Bruwer Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History 1886

How many bones must you bury before you can call yourself an African? Updated December 2009 A South African Diary: Contested Identity, My Family - Our Story Part D: 1886 - 1909 Compiled by: Dr. Anthony Turton [email protected] Caution in the use and interpretation of these data This document consists of events data presented in chronological order. It is designed to give the reader an insight into the complex drivers at work over time, by showing how many events were occurring simultaneously. It is also designed to guide future research by serious scholars, who would verify all data independently as a matter of sound scholarship and never accept this as being valid in its own right. Read together, they indicate a trend, whereas read in isolation, they become sterile facts devoid of much meaning. Given that they are “facts”, their origin is generally not cited, as a fact belongs to nobody. On occasion where an interpretation is made, then the commentator’s name is cited as appropriate. Where similar information is shown for different dates, it is because some confusion exists on the exact detail of that event, so the reader must use caution when interpreting it, because a “fact” is something over which no alternate interpretation can be given. These events data are considered by the author to be relevant, based on his professional experience as a trained researcher. Own judgement must be used at all times . All users are urged to verify these data independently. The individual selection of data also represents the author’s bias, so the dataset must not be regarded as being complete. -

Module 3 Gauteng

Tel: +27 11 676 3000 | Web: www.guideacademy.co.za Module 3 Gauteng Gauteng Province GAUTENG ........................................................................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION - TRANSVAAL .......................................................... 7 PHYSICAL FEATURES AND BOUNDARIES ........................................................................................... 7 HISTORY ......................................................................................................................................... 7 The Early Inhabitants ................................................................................................................ 7 Early Europeans ........................................................................................................................ 8 Important dates ......................................................................................................................... 8 GAUTENG ECONOMY ..................................................................................................................... 11 Manufacturing ......................................................................................................................... 11 Basic facts and statistics ......................................................................................................... 11 Mining ..................................................................................................................................... -

Rhodesian Sunset Factional Politics, War, and the Demise of an Imperial Order in British South Africa

Rhodesian Sunset Factional Politics, War, and the Demise of an Imperial Order in British South Africa By Michael Brunetti A thesis submitted to the Department of History for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina Under the advisement of Dr. Vasant Kaiwar April 15, 2019 Brunetti | i Abstract The pursuit of an unorthodox and revolutionary grand vision of empire by idealistic imperialists such as Cecil Rhodes, Alfred Milner, and Percy FitzPatrick led to the creation of a pro-conflict imperial coalition in South Africa, one that inadvertently caused the South African War. This thesis examines the causes behind the South African War (also known as the Second Anglo-Boer War), sheds light on those culpable for its occurrence, and analyzes its effects on South Africa’s subsequent failure to fulfill the imperial vision for it held by contemporary British imperialists. This thesis addresses the previous historiographical debates on the relative importance of the factions that formed a coalition to promote their interests in South Africa. Some of these interests focused on political and economic matters of concern to the British Empire, while others pertained to Johannesburg settlers, primarily of British extraction, who had their own reasons for joining the pro-imperial coalition. Moreover, this thesis emphasizes the importance of the pro-imperial coalition’s unity in provoking the South African War while also explaining the coalition’s post-war decline and directly correlating this to the decline of British influence in South Africa. Brunetti | ii Acknowledgments To Dr. Vasant Kaiwar, for being my advisor, my gateway to the Duke University History Department, my mentor, and my friend. -

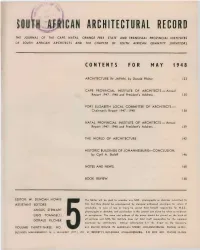

Architectural Record

ARCHITECTURAL RECORD THE JOURNAL OF THE CAPE. NATAL. ORANGE FREE STATE AND TRANSVAAL PROVINCIAL INSTITUTES OF SOUTH AFRICAN ARCHITECTS AND THE CHAPTER OF SOUTH AFRICAN QUANTITY SURVEYORS CONTENTS FOR MAY 1948 A R C H IT E C T U R E IN J A P A N , by Donald Pilcher 123 CAPE PROVINCIAL INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS — Annuel Report 1947- 1948 and President's Address 135 PORT ELIZABETH LOCAL COMMITTEE OF ARCHITECTS — Chairman's Report 1947 - 1948 I38 NATAL PROVINCIAL INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS — Annual Report 1947 - 1948 and President’s Address 139 THE WORLD OF ARCHITECTURE I42 HISTORIC BUILDINGS OF JOHANNESBURG— CONCLUSION, by C yril A . S to lo ff 146 NOTES AND NEWS 160 BOOK REVIEW 160 EDITOR: W. DUNCAN HOWIE The Editor will be glad to consider any MSS., photographs or sketches submitted to ASSISTANT EDITORS: him, but they should be accompanied by stamped addressed envelopes tor return if unsuitable. In case of loss or injury he cannot hold himself responsible for M.S.S., ANGUS STEWART photographs or sketches, and publication in the Journal can alone be taken as evidence UGO TOMASELLI of acceptance. The name and address of the owner should be placed on the back of all pictures and M SS. The Institute does not hold itself responsible for the opinions DORALD PILCHER expressed by contributors. Annual subscription E l l 10s. direct to the Secretary. VOLUME THIRTY-THREE. NO. 612, KELVIN HOUSE. 75, MARSHALL STREET, JOHANNESBURG. PHONE 34-292I. B U SIN E SS M ANAG EM ENT: G. J. M cHARRY (PTY.) LTD., 43, BEC KETT'S BU ILD IN G S, JO HA N N ESBURG . -

July 2018, a Queensland Others: AGM Concerning NBWMA (Queensland) and the Continuation Of

National Boer War Memorial Association National Patron: Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin AC Chief of the Defence Force Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO, RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 11, No. 3 Queensland Chairman’s Report Welcome to our third Queensland Newsletter of 2018. Since our ‘Piper Joe’ (Joe McGhee), provided pipe music before the last newsletter, a lot has happened; such as the planning and co- service, whilst warming his pipes up. The Scouts lowered ordination of the ‘Boer War Day Commemoration Service - 2018’ the flags to half-mast, to the sound of ‘Going Home’, As mentioned in our last Newsletter, the planned renovations and played by ‘Piper Joe’; a piper’s tribute to the fallen. refurbishment works of ANZAC Square, in the vicinity of, and in- The address by our Queensland Patron cluding the Boer War Memorial, by the BCC (Brisbane City Coun- MAJGEN John Pearn AO, GCStJ, RFD, cil), very much influenced our planning and co-ordination process. added a special touch to the service. This meant we had to re-plan the ‘Boer War Commemoration Ser- vice’. Therefore, the ‘Boer War Day Commemoration Service’ of Corinda State High School and Aspley 2018, was held at the ‘Shrine of Remembrance’ and ‘Eternal State High School played important Flame’, Ann Street end of ANZAC Square, on Sunday, 27th May at roles in the service. The Corinda 10:00 hours. State High School Symphonic Band, provided music before, during and The ‘Boer War Day Commemoration Service’ turned out to be a after the service. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE RANDLORDS AND FIGURATIONS: AN ELIASIAN STUDY OF SOCIAL CHANGE AND SOUTH AFRICA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD (Sociology) By Jacques Human The University of Edinburgh 2018 LAY SUMMARY This study investigates the role that the Randlords, a group of mining magnates with wide-ranging concerns operating in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, played in social change in South Africa. The way of thinking about this is in terms of figurations, or groups of people who have a shared purpose and tend to stick together. It also develops a way of understanding and drawing conclusions from letters and old documents. The First Randlord investigated was George Farrar, and it was found that many Randlords had different goals and views, but many did share the views of goals of a colonial administrator called Alfred Milner. -

Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality Heritage

CATALOGUE NO: AR-5 DATE RECORDED: July 2003/February 2004 __________________________________________________________________ JOHANNESBURG METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY HERITAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEYING FORM __________________________________________________________________ Compiled by: Dr JJ Bruwer, 2002-07-29 JJ Bruwer © Cellphone: 082 325 5823 NAME OF PLACE: UNION CLUB BUILDING Previous/alternative name/s : Union Club Flats _____________________________________________________________________________ AR-5 1 LOCATION: Street : Bree Street number : 244 : [242, 244 Bree; 67, 69 Joubert] Stand Number : 1256, 1257, 1258, RE/1255 Previous Stand Number: originally - 1018, 1019, 1020, RE/1017 Block number : AR GIS reference : ZONING: Current use/s : Previous use/s : DESCRIPTION OF PLACE: Height : Levels above street level : originally three-storeys Levels below street level : none On-site parking : none Authors’ note: A detailed architectural history of the building remains outstanding on account of its incomplete plans record. Of particular concern is the fact that the plans of the additional storeys of the building are missing. This is a common predisposition in the case of buildings designed by eminent architects such as Baker & Fleming. It is also quite noticeable that only plans of ‘lesser importance’ have escaped the attention of the responsible wrongdoers. “Long ago at the Cape Baker had not hesitated to use the most economical and efficient modern building methods that were then available in South Africa when he built multi-story (sic.) office blocks. He had done the same at the Union Club, the Pretoria Station and the Union Buildings…” (Doreen E. Greig, D. E.: Herbert Baker…) Van Der Waal not only describes, but also compares various aspects of the Union Club Building with those of the YMCA Building: “The YMCA makes a rather tentative statement in the Neo-Georgian style because the formal relationships are underemphasized. -

Provisioning Johannesburg, 1886 – 1906

PROVISIONING JOHANNESBURG, 1886 – 1906 by ELIZABETH ANN CRIPPS submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: Professor E J Carruthers JOINT SUPERVISOR: Professor J Hyslop February 2012 (i) PROVISIONING JOHANNESBURG, 1886 – 1906 (ii) by Elizabeth Ann Cripps (iii) MA (iv) History (v) Professor E J Carruthers (vi) Professor J Hyslop (vii) The rapidity of Johannesburg’s growth after the discovery of payable gold in 1886 created a provisioning challenge. Lacking water transport it was dependent on animal-drawn transport until the railways arrived from coastal ports. The local near-subsistence agricultural economy was supplemented by imported foodstuffs, readily available following the industrialisation of food production, processing and distribution in the Atlantic world and the transformation of transport and communication systems by steam, steel and electricity. Improvements in food preservation techniques: canning, refrigeration and freezing also contributed. From 1895 natural disasters ˗ droughts, locust attacks, rinderpest, East Coast fever ˗ and the man-made disaster of the South African War, reduced local supplies and by the time the ZAR became a British colony in 1902 almost all food had to be imported. By 1906, though still an import economy, meat and grain supplies had recovered, and commercial agriculture was responding to the market. (viii) KEY WORDS: Johannesburg, ZAR, Food Supply, Railways, Market, Grains, Meat, Vegetables, Fruit, English-speakers, Africans, Distribution, Transvaal Colony CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION: SOURCES, BACKGROUND AND SCOPE 1 2. JOHANNESBURG FOOD SUPPLY IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT 15 3. SOUTH AFRICAN PRODUCED FOOD: THE REPUBLICAN YEARS 36 4. -

THE POWER BEHIND the PRESS English Newspapers in The

THE POWER BEHIND THE PRESS English Newspapers in The Transvaal, 1870-1899 By Cynthia A. Robinson B.A., The University of New Mexico A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 1989 ©Cynthia A. Robinson, 1989 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) THE POWER BEHIND THE PRESS: ABSTRACT The thesis explores the question of whether the Johannesburg English newspapers, and particularly The Johannesburg Star, were manipulated or were independent during the volatile years leading up to the outbreak, of the Second Boer War. Historians and contemporaries alike have argued that the editorial policy of the Star was dictated by either the mining magnates of the Rand or the imperial officials. This study approaches the question by first surveying the history of English newspapers in the Transvaal. It follows the history of the press from the early diamond boom days in Kimberley in the 1870s, through the Barberton gold rush, and on to the founding and growth of the Johannesburg papers. -

The Evolution of Research Collaboration in South African Gold Mining: 1886-1933

The Evolution of Research Collaboration in South African Gold Mining: 1886-1933 PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Maastricht, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, Prof. mr. G.P.M.F. Mols, volgens het besluit van het College van Decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 29 juni 2006 om 16.00 uur door Thomas Edwin Pogue Promotores: Prof. dr. R. Cowan Prof. dr. N. Nattrass (University of Cape Town) Co-promotor: Prof. dr. D. Kaplan (University of Cape Town) Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. dr. C. de Neubourg (voorzitter) Prof. dr. E. Homburg Prof. dr. F. Wilson (University of Cape Town) Copyright © Thomas E. Pogue, Johannesburg 2006 Production: Datawyse / Universitaire Pers Maastricht TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MAPS.....................................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF FIGURES.............................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................................................... iv ABBREVIATIONS................................................................................................................................................v CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION