1. What Is a Trade Mark?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cigars Were Consumed Last Year (1997) in the United States

Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9 Preface The recent increase in cigar consumption began in 1993 and was dismissed by many in public health as a passing fad that would quickly dissipate. Recently released data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) suggests that the upward trend in cigar use might not be as temporary as some had predicted. The USDA now projects a total of slightly more than 5 billion cigars were consumed last year (1997) in the United States. Sales of large cigars, which comprise about two-thirds of the total U.S. cigar market, increased 18 percent between 1996 and 1997. Consumption of premium cigars (mostly imported and hand-made) increased even more, an astounding 90 percent last year and an estimated 250 percent since 1993. In contrast, during this same time period, cigarette consumption declined 2 percent. This dramatic change in tobacco use raises a number of public health questions: Who is using cigars? What are the health risks? Are premium cigars less hazardous than regular cigars? What are the risks if you don't inhale the smoke? What are the health implications of being around a cigar smoker? In order to address these questions, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) undertook a complete review of what is known about cigar smoking and is making this information available to the American public. This monograph, number 9 in a series initiated by NCI in 1991, is the work of over 50 scientists both within and outside the Federal Government. Thirty experts participated in the multi-stage peer review process (see acknowledgments). -

USA Brief in Red Earth

Case: 10-3165 Document: 227 Page: 1 09/28/2010 114238 74 10-3165-cv 10-3191-cv 10-3213-cv IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT RED EARTH LLC, d/b/a SENECA SMOKESHOP, AARON J. PIERCE, SENECA FREE TRADE ASSOCIATION, Plaintiffs-Appellees/Cross-Appellants, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ERIC H. HOLDER, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the United States, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, JOHN E. POTTER, in his official capacity as Postmaster General and Chief Executive Officer of the United States Postal Service, UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE, Defendants-Appellants/Cross-Appellees. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK OPENING BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS/CROSS-APPELLEES [Counsel Listed On Following Page] Case: 10-3165 Document: 227 Page: 2 09/28/2010 114238 74 COUNSEL FOR DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS/CROSS-APPELLEES TONY WEST Assistant Attorney General WILLIAM J. HOCHUL, Jr. United States Attorney MARK B. STERN ALISA B. KLEIN MICHAEL P. ABATE (202) 616-8209 Attorneys, Appellate Staff Civil Division, Room 7318 Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 Case: 10-3165 Document: 227 Page: 3 09/28/2010 114238 74 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION. ....................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES. ............................................................................ 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE................................................................................. 2 STATEMENT OF FACTS. ...................................................................................... 5 I. Statutory Background........................................................................... 5 A. State and local excise taxes curb tobacco use, particularly underage use.. ......................................................... 5 B. The PACT Act addresses the problems presented by remote sales of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco................. 7 II. -

2020 NSDUH Final CAI Specifications for Programming

2020 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH (NSDUH): FINAL CAI SPECIFICATIONS FOR PROGRAMMING Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Rockville, Maryland 20857 Last Revised: October 31, 2019 2020 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH (NSDUH): FINAL CAI SPECIFICATIONS FOR PROGRAMMING Contract No. HHSS283201700002C RTI Project No. 0215638.020.019.102.001 RTI Authors: RTI Project Director: Emily Geisen David Hunter Gretchen McHenry Larry Kroutil SAMHSA Project Officer: Peter Tice For questions about this report, please email [email protected]. Prepared for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, Maryland Prepared by RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina Last Revised: October 31, 2019 Recommended Citation: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2019). 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): CAI Specifications for Programming (English Version). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. Acknowledgments This publication was developed for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ), by RTI International, a trade name of Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, under Contract No. HHSS283201700002C. Significant other contributors to this document at RTI include Rebecca Granger and David Hunter, who were reviewers. Contributors to this report from CBHSQ include Barbara Forsyth, Grace Medley, and Laura J. Sherman. Content of 2020 NSDUH Instrument # Module Mode of Administration Required Aids Page 1. Introduction CAPI* None 1 2. Core Demographics CAPI Showcards 1-5 3 3. Beginning ACASI Section FI reads description of keyboard and None 13 helps respondent adjust headphones. -

Restricted Flavored Tobacco Products

Restricted Flavored Tobacco Products BRAND PRODUCT FLAVOR 1839 FILTERED CIGAR BLACKBERRY 1839 FILTERED CIGAR CHERRY 1839 FILTERED CIGAR MENTHOL 1839 FILTERED CIGAR VANILLA 1839 MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 10/20 MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 10/20 LIGHTS MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 10/20 ULTRA LIGHTS MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 1839 GREEN MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 1839 LIGHTS MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 1ST CHOICE MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 1ST CHOICE LIGHTS MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 1ST CLASS MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 1ST CLASS GREEN MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 1ST CLASS LIGHTS MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 24/7 MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 24/7 GOLD MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 305'S FILTERED CIGAR MENTHOL 305'S MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 305'S GOLD MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL Page 1 of 180 09/28/2021 Restricted Flavored Tobacco Products DETAIL PUBLISHED DATE 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 08/07/2014 Page 2 of 180 09/28/2021 Restricted Flavored Tobacco Products 305'S LIGHTS MENTHOL-FLAVORED CIGARETTE MENTHOL 38 SPECIAL FILTERED CIGAR CHERRY 38 SPECIAL FILTERED CIGAR GRAPE 38 SPECIAL FILTERED CIGAR GRAPE 38 SPECIAL FILTERED CIGAR MENTHOL 38 SPECIAL FILTERED CIGAR PEACH 38 SPECIAL FILTERED CIGAR VANILLA 4 ACES PIPE TOBACCO MINT 4 KINGS CIGARILLO MANGO ACID -

2014 NSDUH Field Interviewer Manual September 2013 I Table of Contents Table of Contents (Continued)

2014 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH Field Interviewer Manual Field Interviewer Computer Manual Contract No. HHSS283201300001C Project No. 0213757 Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, Maryland 20857 Prepared by: Research Triangle Institute September 2013 Field Interviewer:__________________________________________ FI ID No:__________________ 2014 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH Field Interviewer Manual Contract No. HHSS283201300001C Project No. 0213757 Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, Maryland 20857 Prepared by: Research Triangle Institute September 2013 2014 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH Field Interviewer Manual Contract No. HHSS283201300001C Project No. 0213757 Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, Maryland 20857 Prepared by: Research Triangle Institute September 2013 Research Triangle Institute MISSION To improve the human condition by turning knowledge into practice. VISION To be the world’s leading independent research organization, recognized for solving critical social and scientific problems. VALUES Integrity - We perform with the highest ethical standards of individual and group honesty. We communicate openly and realistically with each other and with our clients. Excellence - We strive to deliver results with exceptional quality and value. Innovation - We encourage multidisciplinary collaboration, creativity and independent thinking in everything we do. Respect for the Individual - We treat one another fairly, with dignity and equity. We support each other to develop to our full potential. Respect for RTI - We recognize that the strength of RTI International lies in our commitment, collectively and individually, to RTI’s vision, mission, values, strategies and practices. Our commitment to the Institute is the foundation for all other organizational commitments. -

Spring 2007 Catalog

1 760 S. Delsea Drive, PO Box 1447 Vineland, New Jersey 08362-1447 Phone: 856-692-7425 Toll Free: 800-552-2639 Fax :800-443-2067 ORDER CATALOG Customer Number Customer Name Day of Delivery Street Address Date of Delivery City State Taken by Qty Item number Description Office Hours: 7:00 am - 4:00 pm Monday - Friday Showroom Hours: 8:30 am - noon, 1:00 pm - 4:30 pm Monday - Thursday 8:30 am - noon, 1:00 pm - 3:00 Fridays 1-800-934-3968 www.wecard.org L J Zucca, Inc. 2007 Spring Catalog 2 Table of Contents Pages Automotive Air Fresheners, Antifreeze, Gas Cans, Maps, Motor Oil, Starting Fluid, Windsh 72-73 Beverages 33-42 Bottle water, Carbonated drinks, Sports drinks, Juices, Cigars 9-14 Boxes, Little Cigars, Packs, Premium, Twin Packs Cigarettes 4-8 25's, 100's, 120's, Generic, King's, Non Filter, Premium, Specialty Confections - Candy 22-32 Candy - Concession, Fundraiser, Gum, King Size, Mints, Nostalgic, Novelty, Peg-bags, Regular, Wrapped, Un-wrapped Dairy 88-90 Butter, Cheese, Dinners, Juice, Meats, Puddings Food Service 47-49 Cappuccino Mixes, Coffee Service, Fountain Syrups, Gallon & Bulk Items Frozen 91-93 Bagels, Cakes, Dinners, Juice, Meats, Pizza, Vegetables, Waffles, Grocery 74-87 Baby Needs, Cookies, Coffee. Condiments, Cleaning items, Laundry supplies, Pasta, Pet Food, Rice, Tea, Vegetables General Merchandise 19-21 Batteries, Duct Tape, Phone Cards, Shoe Polish, Super Glue Health & Beauty Care 57-71 Aspirin, Cold & Cough remedies, Eye care, Shampoo, Toiletries Paper 49-56 Aluminum Foil, Cups, Napkins, Plates, Towels, Trash Bags, Toilet Tissues Snacks 43-46 Chips, Cookies, Meat Snacks, Nuts, Popcorn, Pretzels, Tobacco & Tobacco Accessories 15-18 L J Zucca, Inc. -

Controlled Substances Version 6.2

CALIFORNIA COMMISSION ON PEACE OFFICER STANDARDS AND TRAINING Basic Course Workbook Series Student Materials Learning Domain 12 Controlled Substances Version 6.2 THE MISSION OF THE CALIFORNIA COMMISSION ON PEACE OFFICER STANDARDS AND TRAINING IS TO CONTINUALLY ENHANCE THE PROFESSIONALISM OF CALIFORNIA LAW ENFORCEMENT IN SERVING ITS COMMUNITIES Basic Course Workbook Series Student Materials Learning Domain 12 Controlled Substances Version 6.2 © Copyright 2007 California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) All rights reserved. Published 1998 Revised August 2001 Revised January 2006 Revised January 2007 Workbook Update April 26, 2011 Corrected December 2016 Revised March 2019 This publication may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without prior written permission of the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, with the following exception: California law enforcement or dispatch agencies in the POST program, POST-certified training presenters, and presenters and students of the California basic course instructional system are allowed to copy this publication for non-commercial use. All other individuals, private businesses and corporations, public and private agencies and colleges, professional associations, and non-POST law enforcement agencies in-state or out-of- state may purchase copies of this publication, at cost, from POST as listed below: From POST’s -

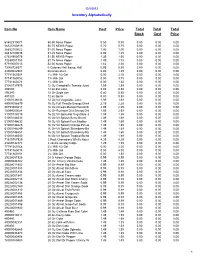

Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Stock Total

12/5/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 65652510071 $0.50 News Paper 0.50 0.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 56525100819 $0.75 NEWS Paper 0.70 0.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 26832100022 $1.00 News Paper 1.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 26832100039 $1.25 News Paper 0.00 1.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 67324900075 $1.50 NEWS Paper 1.35 1.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 73249001758 $1.75 News Paper 1.49 1.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 97910007013 $2.00 News Paper 1.82 2.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 13008728571 0 Calories Half & Half 0.99 0.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 44000022983 0reocakesters 0.80 1.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360304 1% Milk 1/2 Gal 0.00 2.15 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360052 1% Milk Gal 0.00 3.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360274 1% Milk Qrt. 0.00 1.30 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000137975 12 Oz Campbell's Tomato Juice 1.59 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 496580 12 oz diet coke 0.80 0.80 0.00 0.00 0.00 496340 12 Oz Soda can 0.80 0.80 0.00 0.00 0.00 491320 12 oz Sprite 0.80 0.80 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000138033 12 Oz V8 Vegetable Juice 1.59 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 49000036879 16 Oz Full Throttle Energy Drink 2.19 2.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 80793803613 16 Oz Omega Mango Passionfruit Energy 2.09 Drink 2.09 0.00 0.00 0.00 18094000024 16 Oz Rockstar Diet Energy Drink 1.55 2.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000138019 16 Oz V8 SpicyHot Vegetable Juice 1.59 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146533 16 Oz V8 Splash Berry Blend 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146632 16 Oz V8 Splash Fruit Medley 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146625 16 Oz V8 Splash Orange Pineapple 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146649 16 Oz V8 Splash Strawberry Banana 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146557 16 Oz V8 Splash Strawberry Kiwi 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146540 16 Oz V8 Splash Tropical Blend 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 71610757929 2 Pack Grenadiers Whiffs Natural Imported 4.29 Wrapper 4.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 23269142373 2 vanilla sunday fudge 1.29 1.89 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360168 2% Milk 1/2 Gal 0.00 2.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360014 2% Milk Gal 0.00 4.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360151 2% Milk Qrt. -

Controlled Substance Terminology

CALIFORNIA COMMISSION ON PEACE OFFICER STANDARDS AND TRAINING Basic Course Workbook Series Student Materials Learning Domain 12 Controlled Substances Version 6.1 THE MISSION OF THE CALIFORNIA COMMISSION ON PEACE OFFICER STANDARDS AND TRAINING IS TO CONTINUALLY ENHANCE THE PROFESSIONALISM OF CALIFORNIA LAW ENFORCEMENT IN SERVING ITS COMMUNITIES Basic Course Workbook Series Student Materials Learning Domain 12 Controlled Substances Version 6.1 © Copyright 2007 California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) All rights reserved. Published 1998 Revised August 2001 Revised January 2006 Revised January 2007 Workbook Update April 26, 2011 Corrected December 2016 This publication may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without prior written permission of the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, with the following exception: California law enforcement or dispatch agencies in the POST program, POST-certified training presenters, and presenters and students of the California basic course instructional system are allowed to copy this publication for non-commercial use. All other individuals, private businesses and corporations, public and private agencies and colleges, professional associations, and non-POST law enforcement agencies in-state or out-of- state may purchase copies of this publication, at cost, from POST as listed below: From POST’s Web Site: www.post.ca.gov -

Opens to Public Temple's

PAGE TWENTY THURSDAY, JULY 80, 19T0 . Average Daily Net Press Ron For Hie Wedc Ikided The Weather June 87. IMO hours at the home of Neoaroff’s Sunny, hot, humid through friend. Mafic Knee at 48 Madi About Town DAC Survey To Seek Ideas Sunday. Possible thunderstorms Nazaroff Takes Stand son St., Nasaroff and Miss Bret 15,610 in evenings. Low toni^t in 70s. on ate at the West Side Italian Miss Moira C. Dutton of Uyn- Kitchen. After leaving the res wood ,Dr., Bolton, Is studying For Educational Programs Hanchester— A City of Village Charni French at the Leyson American In His Own Defense taurant, Nasaroff decided to ed by volunteers from the Town look for his other car, a Valiant, School in Leyson, Switzerland. Beginning Monday, residents B y DOVO BEVIN8 Before her return to the United of Manchester will be asked to of Manchester, who will visit VOL. LXXXIX, NO. 256 (EIGHTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, JULY 31, 1970 (Classified Adverttsing tm Fage 16) PRICE TEN CENTS which had been missing for two families to be surveyed. All (Heimld B«potter) States, She plans to tour some participate in a town-wide drug days. Testifying that he sus those to be surveyed will be The malnslaughter trial of John Nazaroff of Man of the major European clUes. education survey sponsbred by pected that his wife had it, Nhs- contacted by telei^one and pos \ ■ri She is the daughter of Dr. and the Drug Advisory Council, and chester co n tin u e yesterday in H artford County Supe> aroff and Miss BreUm p r o c e tal card before they are visit rior Court, and Nazaroff took the witness stand in his ed to. -

2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health

2008 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH CAI Specifications for Programming English Version Contract No. 283-2004-00022 Project No. 9009 Prepared by: Research Triangle Institute Project Director: Tom Virag Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, Maryland 20857 November 2007 2008 NATIONAL SURVEY ON DRUG USE AND HEALTH CAI Specifications for Programming English Version Contract No. 283-04-00022 RTI Project No. 9009 Authors: Project Director: Jeanne Snodgrass Tom Virag Patty LeBaron Prepared for: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Rockville, MD 20857 Prepared by: RTI International November 2007 Content of 2008 NSDUH Instrument Module Mode of Administration Required Aids Page Changes to NSDUH Questionnaire NA None i Introduction CAPI* None 1 Core Demographics CAPI Showcards 1-4 3 Calendar FI reads instructions and identifies reference dates. Reference Date Calendar 9 (30-day and 12-month reference dates) FI reads description of keyboard and helps respondent adjust Beginning ACASI Section None 11 headphones. Tutorial Respondent completes computer practice session with FI help. None 13 Tobacco ACASI** None 15 Alcohol ACASI None 43 Marijuana ACASI None 53 Cocaine ACASI None 61 Crack ACASI None 69 Heroin ACASI None 77 Hallucinogens ACASI None 85 Inhalants ACASI None 115 Pain Relievers ACASI Pillcard A 125 Tranquilizers ACASI Pillcard B 137 Stimulants ACASI Pillcard C 145 Sedatives ACASI Pillcard D 157 Special Drugs ACASI None 165 Risk/Availability ACASI None 175 Blunts ACASI -

Preventing Initiation of Tobacco Use: Outcome Indicators for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs–2014

Preventing Initiation of Tobacco Use: Outcome Indicators for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs–2014 National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Division name here Acknowledgments This technical assistance guide was developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Office on Smoking and Health. This book was developed as the first part of a three part series of technical assistance guides intended to update the first three goal areas of the Key Outcome Indicators for Evaluating Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs, released in 2005. The guide is intended to help state and territorial health departments plan and evaluate state tobacco control programs. We would like to extend special thanks to the Expert Panel Members and Outcome Indicator Workgroup (Please see members listed in Appendix B) for their assistance in preparing and reviewing this publication. Online To download copies of this book, go to www.cdc.gov/tobacco or call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636). TTY: 1-888-232-6348 For More Information For more information about tobacco control and prevention, visit CDC’s Smoking & Tobacco Use Web site at http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco. Disclaimer Web site addresses of nonfederal organizations are provided solely as a service to readers. Provision of an address does not constitute an endorsement of this organization by CDC or the federal government, and none should be inferred. CDC is not responsible for the content of other organizations’ Web pages. Suggested Citation Preventing Initiation of Tobacco Use: Outcome Indicators for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs–2014. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014.