Theologies of Power and Rituals of Productivity in a Tamil Nadu Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pappankulam – a Village of Brahmins and Four Vedas

1 Pappankulam – A Village of Brahmins and Four Vedas - Shanmugam P Blogger, poet and the author of “The Truth About Spiritual Enlightenment: Bridging Science, Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta” and “Discovering God: Bridging Christianity, Hinduism and Islam” Blogs: http://nellaishanmugam.wordpress.com (English) http://poemsofshanmugam.wordpress.com (Tamil) Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCwOJcU0o7xIy1L663hoxzZw/ 2 Introduction This short ebook is about a small south Indian village called ‘Pappankulam’ which has many temples and interesting stories associated with it. This ebook includes deep in depth research on the origins of the myths. This ebook will try to answer the following questions: 1) Why was the Indian society divided into four varnas? 2) Were Shudras (working class) denied access to Vedic study? If so, why? 3) Who is a Brahmin? 4) Why did Rama kill Shambuka, a Shudra ascetic? 5) What is Svadharma? 6) What is the essential message of Vedas? The pdf has links to many important posts that I have written in the past three years. By going through all of them, you can get the complete picture when it comes to the history of religions. (The content of this free ebook has also been published online in my blog at Pappankulam – A Village of Brahmins and Four Vedas ) - Shanmugam P 3 Table of Contents Pappankulam – A Village of Brahmins and Four Vedas 1 Introduction 2 Pappankulam - A Land Donated to a Brahmin 5 Goddess Saraswati and the Curse of the sage Durvasa 8 Vada Kalai Nayagi - The Goddess of arts 10 The Confluence -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

RELIGION in KAPPALUR INSCRIPTIONS Dr.G.Rangarajan Asst.Professor, Department of History, Government Arts College, Thiruvannamalai-606603

© 2017 JETIR June 2017, Volume 4, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) RELIGION IN KAPPALUR INSCRIPTIONS Dr.G.Rangarajan Asst.Professor, Department Of History, Government arts College, Thiruvannamalai-606603. Human beings have fear of nature’s power. He believes that if he worships it, he can escape from its rage. On this basis, he started the worship of nature along with the relevant celebrations. Celebrations and festivals originated on the belief that if he made sacrifices, he could product himself control from nature. In due course, people began to give shape to nature and prayer. In this way, idol worship could have started among the people. Ancient people had fear of thunder, rain and lightning. They also believed that ghosts were responsible for diseases, and hence, they began to worship them. The famous psychologist, Sigmund Freud, also argues that the fear of nature and plight after death has made men worship nature.1 There is a proverb among the Tamils: “Don’t live in a village where there is no temple”. If something good happens, they ascribe it to god’s blessing and if something bad happens, they ascribe it to god’s wrath. Villagers worship rural deities with belief and fear. Tamil Nadu is the state, which patronizes many religions. There are very many evidences to prove that since the Sangam period, onwards Tamils have lived with religious tolerance. They either castigated or punished those who belittled the religion, which was followed by the majority of people. There were no religious quarrels during the Sangam period. Religious perseverance was the characteristic of those days. -

Southern India

CASTES AND TRIBES rsf SOUTHERN INDIA E, THURSTON THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES CASTES AND TRIBES OF SOUTHERN INDIA CASTES AND TRIBES OF SOUTHERN INDIA BY EDGAR THURSTON, C.I.E., Madras Government Superintendent, Museum ; Correspondant Etranger, Socie'te'id'Anthropologie de Paris; Socio Corrispondant, Societa Romana di Anthropologia. ASSISTED BY K. RANGACHARI, M.A., of the Madras Government Museum. VOLUME VI P TO S GOVERNMENT PRESS, MADRAS 1909. College Library CASTES AND TRIBES OF SOUTHERN INDIA. VOLUME VI. filALLI OR VANNIYAN. Writing concerning this caste the Census Superintendent, 1871* records that "a book has been written by a native to show that the Pallis (Pullies or Vanniar) of the south are descendants of the fire races (Agnikulas) of the Kshatriyas, and that the Tamil Pullies were at one time the shepherd kings of Egypt." At the time of the census, 1871, a petition was submitted to Government by representatives of the caste, praying that they might be classified as Kshatriyas, and twenty years later, in con- nection with the census, 1891, a book entitled ' Vannikula ' Vilakkam : a treatise on the Vanniya caste, was compiled by Mr. T. Aiyakannu Nayakar, in support of the caste claim to be returned as Kshatriyas, for details concerning which claim I must refer the reader to the book itself. In 1907, a book entitled Varuna Darpanam (Mirror of Castes) was published, in which an attempt is made to connect the caste with the Pallavas. Kulasekhara, one of the early Travancore kings, and one of the most renowned Alwars reverenced by the Sri Vaishnava community in Southern India, is claimed by the Pallis as a king of their caste. -

Janakpurdham.Pdf

JANAKPURDHAM the land steeped in mythology The information contained in this book has been outsourced from an expert writer while every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and reliability. However, in case of lapses and discrepancies, revisions and updates would be subsequently carried out in the forthcoming issues. 2009 Edition © NTB Copy Right Images: Thomas Kelly Contents Background Historical and mythological background of Janakpurdham 3 Pilgrimage Importance of Mithila from Pilgrimage and Touristic Point of view 5 Temples Notable temples of Janakpurdham 8 Ponds Some Important Ponds of Janakpurdham 11 Cultural dance Unique Cultural Dances of Janakpurdham 14 Festivals Annual Festivals of Mithilanchal and Janakpurdham 17 THE NAME JANAKPURDHAM IS COMPOSED OF THREE WORDS IN THE DEVNAGARI SCRIPT, I.E., ‘JaNAK’, ‘PUR’ ANd ‘DHam’, wHICH MEAN ‘fATHER’, ‘vILLAGE’ aND ’RENOWNED PLACE FOR PILGRIMAGE’ RESPectiVELY. A traditional mud house ornamented with hand paintings. Historical and mythological background of Janakpurdham Janakpurdham, presently the headquarters of both Janakpur zone and Dhanusha district, was the capital of King Janak’s ancient Mithila Kingdom during the Treta Yug, or period, nearly 12,000 years ago. The name Janakpurdham is composed of three words in the Devnagari script, i.e., ‘Janak’, ‘Pur’ and ‘Dham’, which mean ‘father’, ‘village’ and ‘renowned place for pilgrimage’ respectively. Named after the sage king, Janak, Janakpurdham, however, also encompasses Mithilanchal, or the Mithila region. Balmiki’s epic Ramayan on Aryan culture and Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas authenticate this. The boundary of Mithila is cited in the The great poet and composer of Mithila, Mithila Mahatmaya Khanda (part) of Brihad Bhasha Ramayan Chanda Jha, has defined the Vishnupuran in Sanskrit as: boundary as follows (in Maithili): “Kaushkitu samarbhya Gandaki “Ganga Bahathi janik dakshin dish purwa madhigamyawai, Kaushiki dhara, Yojanani chatturvishadyam parikeertitah. -

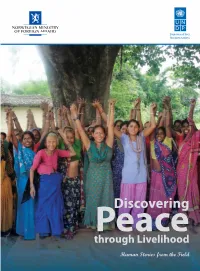

Discovering Through Livelihood

NORWEGIAN MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFFAIRS Empowered lives. Resilient nations. PeaceDiscovering through Livelihood Human Stories from the Field NORRWEGIAN MINISTRRY OF FOREIGN AFFFAIRS Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Human Stories from the Field Discovering Peace through Livelihood November 2011 Empowered lives. Resilient nations. UNDP is the UN’s global development network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. Copyright © UNDP 2011 All rights reserved United Nations Development Programme UN House, Pulchowk, G.P.O. Box: 107 Kathmandu Nepal Tel: + (977 - 1) 5523200 Fax: + (977 - 1) 5523991, 5523986 www.undp.org.np Design: Flying Colors Advertising Pvt. Ltd. Bhotahity, Kathmandu Tel.: +977 1 4219537 E-mail: [email protected] Printing: Pioneer Concept & Printers Tripureshowr, Kathmandu Tel.: +977 1 4263742 E-mail: [email protected] NORRWEGIAN MINISTRRY OF FOREIGN AFFFAIRS Empowered lives. Resilient nations. PeaceDiscovering through Livelihood Human Stories from the Field v Foreword vi Acknowledgements viii Acronyms xi Introduction 1 From Nobody to Somebody 7 Empowering Communities 12 Little Smiles that Tell a Story 15 When Small Means Big for Jipsi 18 Fat Cash Income for Displaced Family 20 Joy of Bina and Bishnu 22 Nasira’s Coins and Confidence 24 Income through Delicacy 26 Way to Say No to Foreign Employment 28 Lighting Homes And Hopes 30 Empowerment through Information 32 Judging Social Changes 34 Good Water for Good Life 37 Innovative Ideas for Peace 40 Declaration of Free Zone on UN Day 42 Message Behind a Cup of Tea 44 Tribute to my Brother 46 Changing the Past 50 Building Synergies for Peace 53 Delight of Representation 56 Transformations of Doms 59 From Catching Mice to Making Money 62 Courage Not Seen Before 64 Song for Social Change DISCOVERING PEACE THROUGH LIVELIHOOD iv Foreword Recovery from conflict is essential to sustain peace in a country like Nepal that is passing through a historical transition. -

The Village Gods of South India

The George A. Wnrburton /Memorial Collection Presented to The Canadian Sctwx)! of MLSSJOILS by t\. /\. Hvde, Lsci., Wichita, Kansas. FROM-THE- LIBRARYOF TRINITYCOLLEGETORONTO THE RELIGIOUS LIFE OF INDIA EDITED BY J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt., LITERARY SECRETARY, NATIONAL COUNCIL, YOUNG MEN S AND CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS, INDIA, BURMA CEYLON ; AND NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., D.Litt. ALREADY PUBLISHED THE AHMADIYA MOVEMENT. By H. A. WALTER, M.A. THE CHAMARS. By G. W. BRIGGS, M.Sc., Cawnpore. UNDER PREPARATION THE HINDU RELIGIOUS YEAR. By M.M. UNDERBILL, B.A., B.Litt., Nasik. THE VAISHNAVISM OF PANDHARPUR. By NICOL MAC NICOL, M.A., D.Litt., Poona. THE CHAITANYAS. By M. T. KENNEDY, M.A., Calcutta. THE SRl-VAISHNAVAS. By E. C. WORMAN, M.A., Madras. THE RAMANANDIS. By C. T. GROVES, M.A., Fyzabad. KABlR AND HIS FOLLOWERS. By F. E. KEAY, M.A., Jubbulpore. "^ THE DADUPANTHlS. By W. G. ORR, M.A., B.D., Jaipur. THE VlRA SAIVAS. By W. E. TOMLINSON, Mangalore, and W. PERSTON, Tumkur. ^w "THE TAMIL SAIVA SIDDHANTA. By GORDON MATTHEWS, M.A., B.D., Madras, and J. S. MASILAMANI, B.D., Pasumalai. THE BRAHMA MOVEMENT. By MANILAL C. PAREKH, B.A.. Rajkot, Kathiawar. THE RAMAKRISHNA MOVEMENT. By J. N. C. GANGULY, B.A., Calcutta. THE KHOJAS. By W. M. HUME, B.A., Lahore. THE MALAS AND MADIGAS. By the BISHOP OF DORNAKAL, P. B. EMMET, B.A., Kurnool, and S. NICHOLSON, Cuddapah. THE DHEDS. By MRS. SINCLAIR STEVENSON, M.A., Sc.D., Rajkot, Kathiawar. THE MAHARS. By A. ROBERTSON, M.A., Poona. THE BHILS. -

Samvit Knowledge Beyond Time

Issue 7 A Quarterly Student Journal Samvit Knowledge beyond time ...... visit us @ www.amrita.edu/samvit February 2014 Samskriti, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Amritapuri Campus Editorial In today’s modern world, we are caught up by the illusion that the external world is the only source of happiness contrary to the fact that real happiness or bliss lies within ourselves. So how are we as Indians and citizens of the modern world going to establish this truth? This is when we should go back and draw upon the treasure trove of wisdom we have inherited from our ancestors and see how they lived, our ancestors were not mere people “The curse upon our society is ignorance about our traditions and the basic spiritual they were rishis, kings, people with principles. This needs to change. Amma has visited so many countries around the world wisdom who had accomplished and personally met so many people there. All of them, including the indigenous people and truly laid down and practiced of Australia, Africa and America, take pride in their heritage and traditions. But here a systematic way of life. But most in India, many among us neither have understanding nor pride. In fact some of us even importantly they taught us to ridicule our culture. Only if we first lay a strong foundation can we hope to erect a tall love and it can be done practicing building. Similarly only if we have knowledge and pride in our forefathers and heritage, non attachment and nonviolence. can we create a radiant present and future”. Education was an intertwined essence of both worldly and spiritual knowledge, which resulted in good leaders and quality citizens. -

Temples Within Chennai City

Temples within Chennai City 1 As the famous Tamil poetess AUVAYYAR says in Her Legendary presentation of cluster of hymns “Kovil illatha ooril kudi irukkathe” Please don’t reside in a place where there is no temple. The Statement of our forefathers is sacrosanct because the temple indicates that the community is graced by the presence of God and that its Citizens form a moral community. A Community identifies and is identified by others with its temples. It has been our ancient endavour to lead a pious life with full dedication to the services of the Lord. Sri Paramacharya of Kanchi Mutt has repeatedly called devotees and stressed the importance of taking care of old temples - which requires enormous power of men and money - instead of constructing new temples in cities. As you may be aware, there are thousands of temples in dilapidated condition and requires constant maintenance work to be undertaken. There are many shiva lingas of ancient temples found under trees and also while digging. In ancient times, these lingas were 'Moolavars' of temples built by several kings. After conquests and devastations by foreign invaders, Indian temples were destructed and the sacred deities were thrown away and many were broken. The left out deities are found later. Of them, some are unidentified. Those who attempt to construct temples for gods are freed from the sins of a thousand births. Those who think of building a temple in their minds are freed from the sins of a hundred births. Those who contribute to the cause of a temple are bestowed with divine virtues and blessings. -

Abhiyoga Jain Gods

A babylonian goddess of the moon A-a mesopotamian sun goddess A’as hittite god of wisdom Aabit egyptian goddess of song Aakuluujjusi inuit creator goddess Aasith egyptian goddess of the hunt Aataentsic iriquois goddess Aatxe basque bull god Ab Kin Xoc mayan god of war Aba Khatun Baikal siberian goddess of the sea Abaangui guarani god Abaasy yakut underworld gods Abandinus romano-celtic god Abarta irish god Abeguwo melansian rain goddess Abellio gallic tree god Abeona roman goddess of passage Abere melanisian goddess of evil Abgal arabian god Abhijit hindu goddess of fortune Abhijnaraja tibetan physician god Abhimukhi buddhist goddess Abhiyoga jain gods Abonba romano-celtic forest goddess Abonsam west african malicious god Abora polynesian supreme god Abowie west african god Abu sumerian vegetation god Abuk dinkan goddess of women and gardens Abundantia roman fertility goddess Anzu mesopotamian god of deep water Ac Yanto mayan god of white men Acacila peruvian weather god Acala buddhist goddess Acan mayan god of wine Acat mayan god of tattoo artists Acaviser etruscan goddess Acca Larentia roman mother goddess Acchupta jain goddess of learning Accasbel irish god of wine Acco greek goddess of evil Achiyalatopa zuni monster god Acolmitztli aztec god of the underworld Acolnahuacatl aztec god of the underworld Adad mesopotamian weather god Adamas gnostic christian creator god Adekagagwaa iroquois god Adeona roman goddess of passage Adhimukticarya buddhist goddess Adhimuktivasita buddhist goddess Adibuddha buddhist god Adidharma buddhist goddess -

Prayers Addressed to Lord Anjaneya in Sanskrit, Hindi, Tamil and Telugu

Prayers addressed to Lord Anjaneya in Sanskrit, Hindi, Tamil and Telugu Contents 1. Prayers addressed to Lord Anjaneya in Sanskrit, Hindi, Tamil and Telugu ........................................ 1 2. Anjaneya (Hanuman) Ashtotharam ........................................................................................................................ 2 3. Anjaneya Dandakam in Telugu................................................................................................................................. 4 4. Anjaneya Stotram ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 5. Anjaneya Stothra ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 6. Arul migu Anjaneyar , Hanuman thuthi-tamil ................................................................................................... 13 7. Bhajarang Baan.............................................................................................................................................................. 16 8. Ekadasa mukha Hanumath Kavacham ................................................................................................................. 19 9. Hanuman Chalisa .......................................................................................................................................................... 24 10. Hanuman ji ki aarthi ................................................................................................................................................... -

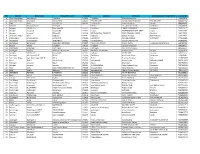

Sno District Block Name Village/CSC Name Pincode Location VLE Name Grampanchayat Village Name Contact No 1 Sant Kabir Nagar Semr

SNo District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Grampanchayat Village Name Contact No 1 Sant Kabir Nagar Semriyawan Tekensha 272125 Tekensha Mohammad Azam 789660973 2 Sant Kabir Nagar S K nagar3 MEHDAWAL 272271 PACHNEVARI ASHOK KUMAR MISHRA PACHNEVARI 840040772 3 Mau MAU RATANPURA 121705 Haldhar Pur Brijesh chauhan Ratohi 888069301 4 Varanasi Varanasi-NIELIT chollapur LANKA CIC_Manish Pandey Chollapur 896088439 5 Jaunpur JAUNPUR5 Ram nagar(R) 222137 Jamalapur LAXMI CHAURASIA Jamalapur 900559551 6 Jaunpur Jaunpur6 Jaunpur(R) 222139 Lapari MOHAMMAD AJMAL SHAH Lapari 904471787 7 Jaunpur Jaunpur1 Sirkoni(R) 222138 DR SHYAMLAL PRAJAPATI GYAN PRAKASH YADAV Gaddipur 964290095 8 Ambedkar Nagar Bhiti Naghara 224141 Naghara Gunjan Pandey Balal Paikauli 979214477 9 Maharajganj Maharajganj2 LAXMIPUR 273164 LAXMIPUR RAMESH KUMAR SURYAPUR 979416162 10 Gorakhpur Kempiyarganj Jangal Bihuli 273001 JUNGLE BIHULI SANJAY SRIVASTAVA 979456745 11 Gorakhpur Gorakhpur Jungle Beni Madho(U) 273007 Neaer Shiv Mandir Brijesh Kumar Jungle Beni Madho No.2 980792705 12 Deoria Bhatni Singhpur 274705 Singhpur Ugrasen Chaurasia 984188375 13 Chitrakoot Ramnagar Ram Nagar 245856 ramnagar Ravi Shanker Gupta 985632647 14 Azamgarh Koyalsa Molnapur Nathnpatti 246141 Molnapur Nathnpatti Ramesh Yadav Pasipur 993605118 15 Jaunpur JAUNPUR4 Barsathi(R) 222162 Ojhapur SUJIT PATEL Jarauta 994245307 16 Mirzapur Mirzapur-NIELIT Sikhar 231306 Pachranw Atul Kumar Singh pachranw 995695683 17 Sant Kabir Nagar Sant Kabir Nagar-NIELIT Belrai 451586 Belrai Pradeep Srivastav