MIT CREW – Class of 1963 – 50Th Reunion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Here!

THE SPORT OF ROWING To the readers of www.row2k.com This spring the excerpts on The limited collector edition of my www.row2k.com have been concentrating on new book, The Sport of Rowing, from the early careers of two of recent American whence have come all these excerpts, sold rowing history’s most influential figures: out in April in about a week. Thanks so Harry Parker and Allen Rosenberg. This much to all of you who have showed such excerpt brings to a close the narrative of the faith in the book. 1960s and 1970s. It is a reminder that into The paperback standard edition re- every life a little rain must fall, and with mains on sale at: rowers involved, it can it can be a real gully- www.row2k.com/rowingmall/ washer. This edition has all the same content as The following .pdf is in the format in- the collector edition. The illustrations are in tended for the final printed book. The color black and white, and the price is much more you see will be duplicated in the limited col- affordable. lector edition. All these excerpts are from Both editions will be published in Octo- the third of the four volumes. ber. Incidentally, all the excerpts that have And remember, you can always email appeared on row2k during the last six me anytime at: months have since been revised as we work [email protected] toward publication. The most recent drafts are now posted in the row2k archives. Many thanks. THE SPORT OF ROWING 112. -

I ´Due´ John B. Kelly

La leggenda dei Kelly di Claudio Loreto z John Brendan Kelly, il “muratore” Lo statunitense John Brendan Kelly è stato il primo canottiere a collezionare tre medaglie d’oro olimpiche. Più che a tale primato, tuttavia, la sua fama – che andò decisamente al di là dell’ambito sportivo – è legata al mito americano del “self-made man”, da egli pienamente incarnato. Ultimo di dieci figli di emigrati irlandesi, John (detto anche Jack) nacque a Filadelfia il 4 ottobre 1889.1 Muratore, sviluppò una grande passione per lo sport; dopo qualche esperienza nel rugby, nella pallacanestro e nella pallanuoto, approdò al canottaggio, nel quale presto si affermò - per i colori del Vesper Boat Club di Filadelfia 2 - come il miglior “sculler” 3 degli Stati Uniti. La I Guerra Mondiale lo obbligò a sospendere la voga, arruolandolo nelle fila dell’esercito come soldato semplice. Durante la ferma in Francia Kelly prese parte - nella categoria “pesi massimi” - al torneo militare americano di pugilato, conseguendo dodici vittorie consecutive prima di essere bloccato da un infortunio. Il torneo sarebbe infine stato vinto da Gene Tunney, futuro campione del mondo professionista; in seguito Kelly avrebbe canzonato Tunney: “Non fosti fortunato, allorchè mi si ruppe una caviglia?”. Congedato al termine del conflitto con il grado di tenente, Kelly avviò a Filadelfia un’impresa edile che lo avrebbe poi reso miliardario; contemporaneamente riprese in mano i remi, ripristinando negli U.S.A. il proprio predominio nella specialità dello “skiff” 4. Nel 1920 avanzò richiesta di partecipazione alla “Diamond Sculls”, la prestigiosissima gara dei singolisti in seno alla “Henley Royal Regatta” (all’epoca la più importante manifestazione remiera annuale del mondo). -

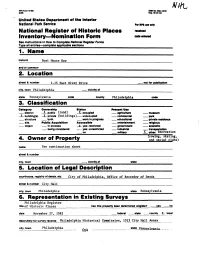

National Register of Historio Places Inventory—Nomination Form

MP8 Form 10-900 OMeMo.10M.0018 (342) Cup. tt-31-04 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historio Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Aeg/ster Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name historic Boat House Row and or common 2. Location street & number 1-15 East River Drive . not for publication city, town Philadelphia vicinity of state Pennsylvania code county Philadelphia code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use __district JL public (land) _X_ occupied _ agriculture _ museum _JL building(s) JL private (buildings)__ unoccupied —— commercial —— park __ structure __ both __ work in progress —— educational __ private residence __ site Public Acquisition Accesaible __ entertainment __ religious __ object __ in process _X- yes: restricted __ government __ scientific __ being considered _.. yes: unrestricted __ industrial —— transportation __no __ military JL. other: Recreation Trowing, skating, 4. Owner of Property and social clubs') name See continuation sheet street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. City of Philadelphia, Office of Recorder of Deeds street & number City Hall_____ _____________________________• city, town Philadelphia state Pennsylvania 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Philadelphia Register title of Historic Places yes no date November 27, 1983 federal state county JL local depository for survey records Philadelphia Historical Commission, 1313 City HaH Annex city, town Philadelphia _____.____ state Pennsylvania 65* 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent X deteriorated .. unaltered X original site good ruins X_ altered .moved date ...... -

Chapter 2 20Th Century

THE SPORT OF ROWING To the readers of www.row2k.com With this excerpt from The Sport of For our excerpts during the spring rac- Rowing, Two Centuries of Competition, we ing season, we are concentrating on the ca- return to www.row2k.com after a few weeks reers of two of recent American rowing his- off. tory’s most influential figures: Harry These have been very productive weeks Parker and Allen Rosenberg. These two for the book. We have recently announced have been bitter rivals since 1964, and there- that the publisher of our book is the River & in lies a tale. We begin with a short excerpt. Rowing Museum in Henley-on-Thames in England, and we have further announced The following .pdf is in the format in- that the limited collector edition will go on tended for the final printed book. The color sale to the public starting on Wednesday you see will be duplicated in the limited col- April 6, 2011, just two days from today, ex- lector edition. This excerpt is from the third clusively on the rowing mall of row2k.com. of the four volumes. There will be just 300 sets printed, and only 250 will ever be sold. Of those, nearly Incidentally, all the excerpts that have 200 have already been reserved, so I encour- appeared on row2k during the last six age anyone interested in purchasing one of months have since been revised as we work the remaining sets of the collector edition to steadily toward publication. The most re- visit the rowing mall early on April 6. -

Head of the Schuylkill Schuylkill River, Philadelphia, PA Oct 26, 2019 - Oct 27, 2019

Head of the Schuylkill Schuylkill River, Philadelphia, PA Oct 26, 2019 - Oct 27, 2019 Saturday 01B. Para Racing 1x Sat 8:00 Official Place Bow Name St. Joe's Tower Angels Raw +/- Adjusted 1 3 Andrew McLellan 03:39.3 09:13.8 15:28.0 20:01.2 20:01.2 (West Side Rowing Club) 2 2 Katherine Valdez 05:19.0 14:09.9 24:12.5 30:22.7 30:22.7 (Row New York) 01C. Adaptive/Inclusion 2x Sat 8:00 Revised Place Bow Name St. Joe's Tower Angels Raw +/- Adjusted 1 7 Philadelphia Adaptive Rowing PAR 03:33.9 09:04.8 15:09.8 19:02.6 Age: 38 -10.51 18:52.1 (Gallagher, H.) 2 5 Rockland Rowing Association, Inc. 03:51.3 09:42.8 16:13.4 20:24.9 Age: 59 -1:28.98 18:55.9 (Gold, R.) 3 9 Philadelphia Adaptive Rowing PAR 03:39.0 09:26.3 15:50.1 20:02.5 Age: 19 20:02.5 (Doughty, J.) 4 6 Row New York 03:54.9 09:59.5 16:57.7 21:16.8 Age: 21 21:16.8 (Choe, W.) 5 8 Philadelphia Adaptive Rowing PAR 04:35.6 11:51.7 19:34.3 24:19.3 Age: 67 -2:19.03 22:00.3 (Loudon, J.) 6 10 Philadelphia Adaptive Rowing PAR 04:51.9 12:35.0 21:11.7 26:45.3 Age: 15 26:45.3 (Chernets, W.) 02A. Mens Championship Pair w/out Cox Sat 8:30 Official Place Bow Name St. -

1970 Head of the Charles

The Head is coxswains race This one took his Eight through the wro was unable to turn his boat sharpi to get back on course 1970 Head Of The Charles by Robert Mekenna On crisp day in late October nearly one thousand oarsmen ing debut after rowing to fame with past Yale crews and oarswomen in more than 230 shells gathered on the In the Junior Lightweight Singles Event MIT fri Charles River in Boston to participate in the sixth annual John Sheetz came away with well deserved Head of The Charles Regatta This mammouth event brought field of 22 aspiring juniors Three oarswomi wide and varied representation of American and Canadian this event Gail Pierson flashed over the three rowing talent together for the final time in 1970 2205.6 beating Kathy Kalkhof of Philadelphia The uniqueness of the Head lies primarily in its three Becker of Vesper by nearly full minute mile test against the clock stretching over winding and The Junior Singles Sculls Louis Hawes Memorial challenging course Oarsmen and scullers alike are forced to Trophy was won by Dick Abromeit in 1942 eight socondc cope with tortuous course with constantly changing wind in front of Mount Hermons Charles Hamilton and Unionfs conditions Bill Miller who had represented the U.S.A in 1969 at The races started sharply at noon With almost windless Klagenfurt in pair conditions many of the course records were expected to Oarsmen and spectators eagerly awaited the outcome of fall and did in all thirteen events The finish of the first race the Senior Lightweight Singles event Great interest -

Official Program

Official Program 2019 USROWING NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS July 9-14, 2019 Two Can (Still) Play That Game HEALTH CARE FOR THE UNIVERSE OF YOU Our team needs you. Let the games begin (again) with comprehensive sports medicine and orthopedic care from the team at Mercy Health. To find a sports medicine or orthopedic doctor near you, visit mercy.com/ortho Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Table of Contents 14 Welcome from Clermont County, Ohio ..........................4 Welcome from Ohio Department of Natural Resources ............4 Welcome from USRowing .....................................5 USRowing & Harsha Lake: A Winning Combination ...............6 2018 National Championship Results .......................... 10 Map of East Fork State Park .................................. 12 Rowing 101 ................................................. 14 2019 National Championships – Order of Events ................ 18 Regional Map & Things To Do ................................. 20 10 STAFF Jeff Blom President Sarah Gleason Marketing and Communications Manager Joel Barnhill Rowing Events Director Margaret Bedilion Sales Manager Amanda Berger Digital Marketing Coordinator To our rowing athletes, coaches, officials, families and visitors: Tracey Derico On behalf of the Clermont County Convention and Visitors Bureau staff and board, we are Office Manager thrilled to welcome the USRowing National Championships to our beautiful county! Katie Bishop Rowing Operations Intern We are privileged to serve in a vibrant and family friendly destination with a host of exceptional outdoor recreational activities, local dining, retail and regional attractions. BOARD OF Please enjoy your visit and get out and discover all the great things that make Clermont County and the Cincinnati region such a wonderful place! DIRECTORS James A. Comodeca We would like to thank USRowing for selecting Harsha Lake at East Fork State Park to host Mary Eisnaugle the USRowing National Championships for 2019 through 2021. -

Avon Tables Badge Sale Plan DCA Says Shore

-^1110 fN ‘>!ybd AHliaSb ■?3Ab J.S dId 003 ■ail o iian d >^dwd Aanasw AS/T3/3T 9TT0 T SERVING THE SHORE COMMUNITIES FROM THE HF2ART OF OCEAN GROVE SINCE 1875 VOL CCXXI NO. 30 TOWNSHIP OF NEPTUNE THURSDAY, JULY 25,1996 USPS 402420 THIRTY-FIVE CENTS Avon Tables Badge Sale Plan DCA Says Shore By Bonnie Graham will table indefinitely for this “i was on Ocean Avenue with from throughout Monmouth Avon - A resolution was an year the proposal to sell the police from 10 o’clock in County were on hand to con nounced to the controversial badges to non-residents." He the morning until iate that duct the pedestrian and ve Easy Working proposal to allow for the sale added,"The beach revenue is night. Overall, the festival hicular traffic along Ocean OCEAN GROVE - year ago there was solid of sponsored seasonal pool 73 percent of budget so far." went pretty well, with over ^venue and throughout the Charles Richman, Assis concern over the closing of badges to non-residents at Mayor Jerry Hauselt thanked 50,000 in attendance. The area. tant Commissioner of the Marlboro Psychiatric Hospi the Monday,July 22 Mayor the residents of Avon for their hot day brought in a great A number of defective beach Department of Community tal and the impact this ac and Commissioner meeting. cooperation during the Sun deal of beach traffic in addi lights will be replaced later Affairs, addressed the Sat tion would have on those Commissioner William day, July 14 Greek Festival, tion to the festival attendees,” this week and a $60,000 urday meeting of the Ocean communities which housed Dioguardi stated, “As of to during which time, Ocean The Mayor mentioned that a grant for the restoration of Grove Home Owners Asso a sizeable population of day, we have made 98 per Avenue became a one-way meeting had been held yes Sylvan Lake has been re ciation to provide an update deinstitutionalized resi cent of the pool budget. -

Usrowing U23 World Championship Trials 2010 Full Race Results Place

USRowing U23 World Championship Trials 2010 Full Race Results #2 Mens 1x (BM1x) Heat 1 1->Final, 2..->Rep (09:15:00) Official Place Entry Lane Time 1 USR Development Camp - Atlanta Rowing Club A (David Judah) 3 07:09.0 2 Craftsbury Sculling Center B (John Hood) 2 07:09.2 - Union Boat Club A (Brian Wettach) 4 DNS #3 Mens 1x (BM1x) Heat 2 (09:22:00) Official Place Entry Lane Time 1 Potomac Boat Club A (Brendan Mcewan) 5 07:08.8 2 University of Virginia Rowing Association A (Matthew Miller) 3 07:16.9 3 Unaffiliated .. (Singen Elliott) 4 07:19.7 4 GMS Rowing Center A (Dave Cullmer) 2 07:38.2 #8 Mens Ltwt 1x (BLM1x) Heat 1 1->Final, 2..->Rep (09:29:00) Official Place Entry Lane Time 1 Craftsbury Sculling Center A (John Graves) 3 07:04.4 2 USR Development Camp - Atlanta Rowing Club A (Sean Gibel) 4 07:26.3 #9 Mens Ltwt 1x (BLM1x) Heat 2 (09:36:00) Official Place Entry Lane Time 1 GMS Rowing Center A (Mike Orzolek) 3 07:05.5 2 Lake Union Crew A (Michael Wales) 4 07:09.3 3 Vesper Boat Club A (Adam Neinstein) 2 07:26.4 #12 Mens Ltwt 2- (BLM2-) Heat 1 1->Final, 2..->Rep (09:43:00) Official Place Entry Lane Time 1 USRowing U23 Lightweight Camp MIT (Chandler Mahaney, Cameron Mcalpine) 2 06:53.1 2 USRowing U23 Lightweight Camp MIT (Patrick Cleveland, Nic Smith) 4 06:58.6 3 Penn A.C. -

2016 Information Guide

Record Book 2016 Information Guide 1 2017Record INFORMATION Book Table of Contents Quick Facts UNIVERSITY General Information ........................................2 Location: Pullman, Wash. Enrollment: 20,193 Schedule ...........................................................3 Founded: 1890 Conference: Pac-12 2016-17 Roster .................................................4 Colors: Crimson and Gray Nickname: Cougars Coaching Staff .............................................5-7 President: Kirk Schulz Athletics Director: Bill Moos Meet the 2016-17 Cougars .......................8-30 Sr. Associate Director/SWA: Anne McCoy Faculty Athletics Representative: Ken Casavant 2015-16 Results ........................................31-32 Athletic Dept. Phone: 509.335.0311 Home Course: Wawawai Landing/Snake River Championship History ..................................33 COACHING INFORMATION Honors and Awards ................................34-35 Head Coach: Jane LaRiviere, 15th season LaRiviere’s E-mail: [email protected] All-Time Letterwinners .................................36 office phone: 509-335-0309 Associate Head Coach: Josh Adam, Seventh season Adam’s E-mail: [email protected] office phone: 509-335-0340 Assistant/Novice Karl Huhta, Third season Huhta’s E-mail: [email protected] office phone: 509-335-0961 Assistant Coach: Liz England, First season England’s E-mail: [email protected] office phone: 509-335-0320 Rowing Address: PO Box 641602 Pullman, WA 99164-1602 Office Phone: 509.335.0331, Fax: 509.335.5197 ATHLETIC MEDIA RELATIONS Student -

Boathouse Row: Waves of Change in the Birthplace of American Rowing

Excerpt • Temple University Press ERNESTINE BAYER Women and Their Fight for the Right to Row Before Ernestine Bayer got it into her head that she had a perfect right to row; before she arm- twisted her competitive- rower husband in the 1930s to find a way to get on the river; before she and other strong- willed Phila- delphia women passed the baton, one to the next, in a decades- long campaign to upend the no- women- here culture of Boat house Row and American rowing; before all of that, a few— very few— women rowed for sport, and when they did, they were mostly regarded as spectacles. 3 In 1870, Lottie McAlice and Maggie Lew, two Pittsburgh 16- year- olds, raced each other for 1 ⁄8 miles on the Mononga- hela River in what was touted as the “first female regatta.” An estimated 8,000 to 12,000 onlookers crowded the shores to watch the oddity, including press from Chicago, Cincinnati, and New York. McAlice, the victor in just under 18 minutes 10 seconds, won a prize of a gold watch. On New York City’s East River that same year, five teenage girls wearing dresses competed in a three- mile race in heavy 17- foot workboats as spectators lined the banks “for a considerable distance,” with the water “fairly covered” with plea sure boats, barges, and steamships. Excerpt • Temple University Press “Ladies Boat” II Another sketch recorded in the Button’s social logbook shows a T- shirted Bachelors’ rower ferrying his elegantly dressed date. It is titled “Sans souci,” or “No worries.” Logbook, the Button, May 1884. -

Racetrak.Com 2009 Usrowing Club Nationals Held on 07/15-19/2009

RaceTrak.com 2009 USRowing Club Nationals held on 07/15-19/2009 http://www.racetrak.com/central/public/RaceResultsrep.asp?Regatt... --> advertisment Login Status: Not Logged In Home Races Learn More Regatta Log on Race Results Report Regatta: 2009 USRowing Club Nationals Provided by RaceTrak.com Number Event Description Lane Team Description Results Notes Womens Intermediate 2x-Heat 01 Fedemex- Boat A 47A (Picture)(Detail) *01 ( Age:19 ) 08:38:43 Race Time: 07/15/2009 09:42 AM *04 Vesper Boat Club- Boat A 08:38:52 *** Race_is_Official *** 05 USR Development Camp - MIT- Boat E 08:39:64 ( Age:20 ) 03 Wisconsin Womens USRowing 08:51:74 Development Camp- Boat B USR Development Camp - MIT- Boat G 06 ( Age:20 ) 09:00:17 USR Development Camp - Atlanta Rowing 02 Club- Boat A 09:17:22 Boats marked with * advance to SEMI 47B Womens Intermediate 2x-Heat 02 *02 USR Development Camp - MIT- Boat B 08:21:22 (Detail) ( Age:19 ) Race Time: 07/15/2009 09:49 AM *04 US-CanAmMex- Boat B 08:25:60 Quad City Rowing Association- Boat A *** Race_is_Official *** 01 ( Age:19 ) 08:35:40 USR Development Camp - MIT- Boat F 06 ( Age:19 ) 08:53:77 South Jersey Rowing Club- Boat B 05 ( Age:21 ) 08:56:26 Steel City Rowing Club- Boat A 03 ( Age:16 ) 09:15:68 Boats marked with * advance to SEMI 47C Womens Intermediate 2x-Heat 03 *05 USR Development Camp - MIT- Boat A 08:04:80 (Detail) ( Age:21 ) Bloomington USRowing Pre-Elite Camp- Race Time: 07/15/2009 09:56 AM *06 Boat A 08:06:42 ( Age:23 ) Philadelphia Girls Rowing Club- Boat A *** Race_is_Official *** 03 ( Age:26 ) 08:12:55 Penn A.C.