Introduction to Plant Life on Kent Ridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hillside Address City Living One of the Best Locations for a Residence Is by a Hill

Hillside Address City Living One of the best locations for a residence is by a hill. Here, you can admire the entire landscape which reveals itself in full glory and splendour. Living by the hill – a privilege reserved for the discerning few, is now home. Artist’s Impression • Low density development with large land size. • Smart home system includes mobile access smart home hub, smart aircon control, smart gateway with • Well connected via major arterial roads and camera, WIFI doorbell with camera and voice control expressways such as West Coast Highway and system and Yale digital lockset. Ayer Rajah Expressway. Pasir Panjang • International schools in the vicinity are United World College (Dover), Nexus International School, Tanglin Trust School and The Japanese School (Primary). • Pasir Panjang MRT station and Food Centre are within walking distance. • Established schools nearby include Anglo-Chinese School (Independent), Fairfield Methodist School and Nan Hua Primary School. • With the current URA guideline of 100sqm ruling in • Branded appliances & fittings from Gaggenau, the Pasir Panjang area, there will be a shortage of Bosch, Grohe and Electrolux. smaller units in the future. The master plan for future success 1 St James Power Station to be 2 Housing complexes among the greenery and A NUS and NUH water sports and leisure options. Island Southern Gateway of Asia served only by autonomous electric vehicles. B Science Park 3 Waterfront area with mixed use developments and C Mapletree Business City new tourist attractions, serves as extension of the Imagine a prime waterfront site, three times the size of Marina Bay. That is the central business district with a high-tech hub for untold potential of Singapore’s Master Plan for the Greater Southern Waterfront. -

WARTIME Trails

history ntosa : Se : dit e R C JourneyWARTIME into Singapore’s military historyTRAI at these lS historic sites and trails. Fort Siloso ingapore’s rich military history and significance in World War II really comes alive when you make the effort to see the sights for yourself. There are four major sites for military buffs to visit. If you Sprefer to stay around the city centre, go for the Civic District or Pasir Panjang trails, but if you have time to venture out further, you can pay tribute to the victims of war at Changi and Kranji. The Japanese invasion of February 1942 February 8 February 9 February 10 February 13-14 February 15 Japanese troops land and Kranji Beach Battle for Bukit Battle of Pasir British surrender Singapore M O attack Sarimbun Beach Battle Timah PanjangID Ridge to the JapaneseP D H L R I E O R R R O C O A H A D O D T R E R E O R O T A RC S D CIVIC DISTRICT HAR D R IA O OA R D O X T D L C A E CC1 NE6 NS24 4 I O Singapore’s civic district, which Y V R Civic District R 3 DHOBY GHAUT E I G S E ID was once the site of the former FORT CA R N B NI N CC2 H 5 G T D Y E LI R A A U N BRAS BASAH K O O W British colony’s commercial and N N R H E G H I V C H A A L E L U B O administrative activities in the C A I E B N C RA N S E B 19th and 20th century, is where A R I M SA V E H E L R RO C VA A you’ll find plenty of important L T D L E EY E R R O T CC3 A S EW13 NS25 2 D L ESPLANADE buildings and places of interest. -

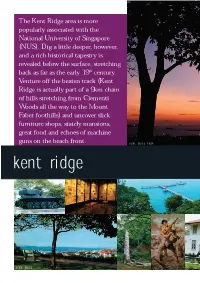

Kent Ridge Area Is More Popularly Associated with the National University of Singapore (NUS)

The Kent Ridge area is more popularly associated with the National University of Singapore (NUS). Dig a little deeper, however, and a rich historical tapestry is revealed below the surface, stretching back as far as the early 19 th century. Venture off the beaten track (Kent Ridge is actually part of a 9km chain of hills stretching from Clementi Woods all the way to the Mount Faber foothills) and uncover slick furniture shops, stately mansions, great food and echoes of machine guns on the beach front. KENT RIDGE PARK kent ridge KENT RIDGE west 2 3 Your first stop should be Kent Further south are the psychedelic Ridge Park (enter from South statues of Haw Par Villa (Pasir Buona Vista Road). Climb or jog Panjang Road). And moving to the top of the bluff for a eastwards is the superb museum, panoramic sweep of the ships Reflections at Bukit Chandu parked in the harbour far below. (31K Pepys Road), a two-storey The area is a regular haunt for bungalow that commemorates, fitness freaks out for their daily via stunning holographic and jog from the adjoining university. interactive shows, the Battle of If you have time, join the Bukit Chandu that was bravely fascinating eco-tours conducted led by a Malay regiment. by the Raffles Museum of Another popular destination in Biodiversity and Research the area is Labrador Park (enter REFLECTIONS AT BUKIT CHANDU (Block S6, Level 3, NUS). from Alexandra Road). Dating back to the 19 th century, the park was the site of a battlement guarding the island against invasion from the sea. -

List-Of-Bin-Locations-1-1.Pdf

List of publicly accessible locations where E-Bins are deployed* *This is a working list, more locations will be added every week* Name Location Type of Bin Placed Ace The Place CC • 120 Woodlands Ave 1 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Apple • 2 Bayfront Avenue, B2-06, MBS • 270 Orchard Rd Battery and Bulb Bin • 78 Airport Blvd, Jewel Airport Ang Mo Kio CC • Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Best Denki • 1 Harbourfront Walk, Vivocity, #2-07 • 3155 Commonwealth Avenue West, The Clementi Mall, #04- 46/47/48/49 • 68 Orchard Road, Plaza Singapura, #3-39 • 2 Jurong East Street 21, IMM, #3-33 • 63 Jurong West Central 3, Jurong Point, #B1-92 • 109 North Bridge Road, Funan, #3-16 3-in-1 Bin • 1 Kim Seng Promenade, Great World City, #07-01 (ICT, Bulb, Battery) • 391A Orchard Road, Ngee Ann City Tower A • 9 Bishan Place, Junction 8 Shopping Centre, #03-02 • 17 Petir Road, Hillion Mall, #B1-65 • 83 Punggol Central, Waterway Point • 311 New Upper Changi Road, Bedok Mall • 80 Marine Parade Road #03 - 29 / 30 Parkway Parade Complex Bugis Junction • 230 Victoria Street 3-in-1 Bin Towers (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Bukit Merah CC • 4000 Jalan Bukit Merah 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Bukit Panjang CC • 8 Pending Rd 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Bukit Timah Plaza • 1 Jalan Anak Bukit 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Cash Converters • 135 Jurong Gateway Road • 510 Tampines Central 1 3-in-1 Bin • Lor 4 Toa Payoh, Blk 192, #01-674 (ICT, Bulb, Battery) • Ang Mo Kio Ave 8, Blk 710A, #01-2625 Causeway Point • 1 Woodlands Square 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, -

Sipa One Hundred Sixty-Third Omnibus Objection: Exhibit A- No Liability Claims

08-01420-jmp Doc 7697 Filed 11/20/13 Entered 11/20/13 15:36:12 Main Document Pg 13 of 43 IN RE LEHMAN BROTHERS INC., CASE NO: 08-01420 (JMP) SIPA ONE HUNDRED SIXTY-THIRD OMNIBUS OBJECTION: EXHIBIT A- NO LIABILITY CLAIMS CLAIM TOTAL CLAIM TRUSTEE’S REASON FOR PROPOSED NAME / ADDRESS OF CLAIMANT DATE FILED NUMBER DOLLARS DISALLOWANCE 1 ANG, YAO WEN ALVIN 7001622 5/16/2009 $25,797.15 NO LEGAL OR FACTUAL JUSTIFICATION BLK 107 SPOTTISWOODE PARK ROAD FOR ASSERTING A CLAIM AGAINST LBI. #03-124 THE CLAIMED SECURITIES WERE NOT SINGAPORE 080107 ISSUED OR GUARANTEED BY LBI. SINGAPORE 2 BEE, TEO YAN 4727 5/26/2009 $50,000.00 NO LEGAL OR FACTUAL JUSTIFICATION 26 JALAN ARNAP FOR ASSERTING A CLAIM AGAINST LBI. SINGAPORE 249332 THE CLAIMED SECURITIES WERE NOT SINGAPORE ISSUED OR GUARANTEED BY LBI. 3 BENG, TAN WEE 4886 5/28/2009 UNSPECIFIED* NO LEGAL OR FACTUAL JUSTIFICATION 51 SIANG KUANG AVE FOR ASSERTING A CLAIM AGAINST LBI. SINGAPORE 348014 THE CLAIMED SECURITIES WERE NOT SINGAPORE ISSUED OR GUARANTEED BY LBI. 4 BENSON, LIM GHEE BOON 7002178 5/28/2009 $10,000.00 NO LEGAL OR FACTUAL JUSTIFICATION 57 HUME AVE #09-10 FOR ASSERTING A CLAIM AGAINST LBI. SINGAPORE 598753 THE CLAIMED SECURITIES WERE NOT SINGAPORE ISSUED OR GUARANTEED BY LBI. 5 BIN IBRAHIM, MOHAMED RASHID 4792 5/27/2009 $10,000.00 NO LEGAL OR FACTUAL JUSTIFICATION BLK 295C COMPASSVALE CRESCENT #04-243 FOR ASSERTING A CLAIM AGAINST LBI. SINGAPORE 543295 THE CLAIMED SECURITIES WERE NOT SINGAPORE ISSUED OR GUARANTEED BY LBI. -

Singapore Geology

Probabilistic Assessment of Engineering Rock Properties in Singapore for Cavern Feasibility by ARCHIVES MASSACHUSETTS 1NSTITI TE Chin Soon Kwa OF TECHNOLOLGY B.Eng. Civil Engineering JUL 02 2015 National University of Singapore, 2010 LIBRARIES SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2015 2015 Chin Soon Kwa. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author:......... ...................................................... Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 21, 2015 Certified by:............ ................................ Herbert H. Einstein Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor .a I A, - Accepted by: ........................ Signature redacted.......... Heidi Nepf Donald and Martha Harleman Professor of Civil and Environmental Enginering Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students .I I ! Probabilistic Assessment of Engineering Rock Properties in Singapore for Cavern Feasibility by Chin Soon Kwa Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 21, 2015, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT Singapore conducted various cavern studies since the 1990s, and has since constructed two caverns. The study done in this thesis concentrates on an area of interest within South-Western Singapore, using four logged boreholes that are each 200 meters in depth. Through the use of the empirical methods, the RQD and Q-system, rock support can be estimated for different ground classes for an assumed cavern size. -

Sius2018 J U L Y S U M M E R I N S T I T U T E I N 2 0 1 8 U R B a N S T U D I E S

1 5 - 1 9 #SIUS2018 J U L Y S U M M E R I N S T I T U T E I N 2 0 1 8 U R B A N S T U D I E S Programme Booklet Hosted by the Global Urban Studies Cluster, FASS, National University of Singapore WELCOME TO SIUS 2018 Welcome to Singapore and welcome to the 2018 Summer Institute in Urban Studies! This is the fourth SIUS, and the first in Singapore – indeed, the first to be hosted outside Manchester. The three previous Institutes held in 2014, 2015 and 2016 were a great success, and we have every expectation that SIUS 2018 will be just as intellectually and personally stimulating. While a variety of disciplinary and thematic summer events are well established, SIUS was the first to take aim at the inter-disciplinary field that is urban studies. That was the original rationale for the Institute. For as we move through the 21st century, which has been referred to by some as the “urban age”, so we are faced with intellectual challenges to which any single discipline seems inadequate. Conceptually and methodologically, making sense of our own bits of the urban puzzle – whether that is climate change, energy, infrastructure, housing or migration to name but five issues with which many cities are currently wrestling – demands we look beyond the disciplines in which we have each been trained. Anthropologists, architects, economists, engineers, environmentalists, geographers, historians, linguists, medics, planners, political scientists, sociologists; those working on the cities of the future are many, their intellectual backgrounds varied. -

Compelling Reasons to Buy Kent Ridge Hill Residences

Over 50% Sold! 10 Compelling Reasons To Buy Kent Ridge Hill Residences Undervalued Circle Line 6 mins walk MRT Unit Size Ruling High Rental Yield Excellent Location GSW Feng Shui Upside Potential Star buy Discount 360 Drone view Virtual Tours Disclaimer. While every effort has been made to update & ensure the accuracy of the data & comments contained as above in this presentation, please ensure that you conduct your own financial checks & analysis before embarking on any investments. ERA Realty Network Pte Ltd accepts no lability whatsoever for any errors, inaccuracies or omissions and shall not be bound in any manner by any information contained in this worksheet presentation. No information shall be construed as advice and no financial and/or investment decision should be made on the basis on the information provided. Kent Ridge Hill Residences is undervalued ENJOY INSTANT APPRECIATION IN PROPERTY VALUE JUST BY BUYING KENT RIDGE HILL RESIDENCES. BUYERS ENJOY UP TO 5% DISCOUNT! Undervalued Circle Line 6 mins walk MRT Unit Size Ruling High Rental Yield Excellent Location GSW Feng Shui Upside Potential Star buy Discount 360 Drone View Virtual Tours Home MRT Circle Line Enhance Accessibility The Circle Line (CCL) will become a full circle in 2025, when a 4km rail stretch with three new stations - Keppel, Cantonment and Prince Edward – is completed. CCL6 will link existing terminal stations HarbourFront and Marina Bay, offering commuters direct routes to the city and Marina Bay area. "CCL6 will support direct east-west travel, enhancing overall connectivity between areas such as Paya Lebar and Mountbatten, and areas such as Pasir Panjang, Kent Ridge and HarbourFront," said Acting Minister for Education (Schools) and Senior Minister of State for Transport Ng Chee Meng, who unveiled the new stations during a visit to the Tuas West Extension on 29 October. -

Science Park Space Inserts Final.FH11

The Rutherford Science Park Space Location Address 89 Science Park Drive The Rutherford, Singapore Science Park I Singapore 118261 Accessibility Within 5-min drive from the National University of Singapore (NUS) A 15-min drive from the CBD and from Clementi or Buona Vista MRT stations A 5-min walk to bus stop with bus no. 92 and Science Park shuttle service Building Specifications Type of Building 4-storey building with 3 main lobbies at each storey Type of Premises Research units: Fitted units ideal for any R&D activities The Singapore Science Park is Asia-Pacifics from software development and most prestigious address for R&D and IT set-ups technology, unique for its lushly landscaped Total Lettable Floor Area grounds and unrivalled for its high quality Approx. 15,623.26 sqm facilities and services. Situated along Floor Loading Singapores Technology Corridor, the 1st storey : 10 KN/sqm Parks campus-like setting provides the 2nd - 4th storey : 7.5 KN/sqm ideal working environment for more Floor to Floor Height than 260 MNCs, local companies and Floor to Ceiling : 4.5 m Floor to underside of beam : 3.6 m research organisations. Door Size 1st storey : 2.35 m x 1.79 m 2nd storey : 2.125 m x 1.45 m www.ascendas.com N Mechanical and Electrical Provisions To North Buona Vista Road, 1 passenger lift and I service lift on each floor of Buona Vista MRT and Holland Village each lobby Kent Ridge Road 4 aircon duct risers and 1 data riser on each floor 2 floor traps per unit for 1st - 3rd storey units, 1 floor trap per unit for 4th storey -

Singapore Raptor Report February 2017

Singapore Raptor Report February 2017 Chinese Sparrowhawk, adult female, Ang Mo Kio, 17 Feb 2017, by Tan Gim Cheong. Summary for migrant species: In February, 66 individuals of 7 migrant species were recorded. While the 26 Oriental Honey Buzzards were similar to last February's numbers, the 19 Black Bazas represented a drop of more than half compared to last February. All the Black Bazas were recorded at the Punggol - Pasir Ris - Tampines area. Six Jerdon's Baza were recorded, five at Punggol on the 4th and one at Pasir Ris Park on the 12th, good numbers for this species. Of the six Peregrine Falcons recorded, two adults were photographed fighting at Seletar Airport vicinity on the 27th. Three Japanese Sparrowhawks were recorded; two of them, adult males, on the 6th at Changi Business Park and 10th at Bidadari, showed signs of moult, similar to what was observed last February, and had only 4 'fingers' instead of the usual 5 'fingers'. Five Ospreys were recorded, including three over Bukit Timah Hill on the 20th. Two Chinese Sparrowhawks were recorded, one at Kent Ridge Park on the 2nd and another, an adult female, at Ang Mo Kio on the 5th, 17th and 19th. A Crested Serpent Eagle photographed at Kent Ridge Park on the 10th by Gavan Leong turned out to be a 3rd year burmanicus, thanks to Dr Chaiyan for his expertise. This is the second occurrence of the burmanicus form, a short distance migrant from Indo-China, to Singapore. The previous record was in September and November 2014 when an individual was photographed at the Japanese Gardens. -

Advanced Robotics Center Open House National University of Singapore 30 May 2017 (Tuesday), 6.00Pm to 9.00Pm

Advanced Robotics Center Open House National University of Singapore 30 May 2017 (Tuesday), 6.00pm to 9.00pm Come to see the cool robots and meet the talented people behind them at our open house! Take a ride on our self-driving vehicles, see a selfie with our drone camera, try out our soft robotics prototypes, and witness our robots in action! Light refreshment will be served. Registration The event is complimentary, but please pre-register here to help us plan for the logistics and prepare for your arrival. When: 30 May 2017 (Tuesday), 6.00pm to 9.00pm Where: Advanced Robotics Center (ARC), National University of Singapore How to get there? By Taxi (about S$20, 20 minutes without traffic each way) The approximate taxi fare is S$20. It takes about 20 mins without traffic. Instructions to the taxi driver: Take AYE, exit Clementi Road, and enter NUS through the first entrance on the Clementi Road. See the Google map below for the location of Advanced Robotics Center. By MRT Train (about S$ 1.40, 35 minutes each way) • From the Bayfront Station (DT16) on the Downtown Line (Blue), board the train towards Bukit Panjang Station and alight at Botanic Gardens MRT Station (DT9), 7 stops later. • Change to the Circle Line (Orange), board the train towards Harbourfront Station and alight at Kent Ridge MRT Station (CC24), 5 stops later. • Exit the Station via the Entrance A. There is free shuttle service that takes you to the Advanced Robotics Centre directly. Pick-up point is at Bus Stop 3 at Kent Ridge MRT station via Entrance A. -

Consolidated Lockers Locations List

Page 1 of 18 Postal sector Location name Address (first-two digits) Parcel Santa - The Sail @Marina Bay 4 Marina Boulevard Singapore 018986 01 bluPort - Marina Bay Link Mall 8A Marina Boulevard #B2-80 Singapore 018984 bluPort - CityLink Mall 1 Raffles Link #B1-K8 Singapore 039393 bluPort - Millenia Walk 9 Raffles Boulevard #B1-K1 Singapore 039596 03 Park n Parcel - Nomi Japan @ Marina Square 6 Raffles Boulevard #02-219A, Marina Square Singapore 039594 Park n Parcel - Perfect Fit @ Citylink Mall One Raffles Link #B1-10A, Citylink Mall Singapore 039393 bluPort - The Arcade 11 Collyer Quay Singapore 048620 04 bluPort - One Raffles Quay 1 Raffles Quay Singapore 048583 Park n Parcel - Mercury @ The Arcade 11 Collyer Quay #01-30, The Arcade Singapore 049317 Parcel Santa - Trevose Park 531 Upper Cross Street Singapore 050531 05 Park n Parcel - Spectrum Store @ Clarke Quay Central 6 Eu Tong Sen St, #01-43 Singapore 059817 06 bluPort - Frasers Tower 182 Cecil Street Singapore 069547 Parcel Santa - 76 Shenton 76 Shenton Way Singapore 079119 07 Parcel Santa - Skysuites @Anson 8 Enggor Street Singapore 079718 08 Parcel Santa - Spottiswoode 18 18 Spottiswoode Park Road Singapore 088642 Parcel Santa - Caribbean @ Keppel Bay 2 Keppel Bay Drive Telok Blangah, Singapore 098636 Parcel Santa - Reflections at Keppel Bay 25 Keppel Bay View Singapore 098415 Parcel Santa - Seascape @Sentosa Cove 55 Cove Way, Singapore 098307 Parcel Santa - The Azure 201 Ocean Drive Singapore 098584 Parcel Santa - The Berth By The Cove 228 Ocean Drive #01-34 Singapore 098616