HOGUE-DISSERTATION-2019.Pdf (1.297Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booklet Shakespeare 3

SONNET 1 From fairest creatures we desire increase, That thereby beauty’s rose might never die, But as the riper should by time decease, His tender heir might bear his memory: But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes, Feed’st thy light’st flame with self-substantial fuel, Making a famine where abundance lies, Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel. Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament And only herald to the gaudy spring, Within thine own bud buriest thy content And, tender churl, makest waste in niggarding. Pity the world, or else this glutton be, To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee. SONNET 18 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm’d; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d; But thy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest; Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou growest: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. SONNET 29 When, in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes, I all alone beweep my outcast state, And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries, And look upon myself, and curse my fate, Wishing me like to one more rich in hope, Featur'd like him, like him with friends possess'd, Desiring this man's art and that man's scope, With what I most enjoy contented least; Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, Haply I think on thee, and then my state, Like to the lark at break of day arising From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate; For thy sweet love remember'd such wealth brings That then I scorn to change my state with kings. -

Aitken Alexander Associates

Aitken Alexander Associates Frankfurt Book Fair 2019 For further information on all clients and titles in this catalogue, please contact: LISA BAKER France, Germany, Holland and Italy Email: [email protected] ANNA WATKINS Brazil, China, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Japan, Korea, Norway, Portugal, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Taiwan Email: [email protected] MONICA MACSWAN Arabic, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Indian Languages, Indonesia, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Mongolia, Thailand, Turkey, Serbia, Slovenia, Vietnam Email: [email protected] Literary Agents Centre Tables: Anna – 21P, Monica – 21Q, Lisa – 22Q For Film and Television Rights please contact: LESLEY THORNE Email: [email protected] Aitken Alexander Associates Ltd. 291 Gray’s Inn Road London WC1X 8QJ Telephone (020) 7373 8672 www.aitkenalexander.co.uk @AitkenAlexander @aitkenalexander Contents Page Fiction: Saltwater by Jessica Andrews p.1 The Body Lies by Jo Baker p.2 Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo p.3 This Brutal House by Niven Govinden p.4 The Porpoise by Mark Haddon p.5 The Harpy by Megan Hunter p.6 Sisters by Daisy Johnson p.7 Nightingale by Marina Kemp p.8 Isabelle in the Afternoon by Douglas Kennedy p.9 When We Were Rich by Tim Lott p.10 The Anthill by Julianne Pachico p.11 The Inheritance of Solomon Farthing by Mary Paulson-Ellis p.12 Mister Wolf by Chris Petit p.13 All the Water in the World by Karen Raney p.14 English Monsters by James Scudamore p.15 The -

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the Plays of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the plays of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas. A submission for the degree of doctor of philosophy by Stephen David Collins. The Department of History of The University of York. June, 2016. ABSTRACT. Families transact their relationships in a number of ways. Alongside and in tension with the emotional and practical dealings of family life are factors of an essentially moral nature such as loyalty, gratitude, obedience, and altruism. Morality depends on ideas about how one should behave, so that, for example, deciding whether or not to save a brother's life by going to bed with his judge involves an ethical accountancy drawing on ideas of right and wrong. It is such ideas that are the focus of this study. It seeks to recover some of ethical assumptions which were in circulation in early modern England and which inform the plays of the period. A number of plays which dramatise family relationships are analysed from the imagined perspectives of original audiences whose intellectual and moral worlds are explored through specific dramatic situations. Plays are discussed as far as possible in terms of their language and plots, rather than of character, and the study is eclectic in its use of sources, though drawing largely on the extensive didactic and polemical writing on the family surviving from the period. Three aspects of family relationships are discussed: first, the shifting one between parents and children, second, that between siblings, and, third, one version of marriage, that of the remarriage of the bereaved. -

Priscilla: the Hidden Life of an Englishwoman in Wartime France Free

FREE PRISCILLA: THE HIDDEN LIFE OF AN ENGLISHWOMAN IN WARTIME FRANCE PDF Nicholas Shakespeare | 464 pages | 03 Jul 2014 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099555667 | English | London, United Kingdom Priscilla: The Hidden Life of an Englishwoman in Wartime France - Wikipedia Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will Priscilla: The Hidden Life of an Englishwoman in Wartime France you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. NOOK Book. Home 1 Books 2. Read an excerpt of this book! Add to Wishlist. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Members save with free shipping everyday! See details. The glamorous, mysterious figure he remembered from his childhood was very different from the morally ambiguous young woman who emerged from the trove of love letters, journals and photographs, surrounded by suitors and living the precarious existence of a British citizen in a country controlled by the enemy during World War II. As a young boy, Shakespeare had always believed that his aunt was a member of the Resistance and had been tortured by the Priscilla: The Hidden Life of an Englishwoman in Wartime France. The truth turned out to be far more complicated. Series Pages: Sales rank:Product dimensions: 5. About the Author Nicholas Shakespeare's books have been translated into twenty languages. His nonfiction includes the critically acclaimed authorized biography of Bruce Chatwin. Shakespeare is married with two sons and lives in Oxford. -

"The Problem of Predicting What Will Last"

Allan Massie, "The Problem of Predicting What Will Last" Booksonline, with Amazon.co.uk (An Electronic Telegraph Publication) 4 January 2000 As our Book of the Century series concludes, Allan Massie compares the list with one published by The Daily Telegraph 100 years ago EACH WEEK for the past two years The Daily Telegraph’s literary editor has asked a contributor to name and describe his or her "Book of the Century", and today the series concludes with Arthur C. Clarke’s choice. The full selection invites comparison with a list drawn up by The Telegraph a century ago; we print both here. The comparison cannot, however, be exact. All the books chosen in 1899 were fiction - the paper offered its readers the "100 Best Novels in the World", selected by the editor "with the assistance of Sir Edwin Arnold, K. C. I. E, H. D. Traill, D. C. L, and W. L. Courtney, LL. D.". The modern list includes poetry, plays, history, diaries, philosophy, economics, memoirs, biography and travel writing. It is certainly eclectic, ranging from Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, selected by David Sylvester, to The Wind in the Willows, chosen by John Bayley, and Down with Skool, Wendy Cope’s Book of the Century. The 1899 list, on offer at the time in a cloth-bound edition at nine guineas the lot (easy terms available), is homogeneous, as the modern one is not, not only because it consists entirely of works of fiction but also because the selection was made by a small group. And since they were picking the 100 Best Novels, they were able to include books that nobody might name as a single "Book of the Century" but which many might put in their top 20 or so. -

Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 094 892 PS 007 449 AUTHOR Snyder, Agnes TITLE Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 421p. AVAILABLE FROM Association for Childhood Education International, 3615 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 ($9.50, paper) EDRS PRICE NF -$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Biographical Inventories; *Early Childhood Education; *Educational Change; Educational Development; *Educational History; *Educational Philosophy; *Females; Leadership; Preschool Curriculum; Women Teachers IDENTIFIERS Association for Childhood Education International; *Froebel (Friendrich) ABSTRACT The lives and contributions of nine women educators, all early founders or leaders of the International Kindergarten Union (IKU) or the National Council of Primary Education (NCPE), are profiled in this book. Their biographical sketches are presented in two sections. The Froebelian influences are discussed in Part 1 which includes the chapters on Margarethe Schurz, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Susan E. Blow, Kate Douglas Wiggins and Elizabeth Harrison. Alice Temple, Patty Smith Hill, Ella Victoria Dobbs, and Lucy Gage are- found in the second part which emphasizes "Changes and Challenges." A concise background of education history describing the movements and influences preceding and involving these leaders is presented in a single chapter before each section. A final chapter summarizes the main contribution of each of the women and also elaborates more fully on such topics as IKU cooperation with other organizations, international aspects of IKU, the writings of its leaders, the standardization of curriculuis through testing, training teachers for a progressive program, and the merger of IKU and NCPE into the Association for Childhood Education.(SDH) r\J CS` 4-CO CI. -

Transgender Woman 'Raped 2,000 Times' in All-Male Prison

A transgender woman was 'raped 2,000 times' in all-male prison Transgender woman 'raped 2,000 times' in all-male prison 'It was hell on earth, it was as if I died and this was my punishment' Will Worley@willrworley Saturday 17 August 2019 09:16 A transgender woman has spoken of the "hell on earth" she suffered after being raped and abused more than 2,000 times in an all-male prison. The woman, known only by her pseudonym, Mary, was imprisoned for four years after stealing a car. She said the abuse began as soon as she entered Brisbane’s notorious Boggo Road Gaol and that her experience was so horrific that she would “rather die than go to prison ever again”. “You are basically set upon with conversations about being protected in return for sex,” Mary told news.com.au. “They are either trying to manipulate you or threaten you into some sort of sexual contact and then, once you perform the requested threat of sex, you are then an easy target as others want their share of sex with you, which is more like rape than consensual sex. “It makes you feel sick but you have no way of defending yourself.” Mary was transferred a number of times, but said Boggo Road was the most violent - and where she suffered the most abuse. After a failed escape, Mary was designated as ‘high-risk’, meaning she had to serve her sentence as a maximum security prisoner alongside the most violent inmates. “I was flogged and bashed to the point where I knew I had to do it in order to survive, but survival was basically for other prisoners’ pleasure,” she said. -

Moral Philosophers and the Novel a Study of Winch, Nussbaum and Rorty

Moral Philosophers and the Novel A Study of Winch, Nussbaum and Rorty Peter Johnson Moral Philosophers and the Novel Also by Peter Johnson R. G. COLLINGWOOD: An Introduction THE CORRESPONDENCE OF R. G. COLLINGWOOD: An Illustrated Guide FRAMES OF DECEIT THE PHILOSOPHY OF MANNERS: A Study of the ‘Little Virtues’ POLITICS, INNOCENCE AND THE LIMITS OF GOODNESS Moral Philosophers and the Novel A Study of Winch, Nussbaum and Rorty Peter Johnson Department of Philosophy University of Southampton, UK © Peter Johnson 2004 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2004 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. -

Poetry As Correspondence in Early Modern England

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Unfolding Verse: Poetry As Correspondence In Early Modern England Dianne Marie Mitchell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Mitchell, Dianne Marie, "Unfolding Verse: Poetry As Correspondence In Early Modern England" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2477. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2477 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2477 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unfolding Verse: Poetry As Correspondence In Early Modern England Abstract This project recovers a forgotten history of Renaissance poetry as mail. At a time when trends in English print publication and manuscript dissemination were making lyric verse more accessible to a reading public than ever before, writers and correspondents created poetic objects designed to reach individual postal recipients. Drawing on extensive archival research, “Unfolding Verse” examines versions of popular poems by John Donne, Ben Jonson, Mary Wroth, and others which look little like “literature.” Rather, these verses bear salutations, addresses, folds, wax seals, and other signs of transmission through the informal postal networks of early modern England. Neither verse letters nor “epistles,” the textual artifacts I call “letter-poems” proclaim their participation in a widespread social -

Post-Deconstructive Subjectivity and History: Phenomenology, Critical Theory, and Postcolonial Thought

Post-deconstructive Subjectivity and History: Phenomenology, Critical Theory, and Postcolonial Thought By Aniruddha Chowdhury A Dissertation Submitted To The Faculty of Graduate Studies In Partial Satisfaction Of The Requirements For The Degree Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program In Social and Political Thought York University, Toronto, Ontario [September 2011] Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88661-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88661-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Exploring Shakespeare's Sonnets with SPARSAR

Linguistics and Literature Studies 4(1): 61-95, 2016 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2016.040110 Exploring Shakespeare’s Sonnets with SPARSAR Rodolfo Delmonte Department of Language Studies & Department of Computer Science, Ca’ Foscari University, Italy Copyright © 2016 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Shakespeare’s Sonnets have been studied by rhetorical devices. Most if not all of these facets of a poem literary critics for centuries after their publication. However, are derived from the analysis of SPARSAR, the system for only recently studies made on the basis of computational poetry analysis which has been presented to a number of analyses and quantitative evaluations have started to appear international conferences [1,2,3] - and to Demo sessions in and they are not many. In our exploration of the Sonnets we its TTS “expressive reading” version [4,5,6]1. have used the output of SPARSAR which allows a Most of a poem's content can be captured considering full-fledged linguistic analysis which is structured at three three basic levels or views on the poem itself: one that covers macro levels, a Phonetic Relational Level where phonetic what can be called the overall sound pattern of the poem - and phonological features are highlighted; a Poetic and this is related to the phonetics and the phonology of the Relational Level that accounts for a poetic devices, i.e. words contained in the poem - Phonetic Relational View. -

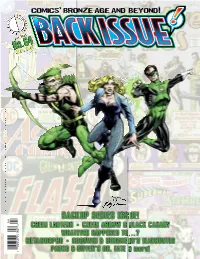

Backup Series Issue! 0 8 Green Lantern • Green Arrow & Black Canary 2 6 7 7

0 4 No.64 May 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 METAMORPHO • GOODWIN & SIMONSON’S MANHUNTER GREEN LANTERN • GREEN ARROW & BLACK CANARY COMiCs PASKO & GIFFEN’S DR. FATE & more! , WHATEVER HAPPENED TO…? BACKUP SERIES ISSUE! bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 64 May 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics of Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Mike Grell and Josef Rubinstein COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: The Emerald Backups . .3 Green Lantern’s demotion to a Flash backup and gradual return to his own title SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Robert Greenberger FLASHBACK: The Ballad of Ollie and Dinah . .10 Marc Andreyko Karl Heitmueller Green Arrow and Black Canary’s Bronze Age romance and adventures Roger Ash Heritage Comics Jason Bard Auctions INTERVIEW: John Calnan discusses Metamorpho in Action Comics . .22 Mike W. Barr James Kingman The Fab Freak of 1001-and-1 Changes returns! With loads of Calnan art Cary Bates Paul Levitz BEYOND CAPES: A Rose by Any Other Name … Would be Thorn . .28 Alex Boney Alan Light In the back pages of Lois Lane—of all places!—sprang the inventive Rose and the Thorn Kelly Borkert Elliot S! Maggin Rich Buckler Donna Olmstead FLASHBACK: Seven Soldiers of Victory: Lost in Time Again . .33 Cary Burkett Dennis O’Neil This Bronze Age backup serial was written during the Golden Age Mike Burkey John Ostrander John Calnan Mike Royer BEYOND CAPES: The Master Crime-File of Jason Bard .