Winter 2020 Brooklyn Bird Club’S the Clapper Rail Winter 2020 Inside This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Family's Guide to Explore NYC for FREE with Your Cool Culture Pass

coolculture.org FAMILY2019-2020 GUIDE Your family’s guide to explore NYC for FREE with your Cool Culture Pass. Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org WELCOME TO COOL CULTURE! Whether you are a returning family or brand new to Cool Culture, we welcome you to a new year of family fun, cultural exploration and creativity. As the Executive Director of Cool Culture, I am excited to have your family become a part of ours. Founded in 1999, Cool Culture is a non-profit organization with a mission to amplify the voices of families and strengthen the power of historically marginalized communities through engagement with art and culture, both within cultural institutions and beyond. To that end, we have partnered with your child’s school to give your family FREE admission to almost 90 New York City museums, historic societies, gardens and zoos. As your child’s first teacher and advocate, we hope you find this guide useful in adding to the joy, community, and culture that are part of your family traditions! Candice Anderson Executive Director Cool Culture 2020 Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org HOW TO USE YOUR COOL CULTURE FAMILY PASS You + 4 = FREE Extras Are Extra Up to 5 people, including you, will be The Family Pass covers general admission. granted free admission with a Cool Culture You may need to pay extra fees for special Family Pass to approximately 90 museums, exhibits and activities. Please call the $ $ zoos and historic sites. museum if you’re unsure. $ More than 5 people total? Be prepared to It’s For Families pay additional admission fees. -

Prospect Park Zoo Free on Wednesday

Prospect park zoo free on wednesday oM Weekend Agenda: Free Admission in Brooklyn, Car-Free Queens, Craft Beer and Lobster Festivals, More. The Prospect Park Zoo, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Brooklyn Museum and more open their doors to the public for a day of free admission on Sunday. Chamber pop darlings Ra Ra Riot. A cheat sheet for free times and pay-what-you-wish days at day on Wednesdays at this amazing zoo—we're big fans of the World of Reptiles. Free admission for ages 19 and under. November through February, admission is free on weekdays. Read more. Prospect Park. WCS membership helps save wildlife and offers these great benefits: free admission all year to 5 WCS parks, free parking and faster park entry. Be sure to check the daily schedule of feedings and enrichment demonstrations happening at exhibits throughout the park. Parking is not available at the zoo itself; however, free parking is available on Flatbush Avenue. WCS does not honor reciprocal memberships from other zoos. Admission to Prospect Park Zoo is $8 for adults and $5 for kids ages On Wednesdays from 2pmpm, admission to the zoo is free for. Saturday- Sunday 11 am–4 pm. Free admission for children with paid adult admission. Prospect Park Zoo is sharing in the Park's celebration. The Bronx Zoo is open year-round. We close on the following holidays: Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day, New Year's Day, and Martin Luther King Day. Spring. The Central Park Zoo is open days a year, and the animals are on exhibit all year-round. -

EKOKIDS: SCHOOLYARD NATURE GUIDES Birds

EKOKIDS:SCHOOLYARD NATURE GUIDES Trees Mammals Invertebrates Reptiles & Birds Amphibians EKOKIDS: SCHOOLYARD NATURE GUIDES Birds Birds are common visitors to schools, neighborhoods, parks, and other public places. Their diversity, bright colors, cheerful songs, and daytime habits make them great for engaging children and adults in nature study. Birds are unique among animals. All birds have feathers, wings, and beaks. They are found around the world, from ice-covered Antarctica to steamy jungles, from dry deserts to windy mountaintops, and from freshwater rivers to salty oceans. This booklet shares some information on just a few of the nearly 10,000 bird species that can be found worldwide. How many of these birds can you find in your part of the planet? Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) DESCRIPTION • Other names: redbird, common cardinal • Medium-sized songbird in the cardinal family • Males: bright red feathers, black face masks • Females: light brown feathers, gray face masks • Males and females: reddish-orange bills • Length: 8¾ inches; wingspan: 12 inches HABITAT The northern cardinal can be found throughout the Birds eastern U.S. This native species favors open areas with brushy habitat, including neighborhoods and NORTHERN CARDINAL suburban areas. FUN FACT EKOKIDS: SCHOOLYARD NATURE GUIDES Northern cardinals mate for life. When courting, the Mississippi State University Extension Service male feeds the female beak-to-beak. H ouse Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) DESCRIPTION • Other name: rosefinch • Length: 6 inches; wingspan: 9½ inches • Males: bright, orange-red face and breast; streaky, gray-brown wings and tail • Females: overall gray-brown; no bright red color HABITAT The house finch is not native to the southeastern U.S. -

State of the Park Report, Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, Georgia

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior State of the Park Report Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park Georgia November 2013 National Park Service. 2013. State of the Park Report for Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park. State of the Park Series No. 8. National Park Service, Washington, D.C. On the cover: Civil War cannon and field of flags at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park. Disclaimer. This State of the Park report summarizes the current condition of park resources, visitor experience, and park infrastructure as assessed by a combination of available factual information and the expert opinion and professional judgment of park staff and subject matter experts. The internet version of this report provides the associated workshop summary report and additional details and sources of information about the findings summarized in the report, including references, accounts on the origin and quality of the data, and the methods and analytic approaches used in data collection and assessments of condition. This report provides evaluations of status and trends based on interpretation by NPS scientists and managers of both quantitative and non- quantitative assessments and observations. Future condition ratings may differ from findings in this report as new data and knowledge become available. The park superintendent approved the publication of this report. Executive Summary The mission of the National Park Service is to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of national parks for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. NPS Management Policies (2006) state that “The Service will also strive to ensure that park resources and values are passed on to future generations in a condition that is as good as, or better than, the conditions that exist today.” As part of the stewardship of national parks for the American people, the NPS has begun to develop State of the Park reports to assess the overall status and trends of each park’s resources. -

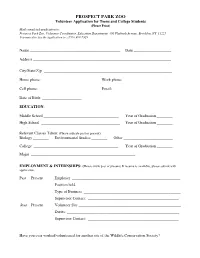

School Year Volunteering Please Check Which School Year Option You Are Applying For

PROSPECT PARK ZOO Volunteer Application for Teens and College Students (Please Print) Mail completed application to: Prospect Park Zoo, Volunteer Coordinator, Education Department, 450 Flatbush Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11225 You may also fax the application to: (718) 399-7329 Name ______________________________________________ Date ___________________ Address ______________________________________________________________________ City/State/Zip _________________________________________________________________ Home phone: _______________________ Work phone: ________________________ Cell phone: ________________________ Email: _____________________________ Date of Birth: ____________________ EDUCATION: Middle School ______________________________________ Year of Graduation ________ High School ________________________________________ Year of Graduation ________ Relevant Classes Taken: (Please indicate past or present) Biology ________ Environmental Studies ________ Other _________________________ College ___________________________________________ Year of Graduation ________ Major _____________________________________________________ EMPLOYMENT & INTERNSHIPS: (Please circle past or present) If resume is available, please submit with application. Past Present Employer _______________________________________________________ Position held ____________________________________________________ Type of Business _________________________________________________ Supervisor Contact: ______________________________________________ ✰ast Present Volunteer -

Alarm Calls of Tufted Titmice Convey Information About Predator Size and Threat Downloaded from Jason R

Behavioral Ecology doi:10.1093/beheco/arq086 Advance Access publication 27 June 2010 Alarm calls of tufted titmice convey information about predator size and threat Downloaded from Jason R. Courter and Gary Ritchison Department of Biological Sciences, Eastern Kentucky University, Moore 235, 521 Lancaster Ave., Richmond, KY 40475, USA Many birds utter alarm calls when they encounter predators, and previous work has revealed that variation in the characteristics http://beheco.oxfordjournals.org of the alarm, or ‘‘chick-a-dee,’’ calls of black-capped (Poecile atricapilla) and Carolina (P. carolinensis) chickadees conveys infor- mation about predator size and threat. Little is known, however, about possible information conveyed by the similar ‘‘chick-a-dee’’ alarm call of tufted titmice (Baeolophus bicolor). During the winters of 2008 and 2009, free-ranging flocks (N ¼ 8) of tufted titmice were presented with models of several species of raptors that varied in size, and titmice responses were monitored. Smaller, higher threat predators (e.g., eastern screech-owl, Megascops asio) elicited longer mobbing bouts and alarm calls with more notes (D-notes) than larger lower threat predators (e.g., red-tailed hawk, Buteo jamaicensis). During playback experiments, titmice took longer to return to feeding after playbacks of alarm calls given in response to a small owl than to playbacks given in response to a large hawk or a robin (control). Like chickadees, titmice appear to utter alarm calls that convey information about predator size and threat. Titmice, however, appear to cue in on the total number of D-notes given per unit time instead of the number of D-notes per alarm call. -

Grizzly Bears Arrive at Central Park Zoo Betty and Veronica, the fi Rst Residents of a New Grizzly Bear Exhibit at the Central Park Zoo

Members’ News The Official WCS Members’ Newsletter Mar/Apr 2015 Grizzly Bears Arrive at Central Park Zoo Betty and Veronica, the fi rst residents of a new grizzly bear exhibit at the Central Park Zoo. escued grizzly bears have found a new home at the Betty and Veronica were rescued separately in Mon- RCentral Park Zoo, in a completely remodeled hab- tana and Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. itat formerly occupied by the zoo’s polar bears. The Both had become too accustomed to humans and fi rst two grizzlies to move into the new exhibit, Betty were considered a danger to people by local authori- and Veronica, have been companions at WCS’s Bronx ties. Of the three bears that arrived in 2013, two are Zoo since 1995. siblings whose mother was illegally shot, and the third is an unrelated bear whose mother was euthanized by A Home for Bears wildlife offi cials after repeatedly foraging for food in a Society Conservation Wildlife © Maher Larsen Julie Photos: The WCS parks are currently home to nine rescued residential area. brown bears, all of whom share a common story: they “While we are saddened that the bears were or- had come into confl ict phaned, we are pleased WCS is able to provide a home with humans in for these beautiful animals that would not have been the wild. able to survive in the wild on their own,” said Director of WCS City Zoos Craig Piper. “We look forward to sharing their stories, which will certainly endear them in the hearts of New Yorkers. -

HHH Collections Management Database V8.0

HENRY HUDSON PARKWAY HAER NY-334 Extending 11.2 miles from West 72nd Street to Bronx-Westchester NY-334 border New York New York County New York WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD HENRY HUDSON PARKWAY HAER No. NY-334 LOCATION: The Henry Hudson Parkway extends from West 72nd Street in New York City, New York, 11.2 miles north to the beginning of the Saw Mill River Parkway at Westchester County, New York. The parkway runs along the Hudson River and links Manhattan and Bronx counties in New York City to the Hudson River Valley. DATES OF CONSTRUCTION: 1934-37 DESIGNERS: Henry Hudson Parkway Authority under direction of Robert Moses (Emil H. Praeger, Chief Engineer; Clinton F. Loyd, Chief of Architectural Design); New York City Department of Parks (William H. Latham, Park Engineer); New York State Department of Public Works (Joseph J. Darcy, District Engineer); New York Central System (J.W. Pfau, Chief Engineer) PRESENT OWNERS: New York State Department of Transportation; New York City Department of Transportation; New York City Department of Parks and Recreation; Metropolitan Transit Authority; Amtrak; New York Port Authority PRESENT USE: The Henry Hudson Parkway is part of New York Route 9A and is a linear park and multi-modal scenic transportation corridor. Route 9A is restricted to non-commercial vehicles. Commuters use the parkway as a scenic and efficient alternative to the city’s expressways and local streets. Visitors use it as a gateway to Manhattan, while city residents use it to access the Hudson River Valley, located on either side of the Hudson River. -

Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide INTRODUCTION . .2 1 CONEY ISLAND . .3 2 OCEAN PARKWAY . .11 3 PROSPECT PARK . .16 4 EASTERN PARKWAY . .22 5 HIGHLAND PARK/RIDGEWOOD RESERVOIR . .29 6 FOREST PARK . .36 7 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK . .42 8 KISSENA-CUNNINGHAM CORRIDOR . .54 9 ALLEY POND PARK TO FORT TOTTEN . .61 CONCLUSION . .70 GREENWAY SIGNAGE . .71 BIKE SHOPS . .73 2 The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway System ntroduction New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (Parks) works closely with The Brooklyn-Queens the Departments of Transportation Greenway (BQG) is a 40- and City Planning on the planning mile, continuous pedestrian and implementation of the City’s and cyclist route from Greenway Network. Parks has juris- Coney Island in Brooklyn to diction and maintains over 100 miles Fort Totten, on the Long of greenways for commuting and Island Sound, in Queens. recreational use, and continues to I plan, design, and construct additional The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway pro- greenway segments in each borough, vides an active and engaging way of utilizing City capital funds and a exploring these two lively and diverse number of federal transportation boroughs. The BQG presents the grants. cyclist or pedestrian with a wide range of amenities, cultural offerings, In 1987, the Neighborhood Open and urban experiences—linking 13 Space Coalition spearheaded the parks, two botanical gardens, the New concept of the Brooklyn-Queens York Aquarium, the Brooklyn Greenway, building on the work of Museum, the New York Hall of Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, Science, two environmental education and Robert Moses in their creations of centers, four lakes, and numerous the great parkways and parks of ethnic and historic neighborhoods. -

Impact Report We Stand for Wildlife® SAVING WILDLIFE MISSION

2020 Impact Report We Stand for Wildlife® SAVING WILDLIFE MISSION WCS saves wildlife and wild places worldwide through science, conservation action, education, and inspiring people to value nature. R P VISION E R V O O T WCS envisions a world where wildlife E C SAVING C thrives in healthy lands and seas, valued by S I WILDLIFE T societies that embrace and benefit from the D diversity and integrity of life on Earth. & WILD PLACES INSPIRE DISCOVER We use science to inform our strategy and measure the impact of our work. PROTECT We protect the most important natural strongholds on land and at sea, and reduce key threats to wildlife and wild places. INSPIRE We connect people to nature through our world- class zoos, the New York Aquarium, and our education and outreach programs. 2 WCS IMPACT REPORT 2020 “It has taken nature millions of years to produce the beautiful and CONTENTS wonderful varieties of animals which we are so rapidly exterminating… Let us hope this destruction can 03 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT/CEO AND CHAIR OF THE BOARD be checked by the spread of an 04 TIMELINE: 125 YEARS OF SAVING WILDLIFE AND WILD PLACES intelligent love of nature...” 11 CONSERVATION SCIENCE AND SOLUTIONS —WCS 1897 Annual Report 12 How Can We Prevent the Next Pandemic? 16 One World, One Health 18 Nature-Based Climate Solutions LETTER FROM THE 22 What Makes a Coral Reef Resilient? PRESIDENT/CEO AND CHAIR OF THE BOARD 25 SAVING WILDLIFE 26 Bringing Elephants Back from the Brink This year marks the 125th anniversary of the founding of expertise in wildlife health and wildlife trafficking, 28 Charting the Path for Big Cat Recovery the Wildlife Conservation Society in 1895. -

Birds in Urban Gardens

BIRDS IN URBAN GARDENS By Leo Shapiro Throughout history, birds have fascinated us. They are able to fly, as no human beings can do, and many of them are bright and colorful. Some birds are wonderful songsters, and their cheerful sounds add beauty and a note of victory to the air. They are an essential part of a garden’s ecology. They control insect populations and help to spread plants by eating berries and releasing the indigested seeds in their droppings. In the following resource sheet, various aspects of attracting birds to urban gardens and encouraging them to nest are discussed. A bibliography is also included for those who want to study birds further. Planting For Birds Birds use shrubs and trees year-round for food and, in summer, for nesting. The following plantings are excellent for attracting birds to the urban garden: Shrubs and Vines Fruiting Period American Elderberry, Sambucus canadensis Late Summer – mid-fall Amur Honeysuckle, Lonicera maakii Fall Arrowwood, Viburnum dentatum Fall Bayberry , Myrica pennslyvanica Fall to early spring Black Haw , Viburnum prunifolium Fall Highbush Blueberry , Vaccinium corymbosum Early summer - fall Nannyberry, Viburnum lentago Fall Siberian Dodwood, Cornus alba sibirica Fall Tartatian Honeysuckle , Lonicera tatarica Summer Sargent Crabapple, Malus sargentii Fall Winterberry, Ilex verticulata Fall-winter Blackberry and Raspberry, Rubus spp. Summer Red Osier Dogwood , Cornus stolonifera Midsummer - fall Japanese Barberry, Berberis thunbergii Fall-winter Chokecherry , Aronia arbutifolia Fall-winter Sumac, Rhus spp. Early summer - winter Serviceberry, Amelanchier spp. Early summer - fall Greenbrier, Smilax spp. Fall - winter Elderberry, Sambucus canadensis Late summer - fall Virginia Creeper, Parthenocissus quinquefolia Late summer - winter Bittersweet , Celastrus scandens Fall - winter Wild Rose, Rosa sp. -

Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus Bicolor) Gail A

Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor) Gail A. McPeek Kensington, MI 11/29/2008 © Joan Tisdale With a healthy appetite for sunflower seeds, (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) the Tufted Titmouse is a common feeder bird. In fact, many attribute our enthusiasm for Forty years later, Wood (1951) categorized the feeding birds as partly responsible for this Tufted Titmouse as a resident in the species’ noteworthy northward expansion. southernmost two to three tiers of counties, and Titmice can reside year-round in colder climates indicated it was “increasing in numbers and thanks to this convenient chain of fast-food spreading northward.” He noted winter records restaurants. Climate change and reforestation of as far north as Ogemaw and Charlevoix many areas have also played a role in its counties. Zimmerman and Van Tyne (1959) expansion (Grubb and Pravosudov 1994). The reported confirmed breeding records in Tufted Titmouse is found across eastern North Newaygo (1937) and Lapeer (1945) counties, America, west to the Plains and north to plus a family group seen 8 August 1945 in northern New England, southern Ontario, Benzie County. Michigan’s NLP, and central Wisconsin. The southern portion of its range extends across Breeding bird atlases have been timely in Texas and into eastern Mexico. In Texas, the documenting the continuing saga of the Tufted gray-crested form of the East meets with the Titmouse. By the end of MBBA I in 1988, it locally-distributed Black-crested Titmouse. inhabited most (83%) of SLP townships and one-quarter of NLP townships (Eastman 1991). Distribution These records provided a clear picture of this The slow and steady northward expansion of the species’ population increase and major Tufted Titmouse in Michigan is well northward expansion since the 1940s.