27 February 2020 State Development, Natural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BHP Economic Contribution Report 2017 1 Chief Financial Officer’S Introduction

Economic Contribution Report 2017 We have a long-standing commitment to transparency. We are proud of the value we generate and how this contributes to building trust with the communities in which we operate. In this Report Chief Financial Officer’s Introduction 2 Tax and our 2017 Financial Statements 20 FY2017 Total economic contribution 3 Basis of Report preparation 21 Our contribution throughout the value chain 6 Glossary 22 Approach to transparency and tax 9 Independent auditor’s report to the Directors Our payments to governments 14 of BHP Billiton Plc and BHP Billiton Limited 23 Corporate Directory 24 BHP Billiton Limited. ABN 49 004 028 077. Registered in Australia. Registered office: 171 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia. BHP Billiton Plc. Registration number 3196209. Registered in England and Wales. Registered office: Nova South, 160 Victoria Street London SW1E 5LB United Kingdom. Each of BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc is a member of the Group, which has its headquarters in Australia. BHP is a Dual Listed Company structure comprising BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc. The two entities continue to exist as separate companies but operate as a combined Group known as BHP. The headquarters of BHP Billiton Limited and the global headquarters of the combined Group are located in Melbourne, Australia. The headquarters of BHP Billiton Plc are located in London, United Kingdom. Both companies have identical Boards of Directors and are run by a unified management team. Throughout this publication, the Boards are referred to collectively as the Board. Shareholders in each company have equivalent economic and voting rights in the Group as a whole. -

Empirical Inference of Related Trading Between Two Securities: Detecting Pairs Trading, Merger Arbitrage, and Strategy Rules*

Empirical inference of related trading between two securities: Detecting pairs trading, merger arbitrage, and strategy rules* Keith Godfrey The University of Western Australia Working paper: 5 September 2013 The traditional approach to studying pairs trading is to simulate profitability using ex-post historical prices. I study the actual trades reported anonymously in security pairs and build statistical inferences of related trading. The approach is based on the time differences between trades. It can distinguish intrinsically related securities from pseudo-random sets, find stocks involved in merger arbitrage in massive sets of paired index constituents, and infer dominant trading rules of mean reversion algorithms. Empirical inference of related trading can enable further studies into pairs trading, strategy rules, merger arbitrage, and insider trading. Keywords: Inferred trading, empirical inference, pairs trading, merger arbitrage. JEL Classification Codes: G00, G10, C10, C40, C60 The availability of intraday trading or “tick” data with time resolution of a millisecond or finer is opening many avenues of research into financial markets. Analysis of two or more streams of tick data concurrently is becoming increasingly important in the study of multiple-security trading including index tracking, pairs trading, merger arbitrage, and market-neutral strategies. One of the greatest challenges in empirical trading research is the anonymity of reported trades. Securities exchanges report the dates, times, prices, and volumes traded, without identifying the traders. In studies of a single security, this introduces uncertainty of whether each market order that caused a trade was the buy or sell order, and there are documented approaches of inference such as Lee and Ready (1991). -

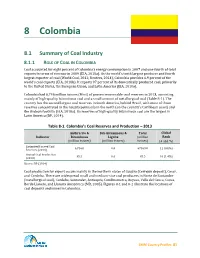

Chapter 8: Colombia

8 Colombia 8.1 Summary of Coal Industry 8.1.1 ROLE OF COAL IN COLOMBIA Coal accounted for eight percent of Colombia’s energy consumption in 2007 and one-fourth of total exports in terms of revenue in 2009 (EIA, 2010a). As the world’s tenth largest producer and fourth largest exporter of coal (World Coal, 2012; Reuters, 2014), Colombia provides 6.9 percent of the world’s coal exports (EIA, 2010b). It exports 97 percent of its domestically produced coal, primarily to the United States, the European Union, and Latin America (EIA, 2010a). Colombia had 6,746 million tonnes (Mmt) of proven recoverable coal reserves in 2013, consisting mainly of high-quality bituminous coal and a small amount of metallurgical coal (Table 8-1). The country has the second largest coal reserves in South America, behind Brazil, with most of those reserves concentrated in the Guajira peninsula in the north (on the country’s Caribbean coast) and the Andean foothills (EIA, 2010a). Its reserves of high-quality bituminous coal are the largest in Latin America (BP, 2014). Table 8-1. Colombia’s Coal Reserves and Production – 2013 Anthracite & Sub-bituminous & Total Global Indicator Bituminous Lignite (million Rank (million tonnes) (million tonnes) tonnes) (# and %) Estimated Proved Coal 6,746.0 0.0 67469.0 11 (0.8%) Reserves (2013) Annual Coal Production 85.5 0.0 85.5 10 (1.4%) (2013) Source: BP (2014) Coal production for export occurs mainly in the northern states of Guajira (Cerrejón deposit), Cesar, and Cordoba. There are widespread small and medium-size coal producers in Norte de Santander (metallurgical coal), Cordoba, Santander, Antioquia, Cundinamarca, Boyaca, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Borde Llanero, and Llanura Amazónica (MB, 2005). -

Annual Review and Summary Financial Statements 2010 Shareholder Information Continued

Centrica plc Registered office: Millstream, Maidenhead Road, Windsor, Berkshire SL4 5GD Company registered in England and Wales No. 3033654 www.centrica.com Annual Review and Summary Financial Statements 2010 Shareholder Information continued SHAREHOLDER SERVICES Centrica shareholder helpline To register for this service, please call the shareholder helpline on 0871 384 2985* to request Centrica’s shareholder register is maintained by Equiniti, a direct dividend payment form or download it from which is responsible for making dividend payments and www.centrica.com/shareholders. 01 10 updating the register. OVERVIEW SUMMARY OF OUR BUSINESS The Centrica FlexiShare service PERFORMANCE If you have any query relating to your Centrica shareholding, 01 Chairman’s Statement please contact our Registrar, Equiniti: FlexiShare is a ‘corporate nominee’, sponsored by Centrica and administered by Equiniti Financial Services Limited. It is 02 Our Performance 10 Operating Review Telephone: 0871 384 2985* a convenient way to manage your Centrica shares without 04 Chief Executive’s Review 22 Corporate Responsibility Review Textphone: 0871 384 2255* the need for a share certificate. Your share account details Write to: Equiniti, Aspect House, Spencer Road, Lancing, will be held on a separate register and you will receive an West Sussex BN99 6DA, United Kingdom annual confirmation statement. Email: [email protected] By transferring your shares into FlexiShare you will benefit from: A range of frequently asked shareholder questions is also available at www.centrica.com/shareholders. • low-cost share-dealing facilities provided by a panel of independent share dealing providers; Direct dividend payments • quicker settlement periods; Make your life easier by having your dividends paid directly into your designated bank or building society account on • no share certificates to lose; and the dividend payment date. -

Jacobs MCM- Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Of

Radi oacti ve Waste S tor age and Dispos al F acilities in S out h A ustr alia – Quantit ati ve C ost A nal ysis and Business C as e Radioactive Waste Storage and Disposal Facilities in South Australia – Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Radioactive Waste Storage and Disposal Facilities in South Australia – Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Project no: IW104700 Document title: Radioactive Waste Storage and Disposal Facilities in South Australia – Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Revision: Draft Report V1 Date: 09 February 2016 Client name: South Australian Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission Client no: Jacobs Report (0.4) Project manager: Tim Johnson Authors: Darron Cook, Charles McCombie, Neil Chapman, Nigel Sullivan, Rohan Zauner, Tim Johnson File name: J:\IE\Projects\03_Southern\IW104700\21 Deliverables\Reformatted Docs for Client Release\09022016 Combined Papers V1.0.docx Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited ABN 37 001 024 095 Floor 11, 452 Flinders Street Melbourne VIC 3000 PO Box 312, Flinders Lane Melbourne VIC 8009 Australia T +61 3 8668 3000 F +61 3 8668 3001 www.jacobs.com COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Document history and status Revision Date Description By Review Approved V0 19 Jan 2016 For Client review Darron Darron Cook Darron Cook, team Cook V1 9 February For public consultation Tim Johnson Darron Cook Darron Cook IW104700 i Radioactive Waste Storage and Disposal Facilities in South Australia – Quantitative Cost Analysis and Business Case Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. -

BHP Billiton Iron Ore Management Approach

BHP Billiton Iron Ore Orebody 32 East AWT – Environmental Referral Document BHP Billiton Iron Ore management approach 1.1 Environmental management overview BHP Billiton has developed a Company Charter and Sustainable Development Policy for its operations. The Company Charter and Sustainable Development Policy (BHP Billiton Iron Ore, 2013a) are guiding resources for maintaining an emphasis on health, safety, environment and community and clarifying a broader commitment to aspects of sustainability including biodiversity, human rights, ethical business practices and economic contributions at all BHP Billiton sites. To interpret and support the Company Charter and BHP Billiton Iron Ore’s Sustainable Development Policy, BHP Billiton Iron Ore has developed an Environmental Governance Hierarchy, an Environmental Management System and is currently developing a series of Regional Management Strategies. 1.2 Environment Governance Hierarchy BHP Billiton Iron Ore now operates under an Environmental Governance Hierarchy (Figure 1). The Environment Governance Hierarchy provides the processes and practices that enable BHP Billiton Iron Ore to achieve its environmental objectives, reduce its environmental impacts and increase its operating efficiency. It enables environmental legal compliance to be undertaken and audited and provides for continual improvement in environmental performance. Figure 1: BHP Billiton Iron Ore Environmental Governance Hierarchy As shown in Figure 1, BHP Billiton Iron Ore’s environment governance hierarchy is broadly comprised of three tiers, representative of BHP Billiton Iron Ore’s different levels of management – BHP Billiton (corporate level), BHP Billiton Iron Ore (Business Unit level) and site specific (operations level) – and reflective of BHP Billiton’s top-down approach to environmental management across the Group. -

Rio Tinto BHP, Tesco, Sainsbury, Arcelormittal, National Grid

Quarterly Engagement Rio Tinto Report July-September BHP, Tesco, 2020 Sainsbury, ArcelorMittal, National Grid 2 LAPFF QUARTERLY ENGAGEMENT REPORT | JULY-SEPTEMBER 2020 lapfforum.org CLIMATE EMERGENCY Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura Aboriginal Corporation Rio Tinto under pressure from investors over Juukan Gorge As LAPFF has been learning more about “My interaction with Mr. Rio Tinto’s involvement in the destruc- Thompson, in his roles as Chair tion of the historically significant caves of both Rio Tinto and 3i, has been at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia, there have been increasing concerns positive thus far. However, I sense about the company’s corporate govern- that investors are losing confidence ance practices. Consequently, the Forum in his leadership and in his board at – along with other investor groups, most Rio Tinto. It will be a long road back What happened at prominently the Australasian Centre for for the company.” Juukan Gorge? Corporate Responsibility (ACCR) - has been pushing the company to review its Cllr Doug McMurdo In May, Rio Tinto destroyed 46,000-year- corporate governance arrangements. old Aboriginal caves in the Juukan One of the main strategies in this Gorge region of Western Australia. The engagement has been to issue press responding to information issued by explosions were part of a government releases citing LAPFF’s concerns as vari- Australian Parliamentary inquiries into sanctioned mining exploration in ous details of Rio Tinto’s practices were this matter. There appears to be increas- the region. The caves are of cultural revealed through a range of investiga- ing evidence of corporate governance fail- significance to the Puutu Kunti tions. -

BP Transforms Its US Onshore Oil and Gas Business, Acquiring World-Class Unconventional Assets from BHP 26 July 2018

BP transforms its US onshore oil and gas business, acquiring world-class unconventional assets from BHP 26 July 2018 Acquisition accretive to earnings and cash flow, delivered within existing financial frame Company increases dividend for first time in 15 quarters Upgrades and repositions BP’s US onshore business Brings advantaged oil and gas assets in world-class basins Adds 190,000 boe/d production and 4.6 billion boe discovered resources Boosts liquids share of BP’s US onshore production and resources Offers growth into the next decade Creates significant value Accretive to earnings and cash flow on a per share basis Increases Upstream free cash flow target by $1 billion to $14-15 billion in 2021 Generates estimated pre-tax synergies of over $350 million a year Fully accommodated within existing financial frame Total cash consideration of $10.5 billion – 50% on completion, 50% deferred over six months Up to $5-6 billion of additional divestments planned to fund share buybacks of up to $5-6 billion over time Unchanged financial frame of $15-17 billion annual organic capital expenditure to 2021, and gearing of 20-30% BP transforms its US onshore oil and gas business, acquiring world-class unconventional assets from BHP Page | 1 Strong free cashflow outlook supports dividend rise for second quarter 2018 2.5% rise to 10.25c per ordinary share is first dividend increase since third quarter 2014 In a move that will upgrade and materially reposition its US onshore oil and gas business, BP has agreed to acquire a portfolio of world-class unconventional oil and gas assets from BHP. -

How Do Extractive Companies Measure and Report Their Social Performance? Review of Approaches to Impact Assessment

ECONOMIC AND PRIVATE SECTOR PROFESSIONAL EVIDENCE AND APPLIED KNOWLEDGE SERVICES HELPDESK REQUEST How do extractive companies measure and report their social performance? Review of approaches to impact assessment Carolin Williams ODI April 2014 How do extractive companies measure and report their social performance? EPS-PEAKS is a consortium of organisations that provides Economics and Private Sector Professional Evidence and Applied Knowledge Services to the DfID. The core services include: 1) Helpdesk 2) Document library 3) Information on training and e-learning opportunities 4) Topic guides 5) Structured professional development sessions 6) E-Bulletin To find out more or access EPS-PEAKS services or feedback on this or other output, visit the EPS- PEAKS community on http://partnerplatform.org/eps-peaks or contact Yurendra Basnett, Knowledge Manager, EPS-PEAKS core services at [email protected]. Disclaimer Statement: The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Consortium partner organisations, DFID or the UK Government. The authors take full responsibility for any errors or omissions contained in this report. 2 How do extractive companies measure and report their social performance? Table of Contents 1 Query and approach 4 2 Individual company level reviews of social performance reporting 6 2.1 Anglo American 6 2.2 BG Group 11 2.3 BHP Billiton 13 2.4 BP 17 2.5 Newmont 19 2.6 Rio Tinto 21 2.7 Royal Dutch Shell 24 2.8 Tullow Oil 27 3 Headlines from reviews of companies’ social performance reporting 30 3 How do extractive companies measure and report their social performance? 1 Query and approach Extractive companies tend to spend significant amounts on community based development projects to improve their social performance. -

BHP OPERATIONAL REVIEW for the NINE MONTHS ENDED 31 MARCH 2021 Note: All Guidance Is Subject to Further Potential Impacts from COVID-19 During the 2021 Financial Year

Release Time IMMEDIATE Date 21 April 2021 Release Number 05/21 BHP OPERATIONAL REVIEW FOR THE NINE MONTHS ENDED 31 MARCH 2021 Note: All guidance is subject to further potential impacts from COVID-19 during the 2021 financial year. Record production was achieved at Western Australia Iron Ore (WAIO) and record average concentrator throughput was delivered at Escondida. Production guidance for the 2021 financial year remains unchanged for petroleum and iron ore. Copper guidance has increased to between 1,535 kt and 1,660 kt and reflects stronger than expected performance at Escondida. Metallurgical coal guidance has been reduced to between 39 and 41 Mt as a result of significant wet weather impacts during the December 2020 and March 2021 quarters. Energy coal guidance has been reduced to between 18 and 20 Mt as a result of significant weather impacts at New South Wales Energy Coal (NSWEC) and lower than expected volumes at Cerrejón. Full year unit cost guidance(1) (based on exchange rates of AUD/USD 0.70 and USD/CLP 769) remains unchanged for Petroleum and WAIO. Unit costs for Escondida have been lowered to be between US$0.95 and US$1.10(1) per pound, reflecting strong production and lower deferred stripping costs. Unit costs for Queensland Coal have been increased to be between US$74 and US$78(1) per tonne, reflecting lower expected volumes for the full year. The Bass Strait West Barracouta gas project achieved first production in April 2021, and is on schedule and budget. Our major projects under development are also progressing to plan. -

Centrica Annual Report 2012

Centrica plc plc Centrica Annual Report and Accounts 2012 INTEGRATED ENERGY CENTRicA PLC Registered office: Millstream, Maidenhead Road, Windsor, Berkshire SL4 5GD Company registered in England Annual Report and Accounts 2012 and Wales No. 3033654 centrica.com Centrica plc Annual Report and Accounts 2012 Centrica plc Annual Report and Accounts 2012 INTEGRATED ENERGY IS WHAT WE DO. It means constantly exploring new ways to source, procure and generate an affordable supply of energy. It means integrating innovation and technology into the home, giving our customers access to energy and services, whenever they need it. It means working with governments, regulators and partners to make the right things happen at the right time. Most important of all, it means empowering our customers to take control of their energy needs as we work towards a low carbon future. INTEGRATED ENERGY FROM CENTRicA. This report is printed on Revive 100 Silk which is made from 100% recycled post- consumer fibre that is Totally Chlorine Free. This paper has been independently certified according to the rules of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC®). ONLINE Designed and produced by INTEGRATED ENERGY Photography by David Hares, Mike What it means to us How we achieve it Abrahams, Igor Emmerich, Charlie Fawell Disclaimer and David Partner. This Annual Report and Accounts does not constitute an invitation to underwrite, subscribe for, or otherwise acquire or dispose of any Centrica shares or other securities. Printed by CPI Colour Limited Use your smartphone or tablet This Annual Report and Accounts contains certain forward-looking statements with respect to the financial ISO14001, FSC certified and CarbonNeutral®. -

Petroleum CSG Briefing, 24 May 2010 Slide 2 Agenda

Petroleum Briefing J. Michael Yeager Group and Chief Executive – BHP Billiton Petroleum Monday 24 May 2010 Disclaimer Reliance on Third Party Information The views expressed here contain information that has been derived from publicly available sources that have not been independently verified. No representation or warranty is made as to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information. This presentation should not be relied upon as a recommendation or forecast by BHP Billiton. Forward Looking Statements This presentation includes forward-looking statements within the meaning of the U.S. Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 regarding future events and the future financial performance of BHP Billiton. These forward-looking statements are not guarantees or predictions of future performance, and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond our control, and which may cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed in the statements contained in this presentation. For more detail on those risks, you should refer to the sections of our annual report on Form 20-F for the year ended 30 June 2009 entitled “Risk factors”, “Forward looking statements” and “Operating and financial review and prospects” filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. No Offer of Securities Nothing in this release should be construed as either an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell BHP Billiton securities in any jurisdiction. Non-GAAP Financial Information BHP Billiton results are reported under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). References to Underlying EBIT and EBITDA exclude any exceptional items.