Matt Berninger on Patience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watch the National's Vibrant New 'Sleep Well Beast' Video

Blistein, Jon. “Watch the National’s Vibrant New ‘Sleep Well Beast’ Video,” Rolling Stone, December 14, 2017 Watch the National’s Vibrant New ‘Sleep Well Beast’ Video The National‘s new video for “Sleep Well Beast,” the title track off their Grammy-nominated album, is a densely layered collage of city buildings, outdoor landscapes and people. The frantic movement of the visuals provides a fitting complement to the song’s angular production. Casey Reas directed the video, with designer Luke Hayman and photographer Graham MacIndoe. In an interview with Billboard, National singer Matt Berninger explained how Reas put together the video using MacIndoe’s pictures. “If you pause at any time in the video, you see a number of different levels of information happening. He’s using a number of different algorithms and tools. It’s a combo of programming, tech and the strange ways you can make that organic. It’s just a bunch of stoner nerds who are into art and rock.” The National also announced they were launching a new festival, Homecoming, in association with MusicNOW. The two-day event will take place April 28th and 29th in the band’s hometown of Cincin- nati, Ohio. The National will curate the lineup, which will feature over 20 artists across two stages in Smale Riverfront Park, as well as other venues throughout the city. The National will perform during both night’s of the festival as well. Weekend passes go on sale December 15th via the festival’s web- site. The National released Sleep Well Beast in September. -

The Nationalnational a Bitter, Angry Record in a Lot of Spots

ISSUE #28 MMUSICMAG.COM ISSUE #28 MMUSICMAG.COM Q&A songs and make records together, definitely and closer and repeatedly, the different “Our voices will be mixed together in a weird in the shadows. dimensions of our songs reveal themselves. I way.” I wanted it to sound like what would get why people label us dark or brooding or be on the radio in the afterlife, and she got Why was it easier to write this time? depressing. It’s the most obvious thing when into that. Our voices are kind of distorted Alligator was the first record we released you first hear us because of the sound of my and mutated into some weird hybrid that was signed to a real label. We were voice or the instrumentation we’re using. And creation in that section. But it’s not like, desperate for people to notice us, and they when I’m writing I definitely like to wallow “Here’s Annie Clark in her starring cameo!” did. But we had a lot of anxiety about how in the dark stuff, but often it’s also very silly People prefer that way because they know to follow that up without painting ourselves observations about my own neuroses or they’re not just being used for their name; into a corner. We knew we wanted to make obsessions. A lot of our songs are about it’s because we respect their musicality, something that wasn’t like Alligator, but we death and the idea of existence, but in kind and they’re friends. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

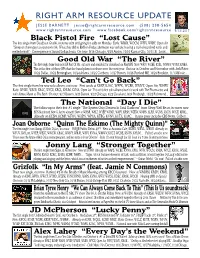

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 9/6/2017 Good Old War “The River” The first single from their new EP Part Of Me, out now The full EP is available for download on PlayMPE Early at KVNA This is the first of three EPs that the band plans to release over the next year On tour in October and November with Josh Ritter: 10/22 Dallas, 10/23 Birmingham, 10/24 Atlanta, 10/25 Carrboro, 10/27 Boston, 10/28 Portland ME, 10/29 Brooklyn, 11/1 Millvale... Ted Leo “Can’t Go Back” The first single from his new solo album, out this Friday, on PlayMPE now Early: WNKU, WBJB, KBAC, WYCE, KRCL, KHUM, KVNA, Open Air This is his first solo album since his work with The Pharmacists and with Aimee Mann as The Both On tour: 9/17 Boston, 9/20 Detroit, 9/22 Chicago, 9/23 Cleveland, 9/24 Pittsburgh, 10/23 Richmond, 10/24 Carrboro, 10/25 Atlanta... The National “Day I Die” The follow up to their first #1 single “The System Only Dreams In Total Darkness” from Sleep Well Beast, in stores Friday Most Added including KCSN, KCMP, WFUV, WXPN, WPYA, KTBG, KVNV, KUTX, KJAC, KVNA, WDST, WNKU, WVOD... Playing on Colbert this Thursday and featured on CBS This Morning Saturday this weekend US tour dates kick off in October Joan Osborne “Quinn The Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn)” The first single from Songs Of Bob Dylan, out now Most Added AGAIN! New this week at KRCC and WUTC Already on WFUV, XM Loft, WYEP, WEXT, WNCW, KBAC, WMVY, WBJB, WFIV, KVNA, WMWV, KOZT, WCBE, KMTN, KHUM.. -

RAGNAR KJARTANSSON & the NATIONAL a LOT of SORROW 27 JUNE – 23 AUGUST 2015 OPENING: 26 JUNE, 6-12 PM Here's What Happene

RAGNAR KJARTANSSON & THE NATIONAL A LOT OF SORROW 27 JUNE – 23 AUGUST 2015 OPENING: 26 JUNE, 6-12 PM Here’s what happened: You meet someone and play them your current favourite song, only to find out that it’s their favourite, too. Yes! Then you listen to it forever – or at least for six hours. If you don’t just have a weakness for pop music, but also for melancholy, and if you’re also a visual artist called Ragnar Kjartansson, then you might ask the band (in this case, The National), whether they would like to play the song (in this case, Sorrow) in New York’s MoMA PS1 non-stop for six consecutive hours – and then you make a film about the whole thing. This is the impact of these six hours: Exhaustion sets in, the song begins to change under the weight of time and the musicians begin to experiment cautiously. There are clashes and friction between pathos and irony, trance-like states set in and break off, until a new, collective experience between emotion and reflection, of presence and duration becomes possible. And if you prefer, you could also simply hear and see a literally wonderful concert. On view downstairs, under the repeated rhythms of Sorrow, Kjartansson’s most recent series of paintings is on show. Die Nacht der Hochzeit, watercolours of dark starry skies, and A Lot of Sorrow are both comprised of ever varying repetitions of the same subject. Painting and drawing is an essential part of Kjartansson’s practice, despite being best known for his large scale durational performances and video works. -

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 9/13/2017 Black Pistol Fire “Lost Cause” The first single from Deadbeat Graffiti, in stores 9/29 and going for adds on Monday Early: WBJB, WOCM, WFIV, WXRY, Open Air “Sleep on these guys at your own risk. What they did to BMI on Friday afternoon was unholy, leaving a trail of scorched earth and melted minds” - Consequence of Sound/Lollapalooza On tour: 9/16 Chicago, 9/29 Austin, 10/10 Kansas City, 10/11 St. Louis... Good Old War “The River” The first single from their new EP Part Of Me, out now and available for download on PlayMPE New: WFIV, WCBE, KYSL, WMWV, WUKY, KNBA... This is the first of three EPs that the band plans to release over the next year On tour in October and November with Josh Ritter: 10/22 Dallas, 10/23 Birmingham, 10/24 Atlanta, 10/25 Carrboro, 10/27 Boston, 10/28 Portland ME, 10/29 Brooklyn, 11/1 Millvale... Ted Leo “Can’t Go Back” The first single from his new solo album, out now First week at KEXP, KJAC, WFPK, WCBE, WMVY, Open Air, WHRV Early: WNKU, WBJB, KBAC, WYCE, KRCL, KHUM, KVNA, Open Air This is his first solo album since his work with The Pharmacists and with Aimee Mann as The Both On tour: 9/17 Boston, 9/20 Detroit, 9/22 Chicago, 9/23 Cleveland, 9/24 Pittsburgh, 10/23 Richmond... The National “Day I Die” The follow up to their first #1 single “The System Only Dreams In Total Darkness” from Sleep Well Beast, in stores now BDS Monitored New & Active already! New at WRNR, WRLT, WYEP, WTMD, WAPS, KRSH, WZEW, WNRN, KLRR, WCNR, KMTN, WYCE, KRML.. -

PH Mistaken for Strangers POLY

On tour with THE NATIONAL Pre ssehef t Synopsis Matt Berninger ist Leadsänger der schwer er- zwar eine wunderbare Rotzigkeit ein. Doch er folgreichen Indie-Rockband THE NATIONAL: verliert sein eigentliches Vorhaben bald aus berühmt, begehrt und verdammt angesagt. Sein dem Blick, feiert die Nächte durch, versinkt im Bruder Tom ist Amateur-Horrorfilmer, findet Chaos – und geht der Band gehörig auf die Ner- ven. Indie-Rock eine ziemliche Angeberei und würde in Schließlich wird Tom gefeuert und muss jedem Fall Heavy Metal vorziehen. Doch be- versuchen, aus dem Durcheinander der letzten geistert sind beide von der Idee, Tom könne die Monate so etwas wie einen Film zu machen. HIGH VIOLET Tour von THE NATIONAL beglei- ten MISTAKEN FOR STRANGERS über die Band THE und einen abgefahrenen Dokumentarfilm über NATIONAL ist eine filmische Ausnahmeer- die Band drehen. Eine Gelegenheit für die Brüder, scheinung, die viel Humor und noch mehr Stur- sich mit ihrer Kreativität und ihren Am- bitionen heit im selben Tourbus zusammenzwingt. Ein gegenseitig zu inspirieren. Wenn da nicht Toms vergnügtes, radikales Porträt über ungleiche gepflegter Chaotismus wäre und das schleichende Brüder, über fatale Ambitionen und über eine Gefühl, trotz Splatter-Ästhetik ir- gendwie im der aufregendsten Indie-Rockbands der Stun- de. Schatten des Bruders zu stehen. In das kühle Understatement der Band führt Tom The National THE NATIONAL rockt – die Band aus Cincinnati, Songs wie BLOODBUZZ OHIO und TERRIBLE Ohio, gehört zu den aufregendsten Musikacts LOVE wurde mehr als 600.000 Mal verkauft der Stunde. Nach fünf immer erfolgreicher und machte THE NATIONAL weltweit bekannt. Ein veröffentlichten Alben wurde ihre Platte Meilenstein der Bandgeschichte wurde die TROUBLE WILL FIND ME 2014 als Best fast zweijährige HIGH VIOLET Tour, eine Alternative Music Album für die Grammys ausverkaufte Show folgte der nächsten. -

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 9/9/2015 Darlingside Collective Soul Greg Holden “Go Back” “AYTA (Are You The Answer)” “Boys In The Street” The first single from Birds Say, in stores 9/18 The first single from See What You Started By Con- The powerful second single from Chase The Sun Headlining now, with Patty Griffin after 10/7 tinuing, their Vanguard debut, in stores October 2 Added early at WXPN, KCMP, WFUV, KVNA, WNKU... Early: WRSI, WFIV, WNTI, KSMF, KDEC, MPR, KFMG Early: WXRV, KCSN, WAPS, WFIV, KLRR, WOCM, Extensive tour with Vintage Trouble kicks off 9/12 “Darlingside are doing something new in pop KVNA, KDBB This is the band’s 21st year together “I have a lot of gay friends and I know a lot of music, which is kind of astonishing this late and their ninth album overall Hitting the road this people who have been through the struggle of in the game (ground the Beach Boys, Bea- fall: 9/29 Lake Buena Vista FL, 9/30 Clearwater FL, their family not understanding them. The song tles, Joni Mitchell, Pink Floyd, David Bowie, 10/1 Ft. Lauderdale FL, 10/3 Atlanta GA, 10/4 Lou- isn’t necessarily just supposed to be about a gay Talking Heads, Prince, Phish and Radiohead isville KY, 10/6 Columbia SC, 10/7 Raleigh NC, 10/9 kid and his dad. That song is a really a song of didn’t cover is hard to find).” - Boston Herald Charlotte NC, 10/10 Greensboro NC, 10/13 DC.. -

07/31/2017 Daily Program Listing II 06/14/2017 Page 1 of 123

Daily Program Listing II 43.1 Date: 06/14/2017 07/01/2017 - 07/31/2017 Page 1 of 123 Sat, Jul 01, 2017 Title Start Subtitle Distrib Stereo Cap AS2 Episode 00:00:01 NHK Newsline APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #8065 00:30:00 Global 3000 WNVC (S) (CC) N/A #925H Helping Islamic State Terror Group Victims In Iraq Thousands of women and children have been kidnapped and mistreated the so-called Islamic State terror group. A German psychotherapist is trying to help the victims. And fishermen in the Philippines are fighting to preserve dwindling fish stocks. 01:00:00 Song of the Mountains NETA (S) (CC) N/A #1120H Five Mile Mountain Road/Idle Time 02:00:00 Woodsongs NETA (S) (CC) N/A #1801H Jewel Jewel is a multi-platinum singer-songwriter, poet and actress. She has sold more than 25 million albums over her musical career. Her debut album Pieces of You had the hit "Who Will Save Your Soul". From the remote tundra of her Alaskan youth to the triumph of international stardom, the 41-year-old singer has always found a way to persevere and convey the emotional turmoil of life during it's most difficult and challenging moments through her work. Jewel tells the countless moments of introspection that led her here with her memoir Never Broken and new album Picking Up The Pieces. 03:00:00 Film School Shorts NETA (S) (CC) N/A #402H America '80s-inspired comedy Total Freak tells the story of how a boy's pursuit of his first summer camp kiss awakens a monster from the deep. -

Serpentine Prison, De Matt Berninger L Es Un Disco Que Merece Estar En El Catálogo De Quienes Aprecian El Rock Luminoso Y a La Vez Melancólico

NUESTRO MUNDO Ismael Lares // Twitter: @ismael_lares Serpentine Prison, de Matt Berninger l Es un disco que merece estar en el catálogo de quienes aprecian el rock luminoso y a la vez melancólico. os décadas como líder de la banda The National no por lo menos, una decena de músicos. A manera de agrade- Dbastan. Tampoco es suficiente haber colaborado cimiento, Matt publicó en su cuenta de Instagram un breve con Phoebe Bridgers en el melódico tema Walking On video en el que aparecen esos colaboradores, y en la barra A String; ni siquiera sobra que lo llamen rey de la música de comentarios remata que si uno quiere ser solista, nece- melancólica. Con asombrosa calma, en el nuevo álbum sitará a dichas personas. Esta demostración de agradeci- de Matt Berninger convergen dos identidades decisivas miento público y reconocimiento a quienes intercambian para las 10 canciones que conforman Serpentine Prison su arte con él ocurre a lo largo de su carrera. (Concord Records, 2020). Lo que quiero decir es que la relación creativa entre sus Pienso, por un lado, en la identidad de Berninger proyectos aporta mucho a este Berninger solista. Serpenti- como promotor musical, artístico y creador; por el otro, ne Prison posibilita la continuidad artística, al contrario de en el papel que ha desempeñado frente a The National, lo que ocurre por ejemplo con otras bandas o cantautores: la sobre todo como letrista. Pienso en Berninger como ar- colaboración se convierte en el núcleo del proyecto. tista en toma de conciencia, y en sus temas como parte de En cuanto a letras y música escribe sobre sí mismo: un repertorio que aspira a su propio arte. -

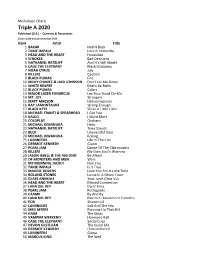

Triple a 2020

Mediabase Charts Triple A 2020 Published (U.S.) -- Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 Rank Artist Title 1 BAKAR Hell N Back 2 TAME IMPALA Lost In Yesterday 3 HEAD AND THE HEART Honeybee 4 STROKES Bad Decisions 5 NATHANIEL RATELIFF And It's Still Alright 6 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Black Madonna 7 NOAH CYRUS July 8 KILLERS Caution 9 BLACK PUMAS Fire 10 MILKY CHANCE & JACK JOHNSON Don't Let Me Down 11 WHITE REAPER Might Be Right 12 BLACK PUMAS Colors 13 MAJOR LAZER F/MARCUS Lay Your Head On Me 14 MT. JOY Strangers 15 MATT MAESON Hallucinogenics 16 RAY LAMONTAGNE Strong Enough 17 BLACK KEYS Shine A Little Light 18 MICHAEL FRANTI & SPEARHEAD I Got You 19 KALEO I Want More 20 COLDPLAY Orphans 21 MICHAEL KIWANUKA Hero 22 NATHANIEL RATELIFF Time Stands 23 BECK Uneventful Days 24 MICHAEL KIWANUKA Rolling 25 LUMINEERS Life In The City 26 DERMOT KENNEDY Giants 27 PEARL JAM Dance Of The Clairvoyants 28 KILLERS My Own Soul's Warning 29 JASON ISBELL & THE 400 UNIT Be Afraid 30 OF MONSTERS AND MEN Wars 31 MY MORNING JACKET Feel You 32 TAME IMPALA Is It True 33 MAGGIE ROGERS Love You For A Long Time 34 ROLLING STONES Living In A Ghost Town 35 GLASS ANIMALS Your Love (Deja Vu) 36 HEAD AND THE HEART Missed Connection 37 LANA DEL REY Doin' Time 38 PEARL JAM Retrograde 39 CAAMP By And By 40 LANA DEL REY Mariners Apartment Complex 41 EOB Shangri-LA 42 LUMINEERS Salt And The Sea 43 MEG MYERS Running Up That Hill 44 HAIM The Steps 45 VAMPIRE WEEKEND Harmony Hall 46 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Social Cues 47 DEVON GILFILLIAN The Good Life 48 DERMOT KENNEDY -

Pop: Latitude at Henham Park, Suffolk

FIRST NIGHT REVIEW Pop: Latitude at Henham Park, Suffolk The start of summer sent one of the best-booked bills of festival season, including Squeeze, Grimes and the National, soaring Lisa Verrico July 19 2016, 12:01am, The Times ★★★★☆ Latitude lacked its usual talking point — the surprise guests and secret shows that have become its calling card. Florence Welch made an unscheduled appearance on Friday to introduce a short film and local hero Ed Sheeran sneaked in on Sunday to duet with his friend Foy Vance, but both were low-key. Instead, the surprise was the start of summer, that special guest that Glastonbury couldn’t get. Much less buggy-jammed than it once was and with one of the best-booked bills of festival season, Latitude of late has had a high feel-good factor. This year, the weather sent it soaring. Christine and the Queens were the inevitable stars before dark on Friday, if partly because their billing was based on when they were booked — ie before the French superstar and her dancers stormed the UK charts. Just getting into the tent was an event; those who succeeded were still boasting about it by Sunday. Night-time pitted the Canadian dance genius Grimes against south London rockers the Maccabees. The former’s fierce performance caused such chaos that she had to plead with the crowd to calm down, surely a first for Latitude. The latter came with confetti cannons, surely a first for their fans. Squeeze were Saturday daytime’s generational bridge-builders, and despite their recent revival showed no signs of complacency.