Nirmali Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nirmali Assembly Bihar Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/BR-041-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-150-0 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 190 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-10 Constituency - (Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2015, 2014, 2010 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 11-18 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and -

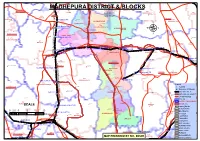

Madhepura District & Blocks

!. ÆR !. !. ÆR !. TRIVENIGANJ !. 045 CHHATAPUR Chakla Nirmali RS KOSI RIVER 044 KAMALPUR MSAUÆRPAUL DHEPURA DISTRICT & BLOCKS !. !. !. MADHUBA03N9I 042 TRIBENIGANJ (SC) 046 RANIGANJ PHULPARAS E PIPRA !. 049 N NARPATGANJ I KOSI RIVER !.BHARGAMA ARARIA SUPAL UL 043 Y KOSI RIVER A 081 SUPAUL BISHUNPUR SUNDAR !. W ARARIA GAMHARIA !. ALINAGAR L Bina Ekrna RS !. 047 GHANSHAMPUR I !. ÆR A SHANKERPUR RANIGANJ (SC) R SHANKARPUR GAMHARIA !. J N 072 Garh Baruari RS A ÆR SINGHESHWAR (SC) G KUMARKHAND !.KUMARKHAND P KIRATPUR JHAGRUA SINGHESHWAR !. NAUHATTA A !. T SINGHASWAR A !. DARBHANGA GHAILARH R !. µ P GHAILARH PATORI - ÆR !. SRINAGAR !. H PACHGACHHIA RS 079 !. !. GORA BAURAM R !.JAMALPUR 077 A G MAHISHI I 058 CHAMPANAGAR A !. !. KASBA R MADHEPURA A 073 ÆR BUDHMA RS S ÆR M!.URLIGANJ RS - BAIJNATHPUR RSMADHEPURA ÆR BANMAKHI DAURAM MADHEPURA RS ÆRMURLIGANJ RAMNAGAR PHARSAHÆR!.I A ÆR ÆRMurliganj RS !. ÆRBAIJNATHPATTI RS RAMNAGAR PHAÆRRSAHI S 059 Sarsi RS R MURLIGANJ BANMANKHI (SC) ÆR A SAHARSA RS !.SAHARSA H ÆR KAHARA NH !. -1 A 07 S MAHISHI !. Kirtiananagar RS SAUR BAZAR Aurahi RS ÆR!. 075 !. ÆR KRITYANAND NAGAR SAHARSA M MADHEPURA A KUSHESHWAR ASTHAN !. SN AHARSA PATARGHAT !. !. S 071 !. SONBARSA KACHARI RS I - BIHARIGANJ Barahara Kothi RS ÆR S ÆRBARHARA A GWALPARA !. 061 H Raghubanshnagar RS PURNIA DHAMDAHA A GOALPARA ÆR R !. DHAMDAHA S !. A !. - 074 BIHARIGÆRANJ B SIMRI BAKHTIPUR RS H SONBARSA (SC) BIHARIGANJ ÆR A !. 076 P SIMRI BAKHTIARPUR T Legend I A 140 SONBARSA KISHANGANJ !. SAMASTIPUR H !. !. TOWNS HASANPUR I !. ÆR R RAILWAY STATIONS A BANMA ITAHARI !. KOPARIA RS I BHAWANIPUR RAJDHAM RAILWAYLINES L KISHANGANJ !. !. SALKÆRHUA W FALKA NATIONAL HIGHWAYS A !. -

Report 1.13 Review of Literature

CONTENTS CHAPTERS PARTICULARS PAGE NO. Preface i-ii List of Tables iii-vi One Introduction 1-33 1.1 Background 1.2 Global View 1.3 Indian Scenario 1.4 Fisheries in Bihar 1.5 Kosi River System 1.6 Objectives 1.7 Hypothesis 1.8 Methodology 1.9 Research Design and Sampling Procedure 1.10 Research Procedure 1.11 Limitations of the Study 1.12 Layout of the Report 1.13 Review of Literature Two Profile of the Study Area 34-70 2.1 Section I: Profile of the State of Bihar 2.2 Land Holding Pattern 2.3 Flood Prone Areas 2.4 Section II : Profile of the Kosi River Basin 2.5 Siltation Problem of Kosi 2.6 Shifting Courses of Kosi 2.7 Water Logged Areas 2.8 Production potentiality 2.9 Section III : Profile of the sampled districts 2.10 Madhubani 2.11 Darbhanga 2.12 Samastipur 2.13 Khagaria 2.14 Supaul 2.15 Purnea 2.16 Section IV : Profile of Sampled Blocks 2.17 Section V: Water Reservoirs of the Sampled Area Three Economics of Fish Farming: 71-108 Results & Discussions 3.1 Background 3.2 Educational Status 3.3 Martial Status, Sex and Religion 3.4 Occupational Pattern 3.5 Size of Fishermen 3.6 Kinds of Family 3.7 Ownership of House 3.8 Sources of Income 3.9 Type of Houses 3.10 Details of Land 3.11 Cropping Pattern 3.12 Sources of Fish Production 3.13 Membership 3.14 Awareness of Jalkar Management Act 3.15 Cost of Fish Production 3.16 Pattern and Sources of Technical Assistance 3.17 Training for Fish Production 3.18 Awareness of the Assistance 3.19 Fishing Mechanism And Resources 3.20 Market System 3.21 Problems of Fish Production 3.22 Suggestions by the -

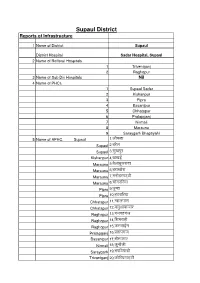

APHC & HSC List

Supaul District Reports of Infrastructure 1 Name of District Supaul District Hospital Sadar Hospital, Supaul 2 Name of Refferal Hospitals 1 Triveniganj 2 Raghopur 3 Name of Sub Div Hospitals Nil 4 Name of PHCs 1 Supaul Sadar 2 Kishanpur 3 Pipra 4 Basantpur 5 Chhatapur 6 Pratapganj 7 Nirmali 8 Marauna 9 Saraygarh Bhaptiyahi 5 Name of APHC. Supaul 1]ykSdgk Supaul 2]cjSy Supaul 3]lq[kiqj Kishanpur 4][k[kbZ Marauna 5]csyk/kqFkjkgk Marauna 6]cl[kksjk Marauna 7]euksgjiV~Vh Marauna 8]?kksxjfj;k Pipra 9]FkqEgk Pipra 10]gVofj;k Chhatapur 11]Xokyikjk Chhatapur 12]cyqvkcktkj Raghopur 13]xuirxat Raghopur 14]flejkgh Raghopur 15]djtkbZu Pratapganj 16]izrkixat Basantpur 17]Hkheuxj Nirmali 18]dqukSyh Saraygarh 19]HkifV;kgh Trivaniganj 20]dksfj;kiV~Vh APHC Upgrated in PHC izrkixat HkifV;kgh 6 Name of HSC 1]dfjgks Supaul 2]gjnh Supaul 3]pkS/kkjk Supaul 4]yksSdgk Supaul 5]Ck:vkjh iqjo Supaul 6]Ck:vkjhif’pe Supaul 7]Tkxriqj Supaul 8]Okh.kk Supaul 9]Ikjljek Supaul 10]Lqk[kiqj Supaul 11]flgs Supaul 12]cSjks Supaul 13]punSy Supaul 14]flrqgj Supaul 15]ykypUniV~Vh Supaul 16]clfoV~Vh Supaul 17]Ekygn Supaul 18pdyk fueZyh Supaul 19]cygk Kishanpur 20] dneiqjk Kishanpur 21] ueeuek Kishanpur 22] pkSgV~Vk Kishanpur 23] flafx;kou Kishanpur 24] lq[kklu Kishanpur 25] vUnkSyh Kishanpur 26] ljk;x< Kishanpur 27] eqyhZ Kishanpur 28] cuSfu;k Kishanpur 29] gluiqj Kishanpur 30] ukSvkok[kj Kishanpur 31] lqdekjiqj Kishanpur 32] ykyxat Kishanpur 33] [kkuiqj Marauna 34] tuknZuiqj Marauna 35] dejSy Marauna 36] xukSjk Marauna 37] eSugk Marauna 38] dnekgk Marauna 39] tkSogk Marauna -

Supaul District, Bihar State

1 भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका सुपौल स्जला, बिहार Ground Water Information Booklet Supaul District, Bihar State के न्द्रीय भमू िजल िो셍 ड Central Ground water Board Ministry of Water Resources जल संसाधन िंत्रालय (Govt. of India) (भारि सरकार) Mid-Eastern Region िध्य-पूर्वी क्षेत्र Patna पटना मसिंिर 2013 September 2013 GWIB | Supaul 1 2 GWIB | Supaul 2 3 PREPARED BY - Sri S. Sahu Sc. C GWIB | Supaul 3 4 CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Location, Area and Administrative Details 1.2 Basin/Sub-Basin and Drainage 1.3 Water use habits 1.4 Land use, Agriculture and Irrigation Practices 2.0 CLIMATE AND RAINFALL 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL 3.1 Geomorphology 3.2 Soil 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO 4.1 Water Bearing Formations 4.2 Depth to Water Level 4.3 Ground Water Quality 4.4 Ground Water Resources 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 5.1 Ground Water Development 5.2 Design and construction of Tube Wells 5.3 Water Conservation and Artificial Recharge 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND RELATED PROBLEMS: 7.0 MASS AWARENESS AND TRAINING PROGRAMME AREA NOTIFIED BY CENTRAL GROUND WATER AUTHORITY/ STATE GROUND 8.0 WATER AUTHORITY 9.0 RECOMMENDATION GWIB | Supaul 4 5 LIST OF TABLES Table No Title Table 1 Demographics of Supaul district, Bihar. Table 2 Agriculture and irrigation status in Supaul district. Table 3 Ground water quality of Supaul district. Table 4 Blockwise Dynamic Ground Water Resource (ham) of Supaul District (As on 31st March Table 5 Proposed Model of DTWs in Supaul district Table 6 Proposed slot openings for tube wells in Supaul district. -

EQ Damage Scenario.Pdf

DAMAGE SCENARIO UNDER HYPOTHETICAL RECURRENCE OF 1934 EARTHQUAKE INTENSITIES IN VARIOUS DISTRICTS IN BIHAR Authored by: Dr. Anand S. Arya, FNA, FNAE Professor Emeritus, Deptt. of Earthquake Engg., I.I.T. Roorkee Former National Seismic Advisor, MHA, New Delhi Padmashree awarded by the President, 2002 Member BSDMA, Bihar Assisted by: Barun Kant Mishra PS to Member BSDMA, Bihar i Vice Chairman Bihar State Disaster Management Authority Government of Bihar FOREWORD Earthquake is a natural hazard that can neither be prevented nor predicted. It is generated by the process going on inside the earth, resulting in the movement of tectonic plates. It has been seen that wherever earthquake occurs, it occurs again and again. It is quite probable that an earthquake having the intensity similar to 1934 Bihar-Nepal earthquake may replicate again. Given the extent of urbanization and the pattern of development in the last several decades, the repeat of 1934 in future will be catastrophic in view of the increased population and the vulnerable assets. Prof A.S.Arya, member, BSDMA has carried out a detailed analysis keeping in view the possible damage scenario under a hypothetical event, having intensity similar to 1934 earthquake. Census of India 2011 has been used for the population and housing data, while the revised seismic zoning map of India is the basis for the maximum possible earthquake intensity in various blocks of Bihar. Probable loss of human lives, probable number of housing, which will need reconstruction, or retrofitting has been computed for various districts and the blocks within the districts. The following grim picture of losses has emerged for the state of Bihar. -

Supaul Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE SUPAUL INTRODUCTION Supaul is one of the thirty-eight districts of Bihar. It is a part of Kosi division. Supaul was accorded the status of a sub-division in 1862. Supaul district was carved out from the erstwhile Saharsa district on 14th March, 1991. Supaul district is bounded by Nepal in the north, Madhepura and Saharsa districts in the south, Araria district in the east and Madhubani district in the west. Supaul district has an international border with Nepal. The river flowing through Supaul district is Kosi. River Kosi is regularly in spate, hence it is considered as the “sorrow of Bihar’’. The major distributaries of Kosi flowing through Supaul are Tilyuga Chhaimra, Kali, Tilawe, Bhenga, Mirchaiya and Sursar. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Supaul has a rich history. This district had been a part of Mithilanchal since the Vedic age. The area has been referred to as Matsya Kshetra-the fishery area, in Hindu mythology. The two oldest democracies namely Angutaran and Apadnigam known to have existed during the Buddhist era, were present in the area which comprises of today’s Supaul district. Kunauli is a small town of Supaul district on the border of Nepal’s Saptari district. The name Kunauli is derived from the Mauryan emperor Ashoka's son, Kunal who once ruled this place. The western embankment bank of Kosi runs through Kunauli. With the establishment of Magadh empire, Kosi river basin became a part of Teer Bhukti and Pondravardhan Bhukti. Buddhism existed and flourished here for about 200 years during the regime of Pala dynasty. During the ancient period, Supaul area was ruled by the Nanda Vansha, Maurya, Sungas and Mithila dynasty. -

Bihar Building New Avenues of Progress Bihar

BIHAR BUILDING NEW AVENUES OF PROGRESS BIHAR Uttar Pradesh Jharkhand West Bengal In the State of Bihar, a popular destination for spiritual tourists from all over the world, the length of National Highways has been doubled in the past four years. Till 2014, the length of National Highways was 4,447 km. In 2018, the length of National Highways has reached 8,898 km. The number of National Highways have been increased to 102 in 2018. Road development works worth Rs. 20,000 Cr are progressing rapidly. In the next few years, investments worth Rs. 60,000 Cr will be made towards transforming the road sector in Bihar, and creating new socio-economic opportunities for the people. “When a network of good roads is created, the economy of the country also picks up pace. Roads are veins and arteries of the nation, which help to transform the pace of development and ensure that prosperity reaches the farthest corners of our nation.” NARENDRA MODI Prime Minister “In the past four years, we have expanded the length of Indian National Highways network to 1,26,350 km. The highway sector in the country has seen a 20% growth between 2014 and 2018. Tourist destinations have come closer. Border, tribal and backward areas are being connected seamlessly. Multimodal integration through road, rail and port connectivity is creating socio economic growth and new opportunities for the people. In the coming years, we have planned projects with investments worth over Rs 6 lakh crore, to further expand the world’s second largest road network.” NITIN GADKARI Union Minister, -

Supaul Supaul

Prepared by: Presented to VIVEK SHARAN, District Magistrate, District Facilitator, Supaul Supaul INDEX Sl Headings Page No No 1 Background 3 2 Historical Perspective 3 3 Geography 4 o Border Area Perspective 4 o Water Resources 5 o Soil 5 o Agro-climatic Conditions 5 o Climate 5 4 Connetivity 6 5 Political & Administration 6 6 Panchayati Raj 8 7 Human Resource 8 8 Demography 9 10 Citizens’Profile 11 11 Area Profile 12 12 Sex Ratio 14 13 Education 17 14 Health 19 15 Women & Child Development 21 16 Sanitation 22 17 Banking 23 18 Development Indicators 24 19 Basic Amenities 25 20 References 26 Vivek Sharan, District Facilitator, Supaul Page 2 BACKGROUND The District of Supaul had been a part of Mithilanchal since the Vedic period. The area has been referred to as the fishery area (Matsya kshetra) in the Hindu mythology. The two oldest democracies namely Angutaran and Aapanigam are known for their existence in the Buddhist era, which comprises of today’s areas of district Supaul. It has a long history of its existence and transformation. Historical Perspective During the by-gone era of Buddhism, area comprising Supaul of present time was famously known for two independent states of Angutaran & Apadnigam. It is mentioned in the Buddhism scripture of Majhim Nikay & Thergatha. Erstwhile Apadnigam area was spread from Bakhtiyarpur to Supaul comprising hundred of markets. Mahatma Buddha stayed in the area for one month. During Palwansh, the area witnessed spread of Buddhism for nearly 200 years whose remainant could be seen even today in idols of ancient temples and folk songs. -

Supaul District: List of Shortlisted Candidates for Uddeepika

Supaul District: List of Shortlisted Candidates for Uddeepika S .No. Application No. Panchayat Name Block Name Candidate Name Father's/ Husband Name Correspondence Address Date Of Birth Ctageory Permanent Address DD/IPO Number Percentage Of Marks 1 27 Amha Pipra PUJA KUMARI RAMCHANDRA SAH VILL- TETRAHI, PO- AMHA, PS- PIPRA 15-Sep-91 BC Same as above 34H 283244 62.00 2 91 Babhangama Triveniganj MANJU KUMARI SUNIL KUMAR VILL+PO- MALAHNAMA, VIA- TRIVENIGANJ, PINCODE- 852139 21-May-87 BC Same as above 34H 283242 63.00 C/O- RAMANAND JHA, VILL- MALHAD, TOLA, MALHAD, PO- SUPAUL, 3 54 Bairiya Supaul MALA KUMARI ROSHAN KUMAR JHA PINCODE- 852131 07-Feb-90 GEN Same as above 34H 783330 57.00 CHANDRAKISHORE 4 52 Bairo Supaul RITU KUMARI KUMAR VILL+PO- BAIRO, VIA- NAWHATTA, PS- SUPAUL, PINCODE- 852123 15-Feb-91 EBC Same as above 34H 286984 68.00 RAMENDRA NARAYAN 5 44 Balwa Supaul VANDANA KUMARI YADAV VILL- PIPRAHARI, PO- PIPRAKHURD, VIA- SUPAUL, PINCODE- 852131 26-Dec-91 BC Same as above 34H 287079 65.00 VILL+PO- BAYASI, VIA- KARJAIEN BAJAR, WARD NO-07, PINCODE- 6 22 Bayasi Raghopur PUNAM KUMARI HALDHAR PRASAD YADAV 852215 01-Nov-87 BC Same as above 34H 759397 57.00 7 33 Belhi Marauna PARVATI DEVI RAJESH KUMAR VILL+PO- BELHI, VIA- NIRMALI 30-Mar-90 EBC Same as above 34H 256372 59.00 VILL+PO- BHAWANIPUR (S), WARD NO-6, PS- PRATAPGANJ, 8 56 Bhawanipur South Pratapganj KALPANA KUMARI BABLU KUMAR BHAGAT PINCODE- 852125 10-Feb-85 BC Same as above 12G 495994-98 64.00 9 36 Berhara Marauna KUMAR SANGITA ANIL KUMAR MANDAL VILL- PANCHGACHIYA, PO- MANOHAR PATTI, -

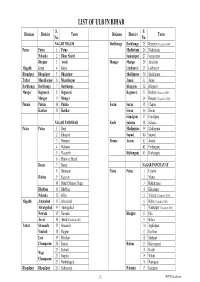

List of Ulb in Bihar

LIST OF ULB IN BIHAR S. S. Division District Town Division District Town No. No. NAGAR NIGAM Darbhanga Darbhanga 25 Benipur (Created in 2009) Patna Patna 1 Patna Madhubani 26 Madhubani Nalanda 2 Bihar Sharif Samastipur 27 Samastipur Bhojpur 3 Arrah Munger Munger 28 Jamalpur Magadh Gaya 4 Gaya Lakhisarai 29 Lakhisarai Bhagalpur Bhagalpur 5 Bhagalpur Sheikhpura 30 Sheikhpura Tirhut Muzaffarpur 6 Muzaffarpur Jamui 31 Jamui Darbhanga Darbhanga 7 Darbhanga Khagaria 32 Khagaria Munger Begusarai 8 Begusarai Begusarai 33 Beehat (Created in 2009) Munger 9 Munger 34 Barauni (Created in 2009) Purnia Purnia 10 Purnia Saran Saran 35 Chapra Katihar 11 Katihar Siwan 36 Siwan Gopalganj 37 Gopalganj NAGAR PARISHAD Koshi Saharsa 38 Saharsa Patna Patna 1 Barh Madhepura 39 Madhepura 2 Khagaul Supaul 40 Supaul 3 Danapur Purnia Araria 41 Araria 4 Mokama 42 Forbesganj 5 Masaurhi Kishanganj 43 Kishanganj 6 Phulwari Sharif Buxur 7 Buxur NAGAR PANCHAYAT 8 Dumraon Patna Patna 1 Fatwah Rohtas 9 Sasaram 2 Maner 10 Dehri Dalmiya Nagar 3 Bakhtiarpur Bhabhua 11 Bhabhua 4 Khusrupur Nalanda 12 Hilsa 5 Vikram (Created in 2009) Magadh Jehanabad 13 Jehanabad 6 Bihta (Created in 2009) Aurangabad 14 Aurangabad 7 Naubatpur (Created in 2009) Nawada 15 Nawada Bhojpur 8 Piro Arval 16 Arval (Created in 2009) 9 Behea Tirhut Sitamarhi 17 Sitamarhi 10 Jagdishpur Vaishali 18 Hajipur 11 Koilwar East 19 Motihari 12 Shahpur Champaran 20 Raxaul Rohtas 13 Bikramganj 21 Bettiah 14 Koath West 22 Bagaha 15 Nokha Champaran 23 Narkatiaganj 16 Nasriganj Bhagalpur Bhagalpur 24 Sultanganj Nalanda 17 Islampur 13 RCUES, Lucknow S. S. Division District Town Division District Town No. -

Answered On:27.07.2000 Railway Projects Sanctioned in Samastipur Division Dinesh Chandra Yadav

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA RAILWAYS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:839 ANSWERED ON:27.07.2000 RAILWAY PROJECTS SANCTIONED IN SAMASTIPUR DIVISION DINESH CHANDRA YADAV Will the Minister of RAILWAYS be pleased to state: (a) the details of the surveys sanctioned in Samastipur Railway Division under North- East Railway during the last three years; (b) the present status of these projects: and (c) the details of on-going railway project under Samastipur Railway Division ? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS (SHRI DIGVIJAY SINGH) (a) and (b):The position of sanctioned surveys in Samastipur Division is as under: S.No. Name of the project & Length Present Status 1. Sakari-Jhanjharpur-Laukaha Bazar (62.32 Km) Due to unremunerative nature of the project and acute constraint of resources, it has not been found possible to consider taking up this project. 2. Sakari-Nirmali (52.32 KM) Due to unremunerative nature of the project and acute constraint of resources, it has not been found possible to consider taking up this project 3. (a) Saharasa-Katihar (1126.11 Km) Due to unremunerative nature of the (b)Saharsa-Purnea (including Banmankhi, project and acute constraint of resources Bihariganj) 125.93 km it has not been found possible to consider taking up this project. 4. Hassanpur-Barauni (43.00 km) Due to unremunerative nature of the project and acute constraint of resources, it has not been found possible to consider taking up this project. 5. Kursela-Saharsa (91.10 km) Due to unremunerative nature of the project and acute constraint of resources, it has not been found possible to consider taking up this project.