E-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Corpus Linguistics Paper Coordinator Name & Contact Mo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conferenceabstracts

TENTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LANGUAGE RESOURCES AND EVALUATION Held under the Honorary Patronage of His Excellency Mr. Borut Pahor, President of the Republic of Slovenia MAY 23 – 28, 2016 GRAND HOTEL BERNARDIN CONFERENCE CENTRE Portorož , SLOVENIA CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS Editors: Nicoletta Calzolari (Conference Chair), Khalid Choukri, Thierry Declerck, Marko Grobelnik , Bente Maegaard, Joseph Mariani, Jan Odijk, Stelios Piperidis. Assistant Editors: Sara Goggi, Hélène Mazo The LREC 2016 Proceedings are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License LREC 2016, TENTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LANGUAGE RESOURCES AND EVALUATION Title: LREC 2016 Conference Abstracts Distributed by: ELRA – European Language Resources Association 9, rue des Cordelières 75013 Paris France Tel.: +33 1 43 13 33 33 Fax: +33 1 43 13 33 30 www.elra.info and www.elda.org Email: [email protected] and [email protected] ISBN 978-2-9517408-9-1 EAN 9782951740891 ii Introduction of the Conference Chair and ELRA President Nicoletta Calzolari Welcome to the 10 th edition of LREC in Portorož, back on the Mediterranean Sea! I wish to express to his Excellency Mr. Borut Pahor, the President of the Republic of Slovenia, the gratitude of the Program Committee, of all LREC participants and my personal for his Distinguished Patronage of LREC 2016. Some figures: previous records broken again! It is only the 10 th LREC (18 years after the first), but it has already become one of the most successful and popular conferences of the field. We continue the tradition of breaking previous records. We received 1250 submissions, 23 more than in 2014. We received 43 workshop and 6 tutorial proposals. -

Workshopabstracts

TENTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LANGUAGE RESOURCES AND EVALUATION MAY 23 – 28, 2016 GRAND HOTEL BERNARDIN CONFERENCE CENTRE Portorož , SLOVENIA WORKSHOP ABSTRACTS Editors: Please refer to each single workshop list of editors. Assistant Editors: Sara Goggi, Hélène Mazo The LREC 2016 Proceedings are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License LREC 2016, TENTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LANGUAGE RESOURCES AND EVALUATION Title: LREC 2016 Workshop Abstracts Distributed by: ELRA – European Language Resources Association 9, rue des Cordelières 75013 Paris France Tel.: +33 1 43 13 33 33 Fax: +33 1 43 13 33 30 www.elra.info and www.elda.org Email: [email protected] and [email protected] ISBN 978-2-9517408-9-1 EAN 9782951740891 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS W12 Joint 2nd Workshop on Language & Ontology (LangOnto2) & Terminology & Knowledge Structures (TermiKS) …………………………………………………………………………….. 1 W5 Cross -Platform Text Mining & Natural Language Processing Interoperability ……. 12 W39 9th Workshop on Building & Using Comparable Corpora (BUCC 2016)…….…….. 23 W19 Collaboration & Computing for Under-Resourced Languages (CCURL 2016).….. 31 W31 Improving Social Inclusion using NLP: Tools & Resources ……………………………….. 43 W9 Resources & ProcessIng of linguistic & extra-linguistic Data from people with various forms of cognitive / psychiatric impairments (RaPID)………………………………….. 49 W25 Emotion & Sentiment Analysis (ESA 2016)…………..………………………………………….. 58 W28 2nd Workshop on Visualization as added value in the development, use & evaluation of LRs (VisLR II)……….……………………………………………………………………………… 68 W15 Text Analytics for Cybersecurity & Online Safety (TA-COS)……………………………… 75 W13 5th Workshop on Linked Data in Linguistics (LDL-2016)………………………………….. 83 W10 Lexicographic Resources for Human Language Technology (GLOBALEX 2016)… 93 W18 Translation Evaluation: From Fragmented Tools & Data Sets to an Integrated Ecosystem?.................................................................................................................. -

Classical and Modern Arabic Corpora: Genre and Language Change

This is a repository copy of Classical and modern Arabic corpora: Genre and language change. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/131245/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Atwell, E orcid.org/0000-0001-9395-3764 (2018) Classical and modern Arabic corpora: Genre and language change. In: Whitt, RJ, (ed.) Diachronic Corpora, Genre, and Language Change. Studies in Corpus Linguistics, 85 . John Benjamins , pp. 65-91. ISBN 9789027201485 © John Benjamins 2018.This is an author produced version of a book chapter published in Diachronic Corpora, Genre, and Language Change. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. the publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use or reprint the material in any form. https://doi.org/10.1075/scl.85.04atw. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ “Author Accepted Version” of: Atwell, E. (2018). Classical and Modern Arabic Corpora: genre and language change. -

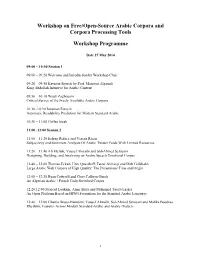

OSACT Workshop on Free/Open-Source Arabic Corpora

Workshop on Free/Open-Source Arabic Corpora and Corpora Processing Tools Workshop Programme Date 27 May 2014 09:00 – 10:30 Session 1 09:00 – 09:20 Welcome and Introduction by Workshop Chair 09:20 – 09:50 Keynote Speech by Prof. Mansour Algamdi King Abdullah Initiative for Arabic Content 09:50 – 10:10 Wajdi Zaghouani Critical Survey of the Freely Available Arabic Corpora 10:10 -10:30 Jonathan Forsyth Automatic Readability Prediction for Modern Standard Arabic 10:30 – 11:00 Coffee break 11:00 -13:00 Session 2 11:00 – 11:20 Eshrag Refaee and Verena Rieser Subjectivity and Sentiment Analysis Of Arabic Twitter Feeds With Limited Resources 11:20 – 11:40 Ali Meftah, Yousef Alotaibi and Sid-Ahmed Selouani Designing, Building, and Analyzing an Arabic Speech Emotional Corpus 11:40 – 12:00 Thomas Eckart, Uwe Quasthoff, Faisal Alshargi and Dirk Goldhahn Large Arabic Web Corpora of High Quality: The Dimensions Time and Origin 12:00 – 12:20 Ryan Cotterell and Chris Callison-Burch An Algerian Arabic / French Code-Switched Corpus 12:20:12:40 Mourad Loukam, Amar Balla and Mohamed Tayeb Laskri An Open Platform Based on HPSG Formalism for the Standard Arabic Language 12:40 – 13:00 Ghania Droua-Hamdani, Yousef Alotaibi, Sid-Ahmed Selouani and Malika Boudraa Rhythmic Features Across Modern Standard Arabic and Arabic Dialects i Editors Hend S. Al-Khalifa King Saud University, KSA King AbdulaAziz City for Science and Abdulmohsen Al-Thubaity Technology, KSA Workshop Organizers/Organizing Committee Hend S. Al-Khalifa King Saud University, KSA King AbdulaAziz -

Fordítástudomány Ma És Holnap

FORDÍTÁSTUDOMÁNY MA ÉS HOLNAP Szerkesztette ROBIN EDINA ZACHAR VIKTOR Szakmai lektor: Klaudy Kinga © Szerkesztők, szerzők, "#$% © L’Harmattan Kiadó, "#$% ISBN &'%-&()-*$*-*#)-% Melyek a (szak)fordító és a fordításkutató munkáját segítő legfontosabb nyelvi korpuszok? Seidl-Péch Olívia E-mail: [email protected] Kivonat: A számítástechnika fejlődésének köszönhetően napjainkra a nyelvi korpuszok a (szak)fordítók és fordításkutatók munkájának fontos segédeszközévé váltak. Az utóbbi évti- zedekben a fordításoktatás is egyre nagyobb hangsúlyt helyezett a korpuszalapú megkö- zelítésre. A korpuszok segítségével rákereshetünk egyes szavak és/vagy mondatrészek szövegkörnyezetben való előfordulására, információkat kaphatunk a kívánt kifejezés szino- nimáiról, jellemző szókapcsolatairól. A korpuszok használata elengedhetetlen a (szak)fordí- tások terminológiai konzisztenciáját biztosító adatbázisok létrehozásához, valamint a (szak) fordító maga is párhuzamos korpuszokat hoz lértre, ahogy a fordítási környezetben fordítási memóriát használ. A fordítástudomány számára a korpuszalapú megközelítés lehetővé tette a célnyelvi szövegek szövegépítő sajátosságainak új vizsgálati szempontok alapján történő leírását, illetve a deskriptív kutatási kérdések alapjául szolgáló objektív szövegelemzési adatok kinyerését. A cikk kitér a (szak)fordítók és a fordításkutatók számára meghatározó korpuszfajtákra, valamint bemutatja a saját kutatási céloknak megfelelő korpusz összeállí- tásának legfontosabb kritériumait. Kulcsszavak: fordításkutatás, fordításoktatás, nyelvi -

This Section Includes 154 Letters of Provided by Members of the CHILDES Consortium Documenting Their Usage of the CHILDES System

This section includes 154 letters of provided by members of the CHILDES consortium documenting their usage of the CHILDES system. These letters are provided by groups representing a total of 232 researchers. On February 4, the following letter was sent out to the [email protected] mailing list, as well as the IASCL (International Association for the Study of Child Language) mailing list. All letters we received were responses to this request. The collection of published papers listed in these letters is now also included in the cumulative bibliography found in section 7. That bibliography includes a total 3104 publications, of which 1500 appeared during the last 5-year period, many of them cited in these letters. Dear Colleague, The NICHD grant for CHILDES is up for renewal this year and I am busy soliciting letters documenting its usage over the last five years. So, if you, your colleagues, or your students have indeed been making use of data or programs in CHILDES, could you please ask them to send me a letter documenting their usage. The new proposal is due March 1. However, I would appreciate receiving your letter as soon as possible. There is no need to send the letter in paper form; email is fine. The new proposal will propose work on: · continued expansion of the database, · web-distributed user tutorials, · creation of a new, user-friendly interface for CLAN, · more powerful search programs that work with the new interface, · fully automatic computation of IPSyn and DSS, · extension of automatic morphosyntactic analysis to more languages, · fuller support for coding of sign language with links to ELAN, · fuller support for Conversation Analysis (CA) coding, · computer-assisted methods for very rapid first-pass transcription, · extended support for video-based transcription, · extended interoperability with other major computer programs, and · a first generation system for web-based collaborative commentary. -

Book of Abstracts

xx Table of Contents Session O1 - Machine Translation & Evaluation . 1 Session O2 - Semantics & Lexicon (1) . 2 Session O3 - Corpus Annotation & Tagging . 3 Session O4 - Dialogue . 4 Session P1 - Anaphora, Coreference . 5 Session: Session P2 - Collaborative Resource Construction & Crowdsourcing . 7 Session P3 - Information Extraction, Information Retrieval, Text Analytics (1) . 9 Session P4 - Infrastructural Issues/Large Projects (1) . 11 Session P5 - Knowledge Discovery/Representation . 13 Session P6 - Opinion Mining / Sentiment Analysis (1) . 14 Session P7 - Social Media Processing (1) . 16 Session O5 - Language Resource Policies & Management . 17 Session O6 - Emotion & Sentiment (1) . 18 Session O7 - Knowledge Discovery & Evaluation (1) . 20 Session O8 - Corpus Creation, Use & Evaluation (1) . 21 Session P8 - Character Recognition and Annotation . 22 Session P9 - Conversational Systems/Dialogue/Chatbots/Human-Robot Interaction (1) . 23 Session P10 - Digital Humanities . 25 Session P11 - Lexicon (1) . 26 Session P12 - Machine Translation, SpeechToSpeech Translation (1) . 28 Session P13 - Semantics (1) . 30 Session P14 - Word Sense Disambiguation . 33 Session O9 - Bio-medical Corpora . 34 Session O10 - MultiWord Expressions . 35 Session O11 - Time & Space . 36 Session O12 - Computer Assisted Language Learning . 37 Session P15 - Annotation Methods and Tools . 38 Session P16 - Corpus Creation, Annotation, Use (1) . 41 Session P17 - Emotion Recognition/Generation . 43 Session P18 - Ethics and Legal Issues . 45 Session P19 - LR Infrastructures and Architectures . 46 xxi Session I-O1: Industry Track - Industrial systems . 48 Session O13 - Paraphrase & Semantics . 49 Session O14 - Emotion & Sentiment (2) . 50 Session O15 - Semantics & Lexicon (2) . 51 Session O16 - Bilingual Speech Corpora & Code-Switching . 52 Session P20 - Bibliometrics, Scientometrics, Infometrics . 54 Session P21 - Discourse Annotation, Representation and Processing (1) . 55 Session P22 - Evaluation Methodologies . -

Best Practices for Speech Corpora in Linguistic Research

Best Practices for Speech Corpora in Linguistic Research Workshop Programme 21 May 2012 14:00 – Case Studies: Corpora & Methods Janne Bondi Johannessen, Øystein Alexander Vangsnes, Joel Priestley and Kristin Hagen: A linguistics-based speech corpus Adriana Slavcheva and Cordula Meißner: GeWiss – a comparable corpus of academic German, English and Polish Elena Grishina, Svetlana Savchuk and Dmitry Sichinava: Multimodal Parallel Russian Corpus (MultiPARC): Multimodal Parallel Russian Corpus (MultiPARC): Main Tasks and General Structure Sukriye Ruhi and E. Eda Isik Tas: Constructing General and Dialectal Corpora for Language Variation Research: Two Case Studies from Turkish Theodossia-Soula Pavlidou: The Corpus of Spoken Greek: goals, challenges, perspectives Ines Rehbein, Sören Schalowski and Heike Wiese: Annotating spoken language Seongsook Choi and Keith Richards: Turn-taking in interdisciplinary scientific research meetings: Using ‘R’ for a simple and flexible tagging system 16:30 – 17:00 Coffee break i 17:00 – Panel: Best Practices Pavel Skrelin and Daniil Kocharov Russian Speech Corpora Framework for Linguistic Purposes Peter M. Fischer and Andreas Witt Developing Solutions for Long-Term Archiving of Spoken Language Data at the Institut für Deutsche Sprache Christoph Draxler Using a Global Corpus Data Model for Linguistic and Phonetic Research Brian MacWhinney, Leonid Spektor, Franklin Chen and Yvan Rose TalkBank XML as a Best Practices Framework Christopher Cieri and Malcah Yaeger-Dror Toward the Harmonization of Metadata Practice -

Proceedings of the First Workshop on Ethics in Natural Language Processing, Pages 1–11, Valencia, Spain, April 4Th, 2017

EACL 2017 Ethics in Natural Language Processing Proceedings of the First ACL Workshop April 4th, 2017 Valencia, Spain Sponsors: c 2017 The Association for Computational Linguistics Order copies of this and other ACL proceedings from: Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, PA 18360 USA Tel: +1-570-476-8006 Fax: +1-570-476-0860 [email protected] ISBN 978-1-945626-47-0 ii Introduction Welcome to the first ACL Workshop on Ethics in Natural Language Processing! We are pleased to have participants from a variety of backgrounds and perspectives: social science, computational linguistics, and philosophy; academia, industry, and government. The workshop consists of invited talks, contributed discussion papers, posters, demos, and a panel discussion. Invited speakers include Graeme Hirst, a Professor in NLP at the University of Toronto, who works on lexical semantics, pragmatics, and text classification, with applications to intelligent text understanding for disabled users; Quirine Eijkman, a Senior Researcher at Leiden University, who leads work on security governance, the sociology of law, and human right; Jason Baldridge, a co-founder and Chief Scientist of People Pattern, who specializes in computational models of discourse as well as the interaction between machine learning and human bias; and Joanna Bryson, a Reader in artificial intelligence and natural intelligence at the University of Bath, who works on action selection, systems AI, transparency of AI, political polarization, income inequality, and ethics in AI. We received paper submissions that span a wide range of topics, addressing issues related to overgeneralization, dual use, privacy protection, bias in NLP models, underrepresentation, fairness, and more. -

The Absence of Arabic Corpus Linguistics: a Call for Creating an Arabic National Corpus

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 12 [Special Issue – June 2013] The Absence of Arabic Corpus Linguistics: A Call for Creating an Arabic National Corpus Mohamed Abdelmageed Mansour, PhD. Assistant Professor of Linguistics Department of English Faculty of Arts Assiut University Egypt. Abstract It is well-known that Arabic linguistic research in the Arabic countries is not based on corpora because Arab countries do not have Arabic corpus linguistics as compared to the existing English corpus linguistics. Corpora are very important in the advancement of different Arabic linguistics such as sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, historical linguistics, geolinguistics, contrastive linguistics, grammar, lexicography, stylistics, language pedagogy, and translation. This concise research calls for creating an Arabic National Corpus (ANC) based on four-step design: planning the corpus, collecting the data, computerizing the corpus and analyzing the corpus. This is considered a huge project that needs the collaboration of different national institutions as well as the governments fund and support. Key Words: Corpus linguistics, corpora, annotation, English corpus linguistics, American National corpus 1. Introduction In a world of a revolutionary computer technology in the field of linguistics, it seems that the common practice among the Arab linguists in the Arab world is very much frustrating. The only thing that an Arab linguist who is conducting a linguistic research can do is painstakingly sitting in his own office either contriving his linguistic data or extracting his own corpus – a tedious process that involves reading through printed texts and manually recording his data. The linguistic results of this huge effort are not highly accurate because these data are far removed from the real language use, not empirical and lack representation.