Icc-01/18-45 14-02-2020 1/12 Ek Pt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt-Israel Peace Liad Porat

102 e Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt-Israel Peace Liad Porat [email protected] www.besacenter.org THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 102 The Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt-Israel Peace Liad Porat © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel http://www.besacenter.org ISSN 0793-1042 January 2014 The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies advances a realist, conservative, and Zionist agenda in the search for security and peace for Israel. It was named in memory of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, whose efforts in pursuing peace lay the cornerstone for conflict resolution in the Middle East. The center conducts policy-relevant research on strategic subjects, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel and Middle East regional affairs. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author’s views or conclusions. Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center for the academic, military, official and general publics. In sponsoring these discussions, the BESA Center aims to stimulate public debate on, and consideration of, contending approaches to problems of peace and war in the Middle East. The Policy Memorandum series consists of policy-oriented papers. -

2021 International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust

Glasses of those murdered at Auschwitz Birkenau Nazi German concentration and death camp (1941-1945). © Paweł Sawicki, Auschwitz Memorial 2021 INTERNATIONAL DAY OF COMMEMORATION IN MEMORY OF THE VICTIMS OF THE HOLOCAUST Programme WEDNESDAY, 27 JANUARY 2021 11:00 A.M.–1:00 P.M. EST 17:00–19:00 CET COMMEMORATION CEREMONY Ms. Melissa FLEMING Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mr. António GUTERRES United Nations Secretary-General H.E. Mr. Volkan BOZKIR President of the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly Ms. Audrey AZOULAY Director-General of UNESCO Ms. Sarah NEMTANU and Ms. Deborah NEMTANU Violinists | “Sorrow” by Béla Bartók (1945-1981), performed from the crypt of the Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris. H.E. Ms. Angela MERKEL Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany KEYNOTE SPEAKER Hon. Irwin COTLER Special Envoy on Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Antisemitism, Canada H.E. Mr. Gilad MENASHE ERDAN Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations H.E. Mr. Richard M. MILLS, Jr. Acting Representative of the United States to the United Nations Recitation of Memorial Prayers Cantor JULIA CADRAIN, Central Synagogue in New York El Male Rachamim and Kaddish Dr. Irene BUTTER and Ms. Shireen NASSAR Holocaust Survivor and Granddaughter in conversation with Ms. Clarissa WARD CNN’s Chief International Correspondent 2 Respondents to the question, “Why do you feel that learning about the Holocaust is important, and why should future generations know about it?” Mr. Piotr CYWINSKI, Poland Mr. Mark MASEKO, Zambia Professor Debórah DWORK, United States Professor Salah AL JABERY, Iraq Professor Yehuda BAUER, Israel Ms. -

Dr. Irwin Cotler, MP

Dr. Irwin Cotler, MP Irwin Cotler, PC, OC, MP, Ph.D. (born May 8, 1940) was Canada's Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada from 2003 until the Liberal government of Paul Martin lost power following the 2006 federal election. He was first elected to the Canadian House of Commons for the constituency of Mount Royal in a by-election in November 1999, winning over 91% of votes cast. He was sworn into Cabinet on December 12, 2003. The son of a lawyer, he was born in Montreal, Quebec, studied at McGill University there (receiving a BA in 1961 and a law degree three years later) and then continued his education at Yale University. For a short period, he worked with federal Minister of Justice John Turner. Cotler was a professor of law at McGill University and the director of its Human Rights Program from 1973 until his election as a Member of Parliament in 1999 for the Liberal Party of Canada. He has also been a visiting professor at Harvard Law School, a Woodrow Wilson Fellow at Yale Law School and is the recipient of five honorary doctorates. He was appointed in 1992 as an Officer of the Order of Canada. He is a past president of the Canadian Jewish Congress. Human Rights Cotler has served on the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and its sub-Committee on Human Rights and International Development, as well as on the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. In 2000, he was appointed special advisor to the Minister of Foreign Affairs on the International Criminal Court. -

December 2009 the SENIOR TIMES Validation: a Special Understanding Photo: Susan Gold the Alzheimer Groupe Team Kristine Berey Rubin Says

Help Generations help kids generationsfoundation.com O 514-933-8585 DECEMBER2009 www.theseniortimes.com VOL.XXIV N 3 Share The Warmth this holiday season FOR THE CHILDREN Kensington Knitters knit for Dans la rue Westhill grandmothers knit and Montreal Children’s Hospital p. 21 for African children p. 32 Editorial DELUXE BUS TOUR NEW YEAR’S EVE Tory attack flyers backfire GALA Conservative MPs have upset many Montrealers Royal MP Irwin Cotler has denounced as “close to Thursday, Dec 31 pm departure with their scurrilous attack ads, mailed to peo- hate speech.”The pamphlet accuses the Liberals of Rideau Carleton/Raceway Slots (Ottawa) ple with Jewish-sounding names in ridings with “willingly participating in the overly anti-Semitic significant numbers of Jewish voters. Durban I – the human rights conference in South Dance the Night Away • Eat, Drink & be Merry Live Entertainment • Great Buffet There is much that is abhorrent about the tactic Africa that Cotler attended in 2001 along with a Casino Bonus • Free Trip Giveaway itself and the content. Many of those who received Canadian delegations. In fact, Cotler, along with Weekly, Sat/Sun Departures the flyer are furious that the Conservatives as- Israeli government encouragement, showed sume, falsely, that Canadian Jews base their vote courage and leadership by staying on, along with CALL CLAIRE 514-979-6277 on support for Israel, over and above the commu- representatives of major Jewish organizations, in nity members’ long-standing preoccupation with an effort to combat and bear witness to what Lois Hardacker social justice, health care, the environment and a turned into an anti-Israel and anti-Semitic hate Royal LePage Action Chartered Broker host of other issues. -

Leadership Talk by the Chair of the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights

IrwinCotler Leadership Talk by the Chair of the Raoul WallenbergCentre forHuman Rights The fight against antisemitism is part of alargercommon cause that bringsus together—the struggle against racism, against hate,against antisemitism, against massatrocity,and against the crime whose name we should even shud- der to mention, namelygenocide. And mostly, and here Ireference my mentor and teacher Elie Wiesel, against indifference and inaction in the face of injustice and antisemitism;and all this is part of the largerstruggle for justice, for peace, and human rights in our time.¹ As it happens, the conference “An End to Antisemitism!” took place at an importantmoment of remembrance and reminder of bearing witness and taking action.Ittook place in the aftermath of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, remindingofhorrors tooterrible to be believed but not too terrible to have happened. Of the Holocaust,asElie Wiesel would remind us again and again; of awar against the Jews in which “not all victims wereJews, but all Jews werevictims.”² The conference “An End to Antisemitism!” also took place on the seventieth anniversary year,moving towards both the Genocide Convention and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Genocide Convention was called the “Never-Again-Convention,” but after it,genocidehas occurred again and again. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, being the Magna Charter of the UN,asformer UN secretary-gen- eral Kofi Annan said, “emergesfrom the ashes of the Holocaust intended to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war.”³ Both bears thatreminder today, that aUNthat fails to be at the forefront at of the struggle against antisem- itism and other forms of racism, deniesits history and undermines its future. -

Why Europe Abolished Capital Punishment

Why Europe Abolished Capital Punishment John Quigley* and S. Adele Shank** “Whatever may be the conclusion of this night of this House, no doubt arises that the punishment must pass away from our land, and that at no distant date capital punishment will no longer exist. It belongs to a much earlier day than ours, and it is no longer needed for the civilization of the age in which we live.”1 J.W. Pease, a member of the House of Commons, made this declaration in London in 1877.2 Pease, an industrialist and a Quaker, was speaking in support of a bill he proposed to abolish capital punishment in the United Kingdom. Pease’s bill was voted down.3 Consequently, capital punishment would remain in British law into the twentieth century.4 Pease’s sentiment, however, reflected what would be the consensus position in Europe a century later. Capital punishment would come to be seen as antithetical to the values of a civilized society. Europe’s path to that position, however, would be far from uniform. In the early nineteenth century, capital punishment was universal in Europe.5 Later in the century, a few countries in Western Europe abolished it.6 The issue was part of a larger discussion about criminal law. A reaction against severity in the administration of justice had taken hold in Europe. Influential in European thinking was the work of an Italian lawyer who included capital * John Quigley is a President’s Club Professor Emeritus of Law at the Michael E. Moritz College of Law. -

Reforming the Supreme Court Appointment Process, 2004-2014: a 10-Year Democratic Audit 2014 Canliidocs 33319 Adam M

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 67 (2014) Article 4 Reforming the Supreme Court Appointment Process, 2004-2014: A 10-Year Democratic Audit 2014 CanLIIDocs 33319 Adam M. Dodek Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Dodek, Adam M.. "Reforming the Supreme Court Appointment Process, 2004-2014: A 10-Year Democratic Audit." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 67. (2014). http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol67/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Reforming the Supreme Court Appointment Process, 2004-2014: A 10-Year Democratic Audit* Adam M. Dodek** 2014 CanLIIDocs 33319 The way in which Justice Rothstein was appointed marks an historic change in how we appoint judges in this country. It brought unprecedented openness and accountability to the process. The hearings allowed Canadians to get to know Justice Rothstein through their members of Parliament in a way that was not previously possible.1 — The Rt. Hon. Stephen Harper, PC [J]udicial appointments … [are] a critical part of the administration of justice in Canada … This is a legacy issue, and it will live on long after those who have the temporary stewardship of this position are no longer there. -

Children: the Silenced Citizens

Children: The Silenced Citizens EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION OF CANADA’S INTERNATIONAL OBLIGATIONS WITH RESPECT TO THE RIGHTS OF CHILDREN Final Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights The Honourable Raynell Andreychuk Chair The Honourable Joan Fraser Deputy Chair April 2007 Ce document est disponible en français. This report and the Committee’s proceedings are available online at www.senate-senat.ca/rights-droits.asp Hard copies of this document are available by contacting the Senate Committees Directorate at (613) 990-0088 or by email at [email protected] Membership Membership The Honourable Raynell Andreychuk, Chair The Honourable Joan Fraser, Deputy Chair and The Honourable Senators: Romeo Dallaire *Céline Hervieux-Payette, P.C. (or Claudette Tardif) Mobina S.B. Jaffer Noël A. Kinsella *Marjory LeBreton, P.C. (or Gerald Comeau) Sandra M. Lovelace Nicholas Jim Munson Nancy Ruth Vivienne Poy *Ex-officio members In addition, the Honourable Senators Jack Austin, George Baker, P.C., Sharon Carstairs, P.C., Maria Chaput, Ione Christensen, Ethel M. Cochrane, Marisa Ferretti Barth, Elizabeth Hubley, Laurier LaPierre, Rose-Marie Losier-Cool, Terry Mercer, Pana Merchant, Grant Mitchell, Donald H. Oliver, Landon Pearson, Lucie Pépin, Robert W. Peterson, Marie-P. Poulin (Charette), William Rompkey, P.C., Terrance R. Stratton and Rod A. Zimmer were members of the Committee at various times during this study or participated in its work. Staff from the Parliamentary Information and Research Service of the Library of Parliament: -

Global Antisemitism: Assault on Human Rights

1 Global Antisemitism: Assault on Human Rights Irwin Cotler Member of Canadian Parliament Former Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada Professor of Law, McGill University [email protected] The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series. Working Paper Cotler 2009 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISBN: 978-0-9819058-4-6 Series Editor Charles Asher Small ISGAP ������������������������������������������������������������������ New York, NY 10022 United States Ofce Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org 2 ABSTRACT Reecting on the global resurgence of antisemitism, Nobel Peace Laureate Elie Wiesel commented as follows: “[May I] share with you the feeling of urgency, if not, emergency, that we believe Antisemitism represents and calls for. I must confess to you, I have not felt the way I feel now since 1945. I feel there are reasons for us to be concerned, even afraid … now is the time to mobilize the efforts of all of humanity.” Indeed, what we are witnessing today – and which has been developing incrementally, sometimes imperceptibly, and even indulgently, for some thirty-ve years now is an old/ new, sophisticated, globalizing, virulent, and even lethal Antisemitism, reminiscent of the atmospherics of the 30s, and without parallel or precedent since the end of the Second World War. -

Robert Badinter Confrontation Entre Ce Qu’Il a De Plus Stimulant

LI 181:Mise en page 1 05/05/2010 11:25 Page 1 A VOUS DE LIRE ! NUIT DES MUSÉES ORSAY NOUVELLE 3000 LIEUX 300 LYCÉENS INITIATIVE D’EXPOSITION DIALOGUENT CANNES, SHANGHAI 2010... EN FAVEUR OUVERTS EN AVEC ROBERT COMMENT DE LA LECTURE EUROPE BADINTER LA FRANCE « EXPORTE » SA CULTURE CULTURECOMMUNICATION LE MAGAZINE DU MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE ET DE LA COMMUNICATION / MAI 2010 N° 181 TAPIS ROUGE ET PHOTOGRAPHES : LES RITUELS DU FESTIVAL DE CANNES REPRENNENT À PARTIR DU 12 MAI. SUR NOTRE PHOTO : ISSN : 1255-6270 LE CINÉASTE WONG KAR WAI ET L’ÉQUIPE DE SON FILM EN 2007 (DÉTAIL) © AFP PHOTO / FRED DUFOUR / POOL LI 181:Mise en page 1 05/05/2010 11:25 Page 2 LE TEMPS FORT ACTUALITÉS Shanghai 2010 et Festival de Cannes Comment la France « exporte » sa culture PARTICIPATION À L’EXPOSITION UNIVERSELLE DE SHANGHAI, ORGANISATION DU FESTIVAL DE CANNES… ENMAI, LA CULTURE FRANÇAISE VA SE MOBILISER SUR LA SCÈNE INTERNATIONALE. NE ville meilleure pour une meilleure vie ». C’est sur ce thème – placé sous le signe du déve- loppement durable mais aussi du plaisir de vivre dans les villes – que l’Exposition universelle de « Shanghai a ouvert ses portes le 1er mai. Pendant six mois,U elle va présenter, via des pavillons nationaux, la diversité des principales richesses – entre innovations et traditions – de 192 pays, dont 31 pays africains et 50 organisations internationales, ce qui constitue un record inégalé de participants à une Exposition universelle. Autre chiffre considérable : celui du nombre de visi- teurs prévus. Pour l’édition 2010, pas moins de 70 à 100 millions © AFP PHOTO / FRED DUFOUR POOL © sont attendus jusqu’au 31 octobre, soit deux à trois fois plus que pour la précédente édition qui s’est tenue en 2005 au Japon. -

The August 2015 Issue of Inside Policy

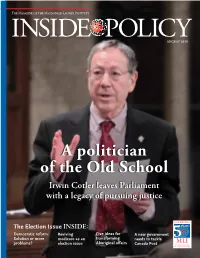

AUGUST 2015 A politician of the Old School Irwin Cotler leaves Parliament with a legacy of pursuing justice The Election Issue INSIDE: Democratic reform: Reviving Five ideas for A new government Solution or more medicare as an transforming needs to tackle problems? election issue Aboriginal affairs Canada Post PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley, byCrowley, the Managing Macdonald-LaurierManaging Director,Director, [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames Anderson,Managing Anderson, Editor ManagingManaging and Editor, Editor,Communications Inside Inside Policy Policy Director Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:writers: Editor, Inside Policy Past contributors ThomasThomas S. AxworthyS. Axworthy ContributingAndrewAndrew Griffith writers: BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. AxworthyDonald Barry Laura Dawson Stanley H. HarttCarin Holroyd Mike Priaro Peggy Nash DonaldThomas Barry S. Axworthy StanleyAndrew H. GriffithHartt BenjaminMike PriaroPerrin Mary-Jane Bennett Elaine Depow Dean Karalekas Linda Nazareth KenDonald Coates Barry PaulStanley Kennedy H. Hartt ColinMike Robertson Priaro Carolyn BennettKen Coates Jeremy Depow Paul KennedyPaul Kennedy Colin RobertsonGeoff Norquay Massimo Bergamini Peter DeVries Tasha Kheiriddin Benjamin Perrin Brian KenLee Crowley Coates AudreyPaul LaporteKennedy RogerColin Robinson Robertson Ken BoessenkoolBrian Lee Crowley Brian -

50-Year Case of Election Fever

Help Generations help kids generationsfoundation.com O 514-933-8585 OCTOBER2008 theseniortimes.com VOL.XXIIIN 1 INSIDE Dancing duo makes ‘em smile p. 7 50-year case of election Cotler frustrated by fever inaction on Darfur p. 11 p. 3 She needs you! p. 13 Editorial: Strong candidates make voting decisions tough With storm clouds signaling economic meltdown for the NDP, Conservatives and Green Party who son is waging a high-profile campaign. Former as- hovering over the United States,the debates in the are attracting attention and would make excellent tronaut Marc Garneau is the Liberal star candidate Canadian general election seemed liked a passing MPs. Green Party leader Elizabeth May urges there – certainly a man of honour and achievement, sunshower.Addtothatthedramaof Obamaversus Canadians to vote with their hearts, but some are who has proved his dedication to the common good. McCain,and his risky choice of Sarah Palin as run- calling for strategic voting, to support whomever The NDP’s Peter Deslauriers, former head of the ning mate,and you have all the makings of drama, is strongest to prevent a Tory majority. Dawson College teachers’ union, is also an attrac- even if at times it resembled a daytime soap opera. Some may feel that Liberal leader Stéphane Dion, tive candidate for NDG–Lachine, up against Mar- But we have a real battle going on right here, an honest, hardworking, principled and brilliant lene Jennings, who has become a well-known with all the opinion surveys pointing to a renewed man, has been pilloried for not being as good with advocate of minority rights.