“Kid-Focused, Coach-Driven: What Training Is Needed?” Roundtable Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Job Description: Coach Mentor (Multi-Sports) (Basketball / Athletics / NFL / Handball / Fitness / Play Leaders) Key Responsibil

Job Description: Coach Mentor (Multi-sports) (Basketball / Athletics / NFL / Handball / Fitness / Play Leaders) RSports is a dynamic forward-thinking company with key strategic relationships, and is rapidly becoming a leading force in sports education in the People’s Republic of China. Working from our head office in Beijing the coach mentor will contribute to a variety of national, regional, and local projects linked to the further development of PE and mass participation sports. This is an outstanding opportunity to help shape the future of sports education in China. Key responsibilities Deliver coach education / training programme to PE teachers, student teachers, and sport specific coaches in line with the RS development principles Deliver demonstration PE classes to a variety of audiences Deliver internal training programme to RS coaches in relevant sport Ongoing mentoring and evaluation of RS coaching team Contribute to the development of sports specific PE Curricula in relevant sport Contribute to the continuing development of internal and external coach education programmes in relevant sport Contribute to the development and management of festivals, carnivals, and special events in relevant sport Contribute to the compilation and development of a comprehensive advanced development curriculum in relevant sport Contribute to the development of RS vision for the future of Chinese sports education Assist in the recruitment of delivery staff for ongoing projects (both Foreign and Local Staff) Salary: Negotiable (dependent on experience) Person Spec: Experienced coach / PE teacher with a passion for developing grassroots sports, and a creative, adaptable personality. Previous experience of leading PE classes in schools is essential. Previous experience working for a professional sports club or affiliated development scheme will be preferred. -

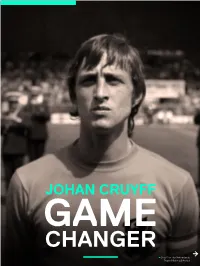

Johan Cruyff Game Changer

JOHAN CRUYFF GAME CHANGER Cruyff for the Netherlands. Photo: Nationaal Archief Cruyff for Ajax (right) against Feyenoord, September 1967. Photo: Nationaal Archief Jon Hoggard Winner of the Ballon d’Or an incredible three times, Cruyff started his footballing career at Ajax, where he led the Dutch giants to 23 eight league titles and three consecutive It is difcult to overstate just European Cups in 1971, 1972 and 1973. how much of an infuence Dutch football legend Johan Cruyf has had on the sport. Winner of the Ballon d’Or an incredible In the early 1970s came the incredible three times, Cruyf started his run of three consecutive European From his time on the pitch, footballing career at Ajax, where he Cup wins between 1971 and 1973, starring for Ajax, Barcelona led the Dutch giants to eight league with Cruyf scoring twice in the fnal and the Dutch national side, titles and three consecutive European of the 1972 competition against to his time in management Cups. He joined the club aged 10, Internazionale. In 1971 Johan had been and was a talented baseball player named as European Footballer of the at the same institutions, alongside his football development Year. Cruyf has always been at until he decided to concentrate on Following the 1973 European Cup the cutting edge of football football at age 15. He frst established win, Johan moved to Barcelona in a development. himself in the Ajax frst team aged 18 in world record-breaking transfer. He 1965–66, a season in which he scored immediately made an impact and 25 goals in 23 games as Ajax won the helped the Catalans to their frst league championship. -

100 Coaches to Remember Final

NORTH CAROLINA HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION 100 TO REMEMBER – COACHES Gerald Allen Shelby Enjoyed a 38-year stint at Shelby, including 21 years as head football coach and 26 seasons leading the track program…his football teams won 11 conference championships and five Western North Carolina High School Activities Association titles…overall football record stands at 175-49-14…honored by coaching the North Carolina Shrine Bowl team in 1973 and coached at the East-West all-star game in 1970…member of the Cleveland County and NCHSAA Halls of Fame. Stuart Allen Myers Park Compiled an impressive 11 NCHSAA state track championships from 1956 to ’71 at Myers Park…additionally guided four Myers Park teams to cross country state crowns…also served as a head wrestling coach and football assistant during the same stint at Myers Park…coached several more years at John Handley High in Winchester, Virginia after leaving the Charlotte school…2008 inductee into the NCHSAA Hall of Fame. Rosalie Bardin Southern Nash Significant contributions to high school athletics as both a coach and administrator…majority of career spent with Southern Nash where she coached women’s basketball (12 years), volleyball (18 years), track and field (7 years) and softball (24 years)…also served as cheerleading coach and athletic trainer during lengthy stint at Southern Nash…shifted to administration in 1998, serving as principal at Southern Nash…two-time Nash-Rocky Mount Principal of the Year and an inductee into the NCHSAA Hall of Fame. Frank Barger Hickory Achieved an outstanding record during 32 years as the head football coach at Hickory High…also amassed numerous conference crowns with career coaching mark of 273- 120-5 in fotoball…compiled over 625 victories and 29 conference titles coaching four additional sports to football…retired in 1984 and is a member of the Catawba County Sports Hall of Fame…joined NCHSAA Hall of Fame in class of 1993. -

Head Coaches Responsibilities ➢ Set up Outline for Daily Practices

Table of Contents Letter to Coaches and Parents 3 1.00 Purpose 4 2.00 League Management 4 3.00 Communication 4 4.00 Weather Policy 5 5.00 Coaches & Assistants 5 6.00 Uniforms and Equipment 6 8.00 Code of Conduct & Penalties 6 9.00 Miscellaneous Recap 7 10.00 Lightning Policy 7 11.00 Tornado Policy 8 Heat-Related Illness Info 10 Concussion Info 11 Coach / Parent / Player responsibilities 12 Practices/Games Info 13 Important Phone Numbers WE Hunt Recreation Center ................................................... 557-9600 Weather Hotline ...................................................................... 557-2939 Chris Champion-Recreation Programs Manager...……………567-4031 Steve Johnson-Recreation Programs Specialist……………...557-9601 Austin Ohms-Recreation Programs Specialist ........................ 577-3124 Kristen Denton-Hunt Community Center Manager……………557-6293 Adam Huffman-Parks and Recreaion Assistant Director…….557-2925 LeeAnn Plumer-Parks and Recreation Director ...................... 577-3127 A Letter from Holly Springs Parks and Recreation Athletic Department Dear Coaches and Parents, We would like to take this opportunity to thank all the parents and coaches involved with our Intro to Football program. Everyone is working hard to make this season fun and successful. The goal of the Parks and Recreation Intro to Football program is to provide quality instruction which promotes sportsmanship, teamwork, development, participation and fun; individually, to develop technical skills which will enhance the ability, desire and confidence of each player. It is the coach’s responsibility to instill this concept into all participants and their parents. If anyone associated with your team loses sight of these objectives, please remind them that this is about children playing a game. -

I Am a New Baseball Coach at My School…..”What Can I Do”?

I Am a New Baseball Coach at my School…..”What Can I Do”? Ok, you’re a school baseball coach. You coached at a different school last year or maybe did not coach at all last year and you have been hired at a ‘new’ school taking over the baseball program. You want to do everything possible to establish your program and improve your chances to compete – ESPECIALLY since you are new. You want to follow the rules but you just need to know what those rules are…so what is it you CAN do between now and next season? Everything you WANTED to know and probably some you DIDN’T want to know is explained below. Comments First, understand that OHSAA regulations are created and approved each year by the schools – the very schools where you and other coaches are employed. And, they are by design. Kids need a break – COACHES need a break. IF you are concerned about ‘getting them college scholarships’, stop and realize that all statistics point to the success at the ‘next level’ correlates to athletes that play multiple sports. And, nearly every sports psychologist agrees it is nearly impossible to maintain a ‘hungry’ student-athlete when they are asked to be under the gun for 12 months a year. Just the Facts - All Coaches, whether are PAID or VOLUNTEER are under the same regulations. There is no distinction between a paid coach or a volunteer coach with one exception – the volunteer coach receives no financial compensation. - Out of Season Regulations are in place for Junior High/Middle School as well as High School teams - All references to a coach or player are where that coach or player coached or played the previous season. -

Job Description National Head Coach Profile JOB SUMMARY

Job Description National Head Coach Profile The Afghanistan Cricket Board was established in 2001. It is an independent and specialized organization in the field of Cricket. It works for the development of cricket, and players in the country, and organizes different formats of opportunities aiming to improve cricket and support players. ACB is an Equal Opportunity Employer. Therefore, applicants are considered for employment based on their skills, abilities, and experience. JOB SUMMARY The National Head Coach is competent and qualified cricket professional who is responsible to the Afghanistan Cricket Board for the delivery of high quality and international standard coaching with the aim of improving performance and results of the Afghanistan National Cricket Team with an over‐riding emphasis on quality at all levels. REPORTING The coach reports to the ACB Chief Executive Officer (CEO) through him to the ACB Chairman. He will maintain regular and open communication with them and will provide; Formal written monthly reports on activities, developments and important issues/problems. Formal written reports on player performance, fitness, and appraisals as required for the player’s contract. Formal written reports for major camps, matches, tournament and activities. COLLABORATION The National Head Coach will collaborate closely with; The board and its Chairman, the CEO, Cricket Operations and Selection Committee(s). The Coach of the National Cricket Academy Other Coaches in working to develop the skills of the national teams Senior Management in developing ACB proposals, work plans, and other master plans. SUPERVISING The National Head Coach supervises coaches, other training assistants, as well as having an advisory role in the planning of the development and training of domestic coaches. -

POSITION DESCRIPTION Job Title: Head Varsity Baseball Coach Reports To: Athletic & Activities Director Position Summary

POSITION DESCRIPTION Job Title: Head Varsity Baseball Coach Reports to: Athletic & Activities Director Position Summary: The Head Varsity Baseball Coach will have considerable knowledge of the sport, rules and coaching experience. The Coach will embrace the philosophy, faith-based beliefs and Code of Conduct for SMCS Athletics as established by the SMCS Board of Trustees and the Green Bay Diocese, exemplifying the highest standards of sportsmanship, our Catholic faith and conduct. Job Duties: Provide overall leadership for the SMCS Baseball program and perform all services thereof as scheduled and/or directed by the SMCS Athletic & Activities Director. Present for approval to the SMCS Athletic & Activities Director a schedule for practices, scrimmages, training sessions and any other activities necessary to field a competitive team for the SMCS Sport program. Responsible for the use, care, storage and inventory of all SMCS athletic equipment issued for use by the Sport program including, but not limited to uniforms, warm-up apparel, balls and all other equipment necessary for practice and games/matches conducted by the Sport program. Proactively ensure the proper use, care, cleaning and maintenance of all SMCS facilities utilized by the Sport program for practices and games/matches. Adhere to all rules, regulations and policies as mandated by the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association (WIAA). Promote the sport with students, alumni, and members of the community. Provide oversight of all hiring and supervision of JV Head Coach and assistant coaches with SMCS Athletic and Activities Director’s approval. Adhere to the policies, regulations and directives of SMCS Athletics as defined by the SMCS Athletic and Activities Director and/or the SMCS Athletic Committee. -

Coaching MASTER in JOHAN CRUYFF INSTITUTE English Edition Amsterdam

Educating the next generation of Leaders in Sport Management MASTER IN Coaching English edition JOHAN CRUYFF INSTITUTE Amsterdam 05 WELCOME 06 COACHING ACCORDING TO THE VISION OF JOHAN CRUYFF 08 PROFESSORS 08 PERSONAL COACHING 09 STUDENTS 10 TEACHING METHOD 11 LEARNING OUTCOMES 12 CLASSES 13 NETWORK AND SERVICES 15 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 15 DIPLOMA 15 ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS AND ENROLLMENT The most important aspect of coaching is what you see in a person. You need to get to know their habits and character. What background do they have? As a coach you have the responsibility to educate players the right way. Johan Cruyff Founder, Johan Cruyff Institute Welcome to the Master in Coaching at the Johan Cruyff Institute in Amsterdam. The Master in Coaching aims to foster students’ self-knowledge and self-development with the aim to improve their abilities as a (sports) coach or manager. Throughout the academic year, we motivate and support students in every way we can, to facilitate their personal development. Professors and staff ensure all students, each with a different background and experiences, will be challenged in their learning. It will be a new step in students’ personal development towards improving their individual and team performance. On completion of the program, students will have developed their personal coaching style and they will be able to put this style into practice. They will know what is needed for individual and team success and how to manage this success. This brochure will give you detailed information about the Master in Coaching program. For further information, or to request a personal meeting, please contact my colleagues at the Johan Cruyff Institute who will be delighted to help you. -

USA Floorball Board Meeting February 17, 2019 1

USA Floorball Board Meeting USA Floorball Board Meeting Minutes February 17, 2019, 9.00 AM PST Participants; David Nilsson, Calle Karlsson, Adam Troy, Anders Buvarp, Kim Aaltonen. Approve meeting agenda and select note taker. Agenda approved and David Nilsson selected to lead the meeting and take notes. Quorum requirements were met. U19 Women’s National Team (Anders Buvarp) Report from Anders Buvarp: Brian Radichel has invited a Women's team for Texas Open in three weeks. Since we are short of women being able to participate, I've invited the U19 girls to join. We have a girl coming from Orlando Vikings Floorball* Need players born 1/1/2001 to 5/5/2005 for 2020 WFC. We intend to participate in the SGA in August. Looking at hostels for 2020 WFC; Svartbäckens vandrarhem and Uppsala Vandrarhem. Camp will be at "Mallboden Hostel" in Motala, Sweden starting 5/2/2020 and ending 5/5/2020. WFC is 5/6/2020 to 5/10/2020. No news from IFF regarding the 2020 WFC qualifications. No news from IFF on the 2020 WFC roster/staff size. U19 Men’s National Team (Anders Buvarp) Report from Kenton Walker: 6 players at Detroit camp 15 field players committed for Halifax 1 new field player to be added from Detroit 1 goalie from Sweden who said this week that his passport will be issued this month (fingers crossed!) Focus on fundraising and Halifax logistics now Planning 100 stick sponsorship from Accufli and turning into $$ through selling raffle tickets 6 Halifax roster players and other developmental players will play in Texas Open Women’s National Team (Alyssa Zinsser Hall) Calle Karlsson said he had discussions with John Liljelund of the IFF about the fact that the WFCQ only qualifies the USA or Canada. -

Questions and Answers (Q&A)

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS (Q&A) 17.1.0 SCHOOL YEAR Q&A: When do the WIAA rules take effect? The school year begins on August 1 and ends the first day following the spring sports tournaments. 17.2.2 IN-SEASON Q&A-1: My team did not qualify for postseason playoffs. How long can we continue to practice as a team with our coach? The season concludes with the final day of the state event in for that sport. Even though the team did not qualify, your coach could continue to coach your team until the conclusion of the state tournament for that sport. Q&A-2: Our basketball team is planning to play in a summer basketball tournament on the Sunday after the spring tournaments. With the impending weather reports, the state softball tournament may be postponed until after that date. Will our coach violate the out-of-season rule if she coaches us on Sunday, even though the softball tournament may not be completed? NO. Coaches cannot be responsible for the spring tournament being postponed due to inclement weather. 17.3.4 ALTERNATE SEASON CONTESTS Q&A: Our league plays girls tennis in the fall, but we would like to hold the final district qualifying event one week prior to the state tournament. Is it ok for our team to begin practice 20 school days prior to the district qualifying tournament? NO. Your team may begin practice twenty (20) days prior to the first day of the state tournament, with any contests held only after ten (10) practices have been completed. -

Coaches' Association

COACHES’ ASSOCIATION BRUCE G. WOOD LIFE MEMBER 16 May 2017 One of the highlights of the Coaches’ Association’s 8th Annual General Meeting on 16-May-17 was the induction of Bruce Wood as our third Life Member, following Tom Richmond OAM (2014) and Rod Hokin (2015). Criteria Life Membership is the most significant award that can be bestowed by our association. In accordance with the HKHDCCA Constitution (2b), the following criteria must be met: The members of the association may approve, in exceptional circumstances, that an individual be admitted for Life Membership, subject to meeting at least two of the following criteria: • Performed creditably as an active cricket coach for HKHDCCA (Coaches’ Association) and/or in HK&HDCA club or representative competitions for a period of at least 10 years; • Served with distinction as an office bearer on the HKHDCCA Executive Committee for at least 5 years; and • Made an outstanding, long-term contribution to cricket coaching within the Association and/or the local cricket community. Nomination Rod Hokin, Head Coach (& Life Member) of the Coaches’ Association, was the nominator for this award and made the following observations regarding Bruce Wood’s suitability for Life Membership: Bruce has been coaching cricket in this district for two decades, having coached 25 club, representative, touring or school teams since 1997. He established and became the inaugural President of the Coaches’ Association (HKHDCCA) in 2010 and has been the driving force behind our growth and success over the past 7 years. He has displayed amazing vision, innovation, determination and marketing skills to continually expand our coaching programs and to ensure that each one is enjoyable and beneficial for the participants. -

Floorball Rules

RCSSC FLOORBALL RULEBOOK These rules were last updated on December 1, 2018. RULE 1: TEAMS AND PLAYERS Section 1. Team Formation 1. Leagues Offered: The RCSSC offers two floorball leagues: SUPER SOCIAL and EXTREME SOCIAL. • SUPER SOCIAL is designed for teams and individuals who love to socialize and have GOOD athletic skills. • EXTREME SOCIAL is designed for teams and individuals who love to socialize and have LIMITED athletic skills. 2. Season. Floorball is offered on Tuesdays in the starting at 6:30 PM or later. All games will be played at the RCSSC Annex, 7505 Ranco Rd., Henrico, VA 23228. 3. Number of Players. All teams must have at least 12 players, but there is no maximum. All players must be listed on the roster and sign the RCSSC waiver to participate. 4. Adding Players. Players may be added at any time until the final tee shirt order date. After that time, until the third week of play, a team must drop a player before it may add a player. The dropped player must provide his or her tee shirt to the added player. After the third week of play, team rosters are frozen. Teams must provide an updated roster to the Commissioner at the end of the third week. See the Commissioner for additional roster forms. 5. Players on the Field. A team can field no more than six players at a time. At least two of the players on the field must be women. A team must have at least five players, and at least two women, present at game time to avoid a forfeit.