The Old Believers of Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO. 9 DECEMBER 2017 COVER: ICON OF THE NATIVITY EDITORIAL Handwritten icon by Khourieh Randa Al Khoury Azar Using old traditional technique contents [email protected] 3 EDITORIAL CELEBRATING CHRISTMAS by Bishop JOHN 5 PLEADING FOR THE LIVES OF THE DEFINES US PEOPLE OF THE MIDDLE EAST: THE U.S. VISIT OF HIS BEATITUDE PATRIARCH JOHN X OF ANTIOCH EVERYONE SEEMS TO BE TALKING ABOUT IDENTITY THESE DAYS. IT’S NOT JUST AND ALL THE EAST by Sub-deacon Peter Samore ADOLESCENTS WHO ARE ASKING THE FUNDAMENTAL QUESTION, “WHO AM I?” RATHER, and Sonia Chala Tower THE QUESTION OF WHAT IT IS TO BE HUMAN IS RAISED IMPLICITLY BY MANY. WHILE 8 PASTORAL LETTER OF HIS EMINENCE METROPOLITAN JOSEPH PHILOSOPHERS AND PSYCHOLOGISTS HAVE ADDRESSED THIS QUESTION OF HUMAN 9 I WOULD FLY AWAY AND BE AT REST: IDENTITY OVER THE YEARS, GOD ANSWERED IT WHEN THE WORD BECAME FLESH AND THE LAST PUBLIC APPEARANCE AND FUNERAL OF DWELT AMONG US. HE TOOK ON OUR FLESH SO THAT WE MAY PARTICIPATE IN HIS HIS GRACE BISHOP ANTOUN DIVINITY. CHRIST REVEALED TO US WHO GOD IS AND WHO WE ARE TO BE. WE ARE CALLED by Sub-deacon Peter Samore 10 THE GHOST OF PAST CHRISTIANS BECAUSE HE HAS MADE US AS LITTLE CHRISTS BY ACCEPTING US IN BAPTISM CHRISTMAS PRESENTS AND SHARING HIMSELF IN US. JUST AS CHRIST REVEALS THE FATHER, SO WE ARE TO by Fr. Joseph Huneycutt 13 RUMINATION: ARE WE CREATING REVEAL HIM. JUST AS CHRIST IS THE INCARNATION OF GOD, JOINED TO GOD WE SHOW HIM OLD TESTAMENT CHRISTIANS? TO THE WORLD. -

Overview August 2020

Middle East Overview – August 2020 Winds of Change? President Macron landing in Beirut’s airport and greeting President Michel Aoun, August 6, 2020, photo credit: egyptindependent.com MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW | August 2020 Contents 1. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC SITUATION ......................................................................................................................... 3 Egypt ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Jordan .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Iraq ............................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Lebanon ....................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Palestine ...................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Syria ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

CHURCH and PEOPLE " Holyrussia," the Empire Is Called, and the Troops of The

CHAPTER V CHURCH AND PEOPLE " HOLYRussia," the Empire is called, and the troops of the Tsar are his " Christ-loving army." The slow train stops at a wayside station, and..among the grey cot- The Church. tages on the hillside rises a white church hardly supporting the weight of a heavy blue cupola. The train approaches a great city, and from behind factory chimneys cupolas loom up, and when the factory chimneys are passed it is the domes and belfries of the churches that dominate the city. " Set yourselves in the shadow of the sign of the Cross, O Russian folk of true believers," is the appeal that the Crown makes to the people at critical moments in its history. With these words began the Manifesto of Alexander I1 announcing the emancipation of the serfs. And these same words were used bfthose mutineers on the battleship Potenzkin who appeared before Odessa in 1905. The svrnbols of the Orthodox Church are set around Russian life like banners, like ancient watch- towers. The Church is an element in the national conscious- ness. It enters into the details of life, moulds custom, main- tains a traditional atmosphere to the influence of which a Russian, from the very fact that he is a Russian, involuntarily submits. A Russian may, and most Russian intelligents do, deny the Church in theory, but in taking his share in the collective life of the nation he, at many points, recognises the Ch'urch as a fact. More than that. In those borcler- lands of emotion that until life's end evade the control of toilsomely acquired personal conviction, the Church retains a foothold, yielding only slowly and in the course of generations to modern influences. -

Russian Copper Icons Crosses Kunz Collection: Castings Faith

Russian Copper Icons 1 Crosses r ^ .1 _ Kunz Collection: Castings Faith Richard Eighme Ahlborn and Vera Beaver-Bricken Espinola Editors SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Stnithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsoniar) Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the worid of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the worid. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where tfie manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Bull.MAY9-Thomas Sunday

n those days, many signs and wonders were done among the people By the hands of the apostles; Saint George Antiochian Orthodox Christian Church and they were all together in Solomon’s portico. None of the rest dared join them, but the people I held them in high honor. And more than ever believers were added to the Lord, multitudes both 1250 Oakdale Avenue, West Saint Paul, Minnesota 55118 of men and women, so that they even carried out the sick into the streets, and laid them on beds Parish Website: http://www.saintgeorge-church.org and pallets, that as Peter came by at least his shadow might fall on some of them. The people also Church Phone: 651-457-0854 gathered from the towns around Jerusalem, bringing the sick and those afflicted with unclean spir- its, and they were all healed. The Most Reverend Metropolitan JOSEPH, Archbishop of New York, But the chief priest rose up and all who were with him, that is, the party of the Sadducees, and Metropolitan of all North America filled with jealousy they arrested the apostles and put them in the common prison. But at night an Right Reverend Bishop ANTHONY, Auxiliary angel of the Lord opened the prison doors and brought them out and said: “Go and stand in the Bishop of the Diocese of Toledo and the Midwest temple and speak to the people all the words of this Life.” Right Reverend Archimandrite John Mangels, Pastor GOSPEL: Reverend Father John Chagnon, attached Very Reverend Archpriest Paul Hodge, attached The Reading from the Holy Gospel according to St. -

Putin Claims to Be the Defender of Christians, Jews and Muslims in Syria

Putin claims to be the defender of Christians, Jews and Muslims in Syria. What about “the West”? By Willy Fautré at the 3rd Archon Conference on religious freedom in the Middle East (Washington) HRWF (07.12.2017) – Putin has recently and openly upgraded his support to the return of Christians, Jews and Muslims in Syria. He has also promised to participate in the reconstruction of the country. He has mentioned the work of a special task force including members of the Russian Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, who are compiling a catalogue of churches destroyed in Syria with a view to their restoration. The question is “Will the US, the EU and the heads of its member states raise their voices to pledge they will participate in the reconstruction of the safe parts of the country, rebuild and restore churches, community buildings and schools so that Syrian refugees will want to back home or … will they leave Putin reaping the gratitude of the Syrian people ?” The influence and the credibility of the EU in the region today and tomorrow is at stake in this matter. Patriarch of Antioch thanks Lavrov for Russia's efforts to settle Syrian crisis Interfax-Religion/ Russia (05.12.2017) - http://bit.ly/2ACh8nh - Patriarch John X of Antioch and All the East has praised Russia's efforts in Syria, which helped put an end to terrorism and extremism in that country. "Over the past two years, with the Russian army's help, terrorism has been destroyed, putting an end to extremism and killings," he said at a meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov on Tuesday, recalling that the Syrian army has also managed to retake control over all of the territory earlier seized by ISIL (banned in Russia). -

SEPTEMBER 2015 WORD CONVENTION.Indd

Volume 59 No. 7 September 2015 Patriarch JOHN X AND THE 52ND ANTIOCHIAN ARCHDIOCESAN CONVENTION VOLUME 59 NO. 7 SEPTEMBER 2015 contents COVER: PATRIARCH JOHN X AT THE 52ND ARCHDIOCESAN CONVENTION 3 EDITORIAL by Bishop JOHN 5 HIS BEATITUDE JOHN X ADDRESSES THE ARCHDIOCESAN CONVENTION 10 HIS EMINENCE METROPOLITAN JOSEPH ADDRESSES THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE 52ND ARCHDIOCESAN CONVENTION 16 ARCHDIOCESAN CONVENTION HOMILY by Archpriest Paul O’Callaghan 20 PATRIARCH JOHN X STRESSES UNITY, PEACE, AT ACADEMIC CONVOCATION The Most Reverend Metropolitan JOSEPH 22 DAILY DEVOTIONS The Right Reverend Bishop ANTOUN 23 PATRIARCH JOHN X THANKS The Right Reverend ST. VLADIMIR SEMINARY FOR Bishop BASIL HONORARY DOCTORATE The Right Reverend 24 A SYNAXIS OF THE ANTIOCHIAN WORLD: Bishop THOMAS A REPORT ON THE 52ND CONVENTION OF The Right Reverend THE ANTIOCHIAN ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN Bishop ALEXANDER ARCHDIOCESE OF NORTH AMERICA by Sub-deacon Peter Samore The Right Reverend Bishop JOHN 30 ST. RAPHAEL, THE SERVANT The Right Reverend by Economos Antony Gabriel Bishop ANTHONY The Right Reverend 32 RESOLUTIONS Bishop NICHOLAS Founded in Arabic as 35 ARCHDIOCESAN OFFICE Al Kalimat in 1905 by Saint Raphael (Hawaweeny) Founded in English as The WORD in 1957 July 25, 2015 by Metropolitan ANTONY (Bashir) Editor in Chief The Rt. Rev. Bishop JOHN, D.Min. Assistant Editor Christopher Humphrey, Ph.D. Patriarch Editorial Board The Very Rev. Joseph J. Allen, Th.D. Anthony Bashir, Ph.D. The Very Rev. Antony Gabriel, Th.M. Ronald Nicola Najib E. Saliba, Ph.D. JOHN X Letters to the editor are welcome and should include the author’s full name and parish. -

S T. P a N Te Le Im O N O Rth O D O X C H U Rc H

St. Panteleimon Orthodox Church OCA - Diocese of the Midwest Fr. Andrew Bartek, Rector V. Rev. Anthony Spengler,Attached Protodeacon Robert Northrup Reader James Tilghman Parish Council President: Nicholas Cavaligos Steve Grabavoy orSteve Hruban toMark contribute. the before This collection will take place during the Litany Sunday, February7, 2016 Tone 3 Basement Rectory /Church School L. / 9:30am:D. Panachida@ Social 40 / Day Hours 9:10am: Sunday, February14 Saturday, February 13 FebruaryWednesday, 10 7:30pm: Monthly HealingService 6:00pm: Chamber of CommerceMeeting Tuesday, February9 9:30am:D.L./ 40 9:10am:Hours Sunday, February7 (Children’s Sunday) Gospel 40 Days Eternal Memory February 27: Terrorist attack @ Palestine Univ. @February 27:Terroristattack Palestine February 21:Matthew / Lyons Catherine February 14:HelenPender McGurkFebruary 7:Bernice 11:00 am-2:00 pm& 4:00pm-8:00 pm 6:00 pm:6:00 Vespers Great 11:00 am will WinterCamp Begins- WI (we 36h Sunday /St. after Pentecost Vladimir, /NewHieormartyrs Parthenius & Met. Kiev Liturgical & Event Schedule 7549 West61st Summit, Illinois Place, 60501 Rectory 708-552-5276 570-212-8747/ Cell Hawaii &Hawaii Joshua Zdinak 16 Marineskilledinhelicopter in crash 2016 -SPECIALCOLLECTIONS FISH FRY @ FUNDRAISER StBlase : St. 15:21-28 Matthew : Our Father. Our Father. February: StVladmir’s Seminary leave @ 9:00am) leave Mr. &Mrs.Andre Davik fortheHealthofFamily th DayPanachida / Social Or you canspeak to website: http://www.saintpanteleimon.org/ February Bulletin SponsorFebruary Bulletin Abp. Peter -

Russian Dissenters

>^ ifStil:.^ HARVARD THEOLOGICAL STUDIES ,,1 HARVARD THEOLOGICAL STUDIES EDITED FOR THE FACULTY OF DIVINITY IN HARVARD UNIVERSITY BY GEORGE F. MOORE, JAMES H. ROPES KIRSOPP LAKE (IHMiUlfHtiniiiilll CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON: HUMPHREY MILFORD OxjORD University Press I92I HARVARD THEOLOGICAL STUDIES X RUSSIAN DISSENTERS FREDERICK crcONYBEARE HONORARY FELLOW UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, OXFORD .-4 CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON: HUilPHREY MILFORD OxYou> UmvEKsmr Pkkss I921 COPYMGHT, I92I HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS 6677B4 13 1' S 7 PRINTED AT THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS CAMBRIDQE, MASS., UNITED STATES OF AMERICA '^ inof se: 2 PREFACE This work was begun in 1914 and completed nearly as it stands early in 1917, about the time when the Russian Revolution began. It is too early yet to trace the fortunes of the Russian sects during this latest period, for the contradictory news of the struggle is not to be trusted; and few, if any, know what is really happening or has happened in unhappy Russia. Since, however, the future is largely moulded by the past, I trust that my work may be of some use to those who sincerely desire to understand and trace out the springs of the Revolu- tion. It is not a work of original research. I have only read a number of Russian authorities and freely exploited them. I have especially used the Historj' of the Russian Ra^kol by Ivanovski (two volumes, Kazan, 1895 and 1897). He was professor of the subject in the Kazan Seminary between 1880 and 1895. He tries to be fair, and in the main succeeds in being so. Subbotin, indeed, in a letter to Pobedonostzev, Procurator of the Holy SjTiod, who had consisted him about the best manuals on the subject, wrote shghtingly of the work; but I think unfairiy, for the only concrete faults he finds with it are, first, that the author allowed himself to use the phrase; 'the historical Christ,' which had to his ears a rationalist ring; and secondly, that he devoted too Uttle space to the Moscow Synods of 1654 to 1667. -

Building Confidence, Building Bonds

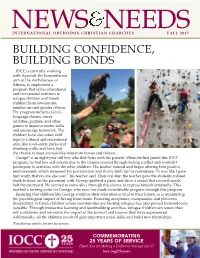

NINTERNAETIONALWS ORTHODOX CHRISTIA NEEDSN CHARITIES FALL 2017 BUI LDING CONFIDENCE, BUI LDING BONDS IOCC is currently working with Apostoli, the humanitarian arm of the Archdiocese of Athens, to implement a program that offers educational and recreational activities to refugee children and Greek children from low-income families around greater Athens. The program includes Greek- language classes, music activities, puzzles, and other games to improve motor skills and encourage teamwork. The children have also taken field trips to cultural and recreational C C C C O O I sites, like road-safety parks and I climbing walls, and have had the chance to meet animals like miniature horses and falcons. George* is an eight-year-old boy who fled Syria with his parents. When he first joined this IOCC program, he had low self-esteem due to the trauma created through feeling conflict and wouldn’t participate in activities with the other children. His teacher noticed and began offering him positive reinforcement, which increased his participation and slowly built up his confidence. “It was like I gave him worth that no one else saw,” his teacher said. Then one day, the teacher gave the students colored chalk to draw on the pavement with. George grabbed a piece and drew a mural that covered nearly half the courtyard. He seemed to come alive through this chance to express himself artistically. This marked a turning point for George, who now has made considerable progress through this program. Ensuring that children like George continue their education is vital to their future, as is minimizing the psychological impact of fleeing from home. -

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk meets with His Beatitude Patriarch John X of Antioch On 9 November 2013, Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department for External Church Relations (DECR), currently on a visit to Lebanon with the blessing of His Holiness Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia, visited the Monastery of the Dormition of the Theotokos in Balamand, where he was received by His Beatitude John X, Patriarch of the Great Antioch and All the East. They were joined in the meeting by Archbishop Nifon of Philippopolis, representative of the Patriarch of Antioch in Moscow; Bishop Gattas of Kars, hegumen of the monastery; and archpriest Igor Yakimchuk, DECR secretary for inter-Orthodox relations. Metropolitan Hilarion conveyed fraternal greetings from His Holiness Patriarch Kirill to the Primate of the Orthodox Church of Antioch. His Beatitude John X remarked that the Patriarchate of Antioch and Moscow are linked by centuries-old bonds of love and brotherhood and expressed cordial gratitude to the Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian authorities for their strong stand on the defence of Christian in the Middle East and for the assistance they have rendered. The DECR chairman expressed deep concern about tragic events in Syria and underscored that the Russian Orthodox Church will continue to do anything in her power to alleviate sufferings of the victims of military conflict in Syria. Metropolitan Hilarion also noted a positive example of Lebanon where much is being done for maintaining interreligious and inter-ethnic accord, while representatives of different religious and national communities work actively together for the prosperity of the country. -

The Epistle St

The Epistle St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church January 22909 Center Ridge Road, Rocky River, Ohio 2015 Pastoral Thoughts The Balourdas Hellenic Cultural School PTO by Fr. Jim Doukas cordially invites you to the annual Dear Parishioners, Three Hierarchs & Greek Letters Happy New Year! The first of the year is an Day Program interesting time of the year – centered on th reflection and resolution. We use this time Sunday, January 25 to reflect on the year that just ended and from that we naturally evolve into what we can learn from that reflection Memorial for deceased educators of our parish and resolve to make the New Year better. In every aspect of and an actual sermon of St. John Chrysostom, our lives, we resolve to be better or to do more than what we following the Divine Liturgy did. At work, we strive to be more productive; at home, we take steps to spend more quantity (and quality) time with family and friends; and for our own selves, we resolve to eat Greek School Open House – all welcome to healthier, lose weight, and exercise. I am prayerful that visit the classrooms and meet our teachers another aspect of reflection and resolution is in our spiritual lives. Brunch in the Cultural Hall As we look back on 2014, we should reflect on the effort we made in the areas of worship/prayer (both private and with special video presentations, and corporate), reading the Bible, and study of the teachings of the Keynote Speaker Dr. Pete N. Poolos , Fathers. Fasting, almsgiving and other Christian virtues amateur Ancient Greek historian & should also make the list in our spiritual reflection of 2014.