Exploitation of a Seasonal Resource by Nonbreeding Plain and White-Crowned Pigeons: Implications for Conservation of Tropical Dry Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nest Density and Success of Columbids in Puerto Rico ’

The Condor98:1OC-113 0 The CooperOrnithological Society 1996 NEST DENSITY AND SUCCESS OF COLUMBIDS IN PUERTO RICO ’ FRANK F. RIVERA-MILAN~ Department ofNatural Resources,Scientific Research Area, TerrestrialEcology Section, Stop 3 Puerta. de Tierra, 00906, Puerto Rico Abstract. A total of 868 active nests of eight speciesof pigeonsand doves (columbids) were found in 210 0.1 ha strip-transectssampled in the three major life zones of Puerto Rico from February 1987 to June 1992. The columbids had a peak in nest density in May and June, with a decline during the July to October flocking period, and an increasefrom November to April. Predation accountedfor 8 1% of the nest lossesobserved from 1989 to 1992. Nest cover was the most important microhabitat variable accountingfor nest failure or successaccording to univariate and multivariate comparisons. The daily survival rate estimates of nests constructed on epiphytes were significantly higher than those of nests constructedon the bare branchesof trees. Rainfall of the first six months of the year during the study accounted for 67% and 71% of the variability associatedwith the nest density estimatesof the columbids during the reproductivepeak in the xerophytic forest of Gulnica and dry coastal forest of Cabo Rojo, but only 9% of the variability of the nest density estimatesof the columbids in the moist montane second-growthforest patchesof Cidra. In 1988, the abundance of fruits of key tree species(nine speciescombined) was positively correlatedwith the seasonalchanges in nest density of the columbids in the strip-transects of Cayey and Cidra. Pairwise density correlationsamong the columbids suggestedparallel responsesof nestingpopulations to similar or covarying resourcesin the life zones of Puerto Rico. -

Plant Section Introduction

Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 RE-INTRODUCTION PRACTITIONERS DIRECTORY 1998 Compiled and Edited by Pritpal S. Soorae and Philip J. Seddon Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 © National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development, 1998 Printing and Publication details Legal Deposit no. 2218/9 ISBN: 9960-614-08-5 Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 Copies of this directory are available from: The Secretary General National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development Post Box 61681, Riyadh 11575 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Phone: +966-1-441-8700 Fax: +966-1-441-0797 Bibliographic Citation: Soorae, P. S. and Seddon, P. J. (Eds). 1998. Re-introduction Practitioners Directory. Published jointly by the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Re-introduction Specialist Group, Nairobi, Kenya, and the National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 97pp. Cover Photo: Arabian Oryx Oryx leucoryx (NWRC Photo Library) Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 CONTENTS FOREWORD Professor Abdulaziz Abuzinadai PREFACE INTRODUCTION Dr Mark Stanley Price USING THE DIRECTORY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PART A. ANIMALS I MOLLUSCS 1. GASTROPODS 1.1 Cittarium pica Top Shell 1.2 Placostylus ambagiosus Flax Snail 1.3 Placostylus ambagiosus Land Snail 1.4 Partula suturalis 1.5 Partula taeniata 1.6 Partula tahieana 1.7 Partula tohiveana 2. BIVALVES 2.1 Freshwater Mussels 2.2 Tridacna gigas Giant Clam II ARTHROPODS 3. ORTHOPTERA 3.1 Deinacrida sp. Weta 3.2 Deinacrida rugosa/parva Cook’s Strait Giant Weta Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 3.3 Gryllus campestris Field Cricket 4. LEPIDOPTERA 4.1 Carterocephalus palaemon Chequered Skipper 4.2 Lycaena dispar batavus Large Copper 4.3 Lycaena helle 4.4 Lycaeides melissa 4.5 Papilio aristodemus ponoceanus Schaus Swallowtail 5. -

AOU Checklist of North and Middle American Birds

12/17/2014 AOU Checklist of North and Middle American Birds Home Checklists Publica tioSneasrch Meetings Membership Awards Students Resources About Contact AOU Checklist of North and Middle American Birds Browse the checklist below, or Search Legend to symbols: A accidental/casual in AOU area H recorded in AOU area only from Hawaii I introduced into AOU area N has not bred in AOU area, but occurs regularly as nonbreeding visitor † extinct * probably misplaced in the current phylogenetic listing, but data indicating proper placement are not yet available Download a complete list of all bird species in the North and Middle America Checklist, without subspecies (CSV, Excel). Please be patient as these are large! This checklist incorporates changes through the 54th supplement. View invalidated taxa class: Aves order: Tinamiformes family: Tinamidae genus: Nothocercus species: Nothocercus bonapartei (Highland Tinamou, Tinamou de Bonaparte) genus: Tinamus species: Tinamus major (Great Tinamou, Grand Tinamou) genus: Crypturellus species: Crypturellus soui (Little Tinamou, Tinamou soui) species: Crypturellus cinnamomeus (Thicket Tinamou, Tinamou cannelle) species: Crypturellus boucardi (Slatybreasted Tinamou, Tinamou de Boucard) species: Crypturellus kerriae (Choco Tinamou, Tinamou de Kerr) order: Anseriformes family: Anatidae subfamily: Dendrocygninae genus: Dendrocygna species: Dendrocygna viduata (Whitefaced WhistlingDuck, Dendrocygne veuf) species: Dendrocygna autumnalis (Blackbellied WhistlingDuck, Dendrocygne à ventre noir) species: -

Neotropical News Neotropical News

COTINGA 1 Neotropical News Neotropical News Brazilian Merganser in Argentina: If the survey’s results reflect the true going, going … status of Mergus octosetaceus in Argentina then there is grave cause for concern — local An expedition (Pato Serrucho ’93) aimed extinction, as in neighbouring Paraguay, at discovering the current status of the seems inevitable. Brazilian Merganser Mergus octosetaceus in Misiones Province, northern Argentina, During the expedition a number of sub has just returned to the U.K. Mergus tropical forest sites were surveyed for birds octosetaceus is one of the world’s rarest — other threatened species recorded during species of wildfowl, with a population now this period included: Black-fronted Piping- estimated to be less than 250 individuals guan Pipile jacutinga, Vinaceous Amazon occurring in just three populations, one in Amazona vinacea, Helmeted Woodpecker northern Argentina, the other two in south- Dryocopus galeatus, White-bearded central Brazil. Antshrike Biata s nigropectus, and São Paulo Tyrannulet Phylloscartes paulistus. Three conservation biologists from the U.K. and three South American counter PHIL BENSTEAD parts surveyed c.450 km of white-water riv Beaver House, Norwich Road, Reepham, ers and streams using an inflatable boat. Norwich, NR10 4JN, U.K. Despite exhaustive searching only one bird was located in an area peripheral to the species’s historical stronghold. Former core Black-breasted Puffleg found: extant areas (and incidently those with the most but seriously threatened. protection) for this species appear to have been adversely affected by the the Urugua- The Black-breasted Puffleg Eriocnemis í dam, which in 1989 flooded c.80 km of the nigrivestis has been recorded from just two Río Urugua-í. -

Appendix S1. List of the 719 Bird Species Distributed Within Neotropical Seasonally Dry Forests (NSDF) Considered in This Study

Appendix S1. List of the 719 bird species distributed within Neotropical seasonally dry forests (NSDF) considered in this study. Information about the number of occurrences records and bioclimatic variables set used for model, as well as the values of ROC- Partial test and IUCN category are provide directly for each species in the table. bio 01 bio 02 bio 03 bio 04 bio 05 bio 06 bio 07 bio 08 bio 09 bio 10 bio 11 bio 12 bio 13 bio 14 bio 15 bio 16 bio 17 bio 18 bio 19 Order Family Genera Species name English nameEnglish records (5km) IUCN IUCN category Associated NDF to ROC-Partial values Number Number of presence ACCIPITRIFORMES ACCIPITRIDAE Accipiter (Vieillot, 1816) Accipiter bicolor (Vieillot, 1807) Bicolored Hawk LC 1778 1.40 + 0.02 Accipiter chionogaster (Kaup, 1852) White-breasted Hawk NoData 11 p * Accipiter cooperii (Bonaparte, 1828) Cooper's Hawk LC x 192 1.39 ± 0.06 Accipiter gundlachi Lawrence, 1860 Gundlach's Hawk EN 138 1.14 ± 0.13 Accipiter striatus Vieillot, 1807 Sharp-shinned Hawk LC 1588 1.85 ± 0.05 Accipiter ventralis Sclater, PL, 1866 Plain-breasted Hawk LC 23 1.69 ± 0.00 Busarellus (Lesson, 1843) Busarellus nigricollis (Latham, 1790) Black-collared Hawk LC 1822 1.51 ± 0.03 Buteo (Lacepede, 1799) Buteo brachyurus Vieillot, 1816 Short-tailed Hawk LC 4546 1.48 ± 0.01 Buteo jamaicensis (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Red-tailed Hawk LC 551 1.36 ± 0.05 Buteo nitidus (Latham, 1790) Grey-lined Hawk LC 1516 1.42 ± 0.03 Buteogallus (Lesson, 1830) Buteogallus anthracinus (Deppe, 1830) Common Black Hawk LC x 3224 1.52 ± 0.02 Buteogallus gundlachii (Cabanis, 1855) Cuban Black Hawk NT x 185 1.28 ± 0.10 Buteogallus meridionalis (Latham, 1790) Savanna Hawk LC x 2900 1.45 ± 0.02 Buteogallus urubitinga (Gmelin, 1788) Great Black Hawk LC 2927 1.38 ± 0.02 Chondrohierax (Lesson, 1843) Chondrohierax uncinatus (Temminck, 1822) Hook-billed Kite LC 1746 1.46 ± 0.03 Circus (Lacépède, 1799) Circus buffoni (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Long-winged Harrier LC 1270 1.61 ± 0.03 Elanus (Savigny, 1809) Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 29/09/2021. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

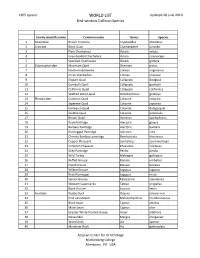

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Baseline Ecological Inventory for Three Bays National Park, Haiti OCTOBER 2016

Baseline Ecological Inventory for Three Bays National Park, Haiti OCTOBER 2016 Report for the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) 1 To cite this report: Kramer, P, M Atis, S Schill, SM Williams, E Freid, G Moore, JC Martinez-Sanchez, F Benjamin, LS Cyprien, JR Alexis, R Grizzle, K Ward, K Marks, D Grenda (2016) Baseline Ecological Inventory for Three Bays National Park, Haiti. The Nature Conservancy: Report to the Inter-American Development Bank. Pp.1-180 Editors: Rumya Sundaram and Stacey Williams Cooperating Partners: Campus Roi Henri Christophe de Limonade Contributing Authors: Philip Kramer – Senior Scientist (Maxene Atis, Steve Schill) The Nature Conservancy Stacey Williams – Marine Invertebrates and Fish Institute for Socio-Ecological Research, Inc. Ken Marks – Marine Fish Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment (AGRRA) Dave Grenda – Marine Fish Tampa Bay Aquarium Ethan Freid – Terrestrial Vegetation Leon Levy Native Plant Preserve-Bahamas National Trust Gregg Moore – Mangroves and Wetlands University of New Hampshire Raymond Grizzle – Freshwater Fish and Invertebrates (Krystin Ward) University of New Hampshire Juan Carlos Martinez-Sanchez – Terrestrial Mammals, Birds, Reptiles and Amphibians (Françoise Benjamin, Landy Sabrina Cyprien, Jean Roudy Alexis) Vermont Center for Ecostudies 2 Acknowledgements This project was conducted in northeast Haiti, at Three Bays National Park, specifically in the coastal zones of three communes, Fort Liberté, Caracol, and Limonade, including Lagon aux Boeufs. Some government departments, agencies, local organizations and communities, and individuals contributed to the project through financial, intellectual, and logistical support. On behalf of TNC, we would like to express our sincere thanks to all of them. First, we would like to extend our gratitude to the Government of Haiti through the National Protected Areas Agency (ANAP) of the Ministry of Environment, and particularly Minister Dominique Pierre, Ministre Dieuseul Simon Desras, Mr. -

SERDP Project ER18-1653

FINAL REPORT Approach for Assessing PFAS Risk to Threatened and Endangered Species SERDP Project ER18-1653 MARCH 2020 Craig Divine, Ph.D. Jean Zodrow, Ph.D. Meredith Frenchmeyer Katie Dally Erin Osborn, Ph.D. Paul Anderson, Ph.D. Arcadis US Inc. Distribution Statement A Page Intentionally Left Blank This report was prepared under contract to the Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP). The publication of this report does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official policy or position of the Department of Defense. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of Defense. Page Intentionally Left Blank Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. -

Endangered Species Act a Record of Success Table of Contents

AMERICAN BIRDS 2016 ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT A RECORD OF SUCCESS TABLE OF CONTENTS RECOVERY OF ESA-LISTED BIRDS .......................................................................................................................3 ESA Recovery Success Rate: Results ...........................................................................................................6 How Birds Benefit from ESA Listing ............................................................................................................7 History and Impact of the ESA .....................................................................................................................9 The ESA and Landowners ............................................................................................................................ 11 ABC’s ESA Actions .........................................................................................................................................12 SPECIES ACCOUNTS .............................................................................................................................................13 SPOTLIGHT ON HAWAIIAN BIRDS .....................................................................................................................27 Population Trends of Island Species Since Listing ................................................................................ 28 ABC’S STANCE ON THE ESA .............................................................................................................................. -

Jobos Bay Estuarine Profile a NATIONAL ESTUARINE RESEARCH RESERVE

Jobos Bay Estuarine Profile A NATIONAL ESTUARINE RESEARCH RESERVE Revised June 2008 by Angel Dieppa, Research Coordinator Ralph Field Editor Eddie N. Laboy Jorge Capellla Pedro O.Robles Carmen M. González Authors Photo credits: Cover: Cayos Caribe: Copyright by Luis Encarnación Egrets: Copyright by Pedro Oscar Robles Gumbo-limbo tree: Copyright by Eddie N. Laboy Chapter 3 photos: Copyright by Eddie Laboy JOBOS BAY ESTUARINE PROFILE: A NATIONAL ESTUARINE RESEARCH RESERVE (2002) For additional information, please contact: Jobos Bay NERR PO Box 159 Aguirre, PR 00704 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Jobos Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve is part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System, established by Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act, as amended. Additional information about this system can be obtained from the Estuarine Reserve Division, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, US Department of Commerce, 1305 East-West Highway, Silver Spring, Maryland 20910. This profile was prepared under Grants NA77OR0457 and NA17OR1252. The Jobos Bay Estuarine Profile is the culmination of a collaborative effort by a very special group of people whose knowledge and commitment made this document possible. Our most sincere gratitude is extended to all of those who contributed, directly or indirectly, to this effort. Particular appreciation goes to Dr. Eddie N. Laboy, from the Interamerican University, Dr. Jorge Capella from the Department of Marine Science, University of Puerto Rico, Mr. Ralph M. Field, and Dr. Pedro Robles, former Research Coordinator of the Reserve, for assisting in writing portions of this document. Dr. Ariel Lugo, Vicente Quevedo, Dr.