Lying Aversion and Commitment∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes

GRADUATE GAME THEORY LECTURE NOTES BY OMER TAMUZ California Institute of Technology 2018 Acknowledgments These lecture notes are partially adapted from Osborne and Rubinstein [29], Maschler, Solan and Zamir [23], lecture notes by Federico Echenique, and slides by Daron Acemoglu and Asu Ozdaglar. I am indebted to Seo Young (Silvia) Kim and Zhuofang Li for their help in finding and correcting many errors. Any comments or suggestions are welcome. 2 Contents 1 Extensive form games with perfect information 7 1.1 Tic-Tac-Toe ........................................ 7 1.2 The Sweet Fifteen Game ................................ 7 1.3 Chess ............................................ 7 1.4 Definition of extensive form games with perfect information ........... 10 1.5 The ultimatum game .................................. 10 1.6 Equilibria ......................................... 11 1.7 The centipede game ................................... 11 1.8 Subgames and subgame perfect equilibria ...................... 13 1.9 The dollar auction .................................... 14 1.10 Backward induction, Kuhn’s Theorem and a proof of Zermelo’s Theorem ... 15 2 Strategic form games 17 2.1 Definition ......................................... 17 2.2 Nash equilibria ...................................... 17 2.3 Classical examples .................................... 17 2.4 Dominated strategies .................................. 22 2.5 Repeated elimination of dominated strategies ................... 22 2.6 Dominant strategies .................................. -

Tough Talk, Cheap Talk, and Babbling: Government Unity, Hawkishness

Tough Talk, Cheap Talk, and Babbling: Government Unity, Hawkishness and Military Challenges By Matthew Blake Fehrs Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_____________________ Approved: ___________________________ Joseph Grieco, Supervisor __________________________ Alexander Downes __________________________ Peter Feaver __________________________ Chris Gelpi __________________________ Erik Wibbels Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 ABSTRACT Tough Talk, Cheap Talk, and Babbling: Government Unity, Hawkishness and Military Challenges By Matthew Blake Fehrs Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_____________________ Approved: ___________________________ Joseph Grieco, Supervisor __________________________ Alexander Downes __________________________ Peter Feaver __________________________ Chris Gelpi __________________________ Erik Wibbels An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 Copyrighted by Matthew Blake Fehrs 2008 Abstract A number of puzzles exist regarding the role of domestic politics in the likelihood of international conflict. In particular, the sources of incomplete information remain under-theorized and the microfoundations deficient. This study will examine the role that the unity of the government and the views of the government towards the use of force play in the targeting of states. The theory presented argues that divided dovish governments are particularly likely to suffer from military challenges. In particular, divided governments have difficulty signaling their intentions, taking decisive action, and may appear weak. The theory will be tested on a new dataset created by the author that examines the theory in the context of international territorial disputes. -

Forward Guidance: Communication, Commitment, Or Both?

Forward Guidance: Communication, Commitment, or Both? Marco Bassetto July 25, 2019 WP 2019-05 https://doi.org/10.21033/wp-2019-05 *Working papers are not edited, and all opinions and errors are the responsibility of the author(s). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Reserve Federal Reserve System. Forward Guidance: Communication, Commitment, or Both?∗ Marco Bassettoy July 25, 2019 Abstract A policy of forward guidance has been suggested either as a form of commitment (\Odyssean") or as a way of conveying information to the public (\Delphic"). I an- alyze the strategic interaction between households and the central bank as a game in which the central bank can send messages to the public independently of its actions. In the absence of private information, the set of equilibrium payoffs is independent of the announcements of the central bank: forward guidance as a pure commitment mechanism is a redundant policy instrument. When private information is present, central bank communication can instead have social value. Forward guidance emerges as a natural communication strategy when the private information in the hands of the central bank concerns its own preferences or beliefs: while forward guidance per se is not a substitute for the central bank's commitment or credibility, it is an instrument that allows policymakers to leverage their credibility to convey valuable information about their future policy plans. It is in this context that \Odyssean forward guidance" can be understood. ∗I thank Gadi Barlevy, Jeffrey Campbell, Martin Cripps, Mariacristina De Nardi, Fernando Duarte, Marco Del Negro, Charles L. -

1 SAYING and MEANING, CHEAP TALK and CREDIBILITY Robert

SAYING AND MEANING, CHEAP TALK AND CREDIBILITY Robert Stalnaker In May 2003, the U.S. Treasury Secretary, John Snow, in response to a question, made some remarks that caused the dollar to drop precipitously in value. The Wall Street Journal sharply criticized him for "playing with fire," and characterized his remarks as "dumping on his own currency", "bashing the dollar," and "talking the dollar down". What he in fact said was this: "When the dollar is at a lower level it helps exports, and I think exports are getting stronger as a result." This was an uncontroversial factual claim that everyone, whatever his or her views about what US government currency policy is or should be, would agree with. Why did it have such an impact? "What he has done," Alan Blinder said, "is stated one of those obvious truths that the secretary of the Treasury isn't supposed to say. When the secretary of the Treasury says something like that, it gets imbued with deep meaning whether he wants it to or not." Some thought the secretary knew what he was doing, and intended his remarks to have the effect that they had. ("I think he chose his words carefully," said one currency strategist.) Others thought that he was "straying from the script," and "isn't yet fluent in the delicate language of dollar policy." The Secretary, and other officials, followed up his initial remarks by reiterating that the government's policy was to support a strong dollar, but some still saw his initial remark as a signal that "the Bush administration secretly welcomes the dollar's decline."1 The explicit policy statements apparently lacked credibility. -

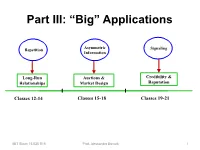

Lecture 19: Costly Signaling Vs. Cheap Talk – 15.025 Game Theory

Part III: “Big” Applications Asymmetric Repetition Signaling Information Long-Run Auctions & Credibility & Relationships Market Design Reputation Classes 12-14 Classes 15-18 Classes 19-21 MIT Sloan 15.025 S15 Prof. Alessandro Bonatti 1 Signaling Games How to Make Communication Credible Chapter 1 (Today): Costly Signaling MIT Sloan 15.025 S15 Prof. Alessandro Bonatti 2 Signaling Examples • Entry deterrence: – Incumbent tries to signal its resolve to fight to deter entrants How can strong informed players distinguish themselves? • Credence Goods: – Used car warranties Can weak players signal-jam? Two of your class projects • Social interactions already using this… – Fashion (pitching a lemon, Estonia) MIT Sloan 15.025 S15 Prof. Alessandro Bonatti 3 The beer & quiche model • A monopolist can be either a tough incumbent or a wimp (not tough). • Incumbent earns 4 if the entrant stays out. • Incumbent earns 2 if the entrant enters. • Entrant earns 2 if it enters against wimp. • Entrant earns -1 if it enters against tough. • Entrant gets 0 if it stays out. MIT Sloan 15.025 S15 Prof. Alessandro Bonatti 4 Beer & Quiche • Prior to the entrant’s decision to enter or stay out, the incumbent gets to choose its “breakfast.” • The incumbent can have beer or quiche for breakfast. • Breakfasts are consumed in public. • Eating quiche “costs” 0. • Drinking beer costs differently according to type: – a beer breakfast costs a tough incumbent 1… – but costs a wimp incumbent 3. MIT Sloan 15.025 S15 Prof. Alessandro Bonatti 5 What’s Beer? Toughness Beer Excess Capacity High Output Low Costs Low Prices Beat up Rivals & Deep Pockets Previous Entrants MIT Sloan 15.025 S15 Prof. -

Cheap Talk and Authoritative Figures in Empirical Experiments ∗

Cheap Talk and Authoritative Figures in Empirical Experiments ∗ Alfred Pang December 9, 2005 Abstract Cheap talk refers to non-binding, costless, non-veriable communications that agents may participate in, before or during a game. It is dicult to observe collusion through cheap talk in empirical experiements. One rea- son for this is our cultural programming that causes us to obey authority gures. 1 Introduction Cheap talk is a term used by game theorists used to describe the communications that take place between agents before the start of a game. The purpose of cheap talk depends on the game being played. For example, if cheap talk is allowed before the start of Battle of the Sexes game, it is used for assisting in the coordination between the agents onto one of the Nash equilibria as shown by Cooper et al [4]. Although cheap talk generally leads to better results in games of coordination as shown by Farrell [2] and Farrell and Rabin [1], this is not always the case. It is known that cheap talk before a singleton Prisoner's Dilemma does not contribute to the cooperation result, if the agents do not have externalities in the result (that is, the agents do not have any utility for a preference to coordinate). Let us examine the attributes of cheap talk: 1. Non-binding - There is no direct penalty for declaring or promising actions and not following through. 2. Costless - There is no cost to the communications. However, it is not completely unlimited. The agents (in real-life and in theory) often have limitations in the communications language and the duration of the cheap talk that limits the possible communications exchanges. -

Self-Enforced Collusion Through Comparative Cheap Talk in Simultaneous Auctions with Entry

Econ Theory (2010) 42:523–538 DOI 10.1007/s00199-008-0403-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Self-enforced collusion through comparative cheap talk in simultaneous auctions with entry Antonio Miralles Received: 14 December 2006 / Accepted: 14 July 2008 / Published online: 21 August 2008 © Springer-Verlag 2008 Abstract Campbell (J Econ Theory 82:425–450, 1998) develops a self-enforced collusion mechanism in simultaneous auctions based on complete comparative cheap talk and endogenous entry, with two bidders. His result is difficult to generalize to an arbitrary number of bidders, since the entry-decision stage of the game is character- ized by strategic substitutes. This paper analyzes more-than-two-bidder, symmetric- prior cases. Two results are proved: (1) as the number of objects grows large, a full comparative cheap talk equilibrium exists and it yields asymptotically fully efficient collusion; and (2) there is always a partial comparative cheap talk equilibrium. All these results are supported by intuitive equilibria at the entry-decision stage (J Econ Theory 130:205–219, 2006; Math Soc Sci 2008, forthcoming). Numerical examples suggest that full comparative cheap talk equilibria are not uncommon even with few objects. Keywords Auctions · Entry costs · Pre-play communication JEL Classification D44 · D82 · C72 Antonio Miralles is grateful to Hsueh-Lyhn Huynh, Bart Lipman, Zvika Neeman, Gregory Pavlov and an anonymous referee for their comments and suggestions. During the research, he received financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Education (SEJ2006-04985), the Fulbright Commission and Boston University. A. Miralles (B) Department of Economics, Boston University, 270 Bay State Rd., Room 543, Boston, MA 02215, USA e-mail: [email protected] 123 524 A. -

Game Theory Model and Empirical Evidence

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Cheap Talk, Trust, and Cooperation in Networked Global Software Engineering: Game Theory Model and Empirical Evidence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99z4314v Author Wang, Yi Publication Date 2015 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Cheap Talk, Trust, and Cooperation in Networked Global Software Engineering: Game Theory Model and Empirical Evidence DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Information and Computer Science by Yi Wang Dissertation Committee: Professor David F. Redmiles, Chair Professor Debra J. Richardson Professor Brian Skyrms 2015 Portion of Chapter 4 c 2013 IEEE. All other materials c 2015 Yi Wang DEDICATION To Natural & Intellectual Beauty ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES vii LIST OF TABLES ix LIST OF ALGORITHMS x ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi CURRICULUM VITAE xiii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xvi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Motivating Observations . 3 1.1.1 Empirical Observations . 3 1.1.2 Summary . 6 1.2 Dissertation Outline . 7 1.2.1 Overview of Each Chapter . 7 1.2.2 How to Read This Dissertation . 9 2 Research Overview and Approach 10 2.1 Overall Research Questions . 10 2.2 Research Approach . 11 2.3 Overview of Potential Contributions . 12 3 Backgrounds 14 3.1 Related Work . 14 3.1.1 Trust in Globally Distributed Collaboration . 14 3.1.2 Informal, Non-work-related Communication in SE and CSCW . -

Perfect Conditional E-Equilibria of Multi-Stage Games with Infinite Sets

Perfect Conditional -Equilibria of Multi-Stage Games with Infinite Sets of Signals and Actions∗ Roger B. Myerson∗ and Philip J. Reny∗∗ *Department of Economics and Harris School of Public Policy **Department of Economics University of Chicago Abstract Abstract: We extend Kreps and Wilson’s concept of sequential equilibrium to games with infinite sets of signals and actions. A strategy profile is a conditional -equilibrium if, for any of a player’s positive probability signal events, his conditional expected util- ity is within of the best that he can achieve by deviating. With topologies on action sets, a conditional -equilibrium is full if strategies give every open set of actions pos- itive probability. Such full conditional -equilibria need not be subgame perfect, so we consider a non-topological approach. Perfect conditional -equilibria are defined by testing conditional -rationality along nets of small perturbations of the players’ strate- gies and of nature’s probability function that, for any action and for almost any state, make this action and state eventually (in the net) always have positive probability. Every perfect conditional -equilibrium is a subgame perfect -equilibrium, and, in fi- nite games, limits of perfect conditional -equilibria as 0 are sequential equilibrium strategy profiles. But limit strategies need not exist in→ infinite games so we consider instead the limit distributions over outcomes. We call such outcome distributions per- fect conditional equilibrium distributions and establish their existence for a large class of regular projective games. Nature’s perturbations can produce equilibria that seem unintuitive and so we augment the game with a net of permissible perturbations. -

On the Robustness of Informative Cheap Talk∗

On the Robustness of Informative Cheap Talk∗ Ying Chen, Navin Kartik, and Joel Sobel† March 23, 2007 Abstract There are typically multiple equilibrium outcomes in the Crawford-Sobel (CS) model of strategic information transmission. This note identifies a simple condi- tion on equilibrium payoffs, called NITS, that selects among CS equilibria. Under a commonly used regularity condition, only the equilibrium with the maximal num- ber of induced actions satisfies NITS. We discuss various justifications for NITS, including recent work on perturbed cheap-talk games. We also apply NITS to two other models of cheap-talk, illustrating its potential beyond the CS framework. Journal of Economic Literature Classification Numbers: C72, D81. Keywords: cheap-talk; babbling; equilibrium selection. ∗We thank Eddie Dekel for encouraging us to write this paper, Melody Lo for comments, and Steve Matthews for making available an old working paper. †Chen: Department of Economics, Arizona State University, email: [email protected]; Kartik and Sobel: Department of Economics, University of California, San Diego, email: [email protected] and [email protected] respectively. Sobel thanks the Guggenheim Foundation, NSF, and the Secretar´ıade Estado de Universidades e Investigaci´ondel Ministerio de Educaci´ony Ciencia (Spain) for financial support. Sobel is grateful to the Departament d’Economia i d’Hist`oria Econ`omicaand Institut d’An`alisi Econ`omica of the Universitat Aut`onomade Barcelona for hospitality and administrative support. 1 Introduction In the standard model of cheap-talk communication, an informed Sender sends a message to an uninformed Receiver. The Receiver responds to the message by making a decision that is payoff relevant to both players. -

Coordination-Free Equilibria in Cheap Talk Games∗

Coordination-Free Equilibria in Cheap Talk Games Shih En Luy Job Market Paper #1 November 16, 2010z Abstract In Crawford and Sobel’s (1982) one-sender cheap talk model, information trans- mission is partial: in equilibrium, the state space is partitioned into a finite number of intervals, and the receiver learns the interval where the state lies. Existing studies of the analogous model with multiple senders, however, offer strikingly different pre- dictions: with a large state space, equilibria with full information transmission exist, as do convoluted almost fully revealing equilibria robust to certain classes of small noise in the senders’information. This paper shows that such equilibria are ruled out when robustness to a broad class of perturbations is required. The surviving equilibria confer a less dramatic informational advantage to the receiver from consulting multi- ple senders. They feature an intuitive interval structure, and are coordination-free in the sense that boundaries between intervals reported by different players do not coin- cide. The coordination-free property implies many similarities between these profiles and one-sender equilibria, and is further justified by appealing to an alternative set of assumptions. I would like to thank my advisor, Attila Ambrus, for his continued support and valuable guidance. I am also grateful to Drew Fudenberg, Jerry Green, Satoru Takahashi, Yuichiro Kamada and participants of the Theory lunch at Harvard for helpful comments and conversations. yDepartment of Economics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138. Email: [email protected] zThis version is identical to the November 12, 2010 version, save for one added sentence at the bottom of page 16. -

1 Competition Policy Implications from Game Theory

Competition Policy Implications from Game Theory: an Evaluation of the Commission's Policy on Information Exchange § 1 Introduction One of the most vexing question for those that apply competition rules concerns how to assess oligopolies. When will market conditions lead companies in a oligopolistic market to compete fiercely on all important parameters (price, quality and innovation) and when will competition be replaced, on one or all parameters, by collusive behaviour?1 The first idea for this paper was to investigate which are the competition policy implications from non-cooperative game theory.2 Emphasis will be put on policy implications for the treatment of information exchange between companies. The main conclusions which can be drawn from non-cooperative game theory are summarized in section 2. Within the logic of this theory these main conclusions lead to three general implications for competition policy as described in sections 3 to 5. In sections 6 and 7 the implications for the treatment of information exchange are considered. This is done in section 6 by paying attention to the nature of the information that is exchanged. In section 7 the market structure, the other factor that determines the effect of information exchange on competition, is considered. During the research it appeared that the usefulness of non-cooperative game theory for competition policy was rather limited. When looking at the influence of market structure for section 7 it became clear that models were rather incomplete. Moreover, the assumptions underlying non-cooperative game theory, especially concerning what is defined as rational behaviour, made it unable to explain a good part of the collusive behaviour that can be observed in experiment and reality.