Justices, 5-4, Reject Corporate Spending Limit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

34-05-HR Haldeman

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Contested Materials Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 34 5 8/2/1972Campaign Memo From Higby to Strachan RE: talking paper for the Ehrlichman political action group. 3 pgs. 34 5 Campaign Report Talking paper for Ehrlichman political group. 2 pgs. 34 5 7/17/1972Campaign Memo From Hainsworth to Dent RE: Texas. 1 pg. 34 5 7/14/1972Campaign Memo From Hainsworth to Dent RE: California. 4 pgs. Friday, June 19, 2015 Page 1 of 4 Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 34 5 7/28/1972Campaign Memo From Malek and Magruder to MacGregor RE: Staffing of Command Post Off Convention Floor. 3 pgs. 34 5Campaign Other Document Handwritten notes (author unk) RE: Camp Session. 2 pgs. 34 5 7/12/1972Campaign Other Document State Chairman meeting agenda, Mayflower Hotel. 1 pg. 34 5 7/12/1972Campaign Other Document From CRP RE: State Chairman Meeting, the Mayflower Hotel. 2 pgs. 34 5 7/12/1972Campaign Other Document State Chairman Meeting Agenda, The Mayflower Hotel. 1 pg. Friday, June 19, 2015 Page 2 of 4 Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 34 5Campaign Other Document Handwritten notes (author unk) RE: Cal - FM. 1 pg. 34 5 7/18/1972Campaign Memo From Malek to Strachan RE: State budgets. 20 pgs. 34 5 7/21/1972Campaign Memo From Malek to MacGregor RE: Establishment of Educators and Teachers for the Re-Election of the President. -

President Richard Nixon's Daily Diary, May 16-31, 1973

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Air Force One – Appendix “B” 5/19/1973 A 2 Manifest Air Force One – Appendix “D” 5/25/1973 A 3 Log Key Biscayne, Florida – 6:40 p.m. – p 2 5/26/1973 A of 2 Sanitized 6/2000 OPENED 06/2013 4 Manifest Air Force One – Appendix “B” 5/28/1973 A 5 Manifest Air Force One – Appendix “B” 5/30/1973 A 6 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/19/1973 A Appendix “A” 7 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/20/1973 A Appendix “A” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-12 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary May 16, 1973 – May 31, 1973 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Frederic V. Malek Papers, White House Central Files, 1969-1974

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8jd4xf4 Online items available Frederic V. Malek Papers, White House Central Files, 1969-1974 1969-1974 Frederic V. Malek Papers, White 3599960 1 House Central Files, 1969-1974 Descriptive Summary Title: Frederic V. Malek Papers, White House Central Files, 1969-1974 Dates: 1969-1974 Collection Number: 3599960 Creator/Collector: Malek, Frederic V. (Frederic Vincent), 1936- Extent: 13 linear feet, 7 linear inches; 31 boxes Online items available http://research.archives.gov/description/3599960 Repository: Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum Abstract: The materials of Frederic Malek encompass the years 1969 to 1973, and relate to Malek’s roles as deputy undersecretary of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) (1969 to late 1970) and head of the White House Personnel Operation (WHPO) (late 1970 to 1973). Language of Material: English Access Collection is open for research. Some materials may be unavailable based upon categories of materials exempt from public release established in the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act of 1974. Publication Rights Most government records are in the public domain; however, this series includes commercial materials, such as newspaper clippings, that may be subject to copyright restrictions. Researchers should contact the copyright holder for information. Preferred Citation Frederic V. Malek Papers, White House Central Files, 1969-1974. Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum Acquisition Information These materials are in the custody of the National Archives and Records Administration under the provisions of Title I of the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-526, 88 Stat. 1695) and implementing regulations. -

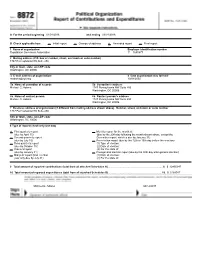

Initial Report Change of Address ✔ Amended Report Final Report

A For the period beginning 01/01/2016 and ending 03/31/2016 B Check applicable box: Initial report Change of address ✔ Amended report Final report 1 Name of organization Employer identification number Republican Governors Association 11 - 3655877 2 Mailing address (P.O. box or number, street, and room or suite number) 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 3 E-mail address of organization: 4 Date organization was formed: [email protected] 10/04/2002 5a Name of custodian of records 5b Custodian's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 6a Name of contact person 6b Contact person's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 7 Business address of organization (if different from mailing address shown above). Number, street, and room or suite number 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 8 Type of report (check only one box) ✔ First quarterly report Monthly report for the month of: (due by April 15) (due by the 20th day following the month shown above, except the Second quarterly report December report, which is due by January 31) (due by July 15) Pre-election report (due by the 12th or 15th day before the election) Third quarterly report (1) Type of election: (due by October 15) (2) Date of election: Year-end report (3) For the state of: (due by January 31) Post-general election report (due by the 30th day after general election) Mid-year report (Non-election (1) Date of election: year only-due by July 31) (2) For the state of: 9 Total amount of reported contributions (total from all attached Schedules A) .......................................................................... -

The New York Times > Magazine > in the Magazine Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush

The New York Times > Magazine > In the Magazine: Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush 7/31/10 9:19 AM TimesPeople NYTimes: Home - Site Index - Archive - Help Go to a Section Site Search: NYTimes.com > Magazine IN THE MAGAZINE Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush By RON SUSKIND Published: October 17, 2004 Correction Appended Bruce Bartlett, a domestic policy adviser to Ronald Reagan and a treasury official for the first President Bush, told me recently that ''if Bush wins, there will be a civil war in the Republican Party starting on Nov. 3.'' The nature of that conflict, as Bartlett sees it? Essentially, the same as the one raging across much of the world: a battle between modernists and fundamentalists, pragmatists and true believers, reason and religion. ''Just in the past few months,'' Bartlett said, ''I think a light has gone off for people who've spent time up close to Kevin LaMarque/Reuters Bush: that this instinct he's always talking about is this sort of weird, Messianic idea of what he thinks God has ARTICLE TOOLS told him to do.'' Bartlett, a 53-year-old columnist and Printer-Friendly Format self-described libertarian Republican who has lately been Most E-Mailed Articles a champion for traditional Republicans concerned about Bush's governance, went on to say: ''This is why George W. Bush is so clear-eyed about Al Qaeda and the Islamic fundamentalist enemy. He believes you have to kill them all. They can't be persuaded, that they're extremists, driven by a dark vision. -

Interview with John Borling # VRV-A-L-2013-037.05 Interview # 05: April 23, 2014 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with John Borling # VRV-A-L-2013-037.05 Interview # 05: April 23, 2014 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Wednesday, April 23, 2014. My name is Mark DePue, Director of Oral History with the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. Today, once again, I’m in Rockford, Illinois with General John Borling. Good morning, Sir. Borling: Good morning to you. Spring is almost here, although it was thirty-three degrees when I ran this morning. I went out in shorts and ended up with red legs and watching other people come bundling down the path, looking like it was midwinter again, although it looks to be a pleasant day. -

Virginia Influencers

VirginiaInfluencers he once reliably red state of Virginia has developed the hint of a purplish hue and become something of a swing state. TThe GOP has come back with a vengeance over the last two years, yet in the preceding two decades, Ol’ Virginny became the first state to select an African American as governor, elected two Demo- cratic chief executives, and helped send Barack Obama to the White House. Indeed, the 2008 election marked the first time in forty-four years that the state awarded its electoral votes to a Democratic presi- dential candidate. While that contest ended one trend, the next year’s election con- tinued another one. Since 1977, Virginia has elected its one-term gov- ernor from the party opposite that of the sitting president. And, due to its unique election cycle—Virginia holds its gubernatorial contests in off-off years—voters can express their shifting sentiments at the polls every year. Here is our list of the most influential political players in Virginia— with no elected officials allowed. VirginiaInfluencers Top 10 Democrats Timothy M. Kaine David Mills Mo Elleithee The former governor helped Democrats The executive director of the Virginia A founding partner of Hilltop Public take control of the state Senate in 2007 Democratic Party has worked in the Solutions in Washington, D.C., Elleithee and elect Barack Obama president the Kaine administration and on several gu- has been a key consultant to Virginia following year. Kaine, an attorney and bernatorial campaigns. Mills is married Democrats such as Kaine and U.S. Sen. former Richmond mayor, served as to Jennifer McClellan, a rising young Mark Warner and is a veteran of several chairman of the national Democratic member of the state House. -

The Once Reliably Red State of Virginia Has Developed the Hint of a Purplish

HE once reliably red state of Virginia has developed the hint of A purplish hue and become something of A swing state. TThe GOP has come back with A vengeance over the last two years, yet in the preceding two decades, 01' Virginny became the first state to select an African American as governor, elected two Demo- cratic CHIEF executives, and helped send Barack Obama to the White House. Indeed, the 2008 election marked the first time in forty-four years that the state awarded its electoral votes to A Democratic presi- dential candidate. While that contest ended one trend, the next year's election con- tinued another one. Since 1977, Virginia has elected its one-term gov- ernor from the party opposite that of the sitting president. And, DuE to its unique election cycle--Virginia holds its gubernatorial contests in off-off years-voters can express their shilling sentiments at the polls every year. Here is our list of the most influential political players in Virginia- with no elected officials allowed. Top 10 Republicans ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Phil Cox Cox deserves as much credit as any- one for the 2009 election of Gov. Bob McDonnell. The political strategist and consultant is sought after as an advisor by campaigns outside Virginia and re- mains the governor's top political man. He is now executive director of the Re- publican Governors Association. Chris LaCivita In Virginia, he's known simply as LaCi- vita. And, while he may be anonymous to much of the public, his work isn't. LaCivita is a campaign consultant and was a key media advisor involved in the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth ads at- tacking 2004 Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry. -

The Power 100

SPECIAL FEATURE | the PoweR 100 THE POWER 100 The brains behind the poltical players that shape our nation, the media minds that shape our opinions, the developers who revitalize our region, and the business leaders and philanthropists that are always pushing the envelope ... power, above all, is influence he Washington socialite-hostess gathers the ripe fruit of These things by their very nature cannot remain static – political, economic, and cultural orchards and serves it and therefore our list changes with the times. Tup as one fabulous cherry bombe at a charity fundraiser Power in Washington is different than in other big cities. or a private soirée with Cabinet secretaries and other major Unlike New York, where wealth-centric power glitters with political players. Two men shake hands in the U.S. Senate and the subtlety of old gold, wealth doesn’t automatically confer a bill passes – or doesn’t. The influence to effect change, be it power; in Washington, rather, it depends on how one uses it. in the minds or actions of one’s fellow man, is simultaneously Washington’s power is fundamentally colored by its the most ephemeral quantity (how does one qualify or rate proximity to politics, and in this presidential season, even it?) and the biggest driving force on our planet. more so. This year, reading the tea leaves, we gave a larger nod In Washington, the most obvious source of power is to the power behind the candidates: foreign policy advisors, S È political. However, we’ve omitted the names of those who fundraisers, lobbyists, think tanks that house cabinets-in- draw government paychecks here, figuring that it would waiting, and influential party leaders. -

The Candidates

The Candidates Family Background Bush Gore Career Highlights Bush Gore Personality and Character Bush Gore Political Communication Lab., Stanford University Family Background USA Today June 15, 2000; Page 1A Not in Their Fathers' Images Bush, Gore Apply Lessons Learned From Losses By SUSAN PAGE WASHINGTON -- George W. Bush and Al Gore share a reverence for their famous fathers, one a former president who led the Gulf War, the other a three-term Southern senator who fought for civil rights and against the Vietnam War. The presidential candidates share something else: a determination to avoid missteps that brought both fathers repudiation at the polls in their final elections. The younger Bush's insistence on relying on a trio of longtime and intensely loyal aides -- despite grumbling by GOP insiders that the group is too insular -- reflects his outrage at what he saw as disloyalty during President Bush's re-election campaign in 1992. He complained that high- powered staffers were putting their own agendas first, friends and associates say. Some of those close to the younger Gore trace his willingness to go on the attack to lessons he learned from the above-the-fray stance that his father took in 1970. Then-senator Albert Gore Sr., D-Tenn., refused to dignify what he saw as scurrilous attacks on his character with a response. The approach of Father's Day on Sunday underscores the historic nature of this campaign, as two sons of accomplished politicians face one Political Communication Lab., Stanford University another. Their contest reveals not only the candidates' personalities and priorities but also the influences of watching their famous fathers, both in victory and in defeat. -

David Hume Kennerly Archive Project

DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE PROJECT 50 YEARS BEHIND THE SCENES OF HISTORY The David Hume Kennerly Archive is an extraordinary collection of images, objects and recollections created and collected by a great American photographer, journalist, artist and historian documenting 50 years of United States and world history. The goal of the DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE PROJECT is to protect, organize and share its rare and historic objects – and to transform its half-century of images into a cutting- edge digital educational tool that is fully searchable and available to the public for research and artistic appreciation. 2 DAVID HUME KENNERLY Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist David Hume Kennerly has spent his career documenting the people and events that have defined the world. The last photographer hired by Life Magazine, he has also worked for Time, People, Newsweek, Paris Match, Der Spiegel, Politico, ABC, NBC, CNN and served as Chief White House Photographer for President Gerald R. Ford. Kennerly’s images convey a deep understanding of the forces shaping history and are a peerless repository of exclusive primary source records that will help educate future generations. His collection comprises a sweeping record of a half-century of history and culture – as if Margaret Bourke-White had continued her work through the present day. 3 HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE The David Hume Kennerly collection of photography, historic artifacts, letters and objects might be one of the largest and most historically significant private collections ever produced and collected by a single individual. Its 50-year span of images and objects tells the complete story of the baby boom generation. -

Independent Expenditures and Electioneering Communication Expenditures Reported to the Federal Election Commission

March 2013 www.citizen.org October 24, 2012 Super Connected Outside Groups’ Devotion to Individual Candidates and Political Parties Disproves the Supreme Court’s Key Assumption in Citizens United That Unregulated Outside Spenders Would Be ‘Independent’ (UPDATED VERSION OF OCTOBER 2012 REPORT, WITH REVISED DATA AND DISCUSSION OF THE ‘SOFT MONEY’ IMPLICATIONS OF CITIZENS UNITED) Acknowledgments This report was written by Taylor Lincoln, research director of Public Citizen’s Congress Watch division. Congress Watch Legislative Assistant Kelly Ngo assisted with research. Congress Watch Director Lisa Gilbert edited the report. Public Citizen Litigation Group Senior Attorney Scott Nelson provided expert advice. This report draws in part on a May 2012 amicus brief to the Supreme Court that was coauthored by Nelson. About Public Citizen Public Citizen is a national non-profit organization with more than 300,000 members and supporters. We represent consumer interests through lobbying, litigation, administrative advocacy, research, and public education on a broad range of issues including consumer rights in the marketplace, product safety, financial regulation, worker safety, safe and affordable health care, campaign finance reform and government ethics, fair trade, climate change, and corporate and government accountability. Public Citizen’s Congress Watch 215 Pennsylvania Ave. S.E Washington, D.C. 20003 P: 202-546-4996 F: 202-547-7392 http://www.citizen.org © 2013 Public Citizen. Public Citizen Super Connected Methodology and Definitions . This report represents a substantial update of a report published in October 2012, available at http://www.citizen.org/documents/super-connected-candidate-super-pacs-not- independent-report.pdf. Most of the data used in this report was drawn from the Center for Responsive Politics (www.opensecrets.org) or the Sunlight Foundation (http://sunlightfoundation.com).