Report for the EDMONTON JUDICIAL DISTRICT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 7: JRP SIR 69A Cultural Effects Review

October 2013 SHELL CANADA ENERGY Appendix 7: JRP SIR 69a Cultural Effects Review Submitted to: Shell Canada Energy Project Number: 13-1346-0001 REPORT APPENDIX 7: JRP SIR 69a CULTURAL EFFECTS REVIEW Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Report Structure .................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Overview of Findings ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Shell’s Approach to Community Engagement ..................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Shell’s Support for Cultural Initiatives .................................................................................................................. 7 1.6 Key Terms ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.6.1 Traditional Knowledge .................................................................................................................................... 9 1.6.2 Traditional -

Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. ISBN 978-0-7785-9870-7 PRINT ISBN 978-0-7785-9871-8 WEB ISSN 1925-5195 PRINT ISSN 1925-5209 WEB Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background. -

Traditional Knowledge Overview for the Athabasca River Watershed ______

Traditional Knowledge Overview for the Athabasca River Watershed __________________________________________ Contributed to the Athabasca Watershed Council State of the Watershed Phase 1 Report May 2011 Brenda Parlee, University of Alberta The Peace Athabasca Delta ‐ www.specialplaces.ca Table of Contents Introduction 2 Methods 3 Traditional Knowledge Indicators of Ecosystem Health 8 Background and Area 9 Aboriginal Peoples of the Athabasca River Watershed 18 The Athabasca River Watershed 20 Livelihood Indicators 27 Traditional Foods 30 Resource Development in the Athabasca River Watershed 31 Introduction 31 Resource Development in the Upper Athabasca River Watershed 33 Resource Development in the Middle Athabasca River Watershed 36 Resource Development in the Lower Athabasca River Watershed 37 Conclusion 50 Tables Table 1 – Criteria for Identifying/ Interpreting Sources of Traditional Knowledge 6 Table 2 – Examples of Community‐Based Indicators related to Contaminants 13 Table 3 – Cree Terminology for Rivers (Example from northern Quebec) 20 Table 4 – Traditional Knowledge Indicators for Fish Health 24 Table 5 – Chipewyan Terminology for “Fish Parts” 25 Table 6 – Indicators of Ecological Change in the Lesser Slave Lake Region 38 Table 7 – Indicators of Ecological Change in the Lower Athabasca 41 Table 9 – Methods for Documenting Traditional Knowledge 51 Figures Figure 1 – Map of the Athabasca River Watershed 13 Figure 2 – First Nations of British Columbia 14 Figure 3 – Athabasca River Watershed – Treaty 8 and Treaty 6 16 Figure 4 – Lake Athabasca in Northern Saskatchewan 16 Figure 5 – Historical Settlements of Alberta 28 Figure 6 – Factors Influencing Consumption of Traditional Food 30 Figure 7 – Samson Beaver (Photo) 34 Figure 8 – Hydro=Electric Development – W.A.C Bennett Dam 39 Figure 9 – Map of Oil Sands Region 40 i Summary Points This overview document was produced for the Athabasca Watershed Council as a component of the Phase 1 (Information Gathering) study for its initial State of the Watershed report. -

Athabasca Tribal Council

ATHABASCA TRIBAL COUNCIL UPGRADING AND POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION FUNDING POLICY Revised: April 1, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Definitions .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 3. Eligibility ................................................................................................................................................. 5 4. Application .............................................................................................................................................. 9 5. Types of Students ................................................................................................................................. 10 6. Full Time Student Supports .................................................................................................................. 11 7. Part Time Student Supports ................................................................................................................. 13 8. Consequences of Withdrawal............................................................................................................... 13 9. Funding Suspension .............................................................................................................................. 14 10. Frauds .................................................................................................................................................. -

Mikisew Cree First Nation

MIKISEW CREE FIRST NATION mikisewcree.ca OPPORTUNITY PROFILE │ Chief Financial Officer ABOUT MIKISEW CREE FIRST NATION Mikisew Cree First Nation signed Treaty 8 in 1899. The Mikisew Cree have resided in Northeastern Alberta since time immemorial. The Peace-Athabasca Delta, which is in the centre of their traditional lands, is a unique international ecosystem which is cherished. It is the source of much that sustains them. When the fur trade came west and established a trading fort in this area, the Mikisew Cree were among those who traded furs. The traditional lands of the Mikisew Cree First Nation range over much of the area where the Athabasca Oil Sands deposits have been found. Mikisew Cree First Nation shares this territory with four other First Nations that make up the Athabasca Tribal Council. At the present time, most Mikisew Cree First Nation members reside in Fort McMurray, Edmonton, Fort Smith, NWT and Fort Chipewyan. Their Nation has the largest population of the five Athabasca Tribal Council Nations. In 1986, a Treaty Land Entitlement was signed with Canada that created several Reserves in and around the Fort Chipewyan area and into the area north of Lake Athabasca. The Mikisew Cree First Nation is proud of their heritage, and confident in its bright future. THE OPPORTUNITY Accountable to the Chief Executive Officer, the Chief Financial Officer participates as an integral member of the senior management team and performs duties in accordance with the mandate and priorities of the Mikisew Cree First Nation Administration. The Chief Financial Officer will coordinate, administer, and supervise the day-to-day financial activities of the organization. -

CHILDREN's SERVICES DELIVERY REGIONS and INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES

CHILDREN'S SERVICES DELIVERY REGIONS and INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES DELEGATED FIRST NATION AGENCIES (DFNA) 196G Bistcho 196A 196D Lake 225 North Peace Tribal Council . NPTC 196C 196B 196 96F Little Red River Cree Nation Mamawi Awasis Society . LRRCN WOOD 1 21 223 KTC Child & Family Services . KTC 3 196E 224 214 196H Whitefish Lake First Nation #459 196I Child and Family Services Society . WLCFS BUFFALO Athabasca Tribal Council . ATC Bigstone Cree First Nation Child & Family Services Society . BIGSTONE 222 Lesser Slave Lake Indian Regional Council . LSLIRC 212 a Western Cree Tribal Council 221 e c k s a a 211 L b Child, Youth & Family Enhancement Agency . WCTC a NATIONAL th Saddle Lake Wah-Koh-To-Win Society . SADDLE LAKE 220 A 219 Mamowe Opikihawasowin Tribal Chiefs 210 Lake 218 201B Child & Family (West) Society . MOTCCF WEST 209 LRRCN Claire 201A 163B Tribal Chief HIGH LEVEL 164 215 201 Child & Family Services (East) Society . TCCF EAST 163A 201C NPTC 162 217 201D Akamkisipatinaw Ohpikihawasowin Association . AKO 207 164A 163 PARK 201E Asikiw Mostos O'pikinawasiwin Society 173B (Louis Bull Tribe) . AMOS Kasohkowew Child & Wellness Society (2012) . KCWS 201F Stoney Nakoda Child & Family Services Society . STONEY 173A 201G Siksika Family Services Corp. SFSC 173 Tsuu T'ina Nation Child & Family Services Society . TTCFS PADDLE Piikani Child & Family Services Society . PIIKANI PRAIRIE 173C Blood Tribe Child Protection Corp. BTCP MÉTIS SMT. 174A FIRST NATION RESERVE(S) 174B 174C Alexander First Nation . 134, 134A-B TREATY 8 (1899) Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation . 133, 232-234 174D 174 Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation . 201, 201A-G Bearspaw First Nation (Stoney) . -

Western Weekly Reports

WESTERN WEEKLY REPORTS Reports of Cases Decided in the Courts of Western Canada and Certain Decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada 2011-VOLUME 1 (Cited [2011] 1 W.W.R.) All cases of value from the courts of Western Canada and appeals therefrom to the Supreme Court of Canada SELECTION EDITOR Walter J. Watson, B.A., LL.B. ASSOCIATE EDITORS (Alberta) E. Mirth, Q.C. (British Columbia) Darrell E. Burns, LL.B., LL.M. (Manitoba) E. Arthur Braid, Q.C. (Saskatchewan) G.L. Gerrand, Q.C. CARSWELL EDITORIAL STAFF Jeffrey D. Mitchell, B.A., M.A. Director, Information Management and Manufacturing Michael Silverstein, M.A., LL.B. Product Development Manager Sharon Yale, LL.B., M.A. Supervisor, Legal Writing Julia Fischer, B.A.(HON.), LL.B. Acting Supervisor, Legal Writing Michel Marison, B.A.(HON.) Content Editor WESTERN WEEKLY REPORTS is published 48 times per year. Subscrip- Western Weekly Reports est publi´e 48 fois par ann´ee. L’abonnement est de tion rate $361.00 per bound volume including parts. Indexed: Carswell’s In- 361 $ par volume reli´e incluant les fascicules. Indexation: Index a` la docu- dex to Canadian Legal Literature. mentation juridique au Canada de Carswell. Editorial Offices are also located at the following address: 430 rue St. Pierre, Le bureau de la r´edaction est situ´e a` Montr´eal — 430, rue St. Pierre, Mon- Montr´eal, Qu´ebec, H2Y 2M5. tr´eal, Qu´ebec, H2Y 2M5. ________ ________ © 2011 Thomson Reuters Canada Limited © 2011 Thomson Reuters Canada Limit´ee NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER: All rights reserved. -

Appendix 139C.1 Frontier Oil Sands Mine Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan

Frontier Oil Sands Mine Project ESRD and CEAA Responses Integrated Application Appendix 139c.1: Frontier Oil Sands Mine Project Supplemental Information Request, Round 2 Aboriginal Consultation Plan Appendix 139c.1 Frontier Oil Sands Mine Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan October 2013 ESRD and CEAA Responses Frontier Oil Sands Mine Project Appendix 139c.1: Frontier Oil Sands Mine Project Integrated Application Aboriginal Consultation Plan Supplemental Information Request, Round 2 October 2013 UTS Energy Corporation & Teck Cominco Limited Frontier Oil Sands Mine Project A BORIGINAL C ONSULTATION P LAN UTS Energy Corporation (UTS) and Teck Cominco Limited (Teck Cominco) are committed to ensuring appropriate consultation with potentially affected Aboriginal communities with respect to the application of the Frontier Oil Sands Mine Project (the Project). The Aboriginal consultation process is designed to be ongoing from initial planning through construction, operations, and decommissioning of the proposed Project. UTS & Teck Cominco have developed this consultation plan for a number of reasons. The Crown has determined that the Project triggers consultation. Therefore, the Alberta’s First Nation Consultation Guidelines on Land Management and Resource Development requirements must be met. The Project has the potential to impact areas traditionally used by Aboriginal communities for hunting, trapping, fishing, gathering and other culturally significant activities. Finally, UTS & Teck Cominco recognizes that several Aboriginal communities may be affected by the proposed Project and intends to develop long‐lasting and mutually beneficial relationships with those communities. Project Description The proposed Frontier Project consists of a mining and bitumen extraction and processing facility to be developed in phases. Phase 1 is currently planned to be located on UTS and Teck Cominco’s jointly owned Leases 311, 468, 470, 477 and 610 on the west side of the Athabasca River in Townships 010 and 101 Range 11. -

Rebuilding Resilient Indigenous Communities in the RMWB: Final Report

Rebuilding Resilient Indigenous Communities in the RMWB: Final Report 1. Rebuilding Resilient Indigenous Communities in the RMWB Executive Report Timothy David Clark April 2018 Timothy David Clark October 2018 “We were on our own.” “This wound is still very, very raw. We’re not healed.” “That's what's bothering me right now: it's just like, I give up. I'm scared again. I've got no drive anymore. I didn't give up but I'm at that point where I don't care anymore.” “It was totally devastating. I just remember going by the house, the old homestead. And I cried, because it was gone. We were brought up there, raised there, the whole family. And the things that you lose, from parent's stuff and that, it’s all gone. It don't matter if you lose all your furniture. That can be replaced. But this stuff will never be replaced.” “If you ever fly over this fire, or for those of us that have that opportunity, you can see it, just like a dragon’s breath. When that dragon comes back again he's still got lots to burn, and if we're not ready we're gonna go this time. We got lucky last time. That’s what we did: we got lucky.” “Coming back to see the disaster, my hometown, we drove around and everything was ashes. I don't know, it's hard to explain how you felt in your mind, your heart, your soul. Everything was gone. But the whole thing is, I had some trees. -

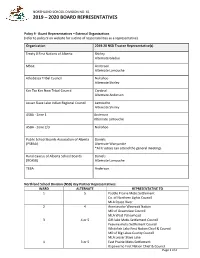

2019 – 2020 Board Representatives

NORTHLAND SCHOOL DIVISION NO. 61 2019 – 2020 BOARD REPRESENTATIVES Policy 9 - Board Representatives – External Organizations (refer to policy 9 on website for outline of responsibilities as a representative) Organization 2019-20 NSD Trustee Representative(s) Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta Shirley Alternate Gladue MSGC Anderson Alternate Lamouche Athabasca Tribal Council Nokohoo Alternate Shirley Kee Tas Kee Now Tribal Council Cardinal Alternate Anderson Lesser Slave Lake Indian Regional Council Lamouche Alternate Shirley ASBA - Zone 1 Anderson Alternate Lamouche ASBA - Zone 2/3 Nokohoo Public School Boards Association of Alberta Daniels (PSBAA) Alternate Wanyandie *All trustees can attend the general meetings Rural Caucus of Alberta School Boards Daniels (RCASB) Alternate Lamouche TEBA Anderson Northland School Division (NSD) Key Partner Representatives: WARD ALTERNATE REPRESENTATIVE TO 1 5 Paddle Prairie Metis Settlement Co. of Northern Lights Council MLA Peace River 2 4 Aseniwuche Winewak Nation MD of Greenview Council MLA West Yellowhead 3 4 or 5 Gift lake Metis Settlement Council Peavine metis Settlement Council Whitefish Lake First Nation Chief & Council MD of Big Lakes County Council MLA Lesser Slave Lake 4 3 or 5 East Prairie Metis Settlement Kapawe’no First Nation Chief & Council Page 1 of 2 NORTHLAND SCHOOL DIVISION NO. 61 2019 – 2020 BOARD REPRESENTATIVES Sucker Creek First Nation Chief & Council MD of Big Lakes County Council Northern Lakes College MLA Lesser Slave Lake 5 3 or 4 Peerless Trout First Nation Chief & Council -

Download ATC 2018/2019 Annual Report

2018/2019 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission, Vision, Values . 3 Welcome, Tawow, Sini’e Daniya N’id’a . 4 2018-2019 Years in Review . 6 Education, Culture And Language 10 Employment And Training . 12 Health . 14 Child And Family Services . 16 ATC Cultural Festival 2019 . 18 Finances . .. 19 Operations . 19 2 | Athabasca Tribal Council | atcfn.ca MISSION, VISION, VALUES Mission: Athabasca Tribal Council serves our Nations by providing relevant and innovative programs and services that enrich the well-being, health, and prosperity of our people. We are committed to ensuring the protection of our Inherent rights, our Treaty Rights, and our Traditional Territories. While respecting the autonomy of each Nation, our strength is our unity. Vision: Athabasca Tribal Council, Values: in collaboration with our Collaboration, Respect, Nations, honours our Treaty Integrity, Service, Unity, and supports a thriving, Innovation, Excellence healthy, and self-reliant future for Cree and Dene people. Athabasca Tribal Council Annual Report 2018 - 2019 | 3 WELCOME, TAWOW, SINI’E DANIYA N’ID’A Message from the Board To our respected elders, community members, and partners, In 2018, Athabasca Tribal Council celebrated 30 years of serving our Nations. We have been working diligently to ensure we are growing, adapting, and continuing to improve the way we support our community members. Working with our CEO Karla Buffalo, ATC’s vision has continued to become more defined, with a strong emphasis on identifying the needs of our Nations, and meeting them. As the Board of Directors, it is an honour to help establish the long-term goals and objectives that are helping to achieve the overall vision. -

Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta : Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background. Where available, these website addresses are included in the profiles. PLEASE NOTE The information contained in the Profiles is accurate at the time of publishing.