Page 1 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 350 247 SO 022 642 AUTHOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Front Cover

Front Cover 1 “We hold a treasure not made of gold, in earthen vessels, wealth untold, one treasure only: the Lord, the Christ, in earthen vessels.” 2 Corinthians 4:7 3 29 September 2019 Welcome, dear family and friends, We are thrilled that you can join us for a final celebration of this amazing journey on which God has taken us. We are aging, hopefully with a bit of style and grace, but know that the years will surely diminish our ability to do events together. Before our minds and bodies will no longer allow us to stand before you, the five of us want to honor you with one last concert, an opportunity for you and for us to give thanks to the One who has been with us and gone before us every step of the way. We’ve “come home” to this place where our journey began so many years ago. This represents the closing of a circle for us. We recorded our first album, Neither Silver Nor Gold, just blocks from here. The cover art on this concert program harkens back to the Lord of Light album that we recorded here. And today we circle back again, coming together one last time, to be with you, our family and friends. Just to be clear, this final concert doesn’t mean that the St. Louis Jesuits are going to disappear any time soon. We already have several individual projects in the works. There are still new dreams to dream, new songs to write and new prayers to pray. -

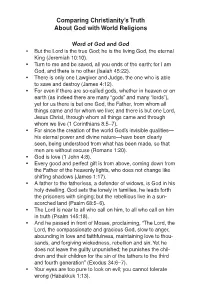

Comparing Christianity's Truth About God with World Religions

ComparingChristianitywithWReligions e-book:Layout 1 3/4/11 9:09 AM Page 8 Comparing Christianity’s Truth About God with World Religions Word of God and God • But the Lord is the true God; he is the living God, the eternal King (Jeremiah 10:10). • Turn to me and be saved, all you ends of the earth; for I am God, and there is no other (Isaiah 45:22). • There is only one Lawgiver and Judge, the one who is able to save and destroy (James 4:12). • For even if there are so-called gods, whether in heaven or on earth (as indeed there are many “gods” and many “lords”), yet for us there is but one God, the Father, from whom all things came and for whom we live; and there is but one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom all things came and through whom we live (1 Corinthians 8:5–7). • For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities— his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that men are without excuse (Romans 1:20). • God is love (1 John 4:8). • Every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of the heavenly lights, who does not change like shifting shadows (James 1:17). • A father to the fatherless, a defender of widows, is God in his holy dwelling. God sets the lonely in families, he leads forth the prisoners with singing; but the rebellious live in a sun- scorched land (Psalm 68:5–6). -

Tethered a COMPANION BOOK for the Tethered Album

Tethered A COMPANION BOOK for the Tethered Album Letters to You From Jesus To Give You HOPE and INSTRUCTION as given to Clare And Ezekiel Du Bois as well as Carol Jennings Edited and Compiled by Carol Jennings Cover Illustration courtesy of: Ain Vares, The Parable of the Ten Virgins www.ainvaresart.com Copyright © 2016 Clare And Ezekiel Du Bois Published by Heartdwellers.org All Rights Reserved. 2 NOTICE: You are encouraged to distribute copies of this document through any means, electronic or in printed form. You may post this material, in whole or in part, on your website or anywhere else. But we do request that you include this notice so others may know they can copy and distribute as well. This book is available as a free ebook at the website: http://www.HeartDwellers.org Other Still Small Voice venues are: Still Small Voice Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/claredubois/featured Still Small Voice Facebook: Heartdwellers Blog: https://heartdwellingwithjesus.wordpress.com/ Blog: www.stillsmallvoicetriage.org 3 Foreword…………………………………………..………………………………………..………….pg 6 What Just Happened?............................................................................................................................pg 8 What Jesus wants you to know from Him………………………………………………………....pg 10 Some questions you might have……………………………………………………….....................pg 11 *The question is burning in your mind, ‘But why?’…………………....pg 11 *What do I need to do now? …………………………………………...pg 11 *You ask of Me (Jesus) – ‘What now?’ ………………………….….....pg -

If You Believe CD Insert

As always, if we can help you in any way, please contact the church here at: P.O. Box 68309 Indianapolis, IN 46268 USA (317) 335-4340 E-mail: [email protected] For more teaching about Jesus and His church, put this CD in your computer. This CD is not for sale at any price. (2 Corinthians 2:17, Matthew 10:8) This is not intended, of course, to be a “professional music production” that has been “performed” by “artists” in the “industry.” It is simply a scrapbook of a few of the hundreds of songs and other gifts that disciples of Jesus here in our city have offered to the other saints and their King during gatherings of Believers. There is no attempt here to compete with the system of the world, nor to engage “professionals” in vocals or instrumentation. No “nominal” christians (if there is such a thing, Luke 9:57-62) were involved in any of this work just because of “talent.” Only followers of Jesus. These are our gifts to one another and Jesus, expressed in Life day-by-day... and now a gift to you. Just Family, loving on one another, and Jesus... and you. (Hey! We would love it if this page only had the flowers and the address! Unfortunately, due to ambition, greed, “conforming to the patterns of the world” and the like in the culturalized and popularized christianity of the day, we needed to add a few other thoughts. :) ) © 2000 Lordin Publishing. All Rights Reserved. These songs were intended to be authored by and to belong to Jesus. -

Transcript for Art Works Webinar in PDF Format

*********DISCLAIMER!!!************ THE FOLLOWING IS AN UNEDITED ROUGH DRAFT TRANSLATION FROM THE CART PROVIDER’S OUTPUT FILE. THIS TRANSCRIPT IS NOT VERBATIM AND HAS NOT BEEN PROOFREAD. THIS IS NOT A LEGAL DOCUMENT. THIS FILE MAY CONTAIN ERRORS. THIS TRANSCRIPT MAY NOT BE COPIED OR DISSEMINATED TO ANYONE UNLESS PERMISSION IS OBTAINED FROM THE HIRING PARTY. SOME INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN MAY BE WORK PRODUCT OF THE SPEAKERS AND/OR PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS AMONG PARTICIPANTS. HIRING PARTY ASSUMES ALL RESPONSIBILITY FOR SECURING PERMISSION FOR DISSEMINATION OF THIS TRANSCRIPT AND HOLDS HARMLESS Texas Closed Captioning, LLC FOR ANY ERRORS IN THE TRANSCRIPT AND ANY RELEASE OF INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN. ****************DISCLAIMER!!!**************** >> Everyone is so quiet. >> We're ready. >> We're doing our power thought, right? >> That's right. >> Sorry, we had interpreter issues. >> It's all right. >> They're connecting now. Yes, Ma'am, there's one of them. So you can change your name, Nancy, when I put your name in the system, I put a capital A. If you click on the ellipses you can correct that. Let's see ‑‑ we're still missing Grant. And Texas Closed Captioning is here. So let me do this. Is that the bottom? Okay. >> Yes, looks good. >> Okay, got that. I am still missing Grant. Patience, patience. Oh, so it's denim day which is created in response to a 1999 sexual assault ruling in an Italian court which stated that the victim's tight jeans implied consent to rape. >> Implied consent? Oh, nice. >> So denim day brings awareness to sexual assault and honors survivors who have experienced this trauma. -

Song List by Artist

Song List by Artist Artist Song Name 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT EAT FOR TWO WHAT'S THE MATTER HERE 10CC RUBBER BULLETS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 ANYWHERE [FEAT LIL'Z] CUPID PEACHES AND CREAM 112 FEAT SUPER CAT NA NA NA NA 112 FEAT. BEANIE SIGEL,LUDACRIS DANCE WITH ME/PEACHES AND CREAM 12TH MAN MARVELLOUS [FEAT MCG HAMMER] 1927 COMPULSORY HERO 2 BROTHERS ON THE 4TH FLOOR COME TAKE MY HAND NEVER ALONE 2 COW BOYS EVERYBODY GONFI GONE 2 HEADS OUT OF THE CITY 2 LIVE CREW LING ME SO HORNY WIGGLE IT 2 PAC ALL ABOUT U BRENDA’S GOT A BABY Page 1 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name HEARTZ OF MEN HOW LONG WILL THEY MOURN TO ME? I AIN’T MAD AT CHA PICTURE ME ROLLIN’ TO LIVE & DIE IN L.A. TOSS IT UP TROUBLESOME 96’ 2 UNLIMITED LET THE BEAT CONTROL YOUR BODY LETS GET READY TO RUMBLE REMIX NO LIMIT TRIBAL DANCE 2PAC DO FOR LOVE HOW DO YOU WANT IT KEEP YA HEAD UP OLD SCHOOL SMILE [AND SCARFACE] THUGZ MANSION 3 AMIGOS 25 MILES 2001 3 DOORS DOWN BE LIKE THAT WHEN IM GONE 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO LOVE CRAZY EXTENDED VOCAL MIX 30 SECONDS TO MARS FROM YESTERDAY 33HZ (HONEY PLEASER/BASS TONE) 38 SPECIAL BACK TO PARADISE BACK WHERE YOU BELONG Page 2 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN, THE CAUGHT UP IN YOU HOLD ON LOOSELY IF I'D BEEN THE ONE LIKE NO OTHER NIGHT LOVE DON'T COME EASY SECOND CHANCE TEACHER TEACHER YOU KEEP RUNNIN' AWAY 4 STRINGS TAKE ME AWAY 88 4:00 PM SUKIYAKI 411 DUMB ON MY KNEES [FEAT GHOSTFACE KILLAH] 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS [FEAT NATE DOGG] A BALTIMORE LOVE THING BUILD YOU UP CANDY SHOP (INSTRUMENTAL) CANDY SHOP (VIDEO) CANDY SHOP [FEAT OLIVIA] GET IN MY CAR GOD GAVE ME STYLE GUNZ COME OUT I DON’T NEED ‘EM I’M SUPPOSED TO DIE TONIGHT IF I CAN’T IN DA CLUB IN MY HOOD JUST A LIL BIT MY TOY SOLDIER ON FIRE Page 3 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name OUTTA CONTROL PIGGY BANK PLACES TO GO POSITION OF POWER RYDER MUSIC SKI MASK WAY SO AMAZING THIS IS 50 WANKSTA 50 CENT FEAT. -

Escaping Eden

Escaping Eden Chapter 1 I wake up screaming. Where am I? What’s going on? Why do I feel so cold? It’s dark. I look around, blinking sleep from my eyes. I notice a window somewhere in the back of the room. It’s open and moonlight shines through, casting a square beam of light across the floor. A breeze drifts in, and white curtains float like pale ghosts in the darkness. In the narrow light of the moon, I see that the carpet is burgundy. I also see the outlines of furniture. My head vaguely aching, I look at the shadows scattered messily across the room. I feel like sweeping them up to make room for light. I shake off the urge. Stop being delusional. There’s a funny smell in the air, like a mixture of old home mustiness and laboratory sterilization. I realize that I’m lying on the floor. Why am I not on the bed? The last thing I remember is pain. Maybe that’s why I woke up screaming. The pain was intense. The pain was… cold. I decide to swallow my fear. It tastes terrible. I stand up and my neck aches. As I rub my hand across it, my bones crack like I haven’t moved in a long time. I whisper to myself. “As Grandpa always said…” My train of thought rolls off into the distance. Where was I going with this? Who is “Grandpa”? I put my hand on my sweaty forehead. I must be tired. I look for a light switch by approaching the walls and groping around. -

A Creative Biography of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Through the Lens of Her Interpersonal Relationships

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 2-26-2021 Mary: A Creative Biography of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley through the Lens of Her Interpersonal Relationships Julien-Pierre E. Campbell Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Fiction Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Campbell, Julien-Pierre E., "Mary: A Creative Biography of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley through the Lens of Her Interpersonal Relationships" (2021). University Honors Theses. Paper 980. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.1004 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Campbell 1 Mary A Creative Biography of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Through the Lens of her Interpersonal Relationships By Julien-Pierre “JP” Campbell Campbell 2 Percy Shelley 27 June 1814 Night falls slowly around us. The sky has rioted with all of God’s colors and at last succumbed to the pale blue of the gloaming. He stares hard at the sky. Who can know the exact thoughts that are stirred behind that princely brow? His eyes bear the faraway look I’ve come to associate with brilliance. He’s composing. Perhaps I stay quiet long enough -- Lord knows our sepulchral companions will -- he will speak verse. I’m sure I could observe him for rapturous eons. His cheeks are flushed and his curls are mussed. -

Carthusian Diurnal

Carthusian Diurnal Volume I CARTHUSIAN DIURNAL Volume I Little Hours of the Canonical Office Office of the Blessed Virgin Penitential Psalms and Litany of the Saints Office of the Dead Grande Chartreuse 1985 We approve this English edition of the CARTHUSIAN DIURNAL (Volume I). La Grande Chartreuse, in the Feast of the Transfiguration 1985. Fr. Andre Prior of Chartreuse Introduction INTRODUCTION Why this Office? The Second Vatican Council expresses itself on the subject of the Office in these words: Jesus Christ, High Priest of the New and Eternal Covenant, taking human nature, introduced into this earthly exile that hymn which is sung throughout all ages in the halls of heaven. He attaches to himself the entire community of mankind and has them join him in singing his divine song of praise ... The Divine Office, in keeping with ancient Christian tradition, is so devised that the whole course of the day and night is made holy by the praise of God. Therefore, when this wonderful song of praise is Correctly celebrated by priests and others deputed to it by the Church, or by the faithful praying together with a priest in the approved form, then it is truly the voice of the Bride herself addressed to her Bridegroom. It is the very prayer which Christ himself together with his Body addresses to the Father. Hence all who take part in the Divine Office are not only performing a duty for the Church, they are also sharing in what is the greatest honor for Christ's Bride; for by offering these praises to God they are standing before God's throne in the name of the Church, their Mother. -

![1 a Thief in the Night [A Book of Raffles' Adventures]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1909/1-a-thief-in-the-night-a-book-of-raffles-adventures-3271909.webp)

1 a Thief in the Night [A Book of Raffles' Adventures]

1 A Thief in the Night [A Book of Raffles' Adventures] by E. W. Hornung Out of Paradise If I must tell more tales of Raffles, I can but back to our earliest days together, and fill in the blanks left by discretion in existing annals. In so doing I may indeed fill some small part of an infinitely greater blank, across which you may conceive me to have stretched my canvas for the first frank portrait of my friend. The whole truth cannot harm him now. I shall paint in every wart. Raffles was a villain, when all is written; it is no service to his memory to glaze the fact; yet I have done so myself before to-day. I have omitted whole heinous episodes. I have dwelt unduly on the redeeming side. And this I may do again, blinded even as I write by the gallant glamour that made my villain more to me than any hero. But at least there shall be no more reservations, and as an earnest I shall make no further secret of the greatest wrong that even Raffles ever did me. I pick my words with care and pain, loyal as I still would be to my friend, and yet remembering as I must those Ides of March when he led me blindfold into temptation and crime. That was an ugly office, if you will. It was a moral bagatelle to the treacherous trick he was to play me a few weeks later. The second offence, on the other hand, was to prove the less serious of the two against society, and might in itself have been published to the world years ago. -

WEEK 85, DAY 1 PSALMS 74, 77, 79, and 80 Good Morning. This Is

WEEK 85, DAY 1 PSALMS 74, 77, 79, and 80 Good morning. This is Pastor Soper and welcome to Week 85 of Know the Word. May I encourage you by saying that we are now less than six weeks away from finishing Know the Word? Then you will be able to say that you have carefully and prayerfully read the entire Bible, from cover to cover! That will, I believe, turn out to be one of the greatest and most beneficial accomplishments of your entire Christian life! I can honestly tell you that producing these recordings has been one of the greatest and most blessed accomplishments of my life as a Christian! Well, today we read Psalms 74, 77, 79 and 80. These Psalms are all found in Book 3 of the Psalter. (You will remember that Book 2 ended with the expression at the end of Psalm 72: “This concludes the prayers of David, son of Jesse,” even though several more Psalms bearing his name will be found mostly in Books 4 and 5). We also learned that there are five Books of Psalms, which appear to roughly correspond to the five Books of Moses. I have to confess to you, however, that the division between the five books have always seemed a bit arbitrary to me and I found myself wondering about that again this week. It is true, as some scholars have noted, the Psalms in Book 1 frequently use the name “Jehovah” or “Lord,” while the second Book seems to highlight the name “Elohim” or “God.” It is also apparent, as you may have quickly noticed this morning, that most of the Psalms in Book 3 show some evidence of being “exilic,” that is, they were written after the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians. -

Says the Lord

February 2021 VOL 63 NO. 8 “. .The Scripture Cannot Be Broken.” ( John 10:35) "Now, therefore," says the Lord, "Turn to Me with all your heart, With fasting, with weeping, and with mourning." So rend your heart, and not your garments; Return to the Lord your God, for He is gracious and merciful. -- Joel 2:12-13 Lutheran Spokesman – VOL 63 NO. 8 – February 2021 1 Page 12 In This Issue February 2021 The Ashes of Repentance ..................................... 3 WHAT’S NEW WITH YOU Peace on the Prairie / Mission, SD ................ 10-11 Where You Go, I Go ............................................... 4 NOTES FROM THE FIELD A HYMN OF GLORY LET US SING In Memory of Mary B. .......................................... 12 “What Wondrous Love Is This” ............................ 5 ILC NEWSLETTER ................................................. 13 The Lord Is My Shepherd ..................................... 6 Bread of Life Readings, February 2021 ............. 14 A Fiery Member in our Bodies ............................. 7 IN THE PIPELINE WALTHER’S LAW AND GOSPEL Benjamin Hansen ................................................ 15 Two Principles for Correct Preaching ................. 8 SEEN IN PASSING / ANNOUNCEMENTS ............. 16 ERROR’S ECHO Monophysitism ........................... 9 The Lutheran Spokesman (USPS 825580) (ISSN 00247537) is published monthly by Material submitted for publication should be sent to Editor Paul Naumann three months the Church of the Lutheran Confession, 501 Grover Road, Eau Claire, WI 54701, and before date of publication. Announcements and other short notices should also be sent is an official organ of the Church of the Lutheran Confession (CLC). Website address: to Editor Naumann. www.clclutheran.org Business Manager: Rev. James Sandeen, 501 Grover Road, Eau Claire, WI, 54701. E-mail Periodicals postage paid at Eau Claire, WI and additional mailing offices.