Results from a Population-Based Mortality Survey in Ouaka Prefecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

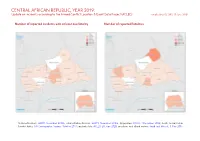

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Abyei Area: SSNBS, 1 December 2008; South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, October 2011; incident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 104 57 286 Conflict incidents by category 2 Strategic developments 71 0 0 Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 2 Battles 68 40 280 Protests 35 0 0 Methodology 3 Riots 19 4 4 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 2 2 3 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 299 103 573 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2010 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

1 FAITS ESSENTIELS • Regain De Tension À Gambo, Ouango Et Bema

République Centrafricaine : Région : Est, Bambari Rapport hebdo de la situation n o 32 (13 Aout 2017) Ce rapport a été produit par OCHA en collaboration avec les partenaires humanitaires. Il a été publié par le Sous-bureau OCHA Bambari et couvre la période du 7 au 13 Aout 2017. Sur le plan géographique, il couvre les préfectures de la Ouaka, Basse Kotto, Haute Kotto, Mbomou, Haut-Mbomou et Vakaga. FAITS ESSENTIELS • Regain de tension à Gambo, Ouango et Bema tous dans la préfecture de Mbomou : nécessité d’un renforcement de mécanisme de protection civile dans ces localités ; • Rupture en médicament au Centre de santé de Kembé face aux blessés de guerre enregistrés tous les jours dans cette structure sanitaire ; • Environ 77,59% de personnes sur 28351 habitants de Zémio se sont déplacées suite aux hostilités depuis le 28 juin. CONTEXTES SECURITAIRE ET HUMANITAIRE Haut-Mbomou La situation sécurité est demeurée fragile cette semaine avec la persistance des menaces d’incursion des groupes armés dans la ville. Ces menaces Le 10 août, un infirmier secouriste a été tué par des présumés sujets musulmans dans le quartier Ayem, dans le Sud-Ouest de la ville. Les circonstances de cette exécution restent imprécises. Cet incident illustre combien les défis de protection dans cette ville nécessitent un suivi rapproché. Mbomou Les affrontements de la ville de Bangassou sont en train de connaitre un glissement vers les autres sous-préfectures voisines telles Gambo, Ouango et Béma. En effet, depuis le 03 aout les heurts se sont produits entre les groupes armés protagonistes à Gambo, localité située à 75 km de Bangassou sur l’axe Bangassou-Kembé-Alindao-Bambari. -

NRC's Operations In

FACT SHEET January 2021 NRC’s operations in Central African Republic Ingrid Beauquis/NRCPhoto: Humanitarian overview NRC’s operation Since 2013, the Central African Republic (CAR) has While CAR is one of the most dangerous places for fallen victim to a conflict which has led to thousands humanitarians to work (with a 39 per cent increase in of people losing their lives and to massive population incidents against aid workers in 2020), NRC builds ac- movements. In February 2019, a peace agreement was ceptance to ensure that our support serves communities signed between the government and 14 armed groups. through integrated multi-sector assistance. We try to However, the situation gravely deteriorated in December focus on hard-to-reach areas where few other organisa- 2020 during the electoral process. A coalition of armed tions are present and aim to provide sustainable assis- groups, signatories of the peace agreement, launched tance. In 2020, our country office has operations in eight a series of attacks throughout the country and on the prefectures. NRC also advocates for the protection and outskirts of Bangui. rights of those affected by conflict, with a particular focus on housing, land, and property rights. This new conflict led to more than 100,000 newly dis- placed people, in addition to more than 600,000 inter- nally displaced people (IDPs) and 600,000 refugees. More than half of the population – 2.8 million – are in need of humanitarian assistance and protection. With a literacy rate of 37% and life expectancy at 53 years, CAR ranks second from the bottom on the Human Development Index. -

Fact Sheet #1, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2020 December 17, 2019

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2020 DECEMBER 17, 2019 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS BY SECTOR IN FY 2019 A GLANCE • 2020 HNO identifies 2.6 million people requiring humanitarian assistance 4% 3% 5% 20% • Number of aid worker injured in 2019 due 4.9 6% 6% to insecurity nearly doubles from 2018 • million 9% 19% More than 1.6 million people facing Crisis or worse levels of acute food insecurity Estimated Population 10% of CAR 18% UN – October 2019 Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (20%) Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (19%) Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (18%) HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Health (10%) FOR THE CAR RESPONSE IN FY 2019 Shelter & Settlements (9%) 2. 6 Protection (6%) Economic Recovery & Market Systems (6%) USAID/OFDA $48,618,731 Agriculture & Food Security (5%) million Nutrition (4%) Multipurpose Cash Assistance (3%) USAID/FFP $50,787,077 Estimated People in CAR Requiring Humanitarian USAID/FFP2 FUNDING State/PRM3 $44,883,653 Assistance BY MODALITY IN FY 2019 3% UN – October 2019 59% 22% 14% $144,289,461 U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (59%) 2% 1.6 Food Vouchers (22%) Local, Regional & International Food Procurement (14%) Complementary Services (3%) million Cash Transfers for Food (2%) Estimated People in CAR Facing Severe Levels of KEY DEVELOPMENTS Acute Food Insecurity IPC – June 2019 • The UN and humanitarian partners have identified 2.6 million people in need of humanitarian assistance in Central African Republic (CAR), representing a slight decrease from the 2.9 million people estimated to be in need as of early March. To respond to the 600,136 emergency needs of 1.6 million of the most vulnerable people throughout 2020, relief actors have appealed for $387.8 million from international donors. -

Central African Republic: DREF Operation N° MDRCF006 Violent Winds in Kembe, GLIDE N° VW-2009-000082- CAF Grimari, Zangba, Mboki, Olo 4 May, 2009 and Mbaïki

Central African Republic: DREF operation n° MDRCF006 Violent winds in Kembe, GLIDE n° VW-2009-000082- CAF Grimari, Zangba, Mboki, Olo 4 May, 2009 and Mbaïki The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of national societies to respond to disasters. CHF 81,924 (USD 72,125 or EUR 54,340) has been allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Central African Red Cross Society (CARCS) in delivering immediate assistance to some 1,230 beneficiaries. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: Since February 2009, heavy rains accompanied by violent winds and tornados have been hitting the Central African Republic (CAR) causing important damages. The disaster started in Bangui, the capital city, and extended to Berberati, Eastern CAR. Funds were allocated in February 2009 from the International Federation’s DREF to assist 278 vulnerable families identified in the affected localities. On April 2009 new localities including Kembe, Grimari, Zangba, Mboki and Obo in Southern CAR, and Mbaïki located 110 km from Bangui, have also been hit by violent winds. Field assessments conducted by the respective CARCS local committees revealed that over 10,500 people have been affected, with over 767 families, i.e. 3,835 people made homeless. Several houses have been partially or completely destroyed; cooking utensils and other household property have been damaged. -

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic

Security Sector Reform in the Central African Republic: Challenges and Priorities High-level dialogue on building support for key SSR priorities in the Central African Republic, 21-22 June 2016 Cover Photo: High-level dialogue on SSR in the CAR at the United Nations headquarters on 21 June 2016. Panellists in the center of the photograph from left to right: Adedeji Ebo, Chief, SSRU/OROLSI/DPKO; Jean Willybiro-Sako, Special Minister-Counsellor to the President of the Central African Republic for DDR/SSR and National Reconciliation; Miroslav Lajčák, Minister of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic; Joseph Yakété, Minister of Defence of Central African Republic; Mr. Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, Special Representative of the Secretary-General for the Central African Republic and Head of MINUSCA. Photo: Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of the Slovak Republic The report was produced by the Security Sector Reform Unit, Office of Rule of Law and Security Institutions, Department of Peacekeeping Operations, United Nations. © United Nations Security Sector Reform Unit, 2016 Map of the Central African Republic 14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° AmAm Timan Timan The boundaries and names shown and the designations é oukal used on this map do not implay official endorsement or CENTRAL AFRICAN A acceptance by the United Nations. t a SUDAN lou REPUBLIC m u B a a l O h a r r S h Birao e a l r B Al Fifi 'A 10 10 h r ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh k Garba Sarh Bahr Aou CENTRAL Ouanda AFRICAN Djallé REPUBLIC Doba BAMINGUI-BANGORAN Sam -

Key Points Situation Overview

Central African Republic Situation Report No. 55 | 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC (CAR) Situation Report No. 55 (as of 27 May 2015) This report is produced by OCHA CAR in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period between 12 and 26 May 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 10 June 2015. Key Points On 13 May, the IASC deactivated the Level 3/L3 Response, initially declared in December 2013. The mechanism aimed at scaling up the systemic response through surged capacities and strengthened humanitarian leadership, resulting in a doubling of humanitarian actors operating in country. On 27 May, the Emergency Relief Coordinator, Valerie Amos, designated Aurelien Agbénonci, Deputy Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Resident Coordinator in the CAR, as Humanitarian Coordinator (HC). A Deputy HC will be also be nominated. An international conference on CAR humanitarian needs, recovery and resilience- building was held in Brussels on 26 May under the auspices of the European Union. Preliminary reports tally pledges for humanitarian response at around US$138 million, with the exact proportion of fresh pledges yet to be determined. 426,240 2.7million 79% People in need of Unmet funding More than 300 children were released from IDPs in CAR armed groups following a UNICEF-facilitated assistance requirements agreement by the groups’ leaders to free all children in their ranks. 36,930 4.6 million US$131 million in Bangui Population of CAR pledged against The return and reinsertion process for IDPs at requirements of the Bangui M’poko site continues. As of 22 May $613 million 1,173 of the 4,319 households residing at the site have been registered in the 5th district of Bangui and will receive a one-time cash payment and return package. -

CAR: 3W Operational Presence in HAUTE KOTTO (As of May 2017)

CAR: 3W Operational Presence in HAUTE KOTTO ( As of May 2017 ) Organisations responding with By organisation type By cluster 23 emergency programs Food Security 9 National NGO 8 Protection 7 Health 5 UN 7 Shelter & NFI 5 Education 3 International NGO 6 Nutrition 3 WASH 3 Red Cross Movement 1 CCCM 2 Logistics 2 Government 1 Coordination 1 LCS 1 CCCM Education Food Security 2 partner 3 partners 9 partners Shelter & NFI Emergency Telecom. Logistics 5 partners 0 partner 2 partner Health LCS WASH 5 partners 1 partner 3 partners Nutrition Protection 3 partners 7 partners Is your data missing from this document? Return it to [email protected] and your data will be on the next version. Thanks for helping out! Updated: 11 June 2017. Source: Clusters and Partners Suggestions: [email protected]/ [email protected] . More information: http://car.humanitarianresponse.info/ Designations and geography used on these maps does not imply endorsement by the United Nations CAR: 3W Operational Presence in HAUTE KOTTO ( As of May 2017 ) Nord Soudan Nigéria 23 Partners Presence Tchad 8 NationalTchad NGO Sud Soudan Centrafrique 7 UN Cameroon 6 International NGO 1 Government Birao Republique Démocratique du Congo Congo 1 Red Cross Movement Nord Soudan Gabon Vakaga Tchad Ouanda-Djallé Sud Soudan IACE Ndélé Bamingui-Bangoran WHO ESPERANCE, IMC, INVISIBLE CHILDREN INVISIBLE CHILDREN IACE FAO, MAHDED WHO Ouadda INVISIBLE CHILDREN INVISIBLE CHILDREN Bamingui Haute-Kotto Yalinga Djéma Bakala OCHA Haut-Mbomou ECAC, IACE, IDEAL Bria ESPERANCE, NDA, WFP, MAHDED, OXFAM, FAO, ACMSEP, -

CAR CMP Population Moveme

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION Election-related displacements in CAR Cluster Protec�on République Centrafricaine As of 30 April 2021 Chari Dababa Guéra KEY FIGURES Refugee camp Number of CAR IDPs Mukjar As Salam - SD Logone-et-Chari Abtouyour Aboudéia !? Entry point Baguirmi newly displaced Kimi� Mayo-Sava Tulus Gereida Interna�onal boundaries Number of CAR returns Rehaid Albirdi Mayo-Lemié Abu Jabrah 11,148 15,728 Administra�ve boundaries level 2 Barh-Signaka Bahr-Azoum Diamaré SUDAN Total number of IDPs Total number of Um Dafoug due to electoral crisis IDPs returned during Mayo-Danay during April April Mayo-Kani CHAD Mayo-Boneye Birao Bahr-Köh Mayo-Binder Mont Illi Moyo Al Radoum Lac Léré Kabbia Tandjile Est Lac Iro Tandjile Ouest Total number of IDPs ! Aweil North 175,529 displaced due to crisis Mayo-Dallah Mandoul Oriental Ouanda-Djalle Aweil West La Pendé Lac Wey Dodjé La Nya Raja Belom Ndele Mayo-Rey Barh-Sara Aweil Centre NEWLY DISPLACED PERSONS BY ZONE Gondje ?! Kouh Ouest Monts de Lam 3,727 8,087 Ouadda SOUTH SUDAN Sous- Dosseye 1,914 Kabo Bamingui Prefecture # IDPs CAMEROON ?! ! Markounda ! prefecture ?! Batangafo 5,168!31 Kaga-Bandoro ! 168 Yalinga Ouham Kabo 8,087 Ngaoundaye Nangha ! ! Wau Vina ?! ! Ouham Markounda 1,914 Paoua Boguila 229 Bocaranga Nana Mbres Ouham-Pendé Koui 406 Borgop Koui ?! Bakassa Bria Djema TOuham-Pendéotal Bocaranga 366 !406 !366 Bossangoa Bakala Ippy ! Mbéré Bozoum Bouca Others* Others* 375 ?! 281 Bouar Mala Total 11,148 Ngam Baboua Dekoa Tambura ?! ! Bossemtele 2,154 Bambari Gado 273 Sibut Grimari -

KILLING WITHOUT CONSEQUENCE RIGHTS War Crimes, Crimes Against Humanity and the Special Criminal Court WATCH in the Central African Republic

HUMAN KILLING WITHOUT CONSEQUENCE RIGHTS War Crimes, Crimes Against Humanity and the Special Criminal Court WATCH in the Central African Republic Killing Without Consequence War Crimes, Crimes Against Humanity and the Special Criminal Court in the Central African Republic Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34938 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34938 Killing Without Consequence War Crimes, Crimes Against Humanity and the Special Criminal Court in the Central African Republic Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ......................................................................................................