Claudia Dutson Phd by Practice Royal College of Art November

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

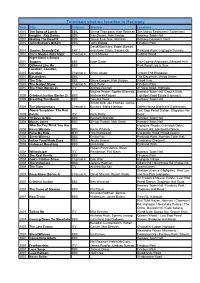

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

How Propaganda Works How Works

HOW PROPAGANDA WORKS HOW WORKS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS JASON STANLEY Princeton Oxford Copyright © 2015 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu Jacket design by Chris Ferrante Excerpts from Victor Kemperer, The Language of the Third Reich: LTI, Lingua Tertii Imperii, translated by Martin Brady © Reclam Verlag Leipzig, 1975. Used by permission of Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978– 0– 691– 16442– 7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2014955002 British Library Cataloging- in- Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro and League Gothic Printed on acid- free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This will always remain one of the best jokes of democracy, that it gave its deadly enemies the means by which it was destroyed. — JOSEPH GOEBBELS, REICH MINISTER OF PROPAGANDA, 1933– 45 CONTENTS Preface IX Introduction: The Problem of Propaganda 1 1 Propaganda in the History of Political Thought 27 2 Propaganda Defined 39 3 Propaganda in Liberal Democracy 81 4 Language as a Mechanism of Control 125 5 Ideology 178 6 Political Ideologies 223 7 The Ideology of Elites: A Case Study 269 Conclusion 292 Acknowledgments 295 Notes 305 Bibliography 335 Index 347 PREFACE In August 2013, after almost a decade of teaching at Rutgers University and living in apartments in New York City, my wife Njeri Thande and I moved to a large house in New Haven, Connecticut, to take up positions at Yale University. -

Libro CONFLICTOS ENTRE DERECHOS Digital.Pdf

Sistema Bibliotecario de la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación Catalogación PO C410.113 Conflictos entre derechos : ensayos desde la filosofía práctica / coordinadores C663c Miguel Ángel García Godínez, Diana Beatriz González Carvallo ; esta obra estuvo a cargo del Centro de Estudios Constitucionales de la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación ; presentación Ministro Arturo Zaldívar Lelo de Larrea ; introducción Ruth Chang .-- Primera edición. -- Ciudad de México, México : Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación, 2019. 1 recurso en línea (xxvii, 378 páginas). -- (Metodologías) ISBN 978-607-552-138-1 1. Colisión de derechos – Análisis 2. Aplicación de derechos fundamentales – Ponderación – Decisiones judiciales 3. Razón – Derecho 4. Principio de proporcionalidad – Normas – Valores – Ciudadanos – Jueces 5. Democracia – Condiciones sociales 6. Estado de Necesidad – Conflictos jurídicos I. García Godínez, Miguel Ángel, coordinador II. González Carvallo, Diana Beatriz, coordinador III. Zaldívar Lelo de Larrea, Arturo, 1959- , escritor de prólogo IV. Chang, Ruth, autor de introducción V. México. Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación. Centro de Estudios Constitucionales VI. serie LC KGF356.S85 Primera edición: enero de 2020 D.R. © Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación Avenida José María Pino Suárez núm. 2 Colonia Centro, Alcaldía Cuauhtémoc C.P. 06060, Ciudad de México, México. Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial por cualquier medio, sin autorización escrita de los titulares de los derechos. El contenido de esta obra es responsabilidad exclusiva de los autores y no representa en forma alguna la opinión institucional de la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación. Esta obra estuvo a cargo del Centro de Estudios Constitucionales de la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación. -

Make-‐Up and Hair Designer

KATE BENTON – MAKE-UP AND HAIR DESIGNER FEATURE FILM CREDITS INCLUDE: THE NUMBERS STATION Director: Kasper Barfoed Action Thriller Producers: Bryan Furst, Sean Furst, Nigel Thomas Locations: London, Morocco Featuring: John Cusack, Malin Akerman Make-Up Artist Liam Cunningham, Hannah Murray Designer: Graham Johnston Production Co: Echo Lake Ent / Furst Films Matador Pictures HUGO Director: Martin Scorsese Period Mystery Fantasy Drama (3D) Producers: Johnny Depp, Tim Headington Locations: Shepperton Studios, London, Paris Graham King, Martin Scorsese Key Make-Up Artist Featuring: Chloë Grace Moretz, Asa Butterfield Designer: Morag Ross Ben Kingsley, Sacha Baron Cohen Jude Law, Christopher Lee Production Co: Paramount Pictures/GK Films/Infinitum Nihil Academy Award Nomination for Best Picture Golden Globe Nomination for Best Motion Picture, Drama CLASH OF THE TITANS Director: Louis Letterier Action Adventure Fantasy Producers: Kevin De La Noy, Basil Iwanyk Locations: Pinewood/Shepperton Studios, Wales, Spain Featuring: Sam Worthington, Gemma Arterton Make-Up Artist in charge of a team of 8 and ran Liam Neeson, Ralph Fiennes 2nd Unit Make-Up Department Mads Mikkelsen, Luke Evans Designer: Jenny Shircore Production Co: Warner Brothers / Legendary Pictures THE YOUNG VICTORIA Director: Jean-Marc Vallée Period Historical Romantic Drama Producers: Tim Headington, Graham King Locations: Shepperton Studios Martin Scorsese Make-Up Artist, Hair Stylist Featuring: Emily Blunt, Rupert Friend Designer: Jenny Shircore Paul Bettany, Mark Strong Miranda -

Feminism in Philosophy

THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO FEMINISM IN PHILOSOPHY EDITED BY MIRANDA FRICKER Heythrop College, University of London AND JENNIFER HORNSBY Birkbeck College, University of London published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb22ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York ny 10011±4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia # Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in 10/13pt Sabon [ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data The Cambridge companion to feminism in philosophy / edited by Miranda Fricker and Jennifer Hornsby. p. cm. isbn 0 521 62451 7 (hardback). ± isbn 0 521 62469 X (paperback) 1. Feminism ± Philosophy. i. Fricker, Miranda. ii. Hornsby, Jennifer. hq1154.c25 2000 305.42'01±dc21 99±21117 cip isbn 0 521 62451 7 hardback isbn 0 521 62469 X paperback CONTENTS List of contributors page ix Preface xiii Introduction 1 miranda fricker and jennifer hornsby 1 Feminism in ancient philosophy: The feminist stake in Greek rationalism 10 sabina lovibond -

Meghan Trainor

34 Friday June 1 2018 hull-live.co.uk MAI-E01-S2 MAI-E01-S2 hull-live.co.uk Friday June 1 2018 35 TODAy’S TV With Sara Wallis SOUND OUT BEST OF THE REST Meghan Trainor arrived with the bubblegum-pop infused All About I took a break from SOUND That Bass, but JOE NERSSESSIAn JUDGEMENT discovers she is more THE LATEST ALBUM than just a one-trick pony RELEASES RATED social media for the AND REVIEWED EGHAN Trainor is used Graham Norton to collaborating with THE GRAHAM NORTON SHOW the likes of John Legend, Ariana Grande JULIANA DAUGHERTY BBC1 10.35pm – LIGHT DEFINITELY the best in the business right and Charlie Puth, but HHHHH for her upcoming album she now, Graham has his pick of the big-name M What a beautiful drafted in her parent, brother and sake of my guests these days. But it’s testament to health voice Juliana fiancé to make it a family affair. his talents that even when his sofa isn’t possesses. It’s like Some people might find it chock-full of A-listers, he can make it a he did it first. He said, ‘I’m Nonetheless, Meghan certainly “I think that’s giving us anxiety honey oozing, spilling awkward to sing about needing very entertaining 50 minutes. enamoured with you’. I was like, thinks there is more to come in and I took a break from social gently over the twanging of guitar sweet love in the morning as your This week, he’s welcoming four-time ‘What does that mean? Just say it’.” terms of revelations in the music media for a minute and got back strings, all songbird softness and father offers backing vocals, but Oscar nominated actor Ethan Hawke. -

Dal 4 Gennaio Al Cinema

Presenta Diretto da BEN PALMER Con SIMON BIRD, JAMES BUCKLEY, BLAKE HARRISON Tratto dalla serie televisiva britannica di successo THE INBETWEENERS Durata 100 minuti I materiali sono scaricabili dall’area stampa di www.eaglepictures.com Pagina Facebook: facebook.com/FinalmenteMaggiorenni DAL 4 GENNAIO AL CINEMA Ufficio Stampa Eagle Pictures Marianna Giorgi [email protected] 1 NOTE DI PRODUZIONE Dal team della serie televisiva che ha battuto tutti i record, vincitrice di molti premi, arriva FINAMENTE MAGGIORENNI (The Inbetweeners Movie), la storia di quattro ragazzi che vanno in vacanza a Malia, Creta, senza genitori, senza professori, senza soldi e senza molto successo con le ragazze. La sceneggiatura è di Damon Beesley e Iain Morris, la regia di Ben Palmer, prodotto da Christopher Young. Il film sarà l’unico “outing” per ‘The Inbetweeners’ per il prossimo futuro. Gli Inbetweeners Simon Bird, James Buckley, Blake Harrison e Joe Thomas sono interpreti insieme agli attori fissi della serie televisiva, fra cui troviamo Emily Head come Carli, Belinda Stewart- Wilson come la mamma di Will e Greg Davies come il Signor Gilbert. Nel film debuttano Lydia Rose Bewley, Laura Haddock, Jessica Knappett e Tamla Kari. FINALMENTE MAGGIORENNI è prodotto dalla Bwark Productions e Young Films ed è finanziato da Channel 4, con Shane Allen come produttore esecutivo. Ci sono molte esperienze che segnano la vita dei teenager, dalla prima volta al pub alla molto gradita e incasinata prima vacanza senza i genitori. Finito l’anno scolastico alla Rudge Park Comprehensive, Will, Simon, Jay e Neil, cioé gli Inbetweeners, sono pronti per il mitico viaggio. -

HPS: Annual Report 2004-2005

Contents The Department Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 2 Staff and affiliates .......................................................................................................................... 3 Visitors and students ...................................................................................................................... 4 Comings and goings....................................................................................................................... 5 Roles and responsibilities .............................................................................................................. 6 Prizes, projects and honours........................................................................................................... 7 Seminars and special lectures ........................................................................................................ 8 Students Student statistics............................................................................................................................. 9 Part II primary sources essay titles .............................................................................................. 10 Part II dissertation titles ............................................................................................................... 13 MPhil essay and dissertation titles.............................................................................................. -

Televison Shot on Location in Haringey

Televison shot on location in Haringey Year Title Channel Starring Locations 2010 The Song of Lunch BBC Emma Thompson, Alan Rickman San Marco Restaurant (Tottenham) 2010 Imagine - Ray Davies BBC Ray Davies, Alan Yentob Hornsey Town Hall 2010 Waking The Dead IX BBC Trevor Eve, Sue Johnston Hornsey Coroners Court 2010 John Bishop's Britain BBC John Bishop Finsbury Park David Morrissey, Eddie Marsan 2010 Thorne: Scaredy Cat SKY 1 and Aidan Gillen, Sandra Oh Parkland Walk / Highgate Tunnels 2010 Chris Moyles Quiz Night Channel 4 Chris Moyles Coldfall Wood Nigel Slater's Simple 2010 Suppers BBC Nigel Slater Golf Course Allotments (Muswell Hill) 2010 Different Like Me BBC Park Road Lido & Gym Location, Location, 2010 Location Channel 4 Kirsty Allsop Crouch End Broadway 2010 Eastenders BBC The Decoreum, Wood Green 2010 The Trip BBC Steve Coogan, Rob Brydon Wood Vale 2010 The Gadget Show Channel 5 Suzi Perry Finsbury Park 2010 The Fixer (Series 2) ITV Andrew Buchan 21 View Road, Highgate Maxine Peake, Sophie Okonedo, Hornsey Town Hall (Crouch End), 2009 Criminal Justice (Series 2) BBC Mathew McFadyen Lightfoot Road Estate (Hornsey) 2009 Breaking The Mould BBC Dominic West Hornsey Town Hall Simon Bird, Joe Thomas, James 2009 The Inbetweeners Channel 4 Buckley, Blake Harrison Opera House Nightclub (Tottenham) Above Suspicion: The Red Last Stop Petrol Station, Stapleton Hall 2009 Dahlia ITV Kelly Reilly Road 2008 10 Days to War BBC Kenneth Branagh Hornsey Town Hall 2008 Moses Jones BBC Shaun Parkes. Matt Smith Hornsey Town Hall Who Do You Think -

Philosophy in Review/Comptes Rendus Philosophiques Academic

Philosophy in Review/Comptes rendus philosophiques Editor / Francophone associate editor / Directeur directeur adjoint francophone DavidKahane Alain Voizard Philosophy in Review Departement de philosophie Department of Philosophy Universite du Quebec a Montreal 4-115 Humanities Centre C.P. 8888, Succursale Centre-Ville University of Alberta Montreal, QC Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E5 Canada H3C 3P8 Tel: 780-492-8549 Fax: 780-492-9160 Courriel: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] An.glophone associate editors I directeurs adjoints anglophones Robert Burch Continental philosophy, history ofphilosoph y Glenn Griener Ethics, bioethics Cressida Heyes Feminism David Kahane Political, social, and legal philosophy Bernard Linsky Logic and philosophy of language Jeffrey Pelletier Cognitive science, philosophy ofmind Oliver Schulte Epistemology, philosophy ofscience Martin Tweedale Ancient and medieval philosophy, metaphysics Jennifer Welchman Ethics, bioethics, history ofphilosophy As a rule, P.I.R. publishes only invited reviews. However, we will consider for publication submitted reviews of new books in philosophy and related areas. Reviews must be a maximum of 1000 words and wilJ be accepted in either French or English. En general, C.R.P. ne publie que Jes coroptes rendus qui sont explicitement invitees. Neanmoins, nous prendrions en consideration la publication de coroptes rendus soumis, si les auteurs traitent de livres philosophiques (ou de livres sur un sujet apparente) qui viennent de paraitre. Les comptes rendus devraient -

STUDIOCANAL ACCELERATES ITS DEVELOPMENT in TV PRODUCTION Investments in Particularly Promising Companies in Spain and the UK

STUDIOCANAL ACCELERATES ITS DEVELOPMENT IN TV PRODUCTION Investments in particularly promising companies in Spain and the UK Cannes, April 4, 2016 – STUDIOCANAL is greatly accelerating its development in TV series production by announcing investments in several independent companies that are home to some of the most recognisable European talent in the industry. These investments concern Spanish company BAMBÚ PRODUCCIONES, a company based in Madrid of which STUDIOCANAL is acquiring 33%, URBAN MYTH FILMS in London (20%), and SUNNYMARCH TV also based in London (20%). Each deal includes distribution agreements. STUDIOCANAL already has a strong presence in TV series production via its subsidiaries TANDEM in Germany, and RED Production Company in the UK, as well as its stakes in SAM (Denmark) and GUILTY PARTY (UK). Founded in 2007 in Madrid, BAMBÚ PRODUCCIONES is run by its two founders, Teresa FernándeZ- Valdés and Ramon Campos. BAMBÚ stands out as one of the most creative TV production companies in Spain, with a slate of more than 10 original, high-quality, and internationally ambitious series. Among them, Refugiados, co-produced with BBC Worldwide, is the first Spanish series shot in English, while successful Grand Hotel and Velvet series have been sold all over the world. Based in London, URBAN MYTH FILMS was founded in 2013 by an experienced team of international producers and screenwriters. Johnny Capps and Julian Murphy were behind the launch of Shine Drama in 2002, and of several international hits series, including Merlin for BBC One. Howard Overman has created and written several hit shows, including Misfits on E4, which won a BAFTA in 2010. -

Jonny Sweet Writer/Performer

Jonny Sweet Writer/Performer Jonny is a talented actor, writer, performer and producer. His original comedy narrative series TOGETHER which he wrote and starred in and was produced by Cave Bear Productions and aired on BBC Three to critical acclaim. The series was derived from his successful BBC Radio 4 comedy HARD TO TELL which he also wrote and starred in and ran for two series. Agents Maureen Vincent Assistant Holly Haycock [email protected] 0203 214 0772 Credits Film Production Company Notes LITTLEHAMPTON StudioCanal Writer 2020 In Development Production Company Notes WOW CORPS Baby Cow 1 x 30 min script 2017 Radio Production Company Notes United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] SUNDAY AFTERNOON WITH TIM BBC KEY 2013 HARD TO TELL - Series Two Tiger Aspect Productions Writer & Star HARD TO TELL - Series One BBC Radio 4 / Tiger Aspect Writer and star of a 4 part radio series THE FULL MONTGOMERY BBC Sketch writer Television Production Company Notes GAP YEAR Eleven Films 1 x 45 min 2017 TOGETHER Tiger Aspect/ BBC Three 6 x 30min for BBC Three 2015 Writer, Associate Producer and Actor. Due to air in October 2015 CHICKENS CH4 COMEDY Big Talk / Channel 4 Writer of a 30' pilot with Simon Bird SHOWCASE and Joe Thomas 2011 CHICKENS SERIES Sky One / Big Talk 6 x 30' episodes 2013 Co-writer and star TOGETHER SERIES 1 Tiger Aspect Writer 2015 CHARLOTTE CHURCH Monkey Kingdom/Channel 4 Co-Presenter (himself) SHOW 1x30 Pilot BIG BROTHER'S BIG Channel