Denuclearization of Central Asia Jozef Goldblat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elections and Identity Politics in Kyrgyzstan 1989-2009 - Moving Beyond the ‘Clan Politics’ Hypothesis

LSE ELECTIONS AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN KYRGYZSTAN 1989-2009 - MOVING BEYOND THE ‘CLAN POLITICS’ HYPOTHESIS Fredrik M Sjoberg Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) Department of Government London School of Economics and Political Science London July 2009 Final version: 01/12/2009 11:49 UMI Number: U615307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615307 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. Fredrik M Sjoberg 2 Abstract This dissertation examines the emergence of political pluralism in the unlikely case of Kyrgyzstan. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

With a Focus on Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan

A Strategic Conflict Analysis of Central Asia With a Focus on Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan Niklas L.P. SwanstrSwanströmöm Svante E. Cornell Anara Tabyshalieva June 2005 A Conflict and Security Analysis of Central Asia with a Focus on Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan Niklas L.P. Swanström Svante E. Cornell Anara Tabyshalieva Prepared for the Swedish Development Cooperation Agency June 1, 2005 A Strategic Conflict Analysis of Central Asia 1 Strategic Conflict Analysis of Central Asia with a Focus on Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan .... 1 1. General Security and Conflict Situation in Central Asia................................................... 1 1.1. General conflict development........................................................................................................2 1.1.1. Multilateral security arrangements..................................................................................................3 1.1.2. Conflict management, resolution and conflict prevention...................................................................4 1.1.3. Major changes 2002-2005, summarily..........................................................................................5 1.2. Conflict lines in Central Asia..........................................................................................................5 1.2.1 Ethnicity and Border Issues............................................................................................................6 1.2.2 Regionalism....................................................................................................................................7 -

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

An Overview on the Subterranean Fauna from Central Asia

Ecologica Montenegrina 20: 168-193 (2019) This journal is available online at: www.biotaxa.org/em An overview on the subterranean fauna from Central Asia VASILE DECU1†, CHRISTIAN JUBERTHIE2*, SANDA IEPURE1,3, 4, VICTOR GHEORGHIU1 & GEORGE NAZAREANU5 1 Institut de Spéologie Emil Racovitza, Calea 13 September, 13, R0 13050711 Bucuresti, Rumania 2 Encyclopédie Biospéologique, Edition. 1 Impasse Saint-Jacques, 09190 Saint-Lizier, France 3Cavanilles Institute of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology, University of Valencia, José Beltrán 15 Martínez, 2, 46980 Paterna, Valencia, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 4University of Gdańsk, Faculty of Biology, Department of Genetics and Biosystematics, Wita Stwoswa 59, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland 5Muzeul national de Istorie naturala « Grigore Antipa » Sos, Kiseleff 1, Bucharest, Rumania E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Received 9 December 2018 │ Accepted by V. Pešić: 8 March 2019 │ Published online 21 March 2019. Abstract Survey of the aquatic subterranean fauna from caves, springs, interstitial habitat, wells in deserts, artificial tunnels (Khanas) of five countries of the former URSS (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tadjikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan) located far east the Caspian Sea. The cave fauna present some originalities: - the rich fauna of foraminiferida in the wells of the Kara-Kum desert (Turkmenistan); - the cave fish Paracobitis starostini from the Provull gypsum Cave (Turkmenistan); - the presence of a rich stygobitic fauna in the wells of the Kyzyl-Kum desert (Uzbekistan); - the rich stygobitic fauna from the hyporheic of streams and wells around the tectonic Issyk-Kul Lake (Kyrgyzstan); - the eastern limit of the European genus Niphargus from the sub-lacustrin springs on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea (Kazakhstan); - the presence of cave fauna of marine origin. -

Acta Slavica Iaponica No 16

Preface The Slavic Research Center (SRC) of Hokkaido University held an international symposium entitled “Eager Eyes Fixed on Slavic Eurasia: Change and Progress” in Sapporo, Japan, on July 6 and 7 of 2006. The symposium was mainly funded by a special scientific research grant from the Japanese Ministry of Education’s Twenty-first Century Center of Excellence Program (“Making a Discipline of Slavic Eurasian Studies: 2003–2008,” project leader, Ieda Osamu) and partly assisted by Grants-in- Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (“An Emerging New Eurasian Order: Russia, China and Its Interactions toward its Neighbors: 2006–2009,” project leader, Iwashita Akihiro). The symposium started with an opening speech, Martha Brill Olcott’s “Eyes on Central Asia: How To Understand the Winners and Losers.” The aim of the symposium was to redefine the former Soviet space in international relations, paying closest attention to the “surrounding regions” of Eurasia. Well-known specialists on the region came together in Sapporo to debate topics such as “Russian Foreign Policy Reconsidered,” “South Asia and Eurasia,” “Central Asia and Eurasian Cooperation,” “Challenges of the Sino-Russian Border,” and “Russia in East Asia.” All of the sessions noted China’s presence in the region. Central Asian issues and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization were mentioned in the sessions on South Asia and East Asia. Every participant recognized the crucial importance of increasing interactions in and around Eurasia. Eighteen papers were submitted to the symposium: four from Japan, three from China, two each from Russia and the United States, and one each from Korea, Hungary, India, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, and Australia. -

6. Current Status of the Environment

6. Current Status of the Environment 6.1. Natural Environment 6.1.1. Desertification Kazakhstan has more deserts within its territory than any other Central Asian country, and approximately 66% of the national land is vulnerable to desertification in various degrees. Desertification is expanding under the influence of natural and artificial factors, and some people, called “environmental refugees,” are obliged to leave their settlements due to worsened living environments. In addition, the Government of RK (Republic of Kazakhstan) issued an alarm in the “Environmental Security Concept of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2004-2015” that the crisis of desertification is not only confined to Kazakhstan but could raise problems such as border-crossing emigration caused by the rise of sandstorms as well as the transfer of pollutants to distant locations driven by large air masses. (1) Major factors for desertification Desertification is taking place due to the artificial factors listed below as well as climate, topographic and other natural factors. • Accumulated industrial wastes after extraction of mineral resources and construction of roads, pipelines and other structures • Intensive grazing of livestock (overgrazing) • Lack of farming technology • Regulated runoff to rivers • Destruction of forests 1) Extraction of mineral resources Wastes accumulated after extraction of mineral resources have serious effects on the land. Exploration for oil and natural gas requires vast areas of land reaching as much as 17 million hectares for construction of transportation systems, approximately 10 million hectares of which is reportedly suffering ecosystem degradation. 2) Overgrazing Overgrazing is the abuse of pastures by increasing numbers of livestock. In the grazing lands in mountainous areas for example, the area allocated to each sheep for grazing is 0.5 hectares, compared to the typical grazing space of 2 to 4 hectares per sheep. -

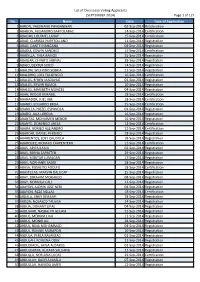

List of Oversease Voting Applicants (SEPTEMBER 2014) Page 1 of 127 No

List of Oversease Voting Applicants (SEPTEMBER 2014) Page 1 of 127 No. Name Date Type of Application 1 AARON, VALERIANO PANGANIBAN 02-Sep-2014 Reactivation 2 ABABON, ALEJANDRO BARTOLABAC 14-Sep-2014 Certification 3 ABACAN, LOUIMEL LABAY 15-Sep-2014 Certification 4 ABAD, CLARISSA PUERTOLLANO 11-Sep-2014 Registration 5 ABAD, DANTE MANGANA 04-Sep-2014 Registration 6 ABADIA, EDWIN SANCHEZ 15-Sep-2014 Certification 7 ABADILLA, THEA RAMOS 25-Sep-2014 Registration 8 ABAIGAR, CHINITO JABINAL 28-Sep-2014 Registration 9 ABAJO, DEXTER SUICO 14-Sep-2014 Registration 10 ABALON, WILFRIDO SOBRIA 11-Sep-2014 Registration 11 ABALORIO, JOEL FULGENCIO 16-Sep-2014 Certification 12 ABALOS, EFREN MADAYAG 01-Sep-2014 Registration 13 ABALOS, ERWIN RAMOS 10-Sep-2014 Registration 14 ABALOS, MARIBETH MONCES 04-Sep-2014 Registration 15 ABAN, REGGIE MIRABEL 18-Sep-2014 Certification 16 ABANADOR, JUEL ABE 18-Sep-2014 Certification 17 ABANID, EDUARDO BROA 25-Sep-2014 Certification 18 ABANILLA, HIEZEL ESPANOLA 01-Sep-2014 Registration 19 ABAÑO, AILA LORENA 16-Sep-2014 Registration 20 ABANTAS, MOHAIMEN MENOR 16-Sep-2014 Registration 21 ABANTE, DOMINGO ABELA 14-Sep-2014 Certification 22 ABARA, ROMEO ALEJANDRO 22-Sep-2014 Certification 23 ABARCAR, DANIEL PERDIDO 18-Sep-2014 Registration 24 ABARIENTOS, JOEY CAUDILLA 18-Sep-2014 Registration 25 ABARQUEZ, RICHARD CARPENTERO 12-Sep-2014 Certification 26 ABAS, APIPA KAMIL 02-Sep-2014 Registration 27 ABAS, BERNA SAPBETEN 29-Sep-2014 Registration 28 ABAS, MOKTAR LUMAGAN 17-Sep-2014 Registration 29 ABAS, NORHANIE SADDI 28-Sep-2014 -

42399-023: CAREC Transport Corridor I (Bishkek-Torugart Road

Completion Report Project Number: 42399-023 Loan Number: 2755 Loan Number: 3204 Grant Number: 0418 March 2019 Kyrgyz Republic: CAREC Corridor 1 (Bishkek– Torugart Road) Project 3 This document is being disclosed to the public in accordance with ADB's Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – som (Som) At Appraisal Additional Financing At Project Completion (25 April 2011) (30 October 2014) (31 December 2017) Som1.00 = $0.0213 $0.0177 $0.0145 $1.00 = Som46.916 Som56.508 Som69.140 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CAREC – Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation CPS – country partnership strategy EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMP – environment management plan ICB – international competitive bidding ICS – individual consultant selection IPIG – Investment Projects Implementation Group IRI – international roughness index KJSNR – Karatal-Japaryk State Nature Reserve LARP – land acquisition and resettlement plan MOTR – Ministry of Transport and Roads NLA – normative legal act PBM – performance-based maintenance PCR – project completion review PRC – People’s Republic of China SDR – special drawing right TOR – terms of reference VOC – vehicle operating cost NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic and its agencies ends on 31 December. “FY” before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2017 ends on 31 December 2017. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars. Vice-President S. Chen, Operations 1 Director General W. E. Liepach, Central and West Asia Regional Department (CWRD) Director C. McDeigan, Kyrgyz Resident Mission, CWRD Sector Director D. S. Pyo, Transport and Communications Division, CWRD Team leader M. -

Molecular Characterization of Leishmania RNA Virus 2 in Leishmania Major from Uzbekistan

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Molecular Characterization of Leishmania RNA virus 2 in Leishmania major from Uzbekistan 1, 2,3, 1,4 2 Yuliya Kleschenko y, Danyil Grybchuk y, Nadezhda S. Matveeva , Diego H. Macedo , Evgeny N. Ponirovsky 1, Alexander N. Lukashev 1 and Vyacheslav Yurchenko 1,2,* 1 Martsinovsky Institute of Medical Parasitology, Tropical and Vector Borne Diseases, Sechenov University, 119435 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (Y.K.); [email protected] (N.S.M.); [email protected] (E.N.P.); [email protected] (A.N.L.) 2 Life Sciences Research Centre, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, 71000 Ostrava, Czech Republic; [email protected] (D.G.); [email protected] (D.H.M.) 3 CEITEC—Central European Institute of Technology, Masaryk University, 62500 Brno, Czech Republic 4 Department of Molecular Biology, Faculty of Biology, Moscow State University, 119991 Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-597092326 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 19 September 2019; Accepted: 18 October 2019; Published: 21 October 2019 Abstract: Here we report sequence and phylogenetic analysis of two new isolates of Leishmania RNA virus 2 (LRV2) found in Leishmania major isolated from human patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis in south Uzbekistan. These new virus-infected flagellates were isolated in the same region of Uzbekistan and the viral sequences differed by only nineteen SNPs, all except one being silent mutations. Therefore, we concluded that they belong to a single LRV2 species. New viruses are closely related to the LRV2-Lmj-ASKH documented in Turkmenistan in 1995, which is congruent with their shared host (L. -

The Changed Position of Ethnic Russians and Uzbeks

KYRGYZ LEADERSHIP AND ETHNOPOLITICS BEFORE AND AFTER THE TULIP REVOLUTION: THE CHANGED POSITION OF ETHNIC RUSSIANS AND UZBEKS By Munara Omuralieva Submitted to Central European University Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Supervisor: Professor Matteo Fumagalli CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2008 Abstract The Soviet Union’s multi-ethnic legacy in the Central Asian region, particularly in Kyrgyzstan was a crucial factor that largely impacted its post-independence state consolidation and transition. Especially the nation-building became difficult due to the ethnic heterogeneity of its population. More recently in 2005 there was the “Tulip Revolution”, basically an overthrow of the northern president by the southern clan leader. Despite the fact that the system and character of the government and of any other governmental structures did not change following the so- called Kyrgyz “Tulip Revolution”, there have been observations of the dramatic changes for the worse in the position of ethnic minorities, more specifically Russians and Uzbeks, and their relation with the titular nation. This work uses interviews and media material in order to demonstrate how the elite change has caused the changes analyzed in the thesis. The findings of the research demonstrate that the elite change, which was a result of 2005 events, is the main factor that has caused negative shifts in the political representation, ethnic organizations becoming more active and politicized, official policies taking more nationalistic tones, and in deteriorated inter-ethnic relations. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements I want to express deep appreciation to my supervisor Professor Matteo Fumagalli for his useful comments and suggestions throughout the writing process. -

Remote Sensing

remote sensing Article Quantitative Assessment of Vertical and Horizontal Deformations Derived by 3D and 2D Decompositions of InSAR Line-of-Sight Measurements to Supplement Industry Surveillance Programs in the Tengiz Oilfield (Kazakhstan) Emil Bayramov 1,2,*, Manfred Buchroithner 3 , Martin Kada 2 and Yermukhan Zhuniskenov 1 1 School of Mining and Geosciences, Nazarbayev University, 53 Kabanbay Batyr Ave, Nur-Sultan 010000, Kazakhstan; [email protected] 2 Methods of Geoinformation Science, Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformation Science, Technical University of Berlin, 10623 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] 3 Institute of Cartography, Helmholtzstr. 10, 01069 Dresden, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This research focused on the quantitative assessment of the surface deformation veloci- ties and rates and their natural and man-made controlling factors at Tengiz Oilfield in Kazakhstan using the Small Baseline Subset remote sensing technique followed by 3D and 2D decompositions and cosine corrections to derive vertical and horizontal movements from line-of-sight (LOS) mea- Citation: Bayramov, E.; Buchroithner, surements. In the present research we applied time-series of Sentinel-1 satellite images acquired M.; Kada, M.; Zhuniskenov, Y. during 2018–2020. All ground deformation derivatives showed the continuous subsidence at the Quantitative Assessment of Vertical Tengiz oilfield with increasing velocity. 3D and 2D decompositions of LOS measurements to vertical and Horizontal Deformations movement showed that the Tengiz Oil Field 2018–2020 continuously subsided with the maximum Derived by 3D and 2D annual vertical deformation velocity around 70 mm. Based on the LOS measurements, the maximum Decompositions of InSAR annual subsiding velocity was observed to be 60 mm.