EMCC Workshop Literature October, 2013 a Compilation of Evidence‐Based and Best Practice Literature on Emergency Medical Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergency Medical Services EMT and Paramedicine

DIVISION OF HEALTH SCIENCES STUDENT HANDBOOK AND POLICY MANUAL With the EMS Programs Addendum Revised by faculty in April 2020 for the 2020-2021 Academic Year Table of Contents SECTION I: Introduction and Overview .........................................................................................7 Division of Health Sciences Mission Statement and Overview ..........................................8 Mission .....................................................................................................................8 Philosophy................................................................................................................8 Core Values ..............................................................................................................8 Division of Health Science Goals ........................................................................................9 Division of Health Sciences Program Accrediting Agencies ............................................10 SECTION II: Division of Health Sciences Policies ......................................................................12 Section A: Academic Policies ............................................................................................12 A.1.0 Attendance ...................................................................................................12 A.2.0 Student Progress ...........................................................................................12 A.3.0 Testing Policy ..............................................................................................13 -

Paramedicine Role Descriptions

Paramedicine Role Descriptions The following paramedical role descriptors have been developed by Paramedics Australasia to provide an introduction to the current clinical roles within Paramedicine in Australia and New Zealand. Within Paramedicine there are a variety of different clinical roles and scopes of practice. This work covers the broad classifications of professional, technical and communications streams of practice. Due to the current absence of national regulation in Australia and New Zealand, the scope of practice for individuals engaged within Paramedicine varies between jurisdictions, practice settings and engaging organisations. The different legislative frameworks in Australia and New Zealand give rise to local variations in practice such as, for example, controlled substances legislation. A paramedic serving in the Australian or New Zealand Defence Forces operates in accordance with the activities for which they have been given the authority to perform. This is determined by the individual’s education and competence, the environment in which they practice and the requirements of the relevant defence service. For those seeking employment within Paramedicine it is important to be aware that each organisation sets its own employment criteria and selects applicants on merit. The clinical roles currently found within Paramedicine are described below. PROFESSIONAL STREAM • Paramedic (Paramedic) • Intensive Care Paramedic (ICP) • Retrieval Paramedic (RP) • General Care Paramedic (GCP) TECHNICAL STREAM • First Responder (FR) • Patient Transport Attendant – Level 1 (PTA1) • Patient Transport Attendant – Level 2 (PTA2) • Basic Life Support Medic (BLSM) AMBULANCE COMMUNICATIONS STREAM • Emergency Medical Dispatch Support Officer (EMDSO) • Emergency Medical Dispatcher (EMD) Descriptor Sections Other vocational titles: A list of vocational titles used by Australasian paramedical services: public, private and defence. -

EMS Industry Trends | Cyber Liability | Employment Law Legislation

EMS Industry Trends | Cyber Liability | Employment Law Legislation S UMMER 2014 2014 Stars of Life Recipients | Annual Convention Plans Find out why others have trusted the Multi-Grip since 1989. The Multi-Grip was designed by a fire-fighter in 1989. Today this effective CID is used across the US as well as in other countries. It comes in three sizes: adult, child and pediatric. This is a complete system for your head immobilization needs. Its design makes it a universal head immobilizer appropriate for a variety of situations. Based on a truss system, the Multi-Grip maintains superior strength, and any patient movement will tighten the straps to create the ultimate immobilization. It’s simple and it works. Home of the Tank Boss Portable O2 Cylinder Lift Manufacturing Find out why others have trusted the Multi-Grip since 1989. The Multi-Grip was designed by a fire-fighter in 1989. Today this effective CID is used across the US as well as in other countries. It comes in three sizes: adult, child and pediatric. This is a complete system for your head immobilization needs. Its design makes it a universal head immobilizer appropriate for a variety of situations. Based on a truss system, the Multi-Grip maintains superior strength, and any patient movement will tighten the straps to create the ultimate immobilization. It’s simple and it works. Home of the Tank Boss Portable O2 Cylinder Lift Manufacturing S UMMER 2014 CAA Vision Assure delivery of excellent pre-hospital care to the people of California by promoting recognized industry best practices. -

Evidence-Based Performance Measures for Emergency Medical Services Systems:Amodel for Expanded Ems Benchmarking Astatement Developed by the 2007 Consortium U.S

SPECIAL CONTRIBUTIONS EVIDENCE-BASED PERFORMANCE MEASURES FOR EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES SYSTEMS:AMODEL FOR EXPANDED EMS BENCHMARKING ASTATEMENT DEVELOPED BY THE 2007 CONSORTIUM U.S. METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITIES’ EMS MEDICAL DIRECTORS (APPENDIX) J. Brent Myers, MD, MPH, Corey M. Slovis, MD, Marc Eckstein, MD, MPH, Jeffrey M. Goodloe, MD, S. Marshal Isaacs, MD, James R. Loflin, MD, C. Crawford Mechem, MD, Neal J. Richmond, MD, Paul E. Pepe, MD, MPH ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION There are few evidence-based measures of emergency medi- Evidence-based clinical measures of emergency med- cal services (EMS) system performance. In many jurisdictions, ical services (EMS) system performance have been response-time intervals for advanced life support units and few in number, largely due to the limited quantity resuscitation rates for victims of cardiac arrest are the pri- and quality of research committed to the prehospital mary measures of EMS system performance. The association arena.1−4 Although there is a 9-1-1 call for EMS of the former with patient outcomes is not supported explic- response every other second in the United States, itly by the medical literature, while the latter focuses on a very and despite the fact that survival from various acute small proportion of the EMS patient population and thus does not represent a sufficiently broad selection of patients. While illnesses and injuries are determined in that prehos- For personal use only. these metrics have their place in performance measurement, pital setting, evidence for out-of-hospital emergency 1−3 a more robust method to measure and benchmark EMS per- care procedures are clearly lacking. -

Blueprint for Community Paramedicine Programs

Contents South Carolina Office of Rural Health ........................................................................................................... 5 Credits ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Purpose and the “How To” Section ....................................................................................................... 7 Purpose: .................................................................................................................................................... 7 How To: ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Version 1: The Abbeville Experience ............................................................................................................. 8 Abbeville Community Paramedicine Program .......................................................................................... 8 Abbeville's Community Paramedics .......................................................................................................... 8 The Abbeville Story ................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction to Community Paramedicine Programs ................................................................................. 10 Community Paramedicine ...................................................................................................................... -

Paramedicine and Telemedicine Resources

ASPR TRACIE Technical Assistance Request Requestor: Requestor Phone: Requestor Email: Request Receipt Date (by ASPR TRACIE): 21 February 2017 Response Date: 23 February 2017 Type of TA Request: Standard Request: The ASPR TRACIE Team was asked to collect resources related to the methods in which healthcare personnel and emergency medical service (EMS) providers are assessing and more efficiently providing needed services to the community. Response: The ASPR TRACIE team conducted an online search for community access to healthcare, barriers to healthcare access, improving healthcare access, telemedicine to improve healthcare access, and community paramedicine. We also reviewed existing ASPR TRACIE Topic Collections for materials on these subjects; namely, the Pre-Hospital and Virtual Medical Care Topic Collections. Resources gathered are listed below. Section I: Community Paramedicine Section II: Telemedicine Resources: Applications for Telemedicine and Lessons Learned Section III: Telemedicine Resources: Call Centers and Triage Lines Section IV: Telemedicine Resources: General Information Section V: Telemedicine Resources: Plans, Tools, and Templates Section VI: Resources Related to Community Access to Health Care Section VII: Agencies and Organizations Section VIII: Subject Matter Experts I. Community Paramedicine Resources Beck, E., Craig, A., Beeson, J., et al. (n.d.). Mobile Integrated Healthcare Practice: A Healthcare Delivery Strategy to Improve Access, Outcomes, and Value. American College of Emergency Physicians. (Accessed 2/22/2017.) The authors of this document propose a delivery strategy for an inter-professional practice of medicine – Mobile Integrated Healthcare Practice (MIHP). It is intended to serve a range of patients in the out-of-hospital setting by providing 24/7 needs based at- home, integrating acute care, chronic care, and prevention services. -

ET3 and Community Paramedicine: Quality Care, Right Time, Right Place

ET3 and Community Paramedicine: Quality Care, Right Time, Right Place Unnecessary trips to the emergency department put a significant burden on the U.S. healthcare system – for patients facing rising health insurance prices, for clinical teams dealing with shortages and for first responders tackling a high volume of 911 calls. Emergency Triage, Treat and Transport (ET3) is a voluntary CMS initiative that financially rewards participants for appropriately utilizing emergency medical services. Coupled with Community Paramedicine (CP), which dispatches a caregiver following non-emergent 911 calls to address care needs, these programs increase EMS efficiency and deliver a patient-centered approach to emergency response by delivering the right care at the right time in the right place. Envision Physician Services participates in both ET3 and CP. Our programs enhance care quality and improve patient experience at lower costs than traditional emergency department models. Our National Network, Powered by Virtual Health Through Envision Virtual Health Services, we use two-way real-time audio/video and leverage partnerships with public and private EMS services to bring local emergency responders together with our national network of more than 60 EMS medical directors and 3,500 board-certified emergency medicine clinicians serving more than 100 U.S. counties and 20 million patients. Benefits Features ■ Quick access to experienced clinicians ■ Experienced EMS and virtual health provider with record ■ Quality care when and where it is needed of high -

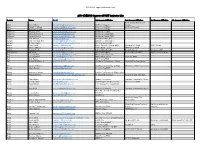

2018 KYEMSC Approved PAHT Instructor List

2017 PAHT Approved Instructor List 2018 KYEMSC Approved PAHT Instructor List County Name Email 1st Agency Affiliation 2nd Agency Affiliation 3rd Agency Affiliation 4th Agency Affiliation Adair County Ambulance Adair Donald Hare [email protected] Air Evac Lifeteam Service Adair Joseph C Wheet [email protected] Adair County EMS Air Evac Lifeteam Adair Thomas P Gaskin [email protected] Adair County EMS Anderson Amanda Short [email protected] Anderson Co EMS Anderson Amanda Womack [email protected] Anderson County EMS Anderson Susan Johnson [email protected] Anderson County EMS Ballard Jack Glisson [email protected] Ballard County EMS Ballard James P. Garrett II [email protected] Ballard Co. Ambulance Ballard Michael Clarke [email protected] Mercy Regional EMS Barren Kevin Jandt [email protected] Barren Metcalfe County EMS Glasgow Fire Dept SFRT Area4 Barren Ronnie Stinson [email protected] Park City Fire Dept SFRT Area 4 064 Barren Sammy Stotts [email protected] Barren Metcalfe EMS KCTCS Area 4 Green Co. EMS Barren/Allen Bill Milan [email protected] Allen County EMS Barren-Metcalfe EMS WKU Kemsa program Bell Dan Sanders [email protected] Middlesboro Fire Dept. Bell Gregory Fultz [email protected] SECC Middlesboro Claiborne EMS Bell Josh Peters [email protected] Bell County EMS Bell Robert M Wilson Jr [email protected] Southeast Community College Pineville Fire Department Bell Steven Robinson [email protected] Southeast Community College Middlesboro Fire Department Boone Adam Begley [email protected] Florence Fire/EMS Boone Anthony Scheben [email protected] Hebron Fire Protection District #106 Boone Benjamin Riley [email protected]; [email protected] St. -

Advanced Emergency Medical Technician & Paramedicine

ADVANCED EMERGENCY MEDICAL TECHNICIAN & PARAMEDICINE - CERTIFICATES APPLICATION PROCEDURE SUCCEED HERE The following procedures constitute the admissions process: PURPOSE OF PROGRAM 1. Submit an NMCC application along These certificate programs are designed to meet the needs for well-trained EMTs with a $20 application fee. and paramedics. The programs follow the National Emergency Medical Services Education Standards for Paramedic Education and meet or exceed the national 2. Submit offical high school transcript and/ or HiSET/GED scores (current senior’s standards for minimum clinical, didactic, lab and field externship hours and transcript should include completed competencies. The programs are offered with ongoing approval from the Maine ranking period grades). Emergency Medical Services, the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Professions (CAAHEP) and follow the standards and guidelines of the Committee 3. Official college transcripts for on Accreditation of Educational Programs for the Emergency Medical Services applicants who have attended other Professions (CoAEMSP). The core courses will simulate EMT and paramedic post-secondary schools. preparations, including studies of cardiac emergencies, emergency resuscitation, pharmacology, medical/legal issues, psychological emergencies, trauma, obstetrics 4. If SAT scores are not available, and gynecology, pediatrics, and neonatal care. In the hospital clinical component, placement testing will be required. students will observe, assess, and assist with care of medical, surgical and trauma patients; will administer medications; and will assist with diagnostic procedures. 5. Individual interview required. A campus tour is highly recommended. Clinical experiences will occur in pediatric, labor and delivery, emergency department, and critical care settings. Field experiences will allow the student to take the team leadership role at local services and in more urban settings. -

A Rapid Review of Pandemic Studies in Paramedicine

Review A rapid review of pandemic studies in paramedicine Nicola Cavanagh MSc(CritCare), is Senior Quality Assurance Strategist1,2; Walter Tavares PhD, is an Advanced Care Paramedic3,4; John Taplin BA, is an Advanced Care Paramedic1,2; Claire Hall BScN, is a Primary Care Paramedic1; Dale Weiss MA(Leadership), Advanced Care Paramedic, is Executive Director of EMS Operations1; Ian Blanchard PhD, Advanced Care Paramedic, is a scientist1,2 Affiliations: 1Alberta Health Services, Emergency Medical Services, Alberta, Canada 2Cumming School of Medicine, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada 3The Wilson Centre, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada 4University Health Network York Region Paramedic Services, Community Health Services Department, Canada https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.17.826 Abstract Introduction The spread of COVID-19 has challenged the paramedic community’s ability to provide health care, maintain personal safety, and implement evidence informed decisions and programs. The study objective was to examine the published literature related to paramedicine and pandemics. Methods A rapid review of research derived from an existing broad database of literature generated between 2006 and 2019 was used. We conducted a targeted secondary search of this database to identify studies of pandemics in paramedicine contexts and included three levels of screening. We used content analysis to identify broad themes and subthemes, and provide summaries and descriptions of each. Results From 54,638 -

Expanding the Roles of Emergency Medical Services Providers: a Legal Analysis

Expanding the Roles of Emergency Medical Services Providers: A Legal Analysis This report was made possible through funding from the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR). The report was researched and prepared for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials by faculty at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. James G. Hodge, Jr., JD, LLM Lincoln Professor of Health Law and Ethics Director, Public Health Law and Policy Program Arizona State University Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law Daniel G. Orenstein, JD Adjunct Professor and Fellow, Public Health Law and Policy Program Arizona State University Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law Kim Weidenaar, JD Fellow, Public Health Law and Policy Program Arizona State University Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law Association of State and Territorial Health Officials 2231 Crystal Drive, Suite 450 Arlington, VA 22202 202-371-9090 tel | 202-371-9797 fax www.astho.org Table of Contents Table of Abbreviations. 3 Acknowledgements . 3 Disclaimer . 3 Executive Summary/Introduction. .4 Project Limits. .4 Project Organization. .5 Table 1: “Top Options, Practices, or Solutions” in Law or Policy Re: Expanded EMS. .6 I. Setting the Stage: Brief Primer on Expanded EMS Practices . .8 State and Local Programs . .8 Federal Support for Public-Private Collaborations . .9 Future of Community Paramedicine and Mobile Integrated Healthcare . 10 II. Ready, Set, Go: Legal Issues Underlying Expanded EMS Activity Triggers . .11 1 Figure 1: Triggers for EMS Activities . .11 Authorizing and Establishing Protocols . .12 Coordinating Limited Resources. .14 Provision and Payment. .14 Limitations on Selection Among Competing Providers. -

Nevada Community Paramedicine Toolkit October 2019

Nevada Department of Health and Human Services Division of Public and Behavioral NEVADA Health With thanks to: COMMUNITY Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health - Emergency Medical Systems Minnesota Department of Health - Office of Rural Health and Primary Care Emerging Professions Program PARAMEDICINE Regional Emergency Medical Services Authority Nevada Rural Hospital Partners TOOLKIT Humboldt General Hospital TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. What is Community Paramedicine in Nevada and Why is it Necessary? 3. Starting a Community Paramedicine Program A) How to Get Started B) Regulations for Endorsement to Provide Community Paramedicine Services C) Application Process in Nevada D) Renewal for Endorsement to Provide Community Paramedicine E) Community Paramedicine Provider Qualifications F) Reporting 4. Education and Training A) Education Requirements B) Southern Nevada Health District Training Procedure for Community Paramedicine Services C) Community Paramedicine Courses 5. Community Paramedicine Programs in Practice A) Agencies with a Current Community Paramedicine Program in Nevada B) Community Paramedicine Program at REMSA C) Community Paramedicine in Critical Access Hospitals and Rural Health Clinics 6. Financing, Coverage and Limitations 7. References and Resources i 1. INTRODUCTION This toolkit is intended to be a resource for Nevada ambulance services, firefighting agencies and licensed hospitals interested in developing or expanding a Community Paramedicine program. The tools contained herein are intended to help streamline decision-making and the successful adoption of a Community Paramedicine program. The toolkit also includes references, resources, and examples to help planners get started quickly. 1 2. WHAT IS A COMMUNITY PARAMEDICINE PROGRAM AND WHY IS IT NECESSARY? Community Paramedicine is a fairly new healthcare delivery model.