Innovative Design of Early Phase Clinical Trials in Radiation Oncology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combination of Cabazitaxel and Plicamycin Induces Cell Death in Drug Resistant B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Clinical and Translational Science Institute Centers 9-1-2018 Combination of cabazitaxel and plicamycin induces cell death in drug resistant B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia Rajesh R. Nair West Virginia University Debbie Piktel West Virginia University Werner J. Geldenhuys West Virginia University Laura F. Gibson West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/ctsi Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Digital Commons Citation Nair, Rajesh R.; Piktel, Debbie; Geldenhuys, Werner J.; and Gibson, Laura F., "Combination of cabazitaxel and plicamycin induces cell death in drug resistant B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia" (2018). Clinical and Translational Science Institute. 34. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/ctsi/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centers at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Clinical and Translational Science Institute by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Leuk Res Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2019 September 01. Published in final edited form as: Leuk Res. 2018 September ; 72: 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2018.08.002. Combination of cabazitaxel and plicamycin induces cell death in drug resistant B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia Rajesh R. Naira, Debbie Piktelb, Werner J. Geldenhuysc, -

PEMD-91-12BR Off-Label Drugs: Initial Results of a National Survey

11 1; -- __...._-----. ^.-- ______ -..._._ _.__ - _........ - t Ji Jo United States General Accounting Office Washington, D.C. 20648 Program Evaluation and Methodology Division B-242851 February 25,199l The Honorable Edward M. Kennedy Chairman, Committee on Labor and Human Resources United States Senate Dear Mr. Chairman: In September 1989, you asked us to conduct a study on reimbursement denials by health insurers for off-label drug use. As you know, the Food and Drug Administration designates the specific clinical indications for which a drug has been proven effective on a label insert for each approved drug, “Off-label” drug use occurs when physicians prescribe a drug for clinical indications other than those listed on the label. In response to your request, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of oncologists to determine: . the prevalence of off-label use of anticancer drugs by oncologists and how use varies by clinical, demographic, and geographic factors; l the extent to which third-party payers (for example, Medicare intermediaries, private health insurers) are denying payment for such use; and l whether the policies of third-party payers are influencing the treatment of cancer patients. We randomly selected 1,470 members of the American Society of Clinical Oncologists and sent them our survey in March 1990. The sam- pling was structured to ensure that our results would be generalizable both to the nation and to the 11 states with the largest number of oncologists. Our response rate was 56 percent, and a comparison of respondents to nonrespondents shows no noteworthy differences between the two groups. -

Mitomycin C: Indications for Use and Safe Practice in Ophthalmology Published by American Society of Ophthalmic Registered Nurses

Mitomycin C: Indications for Use and Safe Practice in Ophthalmology Published by American Society of Ophthalmic Registered Nurses Editor Susan Clouser, RN, MSN, CRNO American Society of Ophthalmic Registered Nurses 655 Beach Street, San Francisco, CA 94109 1 This publication includes independent authors’ guidelines for the safe use and handling of mitomycin C in ophthalmic practices. Readers should use these guidelines as a resource only. These guidelines should never take precedence over manufacturers’ recommended practices, facilities policies and procedures, or compliance with federal regulations. Information in this publication may assist facilities in developing policies and procedures specifc to their needs and practice environment. American Society of Ophthalmic Registered Nurses For questions regarding content or association issues contact ASORN at [email protected] or 1.415.561.8513. Copyright © 2011 by American Society of Ophthalmic Registered Nurses American Society of Ophthalmic Registered Nurses has the exclusive rights to reproduce this work, to prepare derivative works from this work, to publicly distribute this work, to publicly perform this work and to publicly display this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of American Society of Ophthalmic Registered Nurses. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The development of this educational resource would not have been possible without the knowledge and expertise of the ophthalmologists and ophthalmic registered nurses who wrote the content and the subsequent reviewers who provided valuable input. -

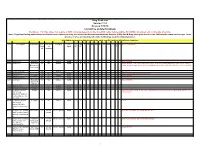

Drug Code List Version 11.4 Revised 5/18/18 List Will Be Updated Routinely

Drug Code List Version 11.4 Revised 5/18/18 List will be updated routinely Disclaimer: For drug codes that require an NDC, coverage depends on the drug NDC status (rebate eligible, Non-DESI, non-termed, etc) on the date of service. Note: Physician/Facility-administered medications are reimbursed using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Part B Drug pricing file found on the CMS website--www.cms.hhs.gov. In the absence of a fee, pricing may reflect the methodolgy used for retail pharmacies. Highlights represent updated material for each specific revision of the Drug Code List. Code Description Brand Name NDC NDC unit Category Service AC CAH P NP MW MH HS PO OPH HI IDT DC Special Instructions Requir of Limits OP OP F ed measure 90281 human ig, im Gamastan Yes ML Antisera NONE X X X X Closed 3/31/13. 90283 human ig, iv Gamimune, Yes ML Antisera NONE X X X X Closed 3/31/13. Cost invoice required with claim. Restricted to ICD-9 diagnoses codes 204.10 - 204.12, Flebogamma, 279.02, 279.04, 279.06, 279.12, 287.31, and 446.1, and must be included on claim form, effective 10/1/09. Gammagard 90287 botulinum antitoxin N/A Antisera Not Covered 90288 botulism ig, iv No ML NONE X X X X Requires documentation and medical review 90291 cmv ig, iv Cytogam Yes ML Antisera NONE X X X X Closed 3/31/13. 90296 diphtheria antitoxin No ML NONE X X X X 90371 hep b ig, im Bayhep B, Yes ML Antisera NONE X X X X Closed 3/31/13. -

How to Manage Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia

Leukemia (2012) 26, 1743 -- 1751 & 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/12 www.nature.com/leu HOW TO MANAGEy How to manage acute promyelocytic leukemia J-Q Mi, J-M Li, Z-X Shen, S-J Chen and Z Chen Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a unique subtype of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The prognosis of APL is changing, from the worst among AML as it used to be, to currently the best. The application of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) to the induction therapy of APL decreases the mortality of newly diagnosed patients, thereby significantly improving the response rate. Therefore, ATRA combined with anthracycline-based chemotherapy has been widely accepted and used as a classic treatment. It has been demonstrated that high doses of cytarabine have a good effect on the prevention of relapse for high-risk patients. However, as the indications of arsenic trioxide (ATO) for APL are being extended from the original relapse treatment to the first-line treatment of de novo APL, we find that the regimen of ATRA, combined with ATO, seems to be a new treatment option because of their targeting mechanisms, milder toxicities and improvements of long-term outcomes; this combination may become a potentially curable treatment modality for APL. We discuss the therapeutic strategies for APL, particularly the novel approaches to newly diagnosed patients and the handling of side effects of treatment and relapse treatment, so as to ensure each newly diagnosed patient of APL the most timely and best treatment. Leukemia (2012) 26, 1743--1751; doi:10.1038/leu.2012.57 Keywords: acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL); all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA); arsenic trioxide (ATO) INTRODUCTION In this review, we introduce the therapeutic strategies of APL, Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a distinct subtype of acute including the treatment of newly diagnosed and relapsed myeloid leukemia (AML) characterized by its abnormal promye- patients, as well as the ways to deal with the side effects. -

DRUG NAME: Thioguanine

Thioguanine DRUG NAME: Thioguanine SYNONYM(S): 2-amino-6-mercaptopurine,1 6-TG, TG COMMON TRADE NAME(S): LANVIS® CLASSIFICATION: antimetabolite, cytotoxic2 Special pediatric considerations are noted when applicable, otherwise adult provisions apply. MECHANISM OF ACTION: Thioguanine is a purine antagonist.1 It is a pro-drug that is converted intracellullarly directly to thioguanine monophosphate3 (also called 6-thioguanylic acid)4 (TGMP) by the enzyme hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HGPRT). TGMP is further converted to the di- and triphosphates, thioguanosine diphosphate (TGDP) and thioguanosine triphosphate (TGTP).5 The cytotoxic effect of thioguanine is a result of the incorporation of these nucleotides into DNA. Thioguanine has some immunosuppressive activity.1 Thioguanine is specific for the S phase of the cell cycle.6 PHARMACOKINETICS: Oral Absorption • incomplete and variable (14-46%)7 • preferably taken on an empty stomach8; may be taken with food if needed • children9: <20% Distribution crosses the placenta10 cross blood brain barrier? negligible11 volume of distribution12 148 mL/kg plasma protein binding no information found Metabolism hepatic10 activation by4: • hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HGPRT) elimination by4: • guanase to 6-thioxanthine • thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) to 2-amino-6-methyl thiopurine active metabolites3,4 thiopurine nucleotides inactive metabolites4 6-thioxanthine, 2-amino-6-methyl thiopurine Excretion renal excretion12; initially intact drug, then metabolites urine12 -

Severe Myelotoxicity Associated with Thiopurine S-Methyltransferase*3A

Case Report DOI: 10.4274/tjh.2013.0082 Severe Myelotoxicity Associated with Thiopurine S-Methyltransferase*3A/*3C Polymorphisms in a Patient with Pediatric Leukemia and the Effect of Steroid Therapy Pediatrik Bir Lösemi Olgusunda Tiyopurin S-Metiltransferaz *3A/*3C Polimorfizmi ile İlişkili Ağır Miyelotoksisite-Steroid Tedavisinin Etkisi Burcu Fatma Belen1, Türkiz Gürsel1, Nalan Akyürek2, Meryem Albayrak3, Zühre Kaya1, Ülker Koçak1 1Gazi University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pediatric Hematology, Ankara, Turkey 2Gazi University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pathology, Ankara, Turkey 3Kırıkkale University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pediatric Hematology, Ankara, Turkey Abstract: Myelosuppression is a serious complication during treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and the duration of myelosuppression is affected by underlying bone marrow failure syndromes and drug pharmacogenetics caused by genetic polymorphisms. Mutations in the thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) gene causing excessive myelosuppression during 6-mercaptopurine (MP) therapy may cause excessive bone marrow toxicity. We report the case of a 15-year-old girl with T-ALL who developed severe pancytopenia during consolidation and maintenance therapy despite reduction of the dose of MP to 5% of the standard dose. Prednisolone therapy produced a remarkable but transient bone marrow recovery. Analysis of common TPMT polymorphisms revealed TPMT *3A/*3C. Key Words: Myelosuppression, Thiopurine S-methyl transferase, Acute leukemia Özet: Miyelosupresyon, -

List of Drugs Not Repackaged by Safecor Health

Drugs Not Repackaged by Safecor Health The following tables list specific medications that are not repackaged by Safecor Health due to regulatory restrictions or specific manufacturer requirements. The items not repackaged are alphabetically listed below, both by brand name (table 1) and generic name (table 2). Please note: Safecor Health cannot repackage any beta lactam antibiotics (such as penicillins, amoxicillin and cephalosporins) or potent chemotherapeutic agents. Also, due to FDA restrictions, we cannot repackage half- or quarter-tabs, compounded or diluted drugs, powders, and ointments or creams. Safecor Health can repackage most hazardous drugs on the NIOSH list. Contact us for a complete list of hazardous drugs repackaged by Safecor Health. Table 1. Do Not Repackage Drugs Sorted Alphabetically by Brand Name Brand Name(s) Generic Name(s) Reason Item Cannot Be Repackaged Adrucil Fluorouracil Potent chemotherapy agent Aspirin and Extended-Release Specific manufacturer recommendations for very Aggrenox Dipyridamole limited expiration dating Albenza Albendazole Cost per dose prohibitive Alkeran Melphalan Potent chemotherapy agent Augmentin Amoxicillin and Clavulanate Potassium Safecor Health does not repackage this drug class Manufacturer states, "dispense in original container," Belsomra Suvorexant on the drug label Manufacturer states, "dispense in original container," Biktarvy Bictegravir, Emtricitabine and Tenofovir Alafenamide on the drug label Bion Tears Dextran, Hypromellose Ophthalmic Drops Sterile and unpreserved CeeNU Lomustine -

Immunomodulators

Fact Sheet News from the IBD Help Center IMMUNOMODULATORS Medical treatment for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis has two main goals: achieving remission (control or resolution of inflammation leading to symptom resolution with healing of the inflamed tissue) and then maintaining remission. To accomplish these goals, treatment is aimed at controlling the ongoing inflammation in the intestine—the cause of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) symptoms. As the name implies, immunomodulators modify the activity of the immune system, in turn, decreasing the inflammatory response. Immunomodulators are most often used in organ transplantation to prevent rejection of the new organ as well as in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Since the late 1960s, they have also been used to treat people with IBD, where the normal regulation of the immune system is affected. Immunomodulators, by themselves or with another agent, may be appropriate in the following treatment situations: • Nonresponse or intolerance to aminosalicylates, antibiotics, or corticosteroids • Steroid-dependent disease or frequent need for steroids • Perianal (around the anus) disease that does not respond to antibiotics • Fistulas (abnormal channels between two loops of intestine, or between the intestine and another structure—such as the skin) • To bolster or optimize the effect of a biologic drug and prevent the development of resistance to biologic drugs • To prevent recurrence after surgery Because it can take up to three to six months to see an improvement in symptoms with immunomodulators, steroids may be started at the same time to produce a faster response. Lower doses of the steroid may be utilized in some cases, producing fewer side effects. -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

Identification of Inhibitors of Ovarian Cancer Stem-Like Cells by High-Throughput Screening Roman Mezencev, Lijuan Wang and John F Mcdonald*

Mezencev et al. Journal of Ovarian Research 2012, 5:30 http://www.ovarianresearch.com/content/5/1/30 RESEARCH Open Access Identification of inhibitors of ovarian cancer stem-like cells by high-throughput screening Roman Mezencev, Lijuan Wang and John F McDonald* Abstract Background: Ovarian cancer stem cells are characterized by self-renewal capacity, ability to differentiate into distinct lineages, as well as higher invasiveness and resistance to many anticancer agents. Since they may be responsible for the recurrence of ovarian cancer after initial response to chemotherapy, development of new therapies targeting this special cellular subpopulation embedded within bulk ovarian cancers is warranted. Methods: A high-throughput screening (HTS) campaign was performed with 825 compounds from the Mechanistic Set chemical library [Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP)/National Cancer Institute (NCI)] against ovarian cancer stem-like cells (CSC) using a resazurin-based cell cytotoxicity assay. Identified sets of active compounds were projected onto self-organizing maps to identify their putative cellular response groups. Results: From 793 screening compounds with evaluable data, 158 were found to have significant inhibitory effects on ovarian CSC. Computational analysis indicates that the majority of these compounds are associated with mitotic cellular responses. Conclusions: Our HTS has uncovered a number of candidate compounds that may, after further testing, prove effective in targeting both ovarian CSC and their more differentiated progeny. Keywords: High-throughput screening, Ovarian cancer, Cancer stem cells Background alternative strategies. One approach has been to evaluate Ovarian cancer is the most lethal of gynecological can- molecules known to be inhibitory against pathways cers [1] despite its typically high initial response rate to believed to be deregulated in CSC (e.g., the Hedgehog, chemotherapy [2]. -

Prevalence and Safety of Off-Label Use of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Older Patients with Breast Cancer: Estimates from SEER-Medicare Data

Supplemental online content for: Prevalence and Safety of Off-Label Use of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Older Patients With Breast Cancer: Estimates From SEER-Medicare Data Anne A. Eaton, MS; Camelia S. Sima, MD, MS; and Katherine S. Panageas, DrPH J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016;14(1):57–65 • eAppendix 1: J-Codes Representing Intravenous Chemotherapy • eAppendix 2: Established Sequential Adjuvant Chemotherapy Regimens for Breast Cancer • eTable 1: Patient Characteristics © JNCCN—Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network | Volume 14 Number 1 | January 2016 Eaton et al - 1 eAppendix 1: J-Codes Representing Intravenous Chemotherapy J-Code Agent J-Code Agent J9000 Injection, doxorubicin HCl, 10 mg J9165 Injection, diethylstilbestrol diphosphate, 250 J9001 Injection, doxorubicin HCl, all lipid mg formulations, 10 mg J9170 Injection, docetaxel, 20 mg J9010 Injection, alemtuzumab, 10 mg J9171 Injection, docetaxel, 1 mg J9015 Injection, aldesleukin, per single use vial J9175 Injection, Elliotts’ B solution, 1 ml J9017 Injection, arsenic trioxide, 1 mg J9178 Injection, epirubicin HCl, 2 mg J9020 Injection, asparaginase, 10,000 units J9179 Injection, eribulin mesylate, 0.1 mg J9025 Injection, azacitidine, 1 mg J9180 Epirubicin HCl, 50 mg J9027 Injection, clofarabine, 1 mg J9181 Injection, etoposide, 10 mg J9031 BCG (intravesical) per instillation J9182 Etoposide, 100 mg J9033 Injection, bendamustine HCl, 1 mg J9185 Injection, fludarabine phosphate, 50 mg J9035 Injection, bevacizumab, 10 mg J9190 Injection, fluorouracil, 500 mg J9040 Injection,