Acting Shakespeare a Roundtable Discussion with Artists from the Utah Shakespearean Festival’S 2007 Production of King Lear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

Saluting the Classical Tradition in Drama

SALUTING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ILLUMINATING PRESENTATIONS BY The Shakespeare Guild IN COLLABORATION WITH The National Arts Club The Corcoran Gallery of Art The English-Speaking Union Woman’s National Democratic Club KATHRYN MEISLE Monday, February 6 KATHRYN MEISLE has just completed an extended run as Deborah in ROUNDABOUT THEATRE’s production of A Touch of the Poet, with Gabriel Byrne in the title part. Last year she delighted that company’s audiences as Marie-Louise in a rendering of The Constant Wife that starred Lynn Redgrave. For her performance in Tartuffe, with Brian Bedford and Henry Goodman, Ms. Meisle won the CALLOWAY AWARD and was nominated for a TONY as Outstanding Featured Actress. Her other Broadway credits include memorable roles in London Assur- NATIONAL ARTS CLUB ance, The Rehearsal, and Racing Demon. Filmgoers will recall Ms. Meisle from You’ve Got Mail, The Shaft, and Rosewood. Home viewers 15 Gramercy Park South Manhattan will recognize her for key parts in Law & Order and Oz. And those who love the classics will cherish her portrayals of such heroines as Program, 7:30 p.m. Celia, Desdemona, Masha, Olivia at ARENA STAGE, the GUTHRIE THEATER, MEMBERS, $25 OTHERS, $30 LINCOLN CENTER, the NEW YORK SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL, and other settings. E. R. BRAITHWAITE Thursday, February 23 We’re pleased to welcome a magnetic figure who, as a young man from the Third World who’d just completed a doctorate in physics from Cambridge, discovered to his consternation that the color of his skin prevented him from landing a job in his chosen field. -

Britain, Canada and the Arts -- Major International, Interdisciplinary Conference

H-Announce CFP: Britain, Canada and the Arts -- Major International, Interdisciplinary Conference Announcement published by Irene Morra on Tuesday, August 9, 2016 Type: Call for Papers Date: June 15, 2017 Location: United Kingdom Subject Fields: British History / Studies, Canadian History / Studies, Cultural History / Studies, Humanities, Theatre & Performance History / Studies Britain, Canada, and the Arts: Cultural Exchange as Post-war Renewal 15-17 June 2017 CALL FOR PAPERS Papers are invited for a major international, interdisciplinary conference to be held at Senate House, London, in collaboration with ENCAP (Cardiff University) and the University of Westminster. Coinciding with and celebrating the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation, this conference will focus on the strong culture of artistic exchange, influence, and dialogue between Canada and Britain, with a particular but not exclusive emphasis on the decades after World War II. The immediate post-war decades saw both countries look to the arts and cultural institutions as a means to address and redress contemporary post-war realities. Central to the concerns of the moment was the increasing emergence of the United States as a dominant cultural as well as political power. In 1951, the Massey Commission gave formal voice in Canada to a growing instinct, amongst both artists and politicians, simultaneously to recognize a national tradition of cultural excellence and to encourage its development and perpetuation through national institutions. This moment complemented a similar post-war engagement with social and cultural renewal in Britain that was in many respects formalized through the establishment of the Arts Council of Great Britain. It was further developed in the founding of such cultural institutions as the Royal Opera, Sadler’s Wells Ballet, the Design Council and later the National Theatre, and in the diversity and expansion of television and film. -

Group Sales Tickets

SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY 21st Annual Table of Contents D.C.’s favorite Feature Letter from Michael Kahn 5 The Two Faces of Capital summer by Drew Lichtenberg 6 Program Synopsis 11 theatre event About the Playwright 13 Title Page 15 Cast 17 is back! Cast Biographies 18 PRESENTED BY Direction and Design Biographies 22 Shakespeare Theatre Company Tickets will be available Board of Trustees 8 online and in line! Shakespeare Theatre Company 26 Individual Support 28 Visit ShakespeareTheatre.org/FFA for more details on how to get your tickets via lottery Corporate Support 40 or at Sidney Harman Hall on the day of the Foundation and performance. Tickets for 2011–2012 Season Government Support 41 subscribers available through the Box Office Academy for Classical Acting 41 beginning July 5, 2011, at 10 a.m. For the Shakespeare Theatre Company 42 Join the Friends of Free Staff 44 JULIUS For All for tickets! Audience Services 50 Free For All would not be possible without Creative Conversations 50 CAESAR the hundreds of individuals who generously donate to support the program each year. “ Only with the help of the Friends of Free For All is STC able to offer free performances, All hail Julius Caesar! making Shakespeare accessible to … One of the best productions of this or any season.” Washington, D.C., area residents every summer. The Washingtonian In appreciation for this support, Friends of Free For All receive exclusive benefits during This Year's Production: the festival such as reserved Free For All tickets, the option to have tickets mailed in August 18–September 4 advance, special event invitations, program recognition and more. -

FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini

Pat McCorkle, CSA Jeffrey Dreisbach, Casting Partner Katja Zarolinski, CSA Kristen Kittel, Casting Assistant FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini. Starring: William Shatner, Christopher Lloyd, Jean Smart. THE MURPHYS (Independent Feature; Producer(s): The Murphy's LLC). Director: Kaitlan McGlaughlin. BERNARD & HUEY (In production. Independent Feature; Producer(s): Dan Mervish/Bernie Stein). Director: Dan Mervish. AFTER THE SUN FELL (Post Production. Independent feature; Producer(s): Joanna Bayless). Director: Tony Glazer. Starring: Lance Henriksen, Chasty Ballesteros, Danny Pudi. FAIR MARKET VALUE (Post Production. Feature ; Producer(s): Judy San Romain). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Jerry Adler, D.C. Anderson, Michael J. Arbouet. YEAR BY THE SEA (Festival circuit. Feature; Producer(s): Montabella Productions ). Director: Alexander Janko. Starring: Karen Allen, Yannick Bisson, Michael Cristofer. CHILD OF GRACE (Lifetime Network Feature; Producer(s): Empathy + Pictures/Sternamn Productions). Director: Ian McCrudden. Starring: Ted Lavine, Maggy Elizabeth Jones, Michael Hildreth. POLICE STATE (Independent Feature; Producer(s): Edwin Mejia\Vlad Yudin). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Sean Young, Seth Gilliam, Christina Brucato. MY MAN IS A LOSER (Lionsgate, Step One Entertainment; Producer(s): Step One of Many/Imprint). Director: Mike Young. Starring: John Stamos, Tika Sumpter, Michael Rapaport. PREMIUM RUSH (Columbia Pictures; Producer(s): Pariah). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. JUNCTION (Movie Ranch; Producer(s): Choice Films). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. GHOST TOWN* (Paramount Pictures; Producer(s): Dreamworks SKG). Director: David Koepp. Starring: Ricky Gervais, Tea Leoni, Greg Kinnear. WAR EAGLE (Empire Film; Producer(s): Downstream Productions). Director: Robert Milazzo. Starring: Brian Dennehy, Mary Kay Place, Mare Winningham. -

By Amy Freed

SC 53rd Season • 510th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / MAY 5 - JUNE 4, 2017 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents The MONSTER BUILDER by Amy Freed Thomas Buderwitz Angela Balogh Calin Kent Dorsey SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN Rodolfo Ortega Ken Merckx Ursula Meyer ORIGINAL MUSIC AND SOUNDSCAPE FIGHT CHOREOGRAPHER DIALECT COACH Joshua Marchesi Joanne DeNaut, CSa Lora K. Powell PRODUCTION MANAGER CASTING STAGE MANAGER Directed by Art Manke Timothy & Marianne Kay Jean & Tim Weiss Honorary Producers Honorary Producers The Monster Builder • South CoaSt RepeRtoRy • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Gregor .................................................................................................. Danny Scheie Tamsin .................................................................................................. Annie Abrams Rita .............................................................................. Susannah Schulman Rogers Dieter ................................................................................................. Aubrey Deeker Pamela .................................................................................................. Colette Kilroy Andy ................................................................................................ Gareth Williams SETTING In and around a major American city. LENGTH Approximately two hour and 10 minutes, including 20-minute one intermission. PRODUCTION -

Gielgud 2006

A Toast to Shakespeare and to the Recipient of the 2006 GIELGUD AWARD A GALA AT WHICH THE GOLDEN QUILL For the charming caricatures of Sir John Gielgud in his various roles IS BESTOWED UPON CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER that adorn the back cover of this keepsake, The Shakespeare Guild is deeply grateful to CLIVE FRANCIS, a multitalented London actor who has given us such sprightly publications as LAUGH LINES, SIR JOHN: MONDAY, JUNE 12, AT 6:30 P.M. THE MANY FACES OF GIELGUD, and THERE IS NOTHING LIKE A DANE. THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB AN OVERVIEW ON THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD AND ON THE Brown, Tony Church, Robert Aubry Davis, Susan Eisenhower, Irwin GIELGUD AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE IN THE DRAMATIC ARTS Glusker, Marifrancis Hardison, Jeffrey Horowitz, Sherry L. Mueller, Peggy O’Brien, William W. Patton, Jean Stapleton, Patrick Stewart, and Homer Swander. It’s also a pleasure for the Guild to recognize a Founded in 1987 by John F. Andrews, THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD is a Homer Swander global nonprofit corporation that endeavors to cultivate stronger number of others who have generously supported its efforts, both on audiences for the poet we’ve long revered as history’s most reliable this happy occasion and on many memorable occasions in the past. guide to the mileposts of life. In 1994, as a way of preserving the “character” (Sonnet 85) of our era’s most enduring exemplar of David Arnold Sarah L. Morrison Page Ashley Barbara Morton the classical tradition in the rendering of Shakespeare and other Nancy Dale Becker Sherry L. Mueller dramatists, the Guild unveiled THE GOLDEN QUILL, an elegant John Elayne Bernstein Mary Lee Muromcew Safer trophy to be bestowed each year upon the artist an eminent Michael Bishop Elaine Mead Murphy selection panel – cultural leader Kitty Carlisle Hart, playwright Virginia Brody Bill and Louisa Newlin Ken Ludwig, SHAKESPEARE BIRTHPLACE TRUST director Roger Pringle, Mary Brogan Nancy M. -

033695 ISBY Insert.Indd

Francisco Shakespeare Festival, Sacramento Theatre SCOTT DENISON (Managing Director) has been a ABOUT CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY Company, New Conservatory Theatre Center, as well as leader in the arts for 40 years for Walnut Creek and others. Michael earned a BFA in technical theatre from the surrounding communities. For the last 24 years he Center REP is the resident, professional theatre company CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY Illinois Wesleyan University, and he earned a MFA in has been the General Manager of the Lesher Center of the Lesher Center for the Arts. Our season consists Lighting Design from UC Davis in 2004. Michael is also and oversees over 850 public events each year. He of six productions a year – a variety of musicals, dramas Michael Butler, Artistic Director Scott Denison, Managing Director a proud member of United Scenic Artists, Local 829, the coordinates performing arts activities with over 85 and comedies, both classic and contemporary, that union of professional designers. producers and producing organizations. He is also continually strive to reach new levels of artistic excellence the Managing Director of Center REPertory Company and professional standards. presents SOME MORE SOUND (Sound Designer) Co-designers producing 6 professional productions each season; and Keir Moorhead, Yuri Sumnicht, and Brendan West make up is the director and co-founder of Fantasy Forum Actors Our mission is to celebrate the power of the human Some More Sound, and have been providing their sound Ensemble, an adult family performing arts company imagination by producing emotionally engaging, design services to youth and regional theatre groups as which presents programs for the young and Young at intellectually involving, and visually astonishing live well as high school and college theater departments in the Heart. -

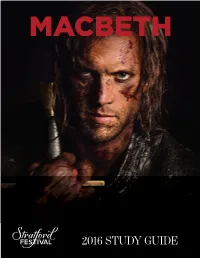

2016 Study Guide 2016 Study Guide

2016 STUDY GUIDE 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER MACBETH BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE DIRECTOR ANTONI CIMOLINO TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by Jane Petersen Burfield & Family, by Barbara & John Schubert, by the Tremain Family, and by Chip & Barbara Vallis INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: Ian Lake. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 6 Sources, Origins and Production History .................................................................... 7 The Historical Macbeth ............................................................................................ -

The Globe Players in Balboa Park by Darlene Gould Davies

The Globe Players in Balboa Park By Darlene Gould Davies I acted in the first play at the Old Globe as a permanent theater in 1937 (after the closing of the Exposition of 1935-36). I was an actor in 1937-38, but I was also a stage manager, helped with sets and props—I lived at the theatre! Then when the Globe’s director was called up by the Navy, I was chosen to be producing director—a job which I did, basically, for the next 65 years…(though my title changed). Craig Noel in 20051 Seventy-five years have passed since the 1935 California Pacific International Exposi- tion in Balboa Park and the first appearance of the Globe Players in the newly built Old Globe Theatre.2 The Globe Players moved to San Diego from Chicago where they had performed edited versions of Shakespeare’s plays in an Elizabethan-themed “Merrie England” exhibit at the 1933-34 “Century of Progress Exposition” in Chicago. Word of their popularity reached San Diegans who were busily planning an exposition to open the next year. According to theatre critic Welton Jones, “the operators of the 1935 California Pacific International Exposition in San Diego lured them to Balboa Park The Globe Players performed edited versions of 3 Shakespeare’s plays at the 1935 California Pacific hoping to duplicate their success.” International Exposition in Balboa Park. This Abbreviated Shakespeare productions postcard, signed by Rhys Williams, was collected as fit nicely with a great array of attractions in a souvenir. Courtesy of Michael Kelly. Balboa Park. -

Spring Gala 2013 a Celebration of Your Favorites Monday, March11

FRONT COVER SPRING GALA 2 013 A CELEBRATION OF YOUR FAVORITES MONDAY, MARCH11 INSIDE FRONT COVER TEXT-page 1 GALA CHAIRS DIANE & TOM TUFT BILL BORRELLE & JOHN HEARN VICE CHAIRS THE ALEC BALDWIN FOUNDATION MICHAEL T. COHEN Colliers International NY LLC SUSANNE & DOUGLAS DURST MYRNA AND FREDDIE GERSHON JODI & DAN GLUCKSMAN MARY CIRILLO-GOLDBERG & JAY N. GOLDBERG PRESENT SYLVIA GOLDEN SPRING STEPHANIE & RON KRAMER GALA GILDA & JOHN P. McGARRY, JR. 2 013 LISA AND GREGG RECHLER A CELEBRATION MARY AND DAVID SOLOMON/ GOLDMAN SACHS GIVES OF YOUR JOHANNES WORSOE Chief Administrative Officer for the Americas, FAVORITES The Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ, LTD MONDAY, AUCTION CHAIRS MARCH11 LINDA L. D’ONOFRIO SYLVIA GOLDEN JOURNAL CHAIRS CHRISTOPHER FORMANT NED GINTY ARTISTIC DIRECTOR TODD HAIMES , iabdny.com DIRECTOR MUSICAL DIRECTOR ESIGN D Lonny Price Paul Gemignani ROWN SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN A. B Anna Louizos Carmen Marc Valvo Ken Billington Acme Sound Partners RIS EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Sydney Beers Roundabout thanks all of the artists and technicians who have generously donated their time to tonight’s event and helped make this evening possible. We wish to express our gratitude to the Performer’s Unions: Actors’ Equity Association, American Federation of Television & Radio Artists, American Guild of Musical Artists, American Guild of Variety Artists, and Screen Actors’ Guild through Theatre Authority, Inc. for their cooperation in permitting the artists to appear. Spring Gala Invitation and Journal Design by I Gala proceeds benefit Roundabout Theatre Company’s Musical Theatre Fund and Education programs. Dr. Leslie Taubman and Pilar and Mike de Graffenried THANK YOU Dr. -

01 All My Sons Pp. I

01 A View from the Bridge pp. i- 9/2/10 15:37 Page i ARTHUR MILLER A View from the Bridge with commentary and notes by STEPHEN MARINO Series Editor: Enoch Brater METHUEN DRAMA 01 A View from the Bridge pp. i- 9/2/10 15:37 Page ii Methuen Drama Student Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This edition first published in the United Kingdom in 2010 by Methuen Drama A & C Black Publishers Ltd 36 Soho Square London W1D 3QY www.methuendrama.com Copyright © 1955, 1957 by Arthur Miller Subsequently © 2007 The Arthur Miller 2004 Literary and Dramatic Property Trust Commentary and notes copyright © 2010 by Methuen Drama The right of the author to be identified as the author of these works has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 ‘Chronology of Arthur Miller by Enoch Brater, with grateful thanks to the Arthur Miller Society for permission to draw on their ‘Brief Chronology of Arthur Miller’s Life and Works’. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 408 10840 6 Commentary and notes typeset by SX Composing DTP, Rayleigh, Essex Playtext typeset by Country Setting, Kingsdown, Kent Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Cox & Wyman Ltd, Reading, Berkshire CAUTION Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that these plays are subject to a royalty. They are fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations.