PB Cover February 2010.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOWRAH VIVEKANANDA INSTITUTION Past Results Of

Code No. : 06046 (H.S.) PHONE No. : 033-2642-0385 Index No. : F1-067 [email protected] HOWRAH VIVEKANANDA INSTITUTION 75 & 77, SWAMI VIVEKANANDA ROAD P.O. SANTRAGACHI, HOWRAH-711 104 Past Results of School Leaving Exams In 1928, some students sat for the Entrance Examination conducted by the Calcutta University. The students appears at the Madhymik Examination conducted by the Board of Secondary Education. The Higher Secondary Examination (after class XI) was introduced in 1960. Later Madhyamik Examination and +2 course was introduced. The school which started with 55 students now boasts of more than three thousand students. Now the number of approved posts for teachers is ( 70 – 75) 6 posts are still lying vacant. The success rate for Class I to XII of the students in the Madhyamik Examination and Higher Secondary Examination is higher than the official average. The percentages of candidates passed the M.P. and H.S. examinations over the years has been consistently over 96%. A few times the numbers even did hit 100%. Many students have excelled in different examinations. Entrance Examination Debi Khan First 1950 Higher Secondary Vocational Examination Debobrata Hore First 1965 Higher Secondary Vocational Examination Aloke Kr. Basu Third 1965 Higher Secondary Vocational Examination Arun Chakraborty First 1967 Higher Secondary Vocational Examination Anupam Dey Tenth 1967 Higher Secondary Vocational Examination Maloy Mukherjee Fourth 1968 Higher Secondary Examination (Science) Manash Chattopadhyay Ninth 1970 Madhyamik Examination Barun Chakraborty Second 1982 Higher Secondary Indranil Chowdhury Nineteenth 1988 Madhyamik Examination Kingshuk Palodhi Fifth 1991 Higher Secondary Examination in Kingshuk Palodhi Fifth 1993 West Bengal Joint Entrance Examination Sanchyan Sen First 2005 Continued.. -

Howrah Vivekananda Institution 75 & 77, Swami Vivekananda Road P.O

Code No. : 06046 (H.S.) PHONE No. : 033-2642-0385 Index No. : F1-067 [email protected] HOWRAH VIVEKANANDA INSTITUTION 75 & 77, SWAMI VIVEKANANDA ROAD P.O. SANTRAGACHI, HOWRAH-711 104 OUR SCOUT GROUP The first troop of Vivekananda Institution Scouts Group was registered with the Boys Scouts association India on 17th September 1928. The managing committee believed that education as held by Swami Vivekananda is the manifestation of the qualities already in the man. Scouts echo the same objective of the man making in a practical form. Keeping with this view, the Scout movement was introduced in one of curricular subjects of the school. Scouting imparts knowledge to the boys apart from formal education, to make a good citizen, with a motto “Be Prepared”. To take apart in pulse Polio immunization programme, Road Safety Awareness programme, Anti Leprosy programme, to get exposure into adverse condition, to smile in difficulties, to take part in adventure life, making handicrafts, giving first aid, etc. The Scouts also take part in cultural programme like folk dance competition, Quiz competition, District level and State Level Competition, National Jamboree, World Jamboree. Since inspection the School Scout Group has been playing an important role in Swami Vivekanand’s Birth Day Ceremony, Rabindranath’s Birth Day Ceremony, Netaji’s Birthday Ceremony, Celebration of Independence Day and Republic Day etc. In the year of 1951, Scouts of the School were deputed as volunteer in the Parliament election of India. Scouts were rendered service in many occasions in Ramkrishna Vvekananda Ashram, Howrah and Belur Math. In every year Scouts camps are being held in different parts of the country. -

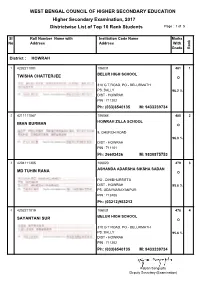

TOP 10 List of HOWRAH

WEST BENGAL COUNCIL OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION Higher Secondary Examination, 2017 Districtwise List of Top 10 Rank Students Page : 1 of 5 Sl Roll Number Name with Institution Code Name Marks No Address Address With Grade Rank District : HOWRAH 1 4202211001 106031 481 1 BELUR HIGH SCHOOL TWISHA CHATTERJEE O 310 G T ROAD, PO - BELURMATH PS.:BALLY 96.2 % DIST - HOWRAH PIN : 711202 Ph: (033)6540135 M: 9433239734 2 4211111047 106048 480 2 HOWRAH ZILLA SCHOOL IMAN BURMAN O 9, CHURCH ROAD 96.0 % DIST - HOWRAH PIN : 711101 Ph: 26603436 M: 9830875753 3 4204111305 106020 479 3 ASHANDA ADARSHA SIKSHA SADAN MD TUHIN RANA O PO - DIHIBHURSITTA DIST - HOWRAH 95.8 % PS.:UDAYNARAYANPUR PIN : 712408 Ph: (03212)953212 4 4202211019 106031 478 4 BELUR HIGH SCHOOL SAYANTANI SUR O 310 G T ROAD, PO - BELURMATH PS.:BALLY 95.6 % DIST - HOWRAH PIN : 711202 Ph: (033)6540135 M: 9433239734 Kalyan Sengupta Deputy Secretary (Examination) WEST BENGAL COUNCIL OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION Higher Secondary Examination, 2017 Districtwise List of Top 10 Rank Students Page : 2 of 5 Sl Roll Number Name with Institution Code Name Marks No Address Address With Grade Rank 5 4204111310 106020 476 5 ASHANDA ADARSHA SIKSHA SADAN SK AKIB UDDIN O PO - DIHIBHURSITTA DIST - HOWRAH 95.2 % PS.:UDAYNARAYANPUR PIN : 712408 Ph: (03212)953212 6 4211111015 106048 476 5 HOWRAH ZILLA SCHOOL CHAYAN MONDAL O 9, CHURCH ROAD 95.2 % DIST - HOWRAH PIN : 711101 Ph: 26603436 M: 9830875753 7 4218111311 106093 476 5 BAGNAN HIGH SCHOOL DIPANKAR MAITY O VILL & PO - BAGNAN DIST - HOWRAH 95.2 % PS.:BAGNAN -

North America Asia Pacific Europe Greater China Group Latin America Middle East and Africa

Participating IBM Z Academic Initiative Schools Educators from all over the world are teaching IBM Z mainframe technologies and building skills for the next generation. This is a partial listing of the most active schools listed by country, state or province. Attention: If you are interested in locating and recruiting new talent for internships and hiring, contact the educator listed or select the associated profile link to view curriculum details. Additional profiles will be added as available. For general inquiries about the IBM Z Academic Initiative program or if you're an educator who would like to be added to this list, email us at [email protected]. Click the below to go to a specific region: North America Asia Pacific Europe Greater China Group Latin America Middle East and Africa School Name Location Contact Profile North America Canada Nova Scotia Dalhousie University Halifax Michael Bliemel, Tony Schellinck Profile Ontario Durham College Oshawa Andrew Mayne Fanshawe College London Evan Lauersen Georgian College Barrie Greg Rodrigo Ryerson University Toronto Joshua Panar Profile St. Lawrence College Kingston Donna Graves Profile Quebec Cegep de Rimouski Rimouski Bruno Lavoie Cegep de Thetford Thetford Mines Marco Guay Profile Universite du Quebec en Outaouais Gatineau Stephane Gagnon Universite Laval Ville de Quebec Elisabeth Oudar United States Alabama Alabama State University Montgomery Kamal Hingorani School Name Location Contact Profile University of Alabama at Birmingham Birmingam Dr. Samuel Thompson New business certificate -

Complete List of Venues and Assigned Range of Roll Numbers of Clerkship Examination

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. P. MUKHERJEE ROAD, KOLKATA - 700 026 CLERKSHIP EXAMINATION (PART -I), 2019 Date of Examination : 25TH JANUARY, 2020 (SATURDAY) Subject : General Studies Time of Examination : 10:00 A.M. TO 11:30 A.M. & 2:00 P.M. TO 3:30 P.M. Name of Centre : ASANSOL (11) STD Code : 0341 Sl. Name of the Venues No. of Roll Nos. Roll Nos. No. Regd. (Forenoon (Afternoon Candts. Session) Session) D.A.V. HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) 1100001 1110371 1 BUDHA, P.O. ASANSOL,(NEAR HUTTON ROAD, RAMDHANI MORE) 500 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BURDWAN-713301 1100500 1110870 BIDHAN SMRITY SIKSHA NIKETAN (H.S.) 1100501 1110871 2 VILL. & P.O. DAMRA, PS-ASANSOL SOUTH 300 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BURDWAN - 713339 (NEAR JORA KALI MANDIR) 1100800 1111170 USHAGRAM GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) 1100801 1111171 3 G.T.ROAD, ASANSOL(OPP: B.B.COLLEGE) 450 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BARDHAMAN - 713 303 1101250 1111620 SANTINAGAR VIDYAMANDIR (H.S.) 1101251 1111621 4 SANTINAGAR, P.O. BURNPUR (NEAR BURNPUR BUS STAND), 360 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BURDWAN - 713325 1101610 1111980 RAHMATNAGAR HIGH SCHOOL (URDU) 1101611 1111981 5 RAHMATNAGAR, P.O. BURNPUR (NEAR RAHMATNAGAR MAZJID) 480 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BARDHAMAN - 713 325 1102090 1112460 ARYA KANYA UCHCHA VIDYALAYA (H.S.) 1102091 1112461 6 MURGASAL, NEAR - ARYA KANYA SCHOOL RD. 480 TO TO ASANSOL - 713303 1102570 1112940 ASANSOL DAYANAND VIDYALAYA (H.S.) 1102571 1112941 7 D.A.V.SCHOOL RD., BUDHA, ASANSOL 650 TO TO PIN - 713301 (NEAR D.A.V. HIGH SCHOOL) 1103220 1113590 SUBHASPALLI BIDYANIKETAN (H.S.) 1103221 1113591 8 SUBHAS PALLI MAIN ROAD, P.O. -

Swami Tyagishananda: Master Renunciate

Swami Tyagishananda: Master Renunciate By Vinayak Lohani Swami Tyagishananda was a sterling Sanyasin of the Ramakrishna Order and had a deep influence on many other future monks and spiritual aspirants who came in touch with him. In his life he combined the Karma, Bhakti, and Jnana in a way that was exemplary to other monks and spiritual practitioners. He was founder of the Thrissur Ashrama of the Ramakrishna Math and also spent a long time at the Bangalore Ashrama guiding younger monks and brahmacharins. Many young men joined the Ramakrishna Order inspired by him and under his mentorship. Early Life Tyagishanandaji’s pre-monastic name was V.K. Krishnan Menon and was born in the aristocratic Vadakke Kuruppam family in 1891. His family was socially very distinguished, and the Cochin Royal family had several nuptial ties with them. He did his schooling from Thrissur and thereafter completed intermediate in Sanskrit from what is now called Maharaja’s College at Ernakulum, which founded in 1875 and affiliated to the Madras University, was one of the oldest colleges in Southern India. He topped the whole University in this examination. 1 Thereafter he went to the renowned Presidency College Madras for his B.A., and thereafter M.A., in Sanskrit, where he was again the Gold Medalist. The Presidency College Madras, one of two of Presidency Colleges set up by the British (the other being in Kolkata), had a glorious history with a galaxy of distinguished alumni and faculty including the four ‘Bharat Ratnas’ – Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, C. Rajagopalachari, C.V. Raman, C. -

Swami Vivekananda's Leader-Management Model in The

PRAVRAJIKA BRAHMAPRANA Swami Vivekananda’s Leader-Management Model in the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission PRAVRAJIKA BRAHMAPRANA ho would have thought that application—beyond caste, creed, and Swami Vivekananda, recognized country in its service to the underprivileged. Win the Ramakrishna-Vedanta Furthermore, Vivekananda’s unitive tradition as a knower of Brahman and World experience, which unveiled his vision to Teacher, would be considered as a model in perceive the one Self in all, awoke within today’s world of leader-management? him a compassion for humankind which However, if we stop to consider what surpasses normal human empathy. In 1893, nirvikalpa samàdhi is—a unitive experience before leaving India for the Chicago that transcends body, mind and ego, coming Parliament of World Religions, back from which the knower experiences Vivekananda disclosed to his brother monk, one’s true Self (the âtman) as one with Swami Turiyananda, who preferred Brahman and the world as a manifestation of contemplative life to public service: Brahman—then we may begin to “‘Haribhai, I am still unable to understand comprehend how universal Vivekananda’s anything of your so-called religion.” Then vision was. It transformed the Swami’s outer with an expression of deep sorrow on his perception and became the transcendental countenance and intense emotion shaking field of his consciousness from which all his his body, he placed his hand on his heart and thoughts and actions rose and fell—a added, “But my heart has expanded very consciousness, universal in application to much, and I have learnt to feel. Believe me, I any sphere of life he chose to apply it, feel intensely indeed.” His voice was choked including the field of leader-management. -

MONOGRAPH on ICT in EDUCATION

MONOGRAPH ON ICT in EDUCATION Project Report 2016-17 Project Report INTEGRATING INFORMATION COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES IN EDUCATION In the State of West Bengal April, 2019 Submitted by :- ( The Director, SCERT, West Bengal) (SPC & Research Fellow, Grade-II, SCERT) THE LEAD DISTRICT COORDINATORS & THE HEADS OF THE DIETs: BANKURA, HOOGHLY, NADIA, NORTH 24 PGS, MALDA. TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Summary Project Progress Project Issues and Lessons Learned Project Next Steps List of Resource Persons List of Assistant Teachers Trained Selected Project Ideas and Success Stories PROJECT SUMMARY Project title: ICT IN EDUCATION FOR LEARNING AND TEACHING Sanction Order: 130(sanc)–SE (P&B)/TRG – 16/2013 dated 02.07.2015 and 224 (sanc) -SE (P+B) / TRG – 16 / 2013 (Part) dated 18.08.2015. Project duration: 2016 -2017 Extension(s) (if applicable): NA Executive agency: SCERT (WB), Deptt. of School Education, Govt. of West Bengal and Five DIETs: 1. DIET, Nadia 2. DIET, North 24 Pgs 3. DIET, Bankura 4. DIET, Hooghly and 5. DIET, Malda Implementing partner(s): INTEL, GOOGLE AND WTL (WEBEL Technology Ltd.) Total budget: Sanctioned budget :- 8856285/- Target : Physical :- I. 1 No. of SRT Training II. Five nos. of MRP Training III. 97 nos. of Teacher Training workshops. Human Resource :- IV. 15 SRTs. V. 194MRPs. VI. 3886 Secondary teachers VII. 1943 (543 +1400) such schools across the state where the ICT @ School scheme has been implemented. Coverage: Physical :- I. 1 No. of SRT Training II. Five nos. of MRP Training III. 97 nos. of Teacher Training workshops. Human Resource :- IV. 15 SRTs V. 172 MRPs VI. 3497 Secondary teachers VII. -

Avadhoot of Arbudachal

/iVADHOOT OF ARBUDACHAl Biography of Vimala Thakar Kaiser Irani Vimak Thakar Slvadfioot o f SirSucCacfiat SI ^io^ra-pfiy o f VimaCa Slvadfioot of SirbudacfiaC ^ ^iograpfiy of ^imata Kaiser Irani First Edition: 2004 ©KAlStR IRANI All rights Reserved Available at: Om Mani Padmi Hum 1 Spenta Society R.P.T.S. Post, Old Khandala Road Khandala, 410 302 (Mah) India Printed in India By Prabhat Printing Works 427, Gultekdi, Pune 411037 (Mah) JAvadfioot o f SirbudacfiaC C O O \£ T E ^ S (Preface viii Chapter One: Tlie SpirituaC^Heritage 3 Inheritance.................................................... ....... 4 Experiments in Childhood................................ 21 Home Atmosphere..............................................26 Basic Truths Learnt in Childhood................... 34 Chapter ^luo: ‘The SpirituaC ^Foundation ... 47 Spiritual Foundation...........................................50 Early Consciousness...........................................56 Rishikesh Experiment..................................... ...66 Meeting with Saints...................................... .......77 Chapter ^hree: ContriSuting ‘To The T>eve[opment O f ‘Women 91 Non Sexual Consciousness................................95 Equalit)^ of Education........................................ 101 Choosing Independence............................... .....105 Marriage Offers...................................................109 Leaving H om e.....................................................117 chapter O^our Contributing ‘To Sociaf Change 131 Joining Bhoodan.............................................. -

January 2020 Words to Inspire “Do Not Spend Your Energy in Talking, but Meditate in Silence.” --- Swami Vivekananda the Ideal of Service

Vedanta Society of Toronto (Ramakrishna Mission) 120 Emmett Ave. Toronto, ON M6M 2E6 CANADA Tel.: 416-240-7262; Email: [email protected]; Website: www.vedantatoronto.ca Newsletter January 2020 Words to Inspire “Do not spend your energy in talking, but meditate in silence.” --- Swami Vivekananda The Ideal of Service Swamiji was dhyanasiddha (an adept in meditation) wherever they went. Since then the custom of asking from his very birth. So he gave importance to spiritual a monk for medicine is prevailing even now. Ashoka practices like japa-dhyana. But he cautioned and other followers of Buddha established many everybody that selfishness should not swallow us in service centres. Large-scale service work came into the name of spiritual practice. If we live together we vogue since then. shall get liberation together, or we shall drown When the monks of the Ramakrishna Order first together. Swamiji has said, "So long as a single man engaged themselves in service activities like running remains in bondage, I do not desire my own hospitals and schools, helping distressed people liberation". The Master also has said, "I shall have to during calamities like famine, drought, flood, etc., the come again and again for the emancipation of this monks of orthodox monastic orders did not appreciate world". The previous monastic organizations engaged it although they too were benefited by those services. themselves only in preaching Vedanta or various other Their view was that these monks deviated from the ideals they followed. Their activities were confined to ideal of monastic life. Swamiji had sent two of his the sphere of religion. -

Allotment of Seats for Higher Secondary Examination, 2019

Allotment of Seats For Higher Secondary Examination 2019 List may be changed for final verification on 25th February, 2019 INST. FEMALE EXAMINATION CENTER REG DISTRICT INSTITUTION NAME MALE EXAMINATION CENTER (Venue) CODE (Venue) 1 ALIPURDUAR 208005 ALIPURDUAR COLLEGIATE SCHOOL ALIPURDUAR GOBINDA HIGH SCHOOL ALIPURDUAR GOBINDA HIGH SCHOOL ALIPURDUAR JUNCTION RLY. GIRLS ALIPURDUAR JUNCTION 1 ALIPURDUAR 208006 HIGH SCHOOL SHYAMAPRASAD VIDYAMANDIR ALIPURDUAR JUNCTION RLY. HIGH ALIPURDUAR JUNCTION 1 ALIPURDUAR 208007 SCHOOL SHYAMAPRASAD VIDYAMANDIR MC. WILLIAM HIGHER SECONDARY ALIPURDUAR HINDI MADHYAMIK 1 ALIPURDUAR 208008 ALIPURDUAR HIGH SCHOOL H.S SCHOOL VIDYALAYA ALIPURDUAR NEW TOWN GIRLS' HIGH 1 ALIPURDUAR 208009 ALIPURDUAR GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL SCHOOL BIRPARA SHREE MAHAVIR HINDI HIGH BIRPARA SHREE MAHAVIR HINDI HIGH 1 ALIPURDUAR 208013 BIRPARA HIGH SCHOOL (H.S) SCHOOL SCHOOL 1 ALIPURDUAR 208018 FALAKATA HIGH SCHOOL JADABPALLI HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) JADABPALLI HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) PARANGERPAR SISHU KALYAN HIGH PARANGERPAR SISHU KALYAN HIGH 1 ALIPURDUAR 208020 JADABPALLI HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) SCHOOL SCHOOL 1 ALIPURDUAR 208025 JATESWAR HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) KHIRERKOTE HIGH SCHOOL KHIRERKOTE HIGH SCHOOL KAMAKHYAGURI MISSION HIGH 1 ALIPURDUAR 208028 KAMAKHYAGURI HIGH SCHOOL (XII) KAMAKHAGURI GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL SCHOOL MAHAKALGURI MISSION HIGH 1 ALIPURDUAR 208030 LOKNATHPUR HIGH SCHOOL LOKNATHPUR HIGH SCHOOL SCHOOL MC. WILLIAM HIGHER SECONDARY 1 ALIPURDUAR 208032 ALIPURDUAR GOBINDA HIGH SCHOOL SCHOOL RANGALI BAZNA MOHAN SINGH HIGH 1 ALIPURDUAR 208036 MADARIHAT -

A Directory of the Ramakrishna-Sarada Vivekananda

Volume 15, No. 2 • Special Edition 2009 Address all correspondence and subscription orders to: American Vedantist, Vedanta West Communications Inc. PO Box 237041 New York, NY 10023 A Directory of the Ramakrishna-Sarada Email: [email protected] Vivekananda Movement in the Americas Volume 15 No. 2 Donation US$5.00 Special Edition 2009 (includes U.S. postage) american vedantist truth is one; sages call it variously e pluribus unum: out of many, one CONTENTS Encouraging Community among Vedantists.................2 Vivekananda’s Message to the West .............................3 Developing Vedanta in the Americas — An Interview with Swami Swahananda ..............5 A Directory of the Ramakrishna-Sarada-Vivekananda Movement in the Americas ...................................10 Reader’s Forum Question for this issue ......................................... 27 In Memoriam: Swami Sarvagatananda Swami Tathagatananda ........................................29 Response to Readers’ Forum Question in Spring 2009 issue Vivekananda and American Vedanta Sister Gayatriprana ...............................................34 The Interfaith Contemplative Order of Sarada Sister Judith, Hermit of Sarada ..............................36 MEDIA REVIEWS Basic Ideas of Hinduism and How It Is Transmitted Swami Tathagatananda Review by Swami Atmajnanananda ..................... 38 Beyond Tolerance: Searching for Interfaith Understanding in America Gustav Niebuhr Review by John Schlenck ..................................... 39 The Evolution of God Robert Wright