Industrial Relations for a Green Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IMPEL Water Crimes Workshop 24Th October 2018

IMPEL Water Crimes Workshop 24th October 2018 in the framework of the Conference “Protecting habitats and endangered species in Europe through tackling Environmental crime” Heraklion – Crete (Gr) 22th - 24th October, 2018 Introduction The environment provides the very foundation of sustainable development, health, food security and economies. Ecosystems provide clean water supply, clean air and secure food and ultimately both physical and mental wellbeing. Natural resources also provide livelihoods, jobs and revenues to governments that can be used for education, health care, development and sustainable business models (UNEP/INTERPOL, 2016). Particularly, water, the "blue gold" (BARLOW, 2001) – called for the first time in this way by the National Post in 1999 - is a basic essential of life and a strategic resource for the future of everyone, especially the poorest. Not only is it a vital need for human survival, groundwater has many roles in regulating the structure and functioning of healthy freshwater ecosystems (YOUNGER, 2007) and to flora and fauna. It constitutes the lifeblood of many industries, from tourism to mining, from agriculture to aquaculture. Although more than 70 % of the Earth is covered in water, 97 % is held in the oceans. Of the remaining "not salty" water (3 %), only the 2 % is freshwater locked in snow and ice (e.g. glaciers), leaving less than 1 % accessible for human requirements (US Geological Survey, 2015). Moreover, freshwater is not evenly distributed: only 9 countries share 60 % of the total amount of freshwater, and Amazonia has 15 % of the total resources but only 0.3 % of the world’s population (TOMINI, 2008). While 873 million people lack access to safe drinking water (UN, 2012), some predict that by the year 2025, 1.8 billion people will live in places and under conditions in which water is scarce" (see e.g. -

EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER the GOVERNMENT of GREECE • Follow up to Collective Complaints • Complementary Information on Article

28/08/2015 RAP/Cha/GRC/25(2015) EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER 25th National Report on the implementation of the European Social Charter submitted by THE GOVERNMENT OF GREECE Follow up to Collective Complaints Complementary information on Articles 11§2 and 13§4 (Conclusions 2013) __________ Report registered by the Secretariat on 28 August 2015 CYCLE XX-4 (2015) 25th Greek Report on the European Social Charter Follow-up to the decisions of the European Committee of Social Rights relating to Collective Complaints (2000 – 2012) Ministry of Labour, Social Security & Social Solidarity May 2015 25th Greek Report on the European Social Charter TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Collective Complaint 8/2000 “Quaker Council for European Affairs v. Greece” .......... 4 2. Collective Complaints (a) 15/2003, “European Roma Rights Centre [ERRC] v. Greece” & (b) 49/2008, “International Centre for the Legal Protection for Human Rights – [INTERIGHTS] v. Greece” ........................................................................................................ 8 3. Collective Complaint 17/2003 “World Organisation against Torture [OMCT] v. Greece” ................................................................................................................................. 12 4. Collective Complaint 30/2005 “Marangopoulos Foundation for Human Rights v. Greece” ................................................................................................................................. 19 5. Collective Complaint “General Federation of Employees of the National Electric -

Confidential1 International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) V

EUROPEAN COMMITTEE OF SOCIAL RIGHTS COMITÉ EUROPÉEN DES DROITS SOCIAUX Confidential1 International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) v. Greece Complaint No. 72/2011 REPORT TO THE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS Strasbourg, 23 January 2013 1 It is recalled that pursuant to Article 8§2 of the Protocol, this report will not be made public until after the Committee of Ministers has adopted a resolution, or no later than four months after it has been transmitted to the Committee of Ministers, namely 5 June 2013. Introduction 1. Pursuant to Article 8§2 of the Protocol providing for a system of collective complaints (“the Protocol”), the European Committee of Social Rights, a committee of independent experts of the European Social Charter (“the Committee”) transmits to the Committee of Ministers its report1 on Complaint No. 72/2011. The report contains the Committee’s decision on the merits of the complaint (adopted on 23 January 2013). The decision on admissibility (adopted on 7 December 2011) is appended. 2. The Protocol came into force on 1 July 1998. It has been ratified by Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal and Sweden. Furthermore, Bulgaria and Slovenia are also bound by this procedure pursuant to Article D of the Revised Social Charter of 1996. 3. The Committee’s procedure was based on the provisions of the Rules of 29 March 2004 which it adopted at its 201st session and revised on 12 May 2005 at its 207th session, on 20 February 2009 at its 234th session and on 10 May 2011 at its 250th session. -

Capability Statement Indicative List Of

SYBILLA Ltd. Managing Environment, Safety & Risk 16 Ypsilandou, Maroussi GR 151 22 Athens, Greece Τel +30210-8024244 / Fax +30210-6141245 VAT No. EL 095487874 CERTIFIED M.S. ISO 9001:2015 e-mail : [email protected] ISO 14001:2015 CAPABILITY STATEMENT INDICATIVE LIST OF CONCEPT, DETAILED DESIGN AND VERIFICATION REPORTS OF 1. HAZARDOUS MATERIALS AND SUBSTANCE MANAGEMENT. 2. INDOOR POLLUTION RESTORATION 3. SOIL REMEDIATION STUDIES) SEPTEMBER 2020 SYBILLA Ltd. Managing Environment, Safety & Risk 16 Ypsilandou, Maroussi GR 151 22 Athens, Greece Τel +30210-8024244 / Fax +30210-6141245 VAT No. EL 095487874 CERTIFIED M.S. ISO 9001:2015 e-mail : [email protected] ISO 14001:2015 Schinias Park A1 Zone Soil Remediation Report CONTRACTING ALEKSANDROS TECHNICAL AE FOR YPEHODE AUTHORITY CONTRACT AMOUNT CONFIDENTIAL YEAR 2004 PROJECT TYPE SOIL REMEDIATION STUDY LOCATION ATHENS SYBILLA Ltd. Managing Environment, Safety & Risk 16 Ypsilandou, Maroussi GR 151 22 Athens, Greece Τel +30210-8024244 / Fax +30210-6141245 VAT No. EL 095487874 CERTIFIED M.S. ISO 9001:2015 e-mail : [email protected] ISO 14001:2015 Environmental Restoration Study of the Thoriko Bay CHEMICAL ENGINEERING, ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT SCOPING STUDY AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY Χημικές αναλύσεις pH στερεών πολφού ( ρύποι, Ci*, +S) Ci < Όρια ΝΑΙ ΝΑΙ ΝΑΙ ποιότητας S < 0.3% 5 < pH < 8 ΑΔΡΑΝΗ εδαφών ΟΧΙ ΟΧΙ Ο ΧΙ Δοκιμές Μέτρηση δυναμικού ΝΑΙ εκχυλισιμότητας παραγωγής οξύτητας, pH < 5 ΟΞΙΝΑ ΔΠΟ ΟΧΙ ΝΑΙ Ci < όρια ΝΑΙ ΔΠΟ < όριο ΝΑΙ pH > 8 ποιότητας δοκιμής ΑΛΚΑΛΙΚΑ νερών ΟΧΙ Ο ΧΙ ΕΚΧΥΛΙΣΙΜΑ ΠΙΘΑΝΗ ΠΑΡΑΓΩΓΗ ΟΞΥΤΗΤΑΣ CONTRACTING GREEK DEMOCRACY/PREFECTURE OF ATTICA/PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT AUTHORITY CONTRACT AMOUNT 183.000 ΕURO (SYBILLA LTD 55000 ΕΥΡΩ) YEAR 2005-2010 PROJECT TYPE CHEMICAL ENGINEERING, ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT SCOPING STUDY AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY LOCATION ATHENS-THORIKO BAY LAVRIO SYBILLA Ltd. -

Complaint No 72/2011

EUROPEAN COMMITTEE OF SOCIAL RIGHTS COMITÉ EUROPÉEN DES DROITS SOCIAUX 26 July 2011 Case Document No 1 International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH) v. Greece Complaint No 72/2011 COMPLAINT Registered at Secretariat on 8 July 2011 TO THE EUROPEAN COMMITTEE OF SOCIAL RIGHTS Council of Europe, Strasbourg F r a n c e COLLECTIVE COMPLAINT lodged in accordance with the Additional Protocol of 1995 providing for a system of collective complaints and with Rules 23 and 24 of the Committee’s Rules of Procedure International Federation for Human rights (Hellenic League of Human Rights) v. Greece 8 July 2011 1 Contents I. The Parties 3 II. The main issue 4 III. Admissibility requirements 5 a. Jurisdiction ratione personae 5 b. Jurisdiction ratione temporis 6 IV. Statement of the facts 7 a. The legal framework for discharging liquid industrial waste into the River Asopos and the groundwater in the region of Oinofyta 8 b. National case-law on industrial waste 14 c. The presence of hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) in the surface water of the Asopos and in the groundwater around Oinofyta 19 d. Hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)): a highly toxic molecule for living organisms 24 e. Food safety issues 32 f. Applicable measures? 36 V. The violations of the Charter on which the complaint is based 39 a. Central government’s responsibility 41 b. The responsibility of the (former) Prefecture of Boeotia 45 c. The responsibility of the Municipality of Oinofyta 46 d. Conclusions 49 VI. Conclusion 50 VII. Declaration and signature 51 VIII. Appendices 52 - 3 - Ι. THE PARTIES Α. -

Sustainability Report 2018

SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2018 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE 04 CEO’S MESSAGE 05 ABOUT THE REPORT 06 STRIKING POINTS 08 1. ABOUT EYDAP 13 1.1 Profile of EYDAP 14 1.2 Corporate Governance 36 1.3 Value Chain 42 1.4 Supply Chain 46 1.5 Participations and Recognitions 50 2. SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 53 2.1 Dialogue with Stakeholders 54 2.2 Materiality Analysis 56 3. CREATING VALUE FOR OUR EMPLOYEES 61 3.1 Employment 62 3.2 Training and Education 69 3.3 Health & Safety of Employees 71 3.4 Human Rights in Workplace – Opportunities 78 4. CREATING VALUE FOR THE SOCIETY 81 4.1 Environmental Awareness 82 4.2 Actions of Social Solidarity & 86 Preservation of Cultural Heritage 5. CREATING VALUE FOR THE MARKET 95 5.1 Affordable Pricing- Customer Service 96 5.2 Health & Safety of Consumers: 102 Drinking Water Quality 5.3 Health & Safety of Consumers: 110 EYDAP Sewerage Services 5.4 Access to Clean Water, Sustainability of Water Resources 126 & Water Supply Coverage 5.5 Reliable Network & Water Efficiency 132 5.6 Fighting against Corruption 138 6. CREATING VALUE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT 144 6.1 Marine Environment Protection 146 (Effluent Treatment) 6.2 Environmental Compliance 150 6.3 Solid Waste Management 153 (Circular Economy) 6.4 Energy Efficiency 158 GRI TABLE of CONTENTS 160 4 ΕΥDAP GRI 102-14 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE Dear readers, 2018 Sustainability Report forcefully demonstrates EYDAP’S commitment to the principles of sustainable development and its focus on human beings, the society, and the environment. Our company, the largest in Greece in the water supply and sewerage treatment sector and one of the largest in Europe, continues to grow. -

Public Participation in Environmental Decision-Making Processes. the Asopos Case

National and Kapodistrian National and Technical University of Athens University of Athens MA ESST http://www.esst.eu Public Participation in Environmental Decision-Making Processes. The Asopos case. Maria Kontou [email protected] Thesis Supervisors: Aristotle Tympas [email protected] ([email protected]) - Greece Faidra Papanelopoulou ([email protected]) – Greece First University/Second University Graduate Program in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, NKUA/NTUA, Athens, Greece Specialization Philosophy and History of Science and Technology Year: 2011 1 Contents Acknowledgements Preface 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………....7 1.1. Aim and research questions of the study…………………………………………………….7 1.2. Public participation in decision-making processes……………………………………..10 1.3. Previous researches on environmental pollution, public health, and public participation……………………………………………………………………………………………..17 1.4. The big decision: Neutral or not?...................................................................19 1.5. Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………..20 1.6. Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………23 2. The Asopos tragedy begins. (1969-2004)………………………………………………………….24 2.1. Asopos river vs. industrial development (1969-1998)………………………………..24 2.2. The first suspicions of Boetians about the Asopos pollution. The mobilization of Oropos residents (1998-2000)……………………………………………………………….29 2.3. An expert-activist and a lay-expert working together (2000-2004)……………30 2.4. The absence of the Greek scientific community………………………………………..34 2.5. Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………..36 3. Hexavalent Chromium: from suspicions to certainty (2004-2007)……………………38 3.1. Environmental protection or economical growth? That is the question!......38 3.2. Community-based environmental movements. The ITAP example…………….43 3.3. Cancer in Oinofyta: The Asopos research in the wild………………………………….46 3.4. Non–participation. Another way to react (?)………………………………………………50 3.5. Experts express their concerns…………………………………………………………………….53 2 3.6. -

Public Participation in Environmental Decision-Making

National and Kapodistrian National and Technical University of Athens University of Athens MA ESST http://www.esst.eu Public Participation in Environmental Decision‐Making Processes. The Asopos case. Maria Kontou [email protected] Thesis Supervisors: Aristotle Tympas, Greece Graduate Program in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology NKUA / NTUA Athens, Greece Year: 2011 1 Contents Preface 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………....7 1.1. Aim and research questions of the study…………………………………………………….7 1.2. Public participation in decision‐making processes……………………………………..10 1.3. Previous researches on environmental pollution, public health, and public participation……………………………………………………………………………………………..17 1.4. The big decision: Neutral or not?...................................................................19 1.5. Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………..20 1.6. Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………23 2. The Asopos tragedy begins. (1969‐2004)………………………………………………………….24 2.1. Asopos river vs. industrial development (1969‐1998)………………………………..24 2.2. The first suspicions of Boetians about the Asopos pollution. The mobilization of Oropos residents (1998‐2000)……………………………………………………………….29 2.3. An expert‐activist and a lay‐expert working together (2000‐2004)……………30 2.4. The absence of the Greek scientific community………………………………………..34 2.5. Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………..36 3. Hexavalent Chromium: from suspicions to certainty (2004‐2007)……………………38 3.1. Environmental protection or economical growth? That is the question!......38 3.2. Community‐based environmental movements. The ITAP example…………….43 3.3. Cancer in Oinofyta: The Asopos research in the wild………………………………….46 3.4. Non–participation. Another way to react (?)………………………………………………50 3.5. Experts express their concerns…………………………………………………………………….53 3.6. Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………..55 2 4. Towards a sustainable solution (2008‐2011)……………………………………………………….57 4.1. Declassification of Asopos river. Asopos can be a river again!……………………..57 4.2. -

The Environmental Degradation of the Asopos River Basin

Anna-Maria Renner - Sustainable Development M.Sc. 2013-2015 School of Economics, Business Administration and Legal Studies INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY Studies The environmental degradation of the Asopos River Basin How can the problem be solved in an economically, environmentally and socially sustainable way? Author Anna-Maria Renner Course Sustainable Development M.Sc. Supervisor: Prof Dr Konstantinos Evangelinos Thessaloniki, 28 February 2015 Anna-Maria Renner - Sustainable Development M.Sc. 2013-2015 School of Economics, Business Administration and Legal Studies Studies Anna-Maria Renner - Sustainable Development M.Sc. 2013-2015 School of Economics, Business Administration and Legal Studies Studies Declaration I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work; I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. © 28 February 2015, Anna-Maria Renner, ID number: 1105130009 No part of this dissertation may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without the author’s prior permission. February 2015 Thessaloniki - Greece Anna-Maria Renner - Sustainable Development M.Sc. 2013-2015 School of Economics, Business Administration and Legal Studies Studies Anna-Maria Renner - Sustainable Development M.Sc. 2013-2015 School of Economics, Business Administration and Legal Studies The envStudiesironmental degradation of the Asopos River Basin How can the problem be solved in an economically, environmentally and socially sustainable way? Content i. Table of abbreviations -

Informal Industrial Ζone of Oinofyta

Greek Case Study: Informal industrial Ζone of Oinofyta Project financed by Europen Union 1 PRESENTATION (IDENTITY CARD OF SIGNIFICANT STUDY) . Name of significant study “Informal industrial zone of Oinofyta”, Beotia region. Short description The case was selected as a meaningful “case study” within the project, because it highlights a serious conflicting situation between industrial development, jobs in polluting plants, the environment and the local communities. The informal industrial zone of Oinofyta is the largest industrial concentration in central Greece; what makes it significant is the lack of planning whatsoever in the area, the uncontrolled growth and the resulting pollution of Asopos River which crosses the region. In this case, the efforts focus on: the obligation by law of the existing plants to adopt innovating anti-polluting industrial processes in order to stop further pollution, the creation of the necessary waste treatment facilities, the conservation of job places along with the clean-up of the area, the protection of Occupational Health and Safety of workers and the improvement of locals’ health conditions. It’s all about a multi-task and challenging target for both state and social partners (employers, trade unions), and local civil associations. Geographic, territorial, sectorial localization, The Zone is located at the Oinofyta - Schimatari - Tanagra area in the Beotia region, bordering Attica. More than 1.000 plants are located at the zone. Period of activity The creation of the zone began about 45 years ago in 1969; in the mid of 80s the industrial zone of Oinofyta experienced the biggest boom with more than 300 factories and 60,000 employees, and over the years the growth has continued. -

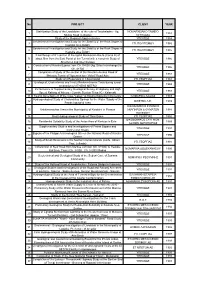

No PROJECT CLIENT YEAR 1 Stabilization Study of The

No PROJECT CLIENT YEAR Stabilization Study of the Landslides of the cuts of Tsoukalades - Ag. ΝΟΜΑΡΧΕΙΑΚΟ ΤΑΜΕΙΟ 1 1984 Nikitas Road (Lefkada) ΛΕΥΚΑΔΑΣ 2 Study of the Regional Aigaleo Avenue ΥΠΕΧΩΔΕ 1984 Geotechnical Investigation and Study for the Stability of the Rock Slopes of 3 ΥΠ. ΠΟΛΙΤΙΣΜΟΥ 1985 Kastalia area Delphi Geotechnical Investigation and Study for the Stability of the Rock Slopes of 4 ΥΠ. ΠΟΛΙΤΙΣΜΟΥ 1985 Kastalia area Delphi Final Design of B1 section of the Uphill Malakasion Route (Corse B) of 5 about 5km from the East Portal of the Tunnel with a complete Study of ΥΠΕΧΩΔΕ 1986 Structures and Interchanges Construction of Kavala Bypass from Ch. 0+600 (Ag. Sillas Interchange) to 6 ΥΠΕΧΩΔΕ 1986 Ch. 4+700 Completion of Study of the section of the Western Access Road of 7 ΥΠΕΧΩΔΕ 1988 Metsovo Tunnel of "Igoumenitsa - Volos" Road Axis 8 Study of 4 Reservoirs in Chios Island ΥΠ. ΓΕΩΡΓΙΑΣ 1988 Geological, Geotechnical and In-situ Rockmechanics Tests during tunnel 9 ΥΠΕΧΩΔΕ 1988 excavation of ATHENS METRO Performance of Supplementary Geological Survey of Highway and High 10 ΥΠΕΧΩΔΕ 1988 Speed Railway of Athens - Corinth. Section Thiva I/C - Kalamaki 11 Tourist Development of the Cave "Lakes" at Kastria Kalavrita Community ΝΟΜΑΡΧΙΑ ΑΧΑΙΑΣ 1989 Hydrogeological Study of Chalandritsa Springs for the Water Supply of the 12 ΒΙΠΕΤΒΑ Α.Ε. 1989 Patras Industrial Area ΟΙΚΟΔΟΜΙΚΟΣ ΣΥΝ/ΜΟΣ 13 Kokkinovrachos Area in the Municipality of Keratsini in Piraeus ΑΝΑΠΗΡΩΝ & ΘΥΜΑΤΩΝ 1988 ΠΟΛΕΜΟΥ 14 Final Hydrogeological Study of Thiva Basin ΥΠ. ΓΕΩΡΓΙΑΣ 1992 ΟΙΚΟΔΟΜΙΚΟΣ ΣΥΝ. ΜΟΝ. 15 Residential Suitability Study of the Aetos Area of Karistos in Evia 1989 ΑΞ/ΚΩΝ ΑΕΡΟΠΟΡΙΑΣ Supplementary Studies and Investigations of Patras Bypass and 16 ΥΠΕΧΩΔΕ 1994 Connection Roads Bypass of the Philippi Archaeological Site on the National Road of Kavala - 17 ΥΠΕΧΩΔΕ 1990 Drama Study of Small Reservoirs in the Northern Ionian Islands (Corfu, Othoni, 18 ΥΠ. -

Water Resources Management Sustaining Socio- Economic Welfare

Global Issues in Water Policy 7 Phoebe Koundouri Nikos A. Papandreou Editors Water Resources Management Sustaining Socio- Economic Welfare The Implementation of the European Water Framework Directive in Asopos River Basin in Greece Water Resources Management Sustaining Socio- Economic Welfare GLOBAL ISSUES IN WATER POLICY VOLUME 7 Editor-in-chief Ariel Dinar Series Editors José Albiac Eric D. Mungatana Víctor Pochat Rathinasamy Maria Saleth For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/8877 Phoebe Koundouri • Nikos A. Papandreou Editors Water Resources Management Sustaining Socio-Economic Welfare The Implementation of the European Water Framework Directive in Asopos River Basin in Greece Editors Phoebe Koundouri Nikos A. Papandreou Department of International and European Andreas G. Papandreou Foundation Economic Studies (DIEES) Athens , Greece Athens University of Economics and Business Athens , Greece Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment London School of Economics and Political Science London , UK ISSN 2211-0631 ISSN 2211-0658 (electronic) ISBN 978-94-007-7635-7 ISBN 978-94-007-7636-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-7636-4 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013954372 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work.