Churches in the Book of Llandaff, and the Landscape. Timothy E. Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monmouthshire Local Development Plan (Ldp) Proposed Rural Housing

MONMOUTHSHIRE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN (LDP) PROPOSED RURAL HOUSING ALLOCATIONS CONSULTATION DRAFT JUNE 2010 CONTENTS A. Introduction. 1. Background 2. Preferred Strategy Rural Housing Policy 3. Village Development Boundaries 4. Approach to Village Categorisation and Site Identification B. Rural Secondary Settlements 1. Usk 2. Raglan 3. Penperlleni/Goetre C. Main Villages 1. Caerwent 2. Cross Ash 3. Devauden 4. Dingestow 5. Grosmont 6. Little Mill 7. Llanarth 8. Llandewi Rhydderch 9. Llandogo 10. Llanellen 11. Llangybi 12. Llanishen 13. Llanover 14. Llanvair Discoed 15. Llanvair Kilgeddin 16. Llanvapley 17. Mathern 18. Mitchell Troy 19. Penallt 20. Pwllmeyric 21. Shirenewton/Mynyddbach 22. St. Arvans 23. The Bryn 24. Tintern 25. Trellech 26. Werngifford/Pandy D. Minor Villages (UDP Policy H4). 1. Bettws Newydd 2. Broadstone/Catbrook 3. Brynygwenin 4. Coed-y-Paen 5. Crick 6. Cuckoo’s Row 7. Great Oak 8. Gwehelog 9. Llandegveth 10. Llandenny 11. Llangattock Llingoed 12. Llangwm 13. Llansoy 14. Llantillio Crossenny 15. Llantrisant 16. Llanvetherine 17. Maypole/St Maughans Green 18. Penpergwm 19. Pen-y-Clawdd 20. The Narth 21. Tredunnock A. INTRODUCTION. 1. BACKGROUND The Monmouthshire Local Development Plan (LDP) Preferred Strategy was issued for consultation for a six week period from 4 June 2009 to 17 July 2009. The results of this consultation were reported to Council in January 2010 and the Report of Consultation was issued for public comment for a further consultation period from 19 February 2010 to 19 March 2010. The present report on Proposed Rural Housing Allocations is intended to form the basis for a further informal consultation to assist the Council in moving forward from the LDP Preferred Strategy to the Deposit LDP. -

Cyngor Sir Fynwy/ Monmouthshire County Council Rhestr Wythnosol Ceisiadau Cynllunio a Benderfynwyd/ Weekly List of Determined P

Cyngor Sir Fynwy/ Monmouthshire County Council Rhestr Wythnosol Ceisiadau Cynllunio a Benderfynwyd/ Weekly List of Determined Planning Applications Wythnos / Week 07.11.2018 i/to 14.11.2018 Dyddiad Argraffu / Print Date 15.11.2018 Mae’r Cyngor yn croesawu gohebiaeth yn Gymraeg, Saesneg neu yn y ddwy iaith. Byddwn yn cyfathrebu â chi yn ôl eich dewis. Ni fydd gohebu yn Gymraeg yn arwain at oedi. The Council welcomes correspondence in English or Welsh or both, and will respond to you according to your preference. Corresponding in Welsh will not lead to delay. Ward/ Ward Rhif Cais/ Disgrifia d o'r Cyfeiriad Safle/ Penderfynia Dyddiad y Lefel Penderfyniad/ Application Datblygiad/ Site Address d/ Penderfyniad/ Decision Level Number Development Decision Decision Date Description Llanfoist DM/2018/01557 Proposed rear sunroom, 21 Company Farm Approve 07.11.2018 Delegated Officer Fawr width 4.4m, projection Drive 4m, hgt to eaves 2.4m, Llanfoist Plwyf/ Parish: hgt to ridge 3.3m. Abergavenny Llanfoist Fawr Monmouthshire Community NP7 9QA Council Priory DM/2018/00467 Provision of a new library Abergavenny Town Approve 07.11.2018 Delegated Officer hub on the first floor. Hall Plwyf/ Parish: Internal alterations and Abergavenny Town Abergavenny new rooftop plant deck. And Market Hall Town Council Cross Street Abergavenny Monmouthshire Llantilio DC/2018/00205 Retention of material Land Adjacent Ty Refuse 12.11.2018 Delegated Officer Crossenny change of use of land to Coedwr a one family traveller B4521, Pont Gilbert Plwyf/ Parish: site, including the To Hill House Llantilio stationing of 1 caravan, Llanvetherine Crossenny day room, full drainage, Monmouthshire Community fencing and accessed Council driveway at land north east of Llanvetherine, Monmouthshire. -

Cadw/Icomos Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in Wales

CADW/ICOMOS REGISTER OF PARKS AND GARDENS OF SPECIAL HISTORIC INTEREST IN WALES SITE DOSSIER SITE NAME Moynes Court REF. NO. PGW (Gt) 34 OS MAP l62 GRID REF. ST 520909 FORMER COUNTY Gwent UNITARY AUTHORITY Monmouth B.C. COMMUNITY COUNCIL Mathern DESIGNATIONS Listed building: Moynes Court Grade II* Gatehouse at Moynes Court: II National Park AONB SSSI NNR ESA GAM SAM CA (Mathern) SITE EVALUATION Grade II Primary reasons for grading Survival of structure of Tudor walled garden, with medieval fishpond TYPE OF SITE walled garden; fishpond MAIN PHASES OF CONSTRUCTION l6th century VISITED BY/DATE Elisabeth Whittle/May l991 HOUSE Name Moynes Court Grid ref ST 520909 Date/style l6th century/Tudor Brief description Moynes Court is a three-storey stone house situated on a slight ridge to the E of St Pierre Park, SW of Chepstow. It is of medieval origin, first mentioned in a survey of Wentwood of l27l, which mentioned Bogo de Knovill as the owner of a mansion here. In l307 an Inquisition Post Mortem listed a capital messuage with a garden and pigeon house, worth 20s a year. The house was largely rebuilt, probably by the Morgan family in the late l6th century, with a symmetrical facade on the SE side. The core of the house is probably older, and the very tall gatehouse to the SE certainly is; it is thought to be late l3th- century in date. In l608 Bishop Godwin of Llandaff bought Moynes Court, and there is a heraldic panel over the front door with his coat of arms and the date l609. -

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY March 2019

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY March 2019 Volume 1 Strategic Framework Monmouth CONTENTS Key messages 1 Setting the Scene 1 2 The GIGreen Approach Infrastructure in Monmouthshire Approach 9 3 3 EmbeddingGreen Infrastructure GI into Development Strategy 25 4 PoSettlementtential GI Green Requirements Infrastructure for Key Networks Growth Locations 51 Appendices AppendicesA Acknowledgements A B SGISources Database of Advice BC GIStakeholder Case Studies Consultation Record CD InformationStrategic GI Networkfrom Evidence Assessment: Base Studies | Abergavenny/Llanfoist D InformationD1 - GI Assets fr Auditom Evidence Base Studies | Monmouth E InformationD2 - Ecosystem from Services Evidence Assessment Base Studies | Chepstow F InformationD3 - GI Needs fr &om Opportunities Evidence Base Assessment Studies | Severnside Settlements GE AcknowledgementsPlanning Policy Wales - Green Infrastructure Policy This document is hyperlinked F Monmouthshire Wellbeing Plan Extract – Objective 3 G Sources of Advice H Biodiversity & Ecosystem Resilience Forward Plan Objectives 11128301-GIS-Vol1-F-2019-03 Key Messages Green Infrastructure Vision for Monmouthshire • Planning Policy Wales defines Green Infrastructure as 'the network of natural Monmouthshire has a well-connected multifunctional green and semi-natural features, green spaces, rivers and lakes that intersperse and infrastructure network comprising high quality green spaces and connect places' (such as towns and villages). links that offer many benefits for people and wildlife. • This Green Infrastructure -

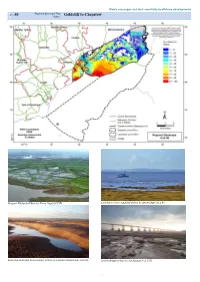

Goldcliff to Chepstow Name

Welsh seascapes and their sensitivity to offshore developments No: 50 Regional Seascape Unit Goldcliff to Chepstow Name: Newport Wetlands (Photo by Kevin Dupé,©CCW) Looking across to England (Photo by Kevin Dupé,©CCW) Extensive sand flats in the estuary (Photo by Charles Lindenbaum ©CCW) Severn Bridge (Photo by Ian Saunders ©CCW) 1 Welsh seascapes and their sensitivity to offshore developments No: 50 Regional Seascape Unit Goldcliff to Chepstow Name: Seascape Types: TSLR Key Characteristics A relatively linear, reclaimed coastline with grass bund sea defences and extensive sand and mud exposed at low tide. An extensive, flat hinterland (Gwent Levels), with pastoral and arable fields up to the coastal edge. The M4 and M48 on the two Severn bridges visually dominate the area and power lines are also another major feature. Settlement is generally set back from the coast including Chepstow and Caldicot with very few houses directly adjacent, except at Sudbrook. The Severn Estuary has a strong lateral flow, a very high tidal range, is opaque with suspended solids and is a treacherous stretch of water. The estuary is a designated SSSI, with extensive inland tracts of considerable ecological variety. Views from the coastal path on bund, country park at Black Rock and the M4 and M48 roads are all important. Road views are important as the gateway views to Wales. All views include the English coast as a backdrop. Key cultural associations: Gwent Levels reclaimed landscape, extensive historic landscape and SSSIs, Severn Bridges and road and rail communications corridor. Physical Geology Triassic rocks with limited sandstone in evidence around Sudbrook. -

Welsh Bulletin

BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF THE BRITISH ISLES WELSH BULLETIN Editor: R. D. Pryce No. 66, WINTER 1999 Lavatera arborea- one of the earliest flowering plants recorded from v.c. 35 (see p.19). (lllustration from Sowerby's 'English Botany') 2 Contents CONTENTS Editorial .......................................................................................................................3 Annual General Meeting, 1999 ................................................................................... 5 Chairman's Report ........................................................................................... 5 Hon. Secretary's Report ................................................................................... 5 Hon. Treasurer's Report ................................................................................... 6 Elections ..........................................................................................................6 Committee for Wales, 1999-2000 ....................................................................6 Any other business .......................................................................................... 7 38th Welsh Annual General Meeting and18th Exhibition Meeting, 2000 .................... 8 Welsh Field Meetings - 2000 ................................................................................... 1 0 Epilobium x obscurescens Kitchener & McKean new to Wales ................................ 13 Rhinanthus angustifolius C. C. Gmel., Greater Yellow-rattle recorded in error for Wales ............................................................................................................ -

Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1958-59

ADRODDIAD BLYNYDDOL / ANNUAL REPORT 1958-59 WINIFRED COOMBE TENNANT (`MAM O NEDD') Ffynhonnell / Source The late Mrs Winifred Coombe Tennant ('Mam o Nedd'), London. Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1958-59 Disgrifiad / Description A collection of manuscripts, press cuttings, printed books, and photographs relating mainly to 'Gorsedd y Beirdd' and to the National Eisteddfod of Wales, covering 1917-55. There are a large number of letters to and from Mrs. Coombe Tennant (who was initiated as an Honorary Member of the Gorsedd in 1918, promoted to full membership in 1923, and given the official title of 'Mistress of the Robes' in 1928) relating mainly to matters concerned with the Gorsedd Robes and Regalia and to the Gorsedd Ceremony. There are also letters in connection with various Eisteddfodau, particularly the Arts and Crafts sections, and a group of letters, etc., relating to the initiation of HRH Princess Elizabeth as a member of the Gorsedd at Mountain Ash Eisteddfod, 1946. The manuscripts and papers include memoranda, notes and reports of the Bardic Robes Committee, 1922- 52; minutes of 'Bwrdd Gweinyddol yr Orsedd', 1923-44, and of 'Bwrdd yr Orsedd', 1938-54; articles by Mrs. Coombe Tennant entitled 'A Chapter of Gorsedd History', 'Vanishing Beauty', and 'Beautiful Things made in Wales', 1928-50; and an article on 'Gorsedd y Beirdd' by A. E. Jones ('Cynan'). The printed material includes Gorsedd Proclamation programmes, 1917-54, programmes of Gorsedd meetings, 1925-51, lists of officers and members of the Gorsedd, 1923-49, 1924-59, 1947, annual reports of the Eisteddfod Council, 1937-50, Eisteddfod programmes, 1917-52, and copies of Eisteddfod y Cymry by Dr. -

Notice of Poll

NOTICE OF POLL & SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS HYSYBSIAD O BLEIDLEISIO & LLEOLIAD GORSAFOEDD PLEIDLEISIO Local Authority Name: Monmouthshire County Council Enw’r awdurdod lleol: Cyngor Sir Fynwy Name of ward/area: Abergavenny (Cantref) Enw’r ward/adran: Number of councillors to be elected in the ward/area: 3 Nefer y ceynghorwyr i’w hetol yn y ward adran hon: A poll will be held on 4 May 2017 between 7am and 10pm in this ward/area Cynhelir yr etholiad ar 4 Mai 2017 rhwng 7yb a 10yh yn y ward/adran hon The following people stand nominated for election to this ward/area Mae’r bobl a ganlyn wedi’u henwebu I sefyll i’w hethol Names of Signatories Name of Description (if Home Address Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Candidate any) Assentors CLOUTH 4 Mount Street, Welsh Labour Janet P Simcock (+) David R Simcock (++) Alan David Abergavenny, Candidate/Ymgeisydd NP7 7DT Llafur Cymru COPNER 1A Stanhope Street, Independent Brynley Price (+) Paul Nutall (++) Christopher James Abergavenny, NP7 7DH DODD 18 Trinity Street, Welsh Conservative Heather S Woodhouse (+) Christopher D Woodhouse Samantha Jane Abergavenny, Party Candidate (++) Monmouthshire, NP7 5EA MORGAN Clydach House, Welsh Conservative Henry D Yendoll (+) Mary R Yendoll (++) Fred Saleyard, Party Candidate Abergavenny, Mons, NP7 0HD SIMCOCK 26 Mount Street, Welsh Labour Janet P Simcock (+) David J Marshall (++) David Richard Abergavenny, Candidate/Ymgeisydd NP7 7DT Llafur Cymru The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Mae lleoliadau’r Gorsafoedd Pleidleisio a disgrifiad o’r bobl sydd â hawl i bleidleisio yno fel y canlyn: No. -

Cyngor Sir Fynwy / Monmouthshire County Council Rhestr Wythnosol

Cyngor Sir Fynwy / Monmouthshire County Council Rhestr Wythnosol Ceisiadau Cynllunio a Gofrestrwyd / Weekly List of Registered Planning Applications Wythnos / Week 25.07.18 i/to 31.07.18 Dyddiad Argraffu / Print Date 31.07.2018 Mae’r Cyngor yn croesaw u gohebiaeth yn Gymraeg, Saesneg neu yn y ddw y iaith. Byddw n yn cyfathrebu â chi yn ôl eich dew is. Ni fydd gohebu yn Gymraeg yn arw ain at oedi. The Council w elcomes correspondence in English or Welsh or both, and w ill respond to you according to your preference. Corres ponding in Welsh w ill not lead to delay. Ward/ Ward Rhif Cais/ Disgrifia d o'r Cyfeiriad Safle/ Enw a Chyfeiriad yr Enw a Chyfeiriad Math Cais/ Dwyrain/ Application Datblygiad/ Site Address Ymgeisydd/ yr Asiant/ Application Gogledd Number Development Applicant Name & Agent Name & Type Easting/ Description Address Address Northing Shirenewton DC/2017/01143 To save the 16th St Pierre Hotel And Marriott St Pierre Listed 351515 century ornate Country Club Hotel Tony Brown Building 190471 Plwyf/ Parish: Dyddiad App. Dilys/ pastel ceiling from St Peters Church St Pierre Park St Pierre Park Consent Mathern Date App. Valid: possible Road Chepstow Chepstow Heritage Community 14.06.2018 catastrophic Mathern Monmouthshire Monmouthshire Council damage. (Support Monmouthshire NP16 6YA NP16 6YA to the original NP16 6YA floor above and ceiling below). Drybridge DC/2017/01448 Demolition of Briardene Mr Robert Stone Planning 350054 Existing dormer 18 Rockfield Road C/O Agent Mr David Morley Permission 213018 Plwyf/ Parish: Dyddiad App. Dilys/ bungalow and Monmouth D.G.M Architects Monmouth Date App. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-58131-8 - Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales 1300–1500: Volume II: East Anglia, Central England, and Wales Anthony Emery Index More information index Bedingfield, Sir Thomas 11 Bonde, Nicholas 21 Broads, The, 17 n9 Bedingfield Hall 25 Bonville, William, Lord (d. 1461) 193 Broadway, Grange House 460 Bedwell Park 176 Bonville’s Castle 655 Brockley Hall 24 Beeleigh Abbey 30 Booth, William, bishop of Lichfield (d. 1464) Brome, John 337, 343, 360–1 INDEX Beeston Castle 476 409 Brome, moated site 32 Bek, Thomas, bishop of St David’s (d. 1293) Boothby Pagnell Manor House 178, 179, 189 Bromfield and Yale, lordship, 618, 619 643, 647 n10 n4, 262 Bromholm Priory 15, 29, 143 n8 Belknap, Sir Edward 337 Bordesley Abbey 41 Broncoed Tower 656–7, 685 Belleau Manor House 181, 221–2 Boreham, bishop’s house 503 Broncroft Castle 474, 479, 522–3 Belliers, Sir James 182 Bosbury, Old Court 480, 512–15 Bronllys Castle 610, 616, 702 Belsay Castle 349, 363 Boston Bronsil Castle 334, 479, 523–5, 601 Belstead Hall 25, 122 n15 Guildhall 189 n16, 224, 375 Brooke Priory 182 Belvoir Castle 172, 189 n11, 195, 215, 218, 384, Hussey Tower 180, 223–4, 352 Broomshaw Bury 166 391 Rochford Tower 180, 224–5, 352 Brotherton, Thomas, earl of Norfolk (d. 1338) Bengeworth Castle 334 St Botolph’s Church 311 20 Detailed descriptions are given in bold type. Readers should also check for additional references on any given page. Benington, Richard 224 Boteler famile of Sudeley 335, 495 Broun, John 477 Bentley Hall 34 n60, 102 Boteler, Sir Ralph 278–9, 327, 352 Brown, Lancelot, ‘Capability’ (d. -

84Mm X 120Mm

PLANNING NOTICE HYSBYSIAD CYNLLUNIO . Development Affecting The Setting Of A Listed Building And/Or The Character or Appearance of a Conservation Area Datblygiad yn Effeithio ar Osodiad Adeilad Rhestredig a/neu Gymeriad neu Ymddangosiad Ardal Gadwraeth Application No.: DM/2018/01058 Variation of condition 1 (DC/2008/00156) to extend the time allowed to commence development. 2 Model Cottages, Monmouth Road, UskNP15 2LB. Listed Building Consent Caniatâd Adeilad Rhestredig Application No.: DC/2017/01143 To save the 16th century ornate pastel ceiling from possible catastrophic damage. (Support to original floor). Marriott St Pierre Hotel, Chepstow NP16 6YA. Application No.: DM/2018/00457 Conversion of outbuilding to two holiday lets. The Mardy Farm, Llandenny Road, Usk NP15 1DN. Application No.: DM/2018/01069 Replacement of front door from timber to metal frame. Replacement of section of masonry to upper level of one of the original large threshing door openings with timber- framed glazing, which would be an extension of the existing ground floor timber-framed glazing. See concurrent planning DM/2018/01068. West Tithe Barn, Moynes Court, Mathern NP16 6HZ. Application No.: DM/2018/01117 Replacement roof covering to existing porch. 32 Monk Street, Abergavenny Monmouthshire. Application No.: DM/2018/01129 Conversion of stables to provide detached dwelling. The Stable Adjoining St Marys Church, Usk. Application No.: DM/2018/01137 Amendments to approved drawings for conversion of Pen Y Fal Chapel (DC/2015/00245 & DC/2015/00246). Pen Y Fal Chapel, Abergavenny NP7 5LX. Application No.: DM/2018/01140 Replacement windows to the front elevation ground floor, new railings to the frontage, new French doors to rear elevation, and new disabled toilet internally. -

Medieval General Towns

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Select Bibliography, Southeast Wales Medieval A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Southeast Wales – Medieval, bibliography 22/12/2003 General Pugh TB (ed) 1971 Glamorgan Country History Vol III The Middle Ages Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales Glamorgan Inventory Howell R 1988 The History of Gwent Rees W 1953 A Survey of the Duchy of Lancaster Lordships in Wales 1609-1613 Courtney P 1994 Medieval and Later Usk Cardiff Griffiths, M 1988 Native society on the Anglo- Norman frontier: the Evidence of the Margam Charters Welsh Hist Rev 12 (2), 179-216 Evans C J O 1954 Monmouthshire: its history and topography Cardiff Driscoll EM 1958 The denudation chronology of the Vale of Glamorgan T&P Inst Br G 25, 45-47 Jones A 1955 The Story of Glamorgan Llandebie Williams A G 1991 ‘The Norman Lordship of Glamorgan: an examination of its establishment and development’ Unpublished Mphil thesis, University of Wales, Cardiff Towns Town Archaeological Research Historical research General Soulsby I 1983 The Towns of Medieval Wales Carter H 1966 The Towns of Wales Griffiths RA Boroughs of Medieval Wales Courtney P 1988 The Marcher town in medieval Gwent: a study in regional history Scott Archaeol Rev 5 (1-2), 103-10 Penrose R 1997 Urban Development in the Lordships of Glamorgan, Gwynllwg, Caerleon and Usk under the de Clare family 1217-1314 unpublished Phd thesis University of Wales Aberavon Davies L 1914 Outlines of the History of the Aberavon District O’Brien J 1926 Old Afan and Margam Abergavenny Radcliffe F & Knight JK 1969 Olding F Abergavenny: A Excavations at Abergavenny Historic Landscape 1962-69: Medieval and Courtney P 1994 Medieval Kater Monmouthshire Antiq and Later Usk 2, 65-103 Ashmore PJ & FM 1973 Excavations at Abergavenny Orchard Site 1972 Monmouthshire Antiq 3, 104-110 Bridgend Randall HJ 1955 Bridgend, The story of a Market Town Newport This document’s copyright is held by contributors and sponsors of the Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales.