PRESIDENT I am pleased to welcome you to the 2018 National Association of State Treasurers (NAST) Treasury Management Training Symposium. For over 40 years NAST has provided advocacy, support and educational opportunities for State Treasurers, their staff, and members in non-treasury agencies that complete our affiliate networks. As an association of finance officers, we strive to advance the development and administration of sound fiscal policies, prudent management of state resources, and the ongoing support of financial wellness programs in our respective states. As our country faces a number of fiscal challenges such as aging infrastructure, rising levels of student debt, and a lack of retirement readiness and financial security, the Treasury Management Training Symposium provides a unique opportunity for our members and stakeholders to collaborate and learn from one another in solving these pressing issues. This year’s symposium offers training sessions on core functions and programs such as investing, managing pensions, overseeing state debt, the administration of unclaimed property, as well as outreach initiatives, such as administering ABLE plans, promoting financial literacy, and improving the affordability of post-secondary education. I would like to thank the entire NAST leadership team for their hard work and continued efforts to improve the organization and serve our membership.