The Day the Bottle Did'nt Break

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trailer Boat Storage and Slipway Nauticalia Ferry

Trailer Boat Storage and Slipway Nauticalia Ferry Storage and Slipway Shepperton – Weybridge Prices are for payment in advance and include The Nauticalia Ferry continues a service that has operated FREE unlimited use of slipway during office hours, from this point for around 500 years, and enables people 7 days a week. walking or cycling the Thames Path to continue their Serving Thames Boats at Shepperton Lock Length of Boat Storage Per Qtr. Per Year journey past Shepperton Lock without being diverted by & Trailer Per Week the Wey Navigation. The ferry runs every 15 minutes and Up to 6 metres £100 £270 £1,037 you should ring the bell on the quarter hour if coming from 6-8 metres £150 £300 £1,152 the south (Weybridge) side to ensure the ferryman knows you are waiting. The bell on the Weybridge side is located Slipway Only at the bottom of the quayside steps. Self-service Slipway (Min 4 metre charge) Price per Metre SUMMER WINTER 7 Days a week during office hours £2.50 each way April - September October - March Car and Trailer Parking Monday to Friday Monday to Friday From 08:00 to 18:00 From 08:30 to 5:30 Parking Per Day SERVICES & PRICE LIST Saturday Saturday Free parking at weekends and bank holidays. £20 From 09:00 to 18:00 From 09:00 to 17:00 Spring 2018 Daily parking charge for cars plus trailer applies at all other times. Sunday Sunday From 10:00 to 18:00 From 10:00 to 17:00 FERRY RUNS EVERY 15 MINUTES IF REQUESTED BY RINGING THE BELL LOUD AND CLEARLY ON THE QUARTER HOURS Nauticalia Ferry Price List Adult Child Single £2.50 £1.25 -

Crown Copyright Catalogue Reference

(c) crown copyright Catalogue Reference:cab/66/9/30 Image Reference:0001 THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT SECRET. Copy,No. 26 W.P. (40) 250 (Also Paper No. C.O.S. (40) 534) July 5, 1940 TO BE KEPT UNDER LOCK It is requested that special care mai be ta&en to ensure the secrecy of this document T" o, 44) of the from 12 noon June 27th to 12 noon July 4th, [Circulated with the approval of the Chiefs of Staff.] Cabinet War Room. NAYAL SITUATION. General Review. THE outstanding event in the Naval Situation during the past week has been the action taken to prevent the French Fleet falling into enemy hands. At least 4 Italian submarines and one destroyer have been sunk in the Mediterranean. There has been a considerable reduction in the number of German U-boats on patrol. French Fleet. 2. The French failure to comply with their undertaking to prevent their fleet falling into the hands of our enemies as a result of the armistice necessitated action by us to that end on the 3rd July, on which, date the disposition of the principal French naval forces was as shown in Appendix IV. All vessels in British ports were seized. At Plymouth the seizure was effected without incident except for the submarine Surcouf, where 2 British officers were seriously wounded and 1 rating killed and 1 wounded. One French officer was also killed and 1 wounded. At Portsmouth a leaflet raid was carried out on the French ships for the crews' information and the ships successfully seized. -

In Pursuit of Accuracy: Innovati Ve Technology Outside the Comfort Zone: for Effi Cient Pile Installati on Upgrading the DCV BALDER

Dredging | Mining | Off shore Spring 2016 | E 8 MAIN FEATURES Making gains in mining Behind the scenes thanks to a new merger of a ship’s launch Customised soluti ons Partners for local development: for moti on compensati on our work with TNPA to improve South Africa’s dredging industry A fresh approach to jack-up design In pursuit of accuracy: innovati ve technology Outside the comfort zone: for effi cient pile installati on upgrading the DCV BALDER A SHIP’S LAUNCH What actually happens ABOUT ROYAL IHC behind the scenes? Royal IHC: providing sustainable services. From our head offi ce in Innovati ve soluti ons for mariti me service providers The Netherlands and with 3,000 employees working from sites and offi ces on a global basis, we are able MOTION COMPENSATION In an ever-changing politi cal and economic landscape, to ensure a local presence and support on every Royal IHC enables its customers to execute complex conti nent. Customised soluti ons projects from sea level to ocean fl oor in the most challenging of mariti me environments. We are a Dredging operators, oil and gas corporati ons, to miti gate risks reliable supplier of innovati ve and effi cient equipment, off shore contractors, mining houses and government Royal IHC vessels and services for the off shore, dredging and wet authoriti es all over the world benefi t from IHC’s high- mining markets. quality soluti ons and services. With our commitment In pursuit of P.O. Box 1 to technological innovati on, in which sustainability JACK-UP DESIGN With a history steeped in Dutch shipbuilding since and safety are key, we strive to conti nuously meet the 2960 AA Kinderdijk the mid-17th Century, we have in-depth knowledge specifi c needs of each customer in a rapidly evolving The Netherlands An integrated approach for and experti se of engineering and manufacturing high- world. -

Ship Launching in Small Shipyards

Ship Launching in Small Shipyards Edwin Salas Master Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the double degree: “Advanced Master in Naval Architecture” conferred by University of Liege "Master of Sciences in Applied Mechanics, specialization in Hydrodynamics, Energetics and Propulsion” conferred by Ecole Centrale de Nantes developed at West Pomeranian University of Technology, Szczecin in the framework of the “EMSHIP” Erasmus Mundus Master Course in “Integrated Advanced Ship Design” Ref. 159652-1-2009-1-BE-ERA MUNDUS-EMMC Supervisor: Prof. Tadeusz Graczyk, West Pomeranian University of Technology, Szczecin Reviewers: Prof. R. Bronsart,University of Rostock Prof. A. Hage, University of Liège Szczecin, February 2017 2 “EMSHIP” Erasmus Mundus Master Course, period of study September 2015 – February 2017 Declaration of Authorship I declare that this thesis and the work presented in it are my own and has been generated by me as the result of my own original research. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. Where the thesis is based on work done by myself jointly with others, I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. This thesis contains no material that has been submitted previously, in whole or in part, for the award of any other academic degree or diploma. I cede copyright of the thesis in favour of the University of West Pomeranian University of Technology, Szczecin Date: Signature 3 Edwin Salas CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... -

TAHITI NUI Tu-Nui-Ae-I-Te-Atua

TAHITI NUI Tu-nui-ae-i-te-atua. Pomare I (1802). ii TAHITI NUI Change and Survival in French Polynesia 1767–1945 COLIN NEWBURY THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF HAWAII HONOLULU Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880323 (PDF) 9780824880330 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. Copyright © 1980 by The University Press of Hawaii All rights reserved. For Father Patrick O’Reilly, Bibliographer of the Pacific CONTENTS Dedication vi Illustrations ix Tables x Preface xi Chapter 1 THE MARKET AT MATAVAI BAY 1 The Terms of Trade 3 Territorial Politics 14 Chapter 2 THE EVANGELICAL IMPACT 31 Revelation and Revolution 33 New Institutions 44 Churches and Chiefs 56 Chapter 3 THE MARKET EXPANDED 68 The Middlemen 72 The Catholic Challenge 87 Chapter 4 OCCUPATION AND RESISTANCE 94 Governor Bruat’s War 105 Governor Lavaud’s -

Maritime and Naval Buildings Listing Selection Guide Summary

Maritime and Naval Buildings Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https:// www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of-selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. England has the longest coastline in relation to its land mass in Europe: nowhere is very far from the sea. -

Port-Adelaide-Embracing-The-History-Booklet.Pdf

Port Adelaide Renewal Project www.ourport.com.au The full Cultural Mapping reports are available at: www.ourport.com.au/renewalintentions/resourcedocuments.aspx This document was published in August 2013 by Renewal SA. Embracing the History Port Adelaide Inner Harbour A snapshot of the Cultural Mapping and Survey Project Recording the history of Port Adelaide’s Inner Harbour A rich history of maritime stories and structures This left these hives of working life vacant; often surround the Port of Adelaide. In recognition of South with remnant industrial buildings and the effect of Australia’s oldest working port, the State Government environmental practices not acceptable today. initiated a comprehensive cultural mapping survey of But these remnants shine light on the fabric of lives lived the Inner Harbour in 2007. The result is a celebration in these places, the nature of work done, and activities of Port Adelaide’s social, economic and built heritage. and trades carried out; the labour, often back-breaking; The project features both a survey of the structures of the dangers; the families who lived and laboured there; the old working port and a broader cultural mapping and the people who risked their all in business and trade. program, to further investigate some of these places and working practices of the former Port Adelaide The experiences of other former industrial ports around waterfront. the world has shown how these sites can be seen as opportunities for renewal. The industrial waterfronts of places such as Port Adelaide were areas of intense and hard-working activity This booklet is a snapshot of the Cultural Mapping and until only a few decades ago. -

Shipbuilding Queen Mary 40 Luxury Liner Row in the 1950S 46 1946–1961 22

Number 315 • fall 2020 PowerT HE M AGAZINE OF E NGINE -P OWERED V ESSELS FRO M T ShipsHE S T EA M SHI P H IS T ORICAL S OCIE T Y OF A M ERICA ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Greek Conversions: Daphne & Danae 10 When Ellerman Ships flew the maple leaf 14 Ingalls The Cunard Story exhibit aboard Shipbuilding Queen Mary 40 luxury liner row in the 1950s 46 1946–1961 22 PLUS! SSHSa arriveS iN Home porT! 6 EXPERIenCE THE ACTIon of WORLD WAR II AFLoat! Aboard the Liberty Ship JOH N W. BROW N The SS JO HN W. B the great fleet of over 2,700ROW war-built Liberty Ships and the last operational N is one of the last operating survivors from troopship of World War II. The ship is a maritime museum and a memorial to the shipyard workers who built, merchant mariners who sailed, and the U.S. Navy Watch Our Website Armed Guard who defended the Liberty ships during World War II. The Joh for Our 2021 Cruise W. Bro wn is fully restored and maintained as close as possible to her World Schedule War II configuration. Visitors must be able to walk up steps to board the ship. N H H H H H H H H H H H H These exciting 6 hour day cruises Donate Online period entertainment and flybys (conditions permitting) of wartime aircraft. Tour to Support the on-board museums, crew quarters, bridge and much include more. lunch, See the music magnificent of the 40’s, John Brown 140-ton triple-expansion steam engine as it powers the ship through the water. -

WORKHORSE of the FLEET a History of the Liberty Ships OUR MISSION

WORKHORSE OF THE FLEET A History of the Liberty Ships OUR MISSION The mission of ABS is to serve the public interest as well as the needs of our members and clients by promoting the security of life and property and preserving the natural environment. HEALTH, SAFETY, QUALITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY We will respond to the needs of our members, clients and the public by delivering quality products and services in support of our Mission that provides for the safety of life and property and the protection of the natural environment. With the input and the participation of our workers, we are committed to continually improving the effectiveness of our HSQE performance and management system by identifying risks and opportunities that help to eliminate hazards and reduce risks and by providing safe and healthy working conditions for the prevention of work-related injury, ill health and pollution. We will comply with all applicable legal requirements as well as any additional requirements ABS subscribes to which relate to ABS and our HSQE aspects, objectives and targets. Workhorse of the Fleet by Gus Bourneuf Jr. A history of the design and experiences of the Liberty Ships built by American Shipbuilders during WWII. Workhorse of the Fleet Published by: American Bureau of Shipping 1701 City Plaza Drive Spring, TX 77389 USA Produced by: ABS External Affairs Copyright © 1990, 2008 by ABS. Printed and bound in the United States of America First Revised Edition All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review or for personal use. -

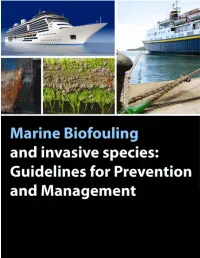

Marine Biofouling and Invasive Species: Guidelines for Prevention and Management

MARINE BIOFOULING AND INVASIVE SPECIES: GUIDELINES FOR PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1 Invasive species in the marine environment An invasive alien species is one which has been introduced by human activity to a new geographic area or ecosystem outside of its natural distribution range, and which has then established and spread threatening ecosystems, habitats and/or other species, and potentially causing economic and/or environmental damage, or harm to human health. It is important to note, however, that native species may also become invasive, usually under altered environmental conditions. Invasive Alien Species in the marine environment are called by a variety of names including Introduced Marine Pests (IMPs) (Australia and New Zealand), Aquatic Nuisance Species (ANS) (United States), and Harmful Aquatic Organisms (IMO Ballast Water Convention). For a number of marine species, the original, natural distribution has been blurred by centuries of transfers via sailing ships, canals, barges, aquaculture, etc., so that it is now difficult to tell whether they are alien or not. In fact, in some regions many historical introductions had been assumed to be part of the native marine community until recent studies raised questions. Examples include several common fouling organisms and wood- borers, such as the infamous bivalve ‘shipworm’ (Teredo navalis), the ship or striped barnacle (Balanus amphitrite), both blue (Mytilus) and brown (Perna) mussel complexes and some oyster species. These widespread and so-called ‘cosmopolitan’ marine species are known as cryptogenic species (Carlton, 1996a). Invasive alien species are now generally recognised as one of the greatest threats to biodiversity globally. In marine and coastal environments, invasive species have been identified as one of the four greatest threats to the world’s oceans along with: • land-based sources of marine pollution, • over-exploitation of living marine resources, and • physical alteration/destruction of marine habitats. -

UK Unique Slipway Location Codes

Unique Slipway July 2008 Location Codes RNLI Slipway abbreviations for creating Unique Slipway Location Codes (USLCs) BDN Broad Haven CHL Church Lane Pullover DSL Dores Loch Ness BDR Broadford Sutton-on-Sea DNO Dorlin (Private) Please use the suggested local authority abbreviations below to create your USLCs. If your area is missing BNQ Brockhampton Quay CHS Church Street DEO Dornie from the table please use the system outlined in the document The RNLI’s guide to slipway safety signs and Brockhampton Isleworth London symbols to create an abbreviation. Check that the abbreviation you create does not duplicate any of those DHO Dornoch CNM Clan Morrison Hotel Sunart listed below. BHU Brough Slip Thurso DTS Dovercourt Seafront Harwich CHR Claxheugh Rock BLQ Brunel Quay Neyland DYO Downderry Submit your USLCs to your Coastguard contact using the registration form on page 11 of this document. CNL Clevedon BSH Bucklers Hard DSM Drumaheglis Marina BLB Bull Bay Amlwch CYN Cley Next the Sea Ballymoney CSQ Cobbs Quay Marina Poole AEB Abercastle BAL Bala Lake BKS Black Swan Sailing Club BLN Bull Nose Blackpool DHU Dunbeath CEF Coble Landing Filey AYB Aberdovey BYB Balcary Bay Auchencairn Wokingham BEM Bure Marine Great Yarmouth DNM Duncan Mills Slip Balloch CRG Coldharbour Gosport AYE Abereiddy BYP Ballnacorthy Pier BSL Blackness BDD Burghead Harbour Ramp DMS Dundrum Slip Dundrum Burghead CHO Combwich AHB Abersoch Beach Maree Oranmore BRT Blacktar Haverfordwest DEH Dunure Harbour BMO Burnham Overy Staithe CNN Common Staithe Quay AHL Abersoch Land -

Interface Land, Chatham Supplementary Planning Document June 2018

1 Development Brief: Interface Land, Chatham Supplementary Planning Document June 2018 Development Brief v4 - June 2018.indd 1 07/06/2018 17:13:00 2 Medway Council Gun Wharf Dock Road Chatham Kent ME4 4TR Development Brief v4 - June 2018.indd 2 07/06/2018 17:13:00 Medway Council – Chatham Interface Land Development Brief – Foreword 3 Foreword This document describes an exciting regeneration opportunity for two sites within the former royal dockyard at Chatham, an area of the highest historic importance for its role in our national story. The sites lie where the core of the successfully regenerated historic dockyard undertaken by Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust (CHDT), abuts the modern Dockside retail and leisure area, and beyond that the Pembroke University Campus. The river Medway lies west of the sites and directly adjoins one of these. The sites are well located for road, rail and public transport, footpaths, cycleways, and river access opportunities. These important and prominent locations have the potential to create a new benchmark for future place-making and residential led mixed use development, providing a key part in the success of Medway as a Smart and Sustainable University Waterfront City for the 21st Century. Imagery ©2017 Google Maps / Google Earth Development Brief v4 - June 2018.indd 3 07/06/2018 17:13:01 Medway Council – Chatham Interface Land Development Brief – Foreword 4 Both sites benefit from the outstanding There is a need for contextual solutions that For centuries the Navy enjoyed quality of their history and the heritage fit with the outstanding heritage of the setting provided by the dockyard and river.