Beyond Safe Land: Why Security of Land Tenure Is Crucial for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution and Nesting Density of the Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga

Ibis (2003), 145, 130–135 BlackwellDistribution Science, Ltd and nesting density of the Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi on Mindanao Island, Philippines: what do we know after 100 years? GLEN LOVELL L. BUESER,1 KHARINA G. BUESER,1 DONALD S. AFAN,1 DENNIS I. SALVADOR,1 JAMES W. GRIER,1,2* ROBERT S. KENNEDY3 & HECTOR C. MIRANDA, JR1,4 1Philippine Eagle Foundation, VAL Learning Village, Ruby Street, Marfori Heights Subd., Davao City 8000 Philippines 2Department of Biological Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58105, USA 3Maria Mitchell Association, 4 Vestal Street, Nantucket, MA 02554, USA 4University of the Philippines Mindanao, Bago Oshiro, Davao City 8000 Philippines The Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi, first discovered in 1896, is one of the world’s most endangered eagles. It has been reported primarily from only four main islands of the Philippine archipelago. We have studied it extensively for the past three decades. Using data from 1991 to 1998 as best representing the current status of the species on the island of Mindanao, we estimated the mean nearest-neighbour distances between breeding pairs, with remarkably little variation, to be 12.74 km (n = 13 nests plus six pairs without located nests, se = ±0.86 km, range = 8.3–17.5 km). Forest cover within circular plots based on nearest-neighbour pairs, in conjunction with estimates of remaining suitable forest habitat (approximately 14 000 km2), yield estimates of the maximum number of breeding pairs on Mindanao ranging from 82 to 233, depending on how the forest cover is factored into the estimates. The Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi is a large insufficient or unreliable data, and inadequately forest raptor considered to be one of the three reported methods. -

LAYOUT for 2UPS.Pmd

July-SeptemberJuly-September 20072007 PHILJA NEWS DICIA JU L EME CO E A R U IN C P R P A U T P D S I E L M I H Y P R S E S U S E P P E U N R N I I E B P P M P I L P E B AN L I ATAS AT BAY I C I C L H I O P O H U R E F T HE P T O F T H July to September 2007 Volume IX, Issue No. 35 EE xx cc ee ll ll ee nn cc ee ii nn tt hh ee JJ uu dd ii cc ii aa rr yy 2 PHILJA NEWS PHILJAPHILJA BulletinBulletin REGULAR ACADEMIC A. NEW APPOINTMENTS PROGRAMS REGIONAL TRIAL COURTS CONTINUING LEGAL EDUCATION PROGRAM REGION I FOR COURT ATTORNEYS Hon. Jennifer A. Pilar RTC Br. 32, Agoo, La Union The Continuing Legal Education Program for Court Attorneys is a two-day program which highlights REGION IV on the topics of Agrarian Reform, Updates on Labor Hon. Ramiro R. Geronimo Law, Consitutional Law and Family Law, and RTC Br. 81, Romblon, Romblon Review of Decisions and Resolutions of the Civil Hon. Honorio E. Guanlao, Jr. Service Commission, other Quasi-judicial Agencies RTC Br. 29, San Pablo City, Laguna and the Ombudsman. The program for the Hon. Albert A. Kalalo Cagayan De Oro Court of Appeals Attorneys was RTC Br. 4, Batangas City held on July 10 to 11, 2007, at Dynasty Court Hotel, Hon. -

Newletter No30 AUG 2017 Draft 5

DISPATCH CEBU ISSUE NO. 30 AUGUST 2017 Air Juan holds press launch, adds 2 new routes from CEB Departure Flight Crew of Cebu-Maasin Local airline Air Juan (AO) held a press launch at Mactan Cebu International Airport last August 1. Air Juan President Mr. John Gutierrez, Marketing Head Mr. Paolo Misa and seaplane pilot Mr. Mark Griffin answered questions from the media, together with GMCAC Chief Commercial Advisor Mr. Ravi Saravu. Air Juan does not compete with the bigger airlines, rather it connects the smaller islands. They want to be known for their seaplanes, which they also plan to operate in Cebu soon. Cake Cutting Ceremony Q&A with Press L-R: Air Juan Seaplane Pilot Mr. Mark Griffin, Air Juan President Mr. John Gutierrez, GMCAC Chief Commercial Advisor Mr. Ravi Saravu, Air Juan Marketing Head Mr. Paolo Misa. The press event coincided with the maiden flight of its new route from Cebu to Maasin, Leyte. Air Juan also launched Cebu to Sipalay in Negros on August 3. They now operate 6 routes from Cebu, including the tourist destinations of Tagbilaran (Bohol), Siquijor, Bantayan Island and Biliran. Departure Water Cannon Salute of 1st Commercial Flight (Cebu-Caticlan) PAL introduces new Q400 NG aircraft Mactan Cebu International Airport welcomed the arrival of Philippine Airlines’ new Bombardier Q400 Next Generation aircraft last August 1. PAL Express President Mr. Bonifacio Sam and Bombardier Director for Asia Pacific Sales Mr. Aman Kochher, among other VIP guests and media, graced the sendoff ceremony of the aircraft’s 1st commercial flight bound for Caticlan (Boracay). -

10. Survey of Timber Entrepreneurs in Region 8 and Cebu, the Philippines: Preliminary Findings

10. SURVEY OF TIMBER ENTREPRENEURS IN REGION 8 AND CEBU, THE PHILIPPINES: PRELIMINARY FINDINGS Janet Cedamon, Edwin Cedamon, Steve Harrison, Nestor Gregorio, Eduardo Mangaoang and John Herbohn The lack of information by smallholders about market opportunities and the timber product requirements of buyers may be a major impediment to development of formal or regular timber markets. Anecdotal evidence suggests that growers fare poorly in terms of prices obtained under current arrangements, with consequent inadequate market signals to encourage tree planting. This paper presents preliminary results of a survey conducted to investigate the status and prospects of timber enterprises in Leyte and Cebu in the Philippines. The operators were interviewed in 51 timber enterprises, of which 34 are registered with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. The majority (74%) of the enterprises were engaged in retailing sawn timber. About 58% obtained some or 61% obtained timber from timber merchants while 33% directly from tree growers. Respondents identified proper plantation management as one of the measures to improve the quality of timber from smallholder tree farmers. The present forest policies, support from the government, low quality of timber and insufficient supply of timber were nominated as problems experienced by the respondents. INTRODUCTION A substantial number of smallholders on Leyte Island in the Philippines have small-scale tree plantings on the land they own or cultivate (Cedamon and Emtage 2005). Emtage (2004) explained that there are clear opportunities for communities and smallholder tree farmers to supply timber products into local markets, if they can meet bureaucratic requirements for timber harvesting and transport. -

Dear Friends

Donor Impact Report Gawad Kalinga: Philippine Relief and Recovery Efforts On November 8, 2013, Typhoon Haiyan struck the Philippines and carved a path of devastation across Southeast Asia. The storm, known in the affected region as Typhoon Yolanda affected 16 million people in the Philippines. This includes the displacement of 4.1 million people, the damage or destruction of 1.1 million homes, and 6,155 recorded deaths. In the days following the storm, many members of our donor network asked if Focusing Philanthropy could suggest an effective way to contribute to relief and recovery projects, In response, we concentrated our full team’s efforts on identifying and intensively evaluating candidates for donor support. On November 14, 2013 we announced our recommendation of Gawad Kalinga for those who wished to support the immediate relief and long-term rebuilding efforts in the Philippines. Read more about our diligence process and reasons for recommending Gawad Kalinga. Since then, Focusing Philanthropy’s network of generous donors has contributed $34,600 towards Gawad Kalinga’s relief and recovery efforts, with the majority of these funds raised and granted to Gawad Kalinga within the first few weeks following the storm. This report summarizes Gawad Kalinga’s activities and their impacts in the four months since Typhoon Haiyan. Immediate Relief Efforts Gawad Kalinga was actively involved in regional relief efforts even before Typhoon Haiyan. On October 15, 2013 a magnitude 7.2 earthquake struck the Bohol province, an island located in Central Visayas, Philippines. It was the deadliest earthquake in the Philippines in 23 years with 222 reported deaths, nearly 1,000 injured, and damage to more than 73,000 structures. -

Philippines 13

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Philippines North Luzon p119 Manila #_ Around Manila p101 p52 Southeast Mindoro Luzon p198 p171 Cebu & Boracay & Eastern Western Visayas Palawan Visayas p283 p383 p217 Mindanao p348 Paul Harding, Greg Bloom, Celeste Brash, Michael Grosberg, Iain Stewart PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome MANILA . 52 Subic Bay & Olongapo . 115 to the Philippines . 6 Mt Pinatubo Region . 117 The Philippines Map . 8 AROUND MANILA . 101 The Philippines’ Top 15 . 10 NORTH LUZON . 119 Need to Know . 18 Corregidor . 103 Zambales Coast . 122 First Time Philippines . 20 South of Manila . 103 Tagaytay & Lake Taal . 103 Southern What’s New . 22 Zambales Coast . 122 Taal . 107 If You Like . 23 Iba & Botolan . 123 Batangas . 108 Month by Month . 25 North of Iba . 124 Anilao . 109 Itineraries . 28 Lingayen Gulf . 124 Mt Banahaw . 110 Diving in the Bolinao & Patar Beach . 124 Pagsanjan . 110 Philippines . 33 Hundred Islands Outdoor Activities . 39 Lucban . 111 National Park . 124 Eat & Drink Lucena . 112 San Juan (La Union) . 125 Like a Local . .. 44 North of Manila . 112 Ilocos . 127 Regions at a Glance . 49 Angeles & Clark Airport . 113 Vigan . 127 ALENA OZEROVA/SHUTTERSTOCK © OZEROVA/SHUTTERSTOCK ALENA © SHANTI HESSE/SHUTTERSTOCK EL NIDO P401 TOM COCKREM/GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES COCKREM/GETTY TOM STREET FOOD, PUERTO PRINCESA P385 Contents Laoag . 132 San Jose . 164 Mt Isarog Pagudpud & Around . 134 Northern Sierra Madre National Park . 177 The Cordillera . 135 Natural Park . 164 Caramoan Peninsula . 177 Baguio . 137 Tuguegarao . 165 Tabaco . 180 Kabayan . 144 Santa Ana . 166 Legazpi . 180 Mt Pulag National Park . 146 Batanes Islands . 166 Around Legazpi . -

COMMUNITY-BASED MARINE SANCTUARIES in the PHILIPPINES:A REPORT on FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSIONS

COMMUNITY-BASED MARINE SANCTUARIES in the PHILIPPINES:A REPORT on FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSIONS Brian Crawford, Miriam Balgos and Cesario R. Pagdilao June 2000 Coastal Resources Center Philippine Council for Aquatic and University of Rhode Island Marine Research and Development 1. Introduction 1.1 Project Overview The Coastal Resources Center of the University of Rhode Island (CRC) was awarded a three-year grant in September 1999, from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation to foster marine conservation in Indonesia. The overall goal of the project is to build local capacity in North Sulawesi Province to establish and successfully implement community- based marine sanctuaries. The project builds on previous and on-going CRC field activities in North Sulawesi supported by the USAID Coastal Resources Management Project, locally known as Proyek Pesisir. While the primary emphasis of the project is on Indonesia, it includes a significant Philippine component in the first year. The project objectives are to: • Document methodologies and develop materials for use in widespread adaptation of community-based marine sanctuary approaches to specific site conditions • Build capacity of local institutions in North Sulawesi to replicate models of successful community-based marine sanctuaries by developing human resource capacity and providing supporting resource materials • Replicate small-scale community-based marine sanctuaries in selected North Sulawesi communities through on-going programs of local institutions Activities in the first year of the project are focusing on documenting the limited Indonesia experience and the more than two decades of Philippine experience in establishing and replicating community-based marine sanctuaries. The Philippine experience is highly relevant to Indonesia for several reasons. -

Establishing the Power Plant Contracts for the Leyte Geothermal Power Project

Javellanaet al. ESTABLISHING THE POWER PLANT CONTRACTS FOR THE LEYTE GEOTHERMAL POWER PROJECT P Javellana', B F M Dolor', M A Medado', M V de Jesus'. P R National Oil Company Energy Development Corporation, Manila, Philippines Morrison Ltd, Auckland. New Zealand KEYWORDS form, and in the Philippines, the conversion plant and the electricity market had both been the responsibility of NAPOCOR Figure Geothermal. Power Plant, Contracts. BOT, BOO illustrates this ABSTRACT This paper describes the process whereby PNOC-EDC, as resource developer and host utility, established a number of Build, Operate, Transfer (BOT) contracts for the power plants involved in the Leyte Geothermal Power Project. It the project itself and PNOC-EDC NAPOCOR describes some of the issues involved in selecting the strategy for establishing the contracts The bidding, evaluation and award processes are outlined and a number of lessons are drawn from the 1 Geothermal in Philippine experience gained, these lessons being of significance both hosts and prospective private sector developers. It concludes that the establishment of the contracts has been well executed and For the agreed development at Leyte, the power plant component emphasises that maintaining a very short timetable for bidding is a would be undertaken by However, the capital definite advantage. investment required (initially estimated as being of the order of US$ 700 million in addition the resource and developments) BACKGROUND was much to be undertaken on a self basis, and it was therefore decided to seek external participation by private sector Initial surface exploration of the Leyte geothermal resources power plant developerdoperators. commenced in 1972, and the Tongonan geothermal project came on line in 1983, using the lower Mahiao and Sambaloran sectors of In the case of a private sector involvement in the power plant, the the Mahiao reservoir. -

Cebgo Kicks Off MBT Flight

DISPATCH CEBU ISSUE NO. 30 AUGUST 2017 Departure Water Cannon Salute Cebgo celebrated its maiden flight to Masbate (MBT) last July 26. The first passenger to check in was awarded a round trip ticket to Cebgo kicks off Masbate. The aircraft was given a water cannon salute upon its MBT flight departure. Cebu Pacific now has 29 domestic destinations from Cebu. Awarding of 1st Passenger to Check In Departure Leis and Tokens L-R: GMCAC Head for Terminal Operations Ms. Nenette Castillon, Cebu Pacific Cebu Station Head Mr. Nicanor Camcam, 1st passenger to check in Mr. Amiel Maglente, Cebu Pacific Area Head Mr. Johnny Yap. Departure Water Cannon Salute of 1st Commercial Flight (Cebu-Caticlan) PAL introduces new Q400 NG aircraft Mactan Cebu International Airport welcomed the arrival of Philippine Airlines’ new Bombardier Q400 Next Generation aircraft last August 1. PAL Express President Mr. Bonifacio Sam and Bombardier Director for Asia Pacific Sales Mr. Aman Kochher, among other VIP guests and media, graced the sendoff ceremony of the aircraft’s 1st commercial flight bound for Caticlan (Boracay). The aircraft is the 1st delivery of 12 orders, and is the world's 1st dual class, 86-seat Q400 aircraft. Ribbon Cutting Ceremony Message from Mr. Bonifacio Sam, PALEX President GMCAC Airline Marketing Head Aines Librodo; Mr. Aman Kochher, Director Sales – Asia Pacific, Bombardier Inc.; Mr. Bonifacio Sam, PALEX President; Marianne Raymundo, Philippine Airlines SVP & Chief Finance Officer; Sylvia Domingo, Philippine Airlines, VP Marketing; Honorable Marcial Ycong, Vice Mayor Lapu lapu City; H.E. John Holmes, Canadian Ambassador; Atty. Siegfred Mison, Philippine Airlines, SVP Legal Counsel; Rob Burdekin, Regional Director Customer Services, Bombardier Inc. -

The Philippines Illustrated

The Philippines Illustrated A Visitors Guide & Fact Book By Graham Winter of www.philippineholiday.com Fig.1 & Fig 2. Apulit Island Beach, Palawan All photographs were taken by & are the property of the Author Images of Flower Island, Kubo Sa Dagat, Pandan Island & Fantasy Place supplied courtesy of the owners. CHAPTERS 1) History of The Philippines 2) Fast Facts: Politics & Political Parties Economy Trade & Business General Facts Tourist Information Social Statistics Population & People 3) Guide to the Regions 4) Cities Guide 5) Destinations Guide 6) Guide to The Best Tours 7) Hotels, accommodation & where to stay 8) Philippines Scuba Diving & Snorkelling. PADI Diving Courses 9) Art & Artists, Cultural Life & Museums 10) What to See, What to Do, Festival Calendar Shopping 11) Bars & Restaurants Guide. Filipino Cuisine Guide 12) Getting there & getting around 13) Guide to Girls 14) Scams, Cons & Rip-Offs 15) How to avoid petty crime 16) How to stay healthy. How to stay sane 17) Do’s & Don’ts 18) How to Get a Free Holiday 19) Essential items to bring with you. Advice to British Passport Holders 20) Volcanoes, Earthquakes, Disasters & The Dona Paz Incident 21) Residency, Retirement, Working & Doing Business, Property 22) Terrorism & Crime 23) Links 24) English-Tagalog, Language Guide. Native Languages & #s of speakers 25) Final Thoughts Appendices Listings: a) Govt.Departments. Who runs the country? b) 1630 hotels in the Philippines c) Universities d) Radio Stations e) Bus Companies f) Information on the Philippines Travel Tax g) Ferries information and schedules. Chapter 1) History of The Philippines The inhabitants are thought to have migrated to the Philippines from Borneo, Sumatra & Malaya 30,000 years ago. -

Supplementary Document 6: Typhoon Yolanda-Affected Areas and Areas Covered by the Kalahi– Cidss National Community-Driven Development Project

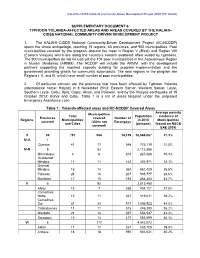

KALAHI–CIDSS National Community-Driven Development Project (RRP PHI 46420) SUPPLEMENTARY DOCUMENT 6: TYPHOON YOLANDA-AFFECTED AREAS AND AREAS COVERED BY THE KALAHI– CIDSS NATIONAL COMMUNITY-DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 1. The KALAHI–CIDDS National Community-Driven Development Project (KC-NCDDP) spans the whole archipelago, reaching 15 regions, 63 provinces, and 900 municipalities. Poor municipalities covered by the program abound the most in Region V (Bicol) and Region VIII (Eastern Visayas) which are along the country’s eastern seaboard often visited by typhoons. The 900 municipalities do not include yet the 104 poor municipalities in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). The NCDDP will include the ARMM, with the development partners supporting the required capacity building for program implementation and the government providing grants for community subprojects. The new regions in the program are Regions I, II, and III, which have small number of poor municipalities. 2. Of particular concern are the provinces that have been affected by Typhoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) in 8 November 2013: Eastern Samar, Western Samar, Leyte, Southern Leyte, Cebu, Iloilo, Capiz, Aklan, and Palawan, and by the Visayas earthquake of 15 October 2013: Bohol and Cebu. Table 1 is a list of areas targeted under the proposed Emergency Assistance Loan. Table 1: Yolanda-affected areas and KC-NCDDP Covered Areas Average poverty Municipalities Total Population incidence of Provinces covered Number of Regions Municipalities in 2010 Municipalities -

Occs and Bccs with Microsoft Office 365 Accounts1

List of OCCs and BCCs with Microsoft Office 365 Accounts1 COURT/STATION ACCOUNT TYPE EMAIL ADDRESS RTC OCC Caloocan City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Caloocan City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Las Pinas City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Las Pinas City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Makati City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Makati City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Malabon City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Malabon City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Mandaluyong City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Mandaluyong City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Manila City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Manila City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Marikina City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Marikina City OCC [email protected] 1 to search for a court or email address, just click CTRL + F and key in your search word/s RTC OCC Muntinlupa City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Muntinlupa City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Navotas City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Navotas City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Paranaque City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Paranaque City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Pasay City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Pasay City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Pasig City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Pasig City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Quezon City OCC [email protected] METC OCC