Encountering Pain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kettering General Hospital Nhs Foundation Trust in Association with Eastman Dental Hospital and Institute University College London Hospitals Nhs Foundation Trust

KETTERING GENERAL HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST IN ASSOCIATION WITH EASTMAN DENTAL HOSPITAL AND INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST SPECIALIST REGISTRAR POST IN ORTHODONTICS JOB DESCRIPTION 2021 APPOINTMENT This job description covers a full-time non-resident Specialist Registrar post in Orthodontics. The duties of this post will be split between Kettering General Hospital and the Eastman Dental Institute, with three days spent in Kettering and two days in the Eastman Dental Institute. This post will be based administratively at the Trent Deanery, Sheffield. The Postgraduate Dental Dean has approved this post for training on advice from the SAC in Orthodontics. The posts have the requisite educational and staffing approval for specialist training leading to a CCST and Specialist Registration with the General Dental Council. The successful candidate will be required to register on the joint training programme leading to the M.Orth.RCS and the MClin.Dent. in Orthodontics at the University of London (unless they already hold equivalent qualifications). This appointment is for one year in the first instance, renewable for a further two years subject to annual review of satisfactory work and progress. Applicants considering applying for this post on a Less Than full Time (flexible training) basis should initially contact the Postgraduate Dental Dean’s office in Sheffield for a confidential discussion. QUALIFICATIONS/EXPERIENCE REQUIRED Applicants for specialist training must be registered with the GDC, fit to practice and able to demonstrate that they have the required broad-based training, experience and knowledge to enter the training programme. Applicants for orthodontics will be expected to have had a broad based training including a period in secondary care, ideally in Oral and Maxillofacial surgery and paediatric dentistry and to have completed a 2 year period of General Professional Training. -

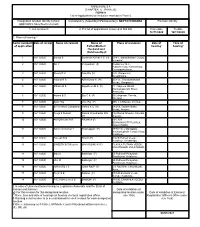

(CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for Inclusion

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): NEYYATTINKARA Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 Soniya S Santhosh Kumar V S (H) 09/81 , Manalithottam Colony, Venpakal, , 2 16/11/2020 Ani V Velayudhan (F) Kodannoor Mele, PuthanVeedu, Punnakkadu, Perumpazhuthoor , , 3 16/11/2020 Blessy D V Sam Raj (H) 220, Vlangamuri, Neyattinkara, , 4 16/11/2020 Rajimol R S Ajith Kumar S (H) 25/113 , Thunduthattuvila Veedu, Vlangamuri, , 5 16/11/2020 Afthab Ali S Sajudheen M A (F) 441 Sajeena Manzil, Narayanapuram Street, Amaravila, , 6 16/11/2020 Anjana B S Biju C K (F) 682 Anjanam, Ponvila, Chenkal, , 7 16/11/2020 Ajolin Raj Jose Raj (F) 565, J A Bhavan, Chenkal, , 8 16/11/2020 Sreelekshmi Ganapathy Vishnu K G (H) 08/259, Vadakkethattu Veedu, Arayoor, , 9 16/11/2020 Reeja S Ressal Rassal Chandradas N S 422 Rassal Bhavan, Chenkal, (H) Arayoor, , 10 16/11/2020 ANTORAJAN R R RAJAN A (F) 491, R R BHAVAN,KUTTIPLAVILA, KULATHOOR, , 11 16/11/2020 Satheesh Kumar T Thankappan (F) 17/501 Dev Mangalam, Bhanamughath Temple Road, Kulathoor, , 12 16/11/2020 Bineesh B S Binu K (F) Plavila Puthen Veedu, Kulathoor, Uchakkada, , -

Career Satisfaction and Work-Life Balance of Specialist Orthodontists Within the UK/ROI

Career satisfaction and work-life balance of specialist orthodontists within the UK/ROI Sama M. Al-Junaida, Samantha J. Hodgesb, Aviva Petriec, Susan J. Cunninghamd a. Honorary Specialty Registrar in Orthodontics Email: [email protected] UCL Eastman Dental Institute, London, United Kingdom b. Consultant in Orthodontics Email: [email protected] Eastman Dental Hospital, University College London Hospitals (UCLH) Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom c. Honorary Reader in Biostatistics Email: [email protected] UCL Eastman Dental Institute, London, United Kingdom d. Professor/Honorary Consultant in Orthodontics Email: [email protected] UCL Eastman Dental Institute, London, United Kingdom 1 Abstract: Objectives: To investigate factors affecting career satisfaction and work-life balance in specialist orthodontists in the UK/ROI. Design and setting: Prospective questionnaire-based study. Subjects and methods: The questionnaire was sent to specialist orthodontists who were members of the British Orthodontic Society. Results: Orthodontists reported high levels of career satisfaction (median score 90/100). Career satisfaction was significantly higher in those who exhibited: i) satisfaction with working hours ii) satisfaction with the level of control over their working day iii) ability to manage unexpected home events and iv) confidence in how readily they managed patient expectations. The work-life balance score was lower than the career satisfaction score but the median score was 75/100. Work-life balance scores were significantly affected by the same four factors, but additionally was higher in those who worked part time. Conclusions: Orthodontists in this study were highly satisfied with their career and the majority responded that they would choose orthodontics again. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

Orthodontic Training Programme Job Description

Orthodontic Training Programme Job Description Post Details HEE Office: London Job Title: Specialty Trainee in Orthodontics ST1 Person Specification: NRO to complete Full time Hours of work & nature of Contract: Fixed Term Training Appointment Main training site: Eastman Dental Hospital Other training site(s): Organisational Arrangements Training Programme Director (TPD): Claire Hepworth TPD contact details: Claire Hepworth Consultant Orthodontist Ashford and St.Peters NHS Trust London Road Ashford Middx TW15 3AA University: University College London (UCL) Degree MClinDent (Masters in Clinical Dentistry) awarded: Time Years 1 and 2: full time study for the MClinDent commitment: Year 3: full time study in the post-MClinDent Affiliate year (also registered with UCL and fees are payable) University base University fees: 2020/21 What What What fee 2020/21: will I will I will I https://www.ucl.ac.uk/students/fees- pay in pay in pay in and-funding/pay-your-fees/fee- st nd rd schedules/2020-2021/postgraduate- 1 2 3 taught-fees-2020-2021 year? year? year? https://www.ucl.ac.uk/students/fees-and- funding/pay-your-fees/fee- schedules/2020-2021/postgraduate- affiliate-fees-2020-2021 Page | 1 Details of fees for the current academic year can be found on the UCL websites shown NB: Fees on the websites shown are for the current academic year only and will be subject to increases in accordance with UCL fee structures Bench fees 2018/17: Training Details (Description of post) The programme is full-time, and includes lectures, demonstrations, diagnostic clinics and seminars, in addition to supervised practical treatment of patients teaching the basic principles of the theoretical and practical aspects of orthodontics. -

University College London Hospitals Nhs

Title: JOB DESCRIPTION Specialty Registrar in Paediatric Dentistry Directorate: RNTNEH Board/corporate function: Specialist Hospitals Responsible to: Clinical Lead Accountable to: Clinical Director Hours: 10 PA (40 hours per work) Location: Paediatric Dentistry UNVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH), situated in the West End of London, is one of the largest NHS trusts in the United Kingdom and provides first class acute and specialist services both locally and to patients from throughout the UK and abroad. The new state-of-the-art University College Hospital which opened in 2005, is the focal point of the Trust alongside six cutting-edge specialist hospitals. UCLH was one of the first trusts to gain foundation status. The Trust has an international reputation and a tradition of innovation. Our excellence in research and development was recognised in December 2006 when it was announced that, in partnership with University College London (UCL), we would be one of the country’s five comprehensive biomedical research centres. The Trust is closely associated with University College London (UCL), a multi-faculty university. The Royal Free & University College Medical School (RFUCMS), which is one of the highest rated medical schools in the country, forms the largest element of the Faculty of Biomedical Sciences (FBS), which was formed on 1st August 2006. FBS comprises the former Faculty of Clinical Sciences, four postgraduate Institutes (Ophthalmology, Neurology, Child Health, Eastman Dental) and the Wolfson Institute for Biomedical Research. This structural change further enhances the exceptionally strong base of research and teaching in Biomedicine at UCL. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Governing Public Hospitals.Indd

Cover_WHO_nr25_Mise en page 1 17/11/11 15:54 Page1 25 REFORM STRATEGIES AND THE MOVEMENT TOWARDS INSTITUTIONAL AUTONOMY INSTITUTIONAL TOWARDS THE MOVEMENT AND STRATEGIES REFORM GOVERNING PUBLIC HOSPITALS GOVERNING Governing 25 The governance of public hospitals in Europe is changing. Individual hospitals have been given varying degrees of semi-autonomy within the public sector and empowered to make key strategic, financial, and clinical decisions. This study explores the major developments and their implications for national and Public Hospitals European health policy. Observatory The study focuses on hospital-level decision-making and draws together both Studies Series theoretical and practical evidence. It includes an in-depth assessment of eight Reform strategies and the movement different country models of semi-autonomy. towards institutional autonomy The evidence that emerges throws light on the shifting relationships between public-sector decision-making and hospital- level organizational behaviour and will be of real and practical value to those working with this increasingly Edited by important and complex mix of approaches. Richard B. Saltman Antonio Durán The editors Hans F.W. Dubois Richard B. Saltman is Associate Head of Research Policy at the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, and Professor of Health Policy and Management at the Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University in Atlanta. Hans F.W. Dubois Hans F.W. Antonio Durán, Saltman, B. Richard by Edited Antonio Durán has been a senior consultant to the WHO Regional Office for Europe and is Chief Executive Officer of Técnicas de Salud in Seville. Hans F.W. Dubois was Assistant Professor at Kozminski University in Warsaw at the time of writing, and is now Research Officer at Eurofound in Dublin. -

'Reversal of Chronic Pain by Activation of Single GABAA Receptor Subtypes'

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Reversal of chronic pain by activation of single GABAA receptor subtypes Ralvenius, William T Abstract: SUMMARY The ability to perceive pain is a basic property of humans and of all other higher order animals. The primary role of pain sensation and nociception (that is, the neuronal activity encoding pain) is to protect against potentially harmful threats arriving from the environment or the body interior. Pain can however also become dysfunctional and persist for extended periods of time without an appar- ent benefit, instead becoming a major burden that requires medical attention. Chronic pain isamajor socio-economic challenge, which – despite scientific advances in the understanding of its causes – remains poorly responsive to the drugs available on the market today. Recent insights into the mechanisms of chronic pain states suggest that a common factor for many kinds of persistent pain states is a loss of inhibition in spinal cord circuits that normally control nociceptive input to the brain. The so- called benzodiazepines – first marketed by Hoffmann-La Roche in the 1960s – are drugs that facilitate synaptic inhibition throughout the CNS and have as such the potential to reverse pathological disinhibition. Ben- zodiazepines facilitate inhibition by increasing the activity of -aminobutyric acid (GABA) at its receptor, a heteropentameric anion permeable ion channel. Although rodent studies have shown that pathologically increased pain sensitivity can be normalized by intrathecal (spinal) injection of benzodiazepines, these drugs do not exert clinically relevant analgesia in human patients, at least not after systemic application. -

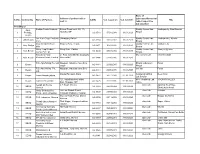

S.L.No. Commodity Name of Packers Address of Packers with E- Mail Id

Name of Address of packers with e- Laboratory/Comercial S.l.No. Commodity Name of Packers CA No. C.A. issued on C.A. valid till TBL mail id /SGL/Cooperative Lab attached R.O.Bhopal Aata, Poddar Foods Products Behind Rewa hotel, NH- 78, Quality Control Lab Vindhyavelly, Maa Birasani 1 Porridge, Shahdol, MP A/2 3518 07.08.2018 31.03.2023 Bhopal Besan Lav Kush Corp. Products Gairatganj, Raisen Quality Control Lab Vindhya velly, Ajiveka 2 Atta Besan A/2-3384 11.10.2013 31.03.2023 Com. Bhopal Maa GAYATRI Flour Khajuria Bina, Dewas Quality control Lab, Vindya Velly 3 Atta, Daliya A/2 3471 15.09.2016 31.03.2021 Mills Bhopal Sironj Crop Produce Sironj Distt- Vidisha Quality Control Lab Sironj & Ajjevika 4 Atta, Besan A/2-3404 03.03.2014 31.03.2019 Comp. Pvt. Ltd Bhopal Kaila Devi Food 21 Ram Janki Mandir Jiwajiganj Morena Ana Lab Chambal Gold 5 Atta, Besan Products Private Limited Morena MP A/2 3464 22/06/2016 31.03.2021 R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Ltd. Naugaon Industries Area Bina, Bhopal Laboratory Paras 6 Besan A/2-3444 26/06/2015 31/03/2020 Sagar Bhopal R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Naugoan, Industrial area,Bina own lab Paras 7 Besan A/2-3444 29.05.2015 31.03.2020 Ltd. Mauza Ramgarh, Datia Gwaliar Analytical Deep Gold 8 Besan Tiwari Masala Udyog A/2 3477 14.12.2016 31..03.2021 Lab,Gwaliar 121, Industrial Area, Maksi, MPP. Analytical Lab VINDHYA VALLEY 9 Besan Lakshmi Besan Mill A/2 3476 20.10.2016 31..03.2021 Distt. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2012 [Price: Rs. 28.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 37] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2012 Purattasi 3, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2043 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Change of Names .. 2325-2395 Notices .. 2240-2242 .. 1764 1541-1617 NoticeNOTICE .. 1617 NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 34603. My daughter, N. Rizwana, born on 12th November 34606. I, B. Vel, son of Thiru K. Bethuraj, born on 4th April 1996 (native district: Ramanathapuram), residing at 1967 (native district: Theni), residing at No. 63-NA, Vaigai No. 11-7B/68, New Ramnad Road, Visalam, Madurai- Colony, Anna Nagar, Madurai-625 020, shall henceforth be 625 009, shall henceforth be known as N. RISVANA BEGAM. known as B. VELUCHAMY. ï£Ã˜H„¬ê. B. VEL. Madurai, 10th September 2012. (Father.) Madurai, 10th September 2012. 34604. I, N. Radha, daughter of Thiru V. Navaneethan, 34607. I, N. Thirupathi, son of Thiru Narayanasamy, born born on 18th July 1991 (native district: Calcutta-West Bengal), on 7th June 1983 (native district: Dindigul), residing at residing at No. 1/65A, Katchaikatti, T. Vadipatti Taluk, Madurai-625 218, shall henceforth be known No. 1C, Melaponnakaram 2nd Street, Arapalayam Post, as N.