Rupert Clark - Chairman & Treasurer Peter Cole - Secretary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of people who have shaped British history, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Oxford DNB (ODNB) currently includes the life stories of over 60,000 men and women who died in or before 2017. Over 1,300 of those lives contain references to Coventry, whether of events, offices, institutions, people, places, or sources preserved there. Of these, over 160 men and women in ODNB were either born, baptized, educated, died, or buried there. Many more, of course, spent periods of their life in Coventry and left their mark on the city’s history and its built environment. This survey brings together over 300 lives in ODNB connected with Coventry, ranging over ten centuries, extracted using the advanced search ‘life event’ and ‘full text’ features on the online site (www.oxforddnb.com). The same search functions can be used to explore the biographical histories of other places in the Coventry region: Kenilworth produces references in 229 articles, including 44 key life events; Leamington, 235 and 95; and Nuneaton, 69 and 17, for example. Most public libraries across the UK subscribe to ODNB, which means that the complete dictionary can be accessed for free via a local library. Libraries also offer 'remote access' which makes it possible to log in at any time at home (or anywhere that has internet access). Elsewhere, the ODNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. Early benefactors: Godgifu [Godiva] and Leofric The benefactors of Coventry before the Norman conquest, Godgifu [Godiva] (d. -

Notes and References

Notes and References Chapter 1 1. This view underlies the Cycle of Deprivation Studies which were set up jointly between the Department of Health and Social Services and the Social Sciences Research Council, encouraged by the Secretary of State for social services, Sir Keith Joseph, in 1972. 2. This view underlies the Six Towns Studies set up by the Department of the Environment in 1973 and the Comprehensive Community Programmes set up by the Home Office in 1974. 3. This is the standard pluralist view underlying most liberal academic treatments of the poverty 'problem'. 4. With Liverpool, the Coventry Community Development Project was the first of the twelve Community Development Projects set up by the Home Office from 1969. The Coventry project submitted its final report, which contained a summary of the Coventry Industry - Hillfields study, in March 1975. 5. The Marxian critique of neo-classical economic theory is now well known. As it does not add to the analysis developed in this book it will not be repeated here. Those interested may look at Rowthorn [1974] or Hollis and Nell [1975] for recent contributions to that critique. 6. For an interesting explanation of this lack of concreteness in most Marxist analysis during the past fifty years, see Anderson, [1976]. Chapter 2 1. 'In broad outline, the Asiatic, ancient, feudal and modern bourgeois [capitalist] modes of production may be designated as epochs marking progress in the economic development of society.' (A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, p. 21.) Note that all Marx's writings will be cited by title alone, rather than author and date of publication as for other writers. -

DEC 2020 / Jan 2021

Founded 1967 There have definitely been a few silent nights for the club this year but, hopefully, we will be back to Hark the Herald by spring. Newsletter of the Traditional Car Club of Doncaster December 2020/January 2021 Email special due to Covid 19 virus 1 Editorial Hello again, I hope that I find you all safe and well, even if a bit restricted. The review of this last year won’t take long, I’ve not done much or been anywhere much but am still here so it’s not all bad. If the vaccine roll out works better than some other things, the prediction is some return to ‘normal’ by East- er. Must admit that I see a conflict between normal and our club but I know what they mean. Spring is the time that we really start to get going with Breakfast meetings, Drive it day and show plan- ning can really pick up so we may be back in full flow at our usual time, we will see. A reminder that the committee is proposing to carry over subs to 2021 as we were effectively shut for most of this year. We have found a way to carry on with Tradsheet and our members only Facebook page has kept us informed and entertained. The website has been running throughout and has visitors from all over the world looking to see what we are up to. In that respect, we have carried on as best we can and have fared better than some clubs that have all but disappeared for the time being. -

N.Z. Veteran and Vintage Motoring

\ . EADED IIEELS N.Z. VETERAN AND VINTAGE MOTORING DECEMBER, 1961 ., . ) t , • f) Rnli \-RO'r FTn "Wizard" Smith Tries Out Car On Beach Above : "Wizard Smith and Don Hark ness tryout hu ge car prior to World Rec ord lO-mile run. B elow : Mr. Smith. and a view of his ra cing car from the rear show ing the F ir estone Tires which he used in making the A us tralian record. lVIEMORIES OF THE PAST N. (WIZARD) SMITH SETS WORLD'S SPEED MARK IN NEW ZEALAND FIRESTONE EQUIPPED CAR LOWERS IO-MILE RE CORD; I-MILE NEXT Ma intaining th e terrific speed a verage of mil es per hour, by averaging 128 m.p .h . wit h a 148.637 mil es per hou r to cove r a ten-mile maximum speed of 142 m.p.h. st retc h in 4.02 1-5, Mr Norma n (Wiza rd) Follow ing th e exa mple of champion drivers Smith, well-known Au stral ian mot or enthus i in Am erica a nd else whe re in th e world, Smi th ast, smashe d the world's ten-mile sp eed record equipped his ca r with Firestone "Gu m-D ippe d" on January 17, at N in ety Mil e Beach , Ka ita ia, tyres, ari d F iresto ne equipment perfor med per Ne w Zealand. f ectly in mak ing both records. F or the Aus The fo rme r record , accordi ng to availa ble t ralian run, F irestone t yres were f urnishe d by figures, wa s 148- 409 mil es per hou r, es ta b Mr E. -

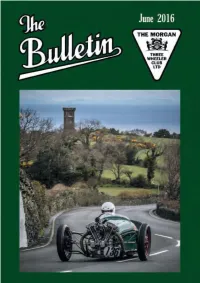

MTWC-Bulletin-June-2016.Protected

Happenings in June - too many to fit in this month but all events appear after the respective group report …. So here is a photo instead: Without prompting, Harriet Sermon picked up The Bulletin to read. Clare said she insisted on taking it to bed .. Photo: Clare Sermon COVER: Tracy Cameron - Hale Morgan now owned by Kurt Engelhorn … Kurt and Tracy were sharing the car which is prepared by Ewan Cameron. Contents: 14 Letters and Emails 30 Group Reports 3 Editorial Eyewash 15 Imprinting 39 Registry Adrian M-L’s Conrod / 18 Red … The First /New Forest Group Mag re-magnetised Supercharged Morgan 42 Homer’s Odessey 5 Goggles and Gauntlets 44 Floggery 6 Opening Run Page 48 Salome and Salote 8 Book Launch 22 New Wings for Old July more of the same stuff 10 Competition report / 23 12 VSCC Curborough 24 13 Training Day 26 Norfolk W/end Advert 2 Vol. 71 June 2016 No. 6 THE BULLETIN AFFILIATED TO THE ACU: NON - TERRITORIAL CLUB WEBSITE: www.mtwc.co.uk Editorial One of the downsides of being an editor is but I have always found the DVLA very helpful … I have always been very polite - looking at the layout, the typeface, colours as I would hope to be treated myself. We are … and the inevitable errors - whether fortunate in having, through the Registrar, typographical or factual. In a similar vein, who is a consummate diplomat) a good after looking at The Bulletin on screen for working relationship with the DVLA – much hours on end, lining up and arranging the to the benefit of members. -

PDF Download the Horbick Motor Car Kindle

THE HORBICK MOTOR CAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Derek Mathews | 76 pages | 22 Feb 2018 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781985021280 | English | none The Horbick Motor Car PDF Book Holbrook Lane, Coventry , United Kingdom. The executi ve committee have decided to recommend that the invitation from Llanelly be accepted and this will pro- bably be confirmed at a meeting of the general committee to be held on Mon- day. HELP 3 6. Many of the cabs use diesel, and drivers had initially complained about clean-air restrictions. We think it is a Bedford with a Holden type body. The car on right is also relatively unusual being a cca Charron. Nathan Griffiths expressed his pleasure at the project. Magistrate Were you drunk? Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Brodie conducted an inquest at Cwmbach on Wednesday on the body of David Emlyn Evans, a child of 4, who died on Tuesday. The Times , Friday, Dec 01, ; pg. Views Read View source View history. Not much known about the underside. Companies and marques. The dividend cheques of the Stepney Wheel were sent out this week. If we don't have it in stock, use our Car Finder service and we'll find it for you. This bike was used extensively in WW1 as the standard dispatch rider's machine. Quite a few chassis were exported to Britain and full cars were also eventually made in Britain. There has been a great rush for tickets, but there are still plenty of good seats for each night at present. Rees presided over a large gathering. -

Coventry's Armaments and Munitions Industry 1914-1918 Batchelor, L.A

A Great munitions centre: Coventry's armaments and munitions industry 1914-1918 Batchelor, L.A. Submitted version deposited in CURVE March 2011 Original citation: Batchelor, L.A. (2008) A Great munitions centre: Coventry's armaments and munitions industry 1914-1918. Unpublished MScR Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. A number of images, maps and tables have been removed for copyright reasons. The unabridged version of the thesis can be viewed at the Lanchester Library, Coventry University. CURVE is the Institutional Repository for Coventry University http://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open A GREAT MUNITIONS CENTRE: COVENTRY’S ARMAMENTS & MUNITIONS INDUSTRY 1914 – 1918 Laurence Anthony Batchelor “We see new factories arise; we see aeroplanes in the air. The workshops have been industrial beehives all the time and Coventry has developed as a great munitions centre. The vast number of workmen near the factories at meal times show the force of the workers; but the flurry of activity at night is not as generally observed by the public. It will surprise people some day to learn how greatly Coventry contributed to the output of munitions for * both Great Britain and her Allies.” A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Masters by Research in Historical Geography October 2008 Department of Geography, Faculty of Business, Environment and Society Coventry University * The editor writing in the Coventry Graphic 17th September 1915 p3 emphasis added. -

Bmw 2002 Alpina

COWLEY CARS VOLKSWAGEN CARACAL BIMOTA Morris Bullnose South African built sportscar Kawasaki KB1/3 R46.95 incl VAT • August/September 2013 BMW 2002 THE BEST FOR ALPINA ROAD & TRACK COUNTACH 1959 CHEVY Celebrating 50 years of Lamborghini with Spreading the wings with range, fi ns, excess the ultimate pin-up and extravagance ANDY TERLOUW | JIMMY DE VILLIERS | VAN DER LINDE DYNASTY FOR BOOKINGS 0861 11 9000 proteahotels.com IF PETROL RUNS IN YOUR VEINS, THIS IS A SIREN CALL TO THE OPEN ROAD... TO BOOK THIS & MANY MORE GREAT MOTORING SPECIALS VISIT proteahotels.com/motoring PRETORIA CARS IN THE PARK CAPE CLASSIC CAR SHOW ZWARTKOPS RACEWAY, PRETORIA JAN BURGER SPORTS COMPLEX, BELLVILLE 4 AUGUST 2013 3 NOVEMBER 2013 PROTEA HOTEL CENTURION PROTEA HOTEL TYGER VALLEY Protea Hotel Centurion is located midway between Johannesburg and Protea Hotel Tyger Valley is great value for money, ideally located 6 Pretoria and is just a short drive away from the Zwartkops race track. minutes’ drive from the show grounds in Bellville. * * R350 per person sharing, per night R350 per person sharing, per night Includes secure parking, welcome drink on arrival and Includes secure parking for cars and trailers and 500MB complimentary Wi-Fi per day. 500MB complimentary Wi-Fi per day. *Terms and conditions apply. PHDS 27689/13 CONTENTS August/September 2013 ONE, NOT FIFTY SHADES OF RED THE DEVELOPMENT GAME 04 A tour of Maranello and Modena 66 Ford’s Fiesta compared with classics HIGH OCTANE FAST ON TWO & FOUR 08 Coucher, Wilbur Smith and a 70 Racer, cyclist and business -

NEWSLETTER Historians ISSUE NO

Zlie Society if Automotive NEWSLETTER Historians ISSUE NO. 57 MARCH 1978 SAH NEWSLETTER TO HAVE NEW EDITOR one has any ideas, contact Fred Soule at 9 Greenport Parkway, Hudson, NY 12534, or bring them to the !ULY lST next meeting. Dues for the new region have been set at $5.00 per year, with national membership a prerequisite. Starting on July 1, 1978, Walter Godsen of Floral Dues may be mailed to Margaret M. Vitale, Box 63, Park, NY will assume the post of Editor of the SAH Lake Grove, NY 11755. There will be no membership NE'.,'S t.t:!"i' SR . Val ter will replace the current Editor, cards issued. News and announcements will appear 1n John PPckham, wh? has been .involved with .producing - the SAH NE\vSLETTER. or editing of t!1.e NE'•ISLEI'TER since March 1975. The next meeting of the Region will be Sunday, Aesisting Godsen in production and mailing of May 14, 1978 at Henry Austin Clark's residence, the NL will be Margaret Vitale, of Lake Grove, NY. Meadow Spring, Glen Cove, Long Island, NY. Notices Margaret will be taking over the work that has been will be sent to members within the Region. Others done previously by Fred Roe. Actually, r.he will be interested, please write to Margaret Vitale at the starting her part of the job with this issue. above address. National business was discussed, as well as regional matters. Pres. Applegate announced that IS THE NORTHEASTERN REGION THE John M. Peckham would be the Chairman of the Nominating Committee this year. -

Vintage Motorcycle Club Newsletter Kickstart 2016 11

A monthly publication of The Vintage Motorcycle Club Johannesburg, South Africa. Volume 31. No 11. November 2016 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE: Motorcycling is a pastime full of variation. Since the inception of a motorised two wheeler, anyone wanting to be part of a world in which you aren’t cossetted in a cocoon of steel and glass opted for the open road on a motorcycle. This gave rise to various interesting characters that frequent the annals of motorcycle history. From the Tourer, to the Sportster, Stunt rider and more recently the Adventure rider (read Martin Davis) our brothers and sisters take to the roads, tracks and countryside on all forms of two or three wheeled moped. Our own society and movement has a very specific bond with motorcycling and the older, the better. However as we age, we need to inject newer blood into our movement to keep it going. This predicament isn’t unique to VMC as all hobbies and pastimes are struggling to keep their “induction ports” above water these days. It is essential to bring younger enthusiasts to our gatherings, both to introduce new blood and get the generation who inherited their parent’s motorcycles to bring them into the fold. Your ideas on how we can do this will be most welcome; also getting together from a social perspective and riding more as a club can make our movement more visible. In this regard, the committee will plan regular club rides, over and above the main Regularity and Commemorative events, while encouraging all members to get out there and “exercise the steeds”. -

Warwickshire Industrial Archaeology Society Please

WARWICKSHIRE IndustrialW ArchaeologyI SociASety NUMBER 21 December 2005 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER THIS ISSUE also became noticeable. Reminders for outstanding Strictly these remains represent payments will be sent out after ¢ Meeting Reports landscape archaeology, but the Christmas. inference for field industrial archaeology is clear. Snowfall, Newsletter mailing ¢ Cob low sunlight and an area of Those members who are unable known past industrial activity may to attend meetings regularly may ¢ Website Update reveal more to careful inspection have noticed the absence of the than might be apparent under usual Newsletter mailings during ¢ 2006 Programme more usual weather. the latter part of this year. This is Mark W. Abbott due to a computer upgrade, which has made the address EDITORIAL SOCIETY NEWS databases used for this mailing he value of snow for Programme. inaccessible, along with the industrial archaeology in The programme through to database that holds subscription the field was not March 2006, is as follows: records. This should be a T January 12th temporary problem, albeit one of something I had considered until the snowfall around Southam at Mr. Roger Cragg: Thomas rather longer duration than was the end of November. Brassey. originally envisaged! In the Out and about in the course of February 9th meantime, a stock of past my job, I had to travel to Burton Mr. Tim Booth: Emscote Mill. Newsletters is always available at Dasset and then Avon Dasset. March 9th meetings, so please ask if you This was an interesting exercise in Mr. Jeromy Hassell: White and think you have missed a copy. All itself as the minor roads had not Poppe. -

Basic Motoring

Basic motoring The Evolution of the Modern Ultralight Economy car. Honda Zest Preface I began writing this book because no one else has covered the subject comprehensively, there are a lot of books and web pages on individual models that go into minute often extremely boring details but there is nothing to link all of this class of car together that show how the modern ultralight economy car we use today has evolved. First I must explain what I mean by the rather long winded term ultralight economy car. The type of car or if you prefer automobile, that I refer to below can be classified today by many labels, minicar, economy car, city car, mini compact if you are from USA or an A-segment mini car if you are a European official. None of these describe exactly the type of car I have included in this text. Yes, they were economy cars but very small economy cars with an engine capacity range with some latitude; from 360 cc to 1000 cc. Some could be classed as mini or city cars but not all are and some could be classed as microcars, but they were and are all a relatively low cost form of transport for a great many millions of people around the world in the past and increasingly so today. Page 1 Basic Motoring Austin Voiturette 1909 Introduction. Before the advent of the autobahn, autostrada and motorway, most European urban based car owners and most of those living in the country were content to drive around at a moderate speed, which was all that road conditions would allow.