Figure 1. Jianguo Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 County of Allegheny Comprehensive Annual Financial Report

2018 COUNTY OF ALLEGHENY PENNSYLVANIA Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2018 PREPARED BY CHELSA WAGNER, CONTROLLER 2018 County of Allegheny Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Contents INTRODUCTORY SECTION Controller's Letter of Transmittal 1 GFOA Certificate of Achievement 19 Organizational Chart 21 Officials of Allegheny County 23 FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditor's Report 25 Management's Discussion and Analysis 31 Basic Financial Statements 53 Government-wide Financial Statements 55 Statement of Net Position 55 Statement of Activities 58 Governmental Fund Financial Statements 60 Balance Sheet 60 Reconciliation of the Governmental Funds - Balance Sheet to the Statement of Net Position 65 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances 66 Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances of Governmental Funds to the Statement of Activities 70 Proprietary Fund Financial Statements 71 Statement of Net Position 71 Statement of Revenues, Expenses and Changes in Net Position 72 Statement of Cash Flows 73 Fiduciary Fund Financial Statements 74 Statement of Fiduciary Net Position 74 Statement of Changes in Fiduciary Net Position 75 Component Unit Financial Statements 76 Statement of Net Position 76 Statement of Activities 82 2018 County of Allegheny Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Contents Notes to Financial Statements 85 (1) Summary of Significant Accounting Policies 85 (2) Legal Compliance 113 (3) Cash and Investments 113 (4) Property -

Fiberarts Guild of Pittsburgh, Inc. Promoting Appreciation of Fiber Art and Fostering Its Development

fiberarts guild of pittsburgh, inc. Promoting appreciation of fiber art and fostering its development. FALL 2013 www.fiberartspgh.org • [email protected] • P.O.Box 5478 • Pittsburgh PA 15206 President’s Message We’ll begin, with a spin… Today I entertained my darling daughter with the Ceremonial Staff of the Fiber Artist, lent to me as a symbol of my new role in the Guild. I danced around it, hoisted it carefully above my head and tipped it in gentle sway to the tune of “Pure Imagination” – the song from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. As I danced my spontaneous routine, I thought about my role in the Guild. I imagined myself in a purple top hat throwing open the door to a com pletely incredible wonderland. If you want to view paradise, simply take a tour of UPDATE the TechShop, attend a critique and hear a lecture by Akiki Kotani, learn the art of Chinese Knotting, irst of all, thank you to the thousands of folks who participated, have a Fiber Conversation and a studio visit with created, cared for, and loved the Knit the Bridge project. We are thrilled Amber Coppings, enjoy a presentation by Mary Fthat it was received so warmly and looked out for so well. We’re pleased Mazziotti, schmooze at the opening reception to report that the monthlong installation was vandalism free (except for a pos for The New Collective, get inspired at Donna sibly accidental cherry slushie incident) and brought many visitors downtown. Kearns’ studio, and participate in our members Both the Warhol Museum and Kayak Pittsburgh reported significant increases show, Edge to Edge. -

Picklesburgh Official 2021 Announcement of Dates

PICKLESBURGH NEWS ALERT Today, the Pittsburgh Downown Partnership (PDP) received final approval from Allegheny County Council for use of the Andy Warhol (7th St) Bridge for Picklesburgh, slated to return Friday, August 20 – Sunday, August 22, 2021. The PDP is actively working with the City to finalize the footprint, but it is expected that this highly popular event will expand from the bridge onto Ft. Duquesne Blvd to better accommodate the anticipated crowds. Twice voted the #1 Specialty Food Festival in the US, this culinary and cultural celebration will, once again, fly the signature 35’ Heinz pickle balloon on the Andy Warhol Bridge. As with prior activations, Picklesburgh will offer a unique space for festival goers to linger, enjoy food, listen to music and relish the energy of the event. A massive array of dill-ectable products and foods will be central to all that is Picklesburgh, but the event will also have a lot more for pickle fanatics to experience, from dozens of live music performances, to other popular activities like Pickle Cocktails, Pickle Beer, DIY Pickling Demos, Pickle Juice Drinking Contest, Li’l Gherkins KidsPlay area, and an abundance of pickle-themed apparel, merch, and much more. Vendors interested in participating can now apply online at: https://downtownpittsburgh.com/get-involved/vendor-opportunities/ “As a signature event for Pennsylvania and the City of Pittsburgh, Picklesburgh attracts thousands of visitors from near and far and is an exceptional way to highlight all of what Downtown has to offer as a destination” Jeremy Waldrup, president and CEO of the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership commented. -

Public Works' Andy Warhol Bridge Project Honored by March of Dimes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Amie M. Downs June 27, 2019 412-350-3711 (office) 412-327-3700 (cell) [email protected] Public Works’ Andy Warhol Bridge Project Honored by March of Dimes PITTSBURGH – The Department of Public Works’ Andy Warhol (Seventh Street) Bridge rehabilitation project, done in conjunction with PennDOT and the Federal Highway Administration, was recognized by the March of Dimes as the Transportation Project of the Year for 2019. The selection, made by a committee of industry leaders, was announced in January and was formally presented during the 9th-annual March of Dimes Transportation, Building and Construction Awards Luncheon held earlier today at the Westin Convention Center. “We are honored and humbled that our work on the Andy Warhol Bridge is being recognized by the March of Dimes,” said County Executive Rich Fitzgerald. “Getting a project of this size done required the collective efforts of so many from the federal, state, and local levels, including our team in the Department of Public Works, our contractors, and our elected officials. We’re extremely thankful for their commitment, and by working together, they’ve ensured that one of the county’s most iconic bridges will be used and enjoyed for generations to come.” Since 2011, the March of Dimes has honored individuals, organizations, and projects for achievements and efforts to promote economic development in western Pennsylvania. The $25.4 million Andy Warhol Bridge project was submitted to March of Dimes for recognition by Michael Baker International, which was contracted by Public Works to perform structural analysis and design of the bridge rehabilitation. -

AGAIN) the Big Lift Brings Big Changes to Macdonald Bridge Cover: Angus L

Fall 2016 – Issue #1005 BORN A BUILDER: President and CEO Michael Flowers is retiring after a career of engineering, constructing, and leading HISTORY IN THE MAKING (AGAIN) The Big Lift Brings Big Changes to Macdonald Bridge Cover: Angus L. Macdonald Bridge | Halifax, Nova Scotia www.AmericanBridge.net AMERICAN BRIDGE CONNECTIONS CONTENTS Fall 2016 – Issue #1005 History in the Making (Again) The Big Lift Brings Big Changes to Macdonald Bridge FEATURE - 4 Born a Builder: President and CEO Michael Flowers is retiring after a career of engineering, constructing, and leading FEATURE - 16 Kevin Smith FEATURED EMPLOYEE - 22 Frank Mydlinski and Don Ulemek IN MEMORIAM - 24 NEW EMPLOYEES - 26 EVENTS + NEWS - 26 CURRENT CONTRACTS + PROJECT WINS - 27 Waldo-Hancock Bridge, Duarte Bridge, and more FLASHBACKS - 28 Three Sisters Stand Out in the City of Bridges EXTENDED FLASHBACK - 30 History of the Hard Hat BRIDGE TO SAFETY - 32 FEATURE HISTORY IN THE MAKING (AGAIN) The Big Lift Brings Big Changes to Macdonald Bridge Photo credit: Lynn Fergusson 4 American Bridge Canada Company (ABCC) is well underway with the Angus L. Macdonald Bridge Suspended Spans Deck Replacement project in Halifax, Nova Scotia, known locally as “The Big Lift.” Continuing the tradition of challenging and unique projects, ABCC is performing a complete replacement of the bridge’s suspended spans—while keeping it operational. The only other time this type of project has been completed was nearly 15 years ago on the Lions Gate Bridge in Vancouver, British Columbia—also by ABCC. Lessons learned from ABCC’s success on the Lions Gate Bridge Project provided valuable insight and aided ABCC’s engineering and design efforts for the Angus L. -

Carson Chronicle

Carson Chronicle Interview with Mr.Sieminski Carson Middle School By:Tejas Prasanna I retired, all at N.A.S.H. 17 assistant principal for On January 18th, I of those years I was an Moniteau School District. Volume 22 Issue 2 interviewed Mr. Sieminski. assistant principal, and for Then, I became a principal He is a retired principal of the last five years I was a at Valley High School, be- Winter 2016/2017 N.A.S.H. and is filling in for principal. fore becoming an assistant Mrs. Crimone, our principal at N.A.S.H. Points of Interest CMS Assistant Q: When you principal, while were little, what Q: Do you have a favorite 2/12—President Lincoln’s she is out on ma- did you want to school? Birthday ternity leave. Here be when you A: In all my time in working 2/14—Valentine’s Day are the questions grew up? at N.A.S.H., I do have to 2/14—Celebrate Freder- A: I wanted to say N.A.S.H. even though I I asked Mr. ick Douglas’s Birthday Sieminski and the be a carpenter. like Carson too. answers he provid- 2/24—GOLD Program ed. Q: What were Q: Do you have a favorite 2/13-2/24—NASH you before you were a school besides Spring Musical Q: How long have you principal? N.A.S.H.? worked at North Alleghe- A: I was first a teacher, A: Well, then, it has to ny? and I taught Social be Carson. -

Australia's Gateway Cities Report Launch

CITY OF NEWCASTLE Lord Mayoral Minute Page 1 Subject: LMM 26/11/2019 - Australia’s Gateway Cities Report Launch MOTION That City of Newcastle: 1. Notes that on Monday, 25 November 2019, City of Newcastle joined with City of Wollongong, City of Geelong, the Committee for Geelong, and the Minister for Population, Cities and Urban Infrastructure, the Hon. Alan Tudge MP to launch the Australia’s Gateway Cities: Gateways to Growth report at Parliament House in Canberra; 2. Thanks our City of Newcastle staff for their collaborative approach to producing this report with our partners, including, City of Wollongong, the Committee for Geelong, City of Geelong, Deakin University, the University of Newcastle and the University of Wollongong; 3. Notes the significant recommendations of the report, including; a. The further development of the shared interests between City of Newcastle, City of Wollongong and City of Geelong, as Australia’s Gateway Cities; b. Infrastructure development with Federal Government support to develop more accessible and sustainable transport connections for both passengers and freight; c. Fostering Innovation and economic growth and diversification through fiscal rebalancing to unlock the latent potential of Australia’s Gateway Cities; d. Supporting strong and skilled workforces through integrated planning to identify future and emerging workforce skills, particularly for transitioning economies. 4. Commends these recommendations to the NSW Government, and the Commonwealth Government, and sends a copy of the report the Prime Minister, the Hon. Scott Morrison MP, Premier of NSW, the Hon. Gladys Berejiklian MP, Deputy Premier and Minister for Regional NSW, Industry and Trade, the Hon. John Barilaro MP, and Minister for Planning and Public Spaces, the Hon. -

Allegheny County Council Regular Meeting

ALLEGHENY COUNTY COUNCIL REGULAR MEETING - - - BEFORE: John P. DeFazio - President, Council-At-Large Nicholas Futules - Vice President, District 7 (Via Telephone) Heather S. Heidelbaugh - Council-At-Large Thomas Baker - District 1 Jan Rea - District 2 Edward Kress - District 3 Michael J. Finnerty - District 4 Sue Means - District 5 John F. Palmiere - District 6 Dr. Charles J. Martoni - District 8 Robert J. Macey - District 9 William Russell Robinson - District 10 Terri Klein - District 11 James Ellenbogen - District 12 (Via Telephone) Amanda Green Hawkins - District 13 (Via Telephone) Allegheny County Courthouse Fourth Floor, Gold Room 436 Grant Street Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15219 Tuesday, November 17, 2015 - 5:00 p.m. SARGENT'S COURT REPORTING SERVICE, INC. 429 Forbes Avenue, Suite 1300 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 (412) 232-3882 FAX (412) 471-8733 IN ATTENDANCE: William McKain - Allegheny County Manager Joseph Catanese - Director of Constituent Services Jared Barker - Director of Legislative Services Walter Szymanski - Budget Director Jack Cambest - Council Solicitor PRESIDENT DEFAZIO: We're going to lead off with the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag, and then remain standing for silent prayer or reflection, but I want you to remember what's happened in Paris and other parts, the tragedies there in your prayers, so I'll start off with the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag. (Pledge of Allegiance recited.) (Moment of Silent Prayer or Reflection.) PRESIDENT DEFAZIO: We'll have a roll call. MR. CATANESE: Mr. Baker? MR. BAKER: Here. MR. CATANESE: Mr. Ellenbogen? MR. ELLENBOGEN: Here. MR. CATANESE: Mr. Finnerty? MR. FINNERTY: Here. MR. CATANESE: Mr. Futules? MR. FUTULES: Here. MR. -

Driving Directions to the New Hazlett Theater: from Downtown

Driving Directions to the New Hazlett Theater: From Downtown Pittsburgh • Cross Andy Warhol Bridge (formerly 7th Street Bridge) • Continue on Sandusky Street through 3 stoplights to Allegheny Center, roughly 4 blocks • Sandusky Street becomes East Commons • Continue straight 1 block on East Commons, shifting to left lane • Continue through stoplight, taking immediate left onto Allegheny Square East • Parking is along the street From Airport and West • Take 279 North to Pittsburgh • At downtown, take Ft. Duquesne Bridge • Follow signs for 279 North, which will require transferring to far right lanes • Exit at Rt 28 N/Chestnut Street/E. Ohio Street Exit • Stay to the left and immediately exit at E. Ohio Street Exit • At first stoplight, turn left onto E. Ohio Street • Continue 4 blocks through the business district and continue driving straight at stoplight • At next stoplight, turn gradual right into traffic circle at East Commons and take immediate left into Allegheny Square East • Parking is along the street From Monroeville (Turnpike exit #6), Oakland, Squirrel Hill • Take 376 to Pittsburgh • Follow North Shore exits, across Ft. Duquesne Bridge • Follow signs for for 279 North, which will require transferring to far right lanes • Exit at Rt 28 N/Chestnut Street/E. Ohio Street Exit • Stay to the left and immediately exit at E. Ohio Street Exit • At first stoplight, turn left onto E. Ohio Street • Continue 4 blocks through the business district and continue driving straight at stoplight • At next stoplight, turn gradual right into traffic circle at East Commons and take immediate left into Allegheny Square East • Parking is along the street From points North • 279 South to Downtown • Exit at East Street Exit • Continue straight through 2 stoplights and turn right at 3rd stoplight at E. -

G-20 Protest Events

The city of Pittsburgh has gotten 20 requests for permits for activities surrounding the G-20 summit. G-20 protest events CROWD DATE OF EVENT DATES TIME PLACE EXPECTED GROUP OR GROUPS WEB SITE APPLICATION CITY RESPONSE 1. Artists and Community Music Camp Sept. 18-26 All day and overnight South Side Riverfront Park 50 Pittsburgh Outdoor Artists N/A July 29 Permitted for daytime only — no camping 2. Bail Out the People Living Wage Vigil Sept. 19-25 All day and overnight East Park, on the North Side 500 to 1,000 Bail Out the People Movement Bailoutthepeople.org July 2 Permitted for daytime only — no camping 3. Bail Out the People March for Jobs Sept. 20 Noon to 6 p.m. Hill District to Convention Center 500 to 1,000 Bail Out the People Movement Bailoutthepeople.org July 31 Preliminarily approved 4. G 6 Billion Journey and Witness walk Sept. 20 2 p.m. to unknown Smithfield United Church of Christ, 500 G 6 billion, a coalition of 11 religious G6billion.org Aug. 27 No final city response Downtown, to Convention Center or social justice organizations yet —approval anticipated 5. Codepink Women for Peace Tent City Sept. 20-25 All day and overnight Point State Park 100 to 150 Codepink Pittsburgh Women for Peace Codepink4peace.org Aug. 12 No city decision yet 6. Three Rivers Climate Convergence Camp Sept. 20-25 All day and overnight Point State Park 4,000 Three Rivers Climate Convergence 3riversconvergence.org August No city decision yet 7. Three Rivers Climate Convergence Camp Sept. -

Grant Street-3/28/06

Downtown Pittsburgh Walking Tour 1. Renaissance Pittsburgh There’s nothing like walking to get you in touch Hotel with a place. You see, hear, notice, explore, Bridges & River Shores 2. Byham Theater 13 11 and discover. 3. Roberto Clemente, 13 ––Laurence A. Glasco, author, historian, and PHLF Trustee 10 Andy Warhol, and 3 Rachel Carson Bridges 4. Allegheny River N 12 15 FREE TOURS & EVENTS 14 5. Fort Duquesne Bridge 9 3 15 Old Allegheny County Jail Museum 6. Heinz Field 8 Open Mondays through October ( 11:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.) 8 (except for court holidays) 7. PNC Park 7 3 Downtown Pittsburgh and Oakland: Guided Walking Tours 8. Roberto Clemente and Every Friday, May through October Willie Stargell Statues • 2 Two different free walking tours are offered each month: 9. Allegheny Landing 1 4 one from 10 a.m. to 11 a.m. and another from Noon to 10. Alcoa/Arconic 1 p.m. Join us for one, or both. • Advance reservations are appreciated (see below) . 11 . Andy Warhol Museum 12 . Downtown Pittsburgh DOWNTOWN’S BEST Skyscrapers (view) 6 5 Special Places and Spaces in a 2 1/2-Hour Walk 13 . David L. Lawrence Not free. Advance paid reservations are required (see below) . Convention Center June through August: every Thursday, 9:45 a.m. to Noon. 14 . Pittsburgh CAPA Other dates by appointment for groups of 10 people. (Creative and Performing Arts) 6 –12 SPECIAL TOURS & MEMBERSHIP 15 . Allegheny Riverfront A self-guided walking tour, compliments Park Visit www.phlf.org and click on Tours & Events to find out about neighborhood walking tours in the of the Pittsburgh History & Pittsburgh region, April through October. -

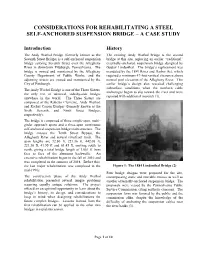

Considerations for Rehabilitating a Steel Self-Anchored Suspension Bridge – a Case Study

CONSIDERATIONS FOR REHABILITATING A STEEL SELF-ANCHORED SUSPENSION BRIDGE – A CASE STUDY Introduction History The Andy Warhol Bridge (formerly known as the The existing Andy Warhol bridge is the second Seventh Street Bridge) is a self-anchored suspension bridge at this site, replacing an earlier “traditional” bridge carrying Seventh Street over the Allegheny externally-anchored suspension bridge designed by River in downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The Gustav Lindenthal. The bridge’s replacement was bridge is owned and maintained by the Allegheny mandated by the 1889 River and Harbor Act, which County Department of Public Works, and the required a minimum 47-foot vertical clearance above adjoining streets are owned and maintained by the normal pool elevation of the Allegheny River. This City of Pittsburgh. earlier bridge’s design also revealed challenging subsurface conditions when the northern cable The Andy Warhol Bridge is one of the Three Sisters, anchorages began to slip toward the river and were the only trio of identical, side-by-side bridges repaired with additional masonry (1). anywhere in the world. The Three Sisters are composed of the Roberto Clemente, Andy Warhol, and Rachel Carson Bridges (formerly known as the Sixth, Seventh, and Ninth Street Bridges, respectively). The bridge is comprised of three simple-span, multi- girder approach spans and a three-span continuous self-anchored suspension bridge main structure. The bridge crosses the Tenth Street Bypass, the Allegheny River and several riverfront trails. The span lengths are 72.80 ft, 221.36 ft, 442.08 ft, 221.36 ft, 41.95 ft and 61.45 ft, moving south to north, giving a total bridge length of 1,061 ft from face to face of the abutment backwalls.