The Use of Copyright Laws to Prevent the Importation of Genuine Goods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pcbs : 465 in 1 Babystar PCB

PCBs : 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB 465 Games in 1 BabyStar PCB Rating: Not Rated Yet Price: Sales price: $274.95 Discount: Ask a question about this product Description 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB ***ATX Power Supply with P4 connector required for operation*** JAMMA ready arcade system containing 465 vertical ready to play games. Choose from classics like Ms. Pac man, Donkey Kong, and Frogger to great shooters like 19XX, Strikers 1945 II, and Varth! The game selection menu is easy to understand and navigate. To select a game, scroll through the list and press your button to select. At anytime during the active game aplayer can return back to main game selection menu by holding in the start button for 3 seconds. This sytem runs on a stable flash drive. No hard drive to ever fail! Supports Vertically mounted monitors only. Universal JAMMA Connector. User Friendly Game Selection Screen. P4 Motherboard using genuine Intel Processor and Card Flash memory creates a faster/more stable system! User Adjustable Game Options (Game Dip Switch Settings; Number of Lives, Difficulty, etc). Supports 1-4 Player Games (players 3 & 4 via linking - kit included). Supports two-channel audio (Stereo Sound). Supports CGA Standard Arcade Monitor (15kHz). Supports Upright Cabinets (will not flip screen for cocktails). Enable One Game (for a dedicated machine if desired) or All Games. Enable/Disable Individual Game Categories From Showing. Delete/Undelete Each Game. Set Coin/Credit Ratio of All Games with One Setting. Supports a Coin Counter. System Specifications: JAMMA Controller/Interface PCB. -

Table 1 : Japanese Investment Projects Submitted to BOI

Table 1 : Japanese Investment Projects Submitted to BOI Unit: Million Baht 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Net Application No. of projects 316 340 387 335 330 324 Total Investment 106,374.1 101,855.6 175,314.2 110,477.1 149,071.9 102,994.3 Total Registered Capital 14,385.8 8,411.9 14,109.6 13,594.5 25,438.8 18,336.8 - Japanese 12,438.6 6,132.2 11,998.0 11,658.8 19,606.7 16,118.4 - Thai 1,386.1 1,843.3 1,462.8 1,606.2 3,414.0 1,979.5 Application Approved No. of projects 260 350 354 353 330 324 Total Investment 97,596.9 125,931.8 171,796.4 115,199.7 164,323.2 106,155.1 Total Registered Capital 15,913.4 15,381.4 14,141.5 21,032.8 32,060.1 24,147.5 - Japanese 14,386.4 12,872.2 12,693.5 15,180.7 23,360.0 22,191.8 - Thai 1,128.6 2,129.9 1,176.1 5,740.4 6,344.1 1,477.4 Note: 1) Japanese investment projects refer to projects with Japanese capital of at least 10%. International Affairs Bureau., BOI As of January 15, 2009 Table 2 : Japanese Projects Classified by Investment Size Unit: Million Baht Investment Size 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 (million Baht) No. of Investment No. of Investment No. of Investment No. of Investment No. of Investment No. of Investment Projects Projects Projects Projects Projects Projects Net Application <50 104 2,375.0 120 2,657.5 129 2,842.9 146 2,921.3 120 2,146.7 134 2,574.1 50-99 52 3,634.9 44 3,004.2 61 4,580.9 31 2,067.4 56 3,972.7 41 2,908.2 100-499 128 31,961.7 140 33,343.6 151 38,227.8 113 28,803.5 109 27,070.4 108 27,433.0 500-999 11 7,098.6 17 12,180.8 26 18,731.6 21 14,722.3 22 14,635.8 21 13,544.5 >1,000 -

Monthly Trading Value of Most Active Stocks (Mar.2012) 1St Section

Monthly Trading Value of Most Active Stocks (Mar.2012) 1st Section Rank Code Issue Trading Value \ mil. 1 7203 TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION 752,067 2 8306 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group,Inc. 730,107 3 3632 Gree,Inc. 502,599 4 8604 Nomura Holdings, Inc. 499,738 5 8316 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group,Inc. 484,590 6 8411 Mizuho Financial Group,Inc. 479,077 7 7267 HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 463,849 8 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 461,233 9 6954 FANUC CORPORATION 446,135 10 7751 CANON INC. 397,098 11 6301 KOMATSU LTD. 395,772 12 7261 Mazda Motor Corporation 382,125 13 9984 SOFTBANK CORP. 376,578 14 6753 Sharp Corporation 375,316 15 7201 NISSAN MOTOR CO.,LTD. 360,947 16 8058 Mitsubishi Corporation 347,340 17 6758 SONY CORPORATION 340,209 18 9983 FAST RETAILING CO.,LTD. 322,905 19 2432 DeNA Co.,Ltd. 314,045 20 6502 TOSHIBA CORPORATION 309,996 21 8031 MITSUI & CO.,LTD. 301,066 22 4502 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited 269,567 23 9432 NIPPON TELEGRAPH AND TELEPHONE CORPORATION 241,388 24 9433 KDDI CORPORATION 221,661 25 9437 NTT DOCOMO,INC. 215,232 26 8001 ITOCHU Corporation 215,078 27 6752 Panasonic Corporation 214,525 28 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 214,082 29 8801 Mitsui Fudosan Co.,Ltd. 212,776 30 8802 Mitsubishi Estate Company,Limited 210,943 31 9104 Mitsui O.S.K.Lines,Ltd. 199,642 32 6762 TDK Corporation 199,253 33 8035 Tokyo Electron Limited 199,065 34 8002 Marubeni Corporation 198,306 35 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 192,983 36 5411 JFE Holdings,Inc. -

Boxing Week/ January 2020

It has been wonderful to see so many of you over the past year in our new location. We really appreciate and thank you for your support. May you enjoy your time with friends and family. We look forward to seeing you all again in 2020! Happy Holidays from all your friends at Beau! Monday Dec. 23rd – 8:30-5pm Tuesday Dec. 24th – 8:30-2pm Dec 25th and 26th – Closed Friday Dec. 27th – 8:30-5pm Saturday Dec. 28th – 10am-2pm Monday Dec. 30th – 8:30-5pm Tuesday Dec. 31st – 8:30-2pm Happy New Year! January 1st 2020 – Closed Jan 2nd – Back to regular hours. Beau Newsletter - Boxing Week/ January 2020 Boxing Week Specials! • Come On In and Save on Digital Cameras, Sigma Lenses, Rode Microphones, Bags, Film, Filters, Inkjet Paper and More • See Inside for Details... DON’T MISS OUT! SALE ENDS JANUARY 9, 2020 See next page for S AV E + BONUS Premium Accessory Kit an even bigger (LP-E6N+1000SR bag + RC Strap LENS SAVINGS $700† + 128GB card ($330 value) discount until Dec. 27th... 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 EF 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6L IS II USM $3,219/$2,429 SAVE $790† 2 EF 24-70mm f/2.8L II USM $2,779/$2,149 SAVE $630† 3 EF 16-35mm f/4L IS USM EOS 5D MARK IV 24-105 KIT $5,149 / $4,449† $1,609/$1,199 SAVE $410† EOS 5D MARK IV 24-70 F4 KIT $4,949 / $4,249† 4 EF 16-35mm f/2.8L III USM EOS 5D MARK IV BODY $3,999 / $3,299† $2,849/$2,449 SAVE $400† 5 EF 24-70mm f/4L IS USM $1,469/$1,099 SAVE $370† S AV E + BONUS Premium Accessory Kit (LP-E6N+1000SR bag + RC Strap 6 EF 70-200mm f/2.8L IS III USM $500† + 128GB card ($330 value) $2,799/$2,449 SAVE $350† 7 EF-S 55-250mm f/4-5.6 IS STM $399/$229 SAVE $170† ADD A LENS WITH DSLR PURCHASE 8 9 10 8 EF-S 10-18mm f/4.5-5.6 IS STM $439/$269 SAVE $170† 9 EF 40mm f/2.8 STM $299/$169 SAVE $130† EOS 6D MARK II 24-105 KIT $3,149 / $2,649† 10 EF 50mm f/1.8 STM EOS 6D MARK II BODY $1,999 / $1,499† $189/$159 SAVE $30† All prices valid December 24, 2019 - January 9, 2020. -

Hugostudio List of Available Camera Covers

Exakta VX 1000 W/ P4 Finder Hugostudio List of Exakta VX 500 W/ H3.3 Finder Available Camera Covers Exakta VX IIa V1-V4 W/ P2.2 Finder Exakta VX IIa V5-V7-V8 _P3.3 Finder (1960) Exakta VX IIa V6 W/ H3 SLR Exakta VX IIb W/ P3 Asahiflex IIb Exakta VX IIb W/ P4 Finder Canon A-1 Exakta Varex VX V1 - V2 Canon AE-1 Exakta-Varex VX IIa V1-V4 Canon AE-1 Program Exakta Varex VX V4 V5 Canon AV-1 Exakta Varex VX W/ Finder P1 Canon EF Fujica AX-3 Canon EX Auto Fujica AZ-1 Canon F-1 Pic Req* Fujica ST 601 Canon F-1n (New) pic Req* Fujica ST 701 Canon FT QL Fujica ST 801 Canon FTb QL Fujica ST 901 Canon FTb n QL Kodak Reflex III Canon Power Winder A Kodak Reflex IV Canon TL-QL Kodak REflex S Canon TX Konica FT-1 Canonflex Konica Autoreflex T3 Chinon Memotron Konica Autoreflex T4 Contax 137 MA Konica Autoreflex TC Contax 137 MD Leica R3 Contax 139 Quartz Leica R4 Contax Motor Drive W6 Leica Motor Winder R4 Contax RTS Leicaflex SL Contax RTS II Mamiya ZE-2 Quartz Contax139 Quartz Winder Minolta Auto Winder D Edixa Reflex D Minolta Auto Winder G Exa 500 Minolta Motor Drive 1 Exa I, Ia, Ib Minolta SR 7 Exa II Minolta SRT 100 Exa IIa Minolta SRT 101 Exa Type 6 Minolta SRT 202 Exa VX 200 Minolta X370 Exa Version 2 to 5 Minolta X370s Exa Version 6 Minolta X570 Exa Version I Minolta X700 Exakta 500 Minolta XD 11, XD 5, XD 7, XD Exakta Finder H3 Minolta XE-7 XE-5 Exakta Finder: prism P2 Minolta XG-1 Exakta Finder: prism P3 Minolta XG 9 Exakta Finder: prism P4 Minolta XG-M Exakta Kine Minolta XG7, XG-E Exakta Meter Finder Minolta XM Exakta RTL1000 Miranda AII -

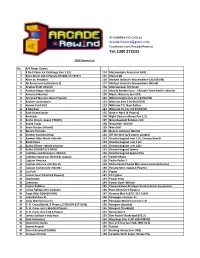

Arcade Rewind 3500 Games List 190818.Xlsx

ArcadeRewind.com.au [email protected] Facebook.com/ArcadeRewind Tel: 1300 272233 3500 Games List No. 3/4 Player Games 1 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 114 Metamorphic Force (ver EAA) 2 Alien Storm (US,3 Players,FD1094 317-0147) 115 Mexico 86 3 Alien vs. Predator 116 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (US,FD1094) 4 All American Football (rev E) 117 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (World) 5 Arabian Fight (World) 118 Minesweeper (4-Player) 6 Arabian Magic <World> 119 Muscle Bomber Duo - Ultimate Team Battle <World> 7 Armored Warriors 120 Mystic Warriors (ver EAA) 8 Armored Warriors (Euro Phoenix) 121 NBA Hangtime (rev L1.1 04/16/96) 9 Asylum <prototype> 122 NBA Jam (rev 3.01 04/07/93) 10 Atomic Punk (US) 123 NBA Jam T.E. Nani Edition 11 B.Rap Boys 124 NBA Jam TE (rev 4.0 03/23/94) 12 Back Street Soccer 125 Neck-n-Neck (4 Players) 13 Barricade 126 Night Slashers (Korea Rev 1.3) 14 Battle Circuit <Japan 970319> 127 Ninja Baseball Batman <US> 15 Battle Toads 128 Ninja Kids <World> 16 Beast Busters (World) 129 Nitro Ball 17 Blazing Tornado 130 Numan Athletics (World) 18 Bomber Lord (bootleg) 131 Off the Wall (2/3-player upright) 19 Bomber Man World <World> 132 Oriental Legend <ver.112, Chinese Board> 20 Brute Force 133 Oriental Legend <ver.112> 21 Bucky O'Hare <World version> 134 Oriental Legend <ver.126> 22 Bullet (FD1094 317-0041) 135 Oriental Legend Special 23 Cadillacs and Dinosaurs <World> 136 Oriental Legend Special Plus 24 Cadillacs Kyouryuu-Shinseiki <Japan> 137 Paddle Mania 25 Captain America 138 Pasha Pasha 2 26 Captain America -

Dimensional Investment Group

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2008-04-29 | Period of Report: 2008-02-29 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-08-027772 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC/ Business Address 1299 OCEAN AVE CIK:861929| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 1130 11TH FLOOR Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-06067 | Film No.: 08784216 SANTA MONICA CA 90401 2133958005 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 811-6067 DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Catherine L. Newell, Esquire, Vice President and Secretary Dimensional Investment Group Inc., 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 310-395-8005 Date of fiscal year end: November 30 Date of reporting period: February 29, 2008 ITEM 1. SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS. Dimensional Investment Group Inc. Form N-Q February 29, 2008 (Unaudited) Table of Contents Definitions of Abbreviations and Footnotes Schedules of Investments U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio II U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio III LWAS/DFA U.S. High Book to Market Portfolio DFA International Value Portfolio Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. -

Features of Mamiya RB 67

INSTRUCTIONS Congratulations on your pur chase of a Mamiya RB67 camera. Reading this manual carefully before· hand will ensure correct camera opera· tion and eliminate any possibility of malfunction. The Mamiya RB67 camera is part of a 'unique camera system, developed by the Mamiya Camera Company, the re· cognized world leader in large format photography. It takes its place alongside the famous Mamiya C Professional and the Mamiya Press cameras. The versatility of the Mamiya RB67, embodying fine performance and various capabilities, results in a large format camera that meets and satisfies all the requirements of the advanced amateur as weil as the professional photographer. Its interlocking use of many Mamiya Press camera accessories further widens its range of photographic application. • Special Pointers in Using the Mamiya RB 67 Under any of the following conditions the cameras safety interlock mechanism will engage. This may seem to be a ca me ra malfunction. A few of these conditions are listed below. The page in the instruction manual covering these situations is indicated in parenthesis. Condition: Shutter release button will not release. 1. When the mirror is up: Press the shutter cocking lever (pg. 12). 2 . When the dark slide is not pulled out: Pull out the dark slide (pg. 18). 3 . When the shutter release button is locked: Turn the shutter release lock ring counterclockwise (pg. 12). 4 . When the revolving adapter is not turned fully to the click stop position: Turn the revolving adapter a full 90° until it clicks and stops (pg. 14). 5 . When the slide lock is stopped halfway:. -

) ) Items Listed on the Attached Multnomah County Sheriff's Office

BEFORE THE BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS FORMULTNOMAH COUNTY, OREGON Acknowledgment of Unclaimed ) ORDER , Property and Authorization of ) 98-24 Transfer for Sale or Disposal ) WHEREAS, the Multnomah County Sheriff's Office has certain property, including money, in its possession, the ownership of which is unknown and which has been unclaimed for thirty days after the property came into its possession; and WHEREAS, Multnomah County Code Chapter 7.70.100 directs the Sheriffs Office to report the unclaimed property to the Board of Commissioners and to request authorization to dispose of it as provided in the Code; and WHEREAS, in lieu of a sale of the property under Multnomah County Code Chapter 7.70.150 to 7.70.300, the Multnomah County Sheriff's Office, with the approval of the Board of Commissioners, may transfer any portion of the unclaimed property to the County for use by the County; now therefore IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners acknowledges the unclaimed property and authorizes the transfer of the items listed on the attached Multnomah County Sheriff's Office Found/Unclaimed Property For Disposal, List 98-1, to the Department of Environmental Services for sale or disposal as provided in Multnomah County Code. 2nd day of April, 1998. BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS FOR MULTNOMAH COUNTY, OREGON I REVIEWED: I TOM SPONSLER, COUNTY COUNSEI MULTNOMAH COUNTY, OREGON .. MULTNOMAH COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE FOUND/UNCLAIMED PROPERTY FOR DISPOSAL LIST - 98-1 FILE NUMBER PROPERTY DESCRIPTION DISPOSITION 91-273 Motorola cell phone, #472CPLC949 Sale 91-5110 Sony car stereo, #112057 Sale 91-7818 Six Nintendo videos Sale 91-7913 Canon camera, #1716949 Sale XLR camer/2X telephoto w/elec. -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

MAMIYA M645 From

REPORT ON THE MAMIYA M645 from Mamiya M645: 15 on 120 in a Compact SLR JANUARY 1976 BELL &HOWELL/MAMIYA COMPANY Since the "semi-120" format is vantage of this "oddball" size is the M645's most evident distin that its negative area is 2.7X guishing feature, let's discuss it a larger than 35mm , providing bet git. This format dates back to (at ter picture quality, and, at the modern least) the 20 's, and was arrived at same time, it's smaller than 6 x 7cm by simply halving the original 6 x or 2 'j,, -in. square, resulting in a 9cm (2'j" x 3'j,,-in.) format ob smaller, more portable camera. tained with 120 roll film . Perhaps When you consider tha the 2'j" x the most notable camera to es 2 '14 format is most often cropped pouse these film dimensions was in printing, 4.5 x 6cm offers a the Dresden-produced Ermanox, comparably large usable nega a "candid camera" of the 20's, tive area in a more compact while the format's latest expo package, and you have the added nents (prior to the M645) were benefit of more shots per roll (15 newest cameras, lenses & important accessories both folding roll-film cameras instead of 12 per roll of 120 film). with coupled rangefinders, the Among the disadvantages of this Zeiss Super Ikonta A and Konica format: there's presently no slide- MAMIYA M645: 15 ON 120 IN A COMPACT SLR Mamiya M645: What's New 80mm f/2.8 Mamiya·Sekor C lens MANUFACTURER'S SPECIFI At a Glance ~~","""--- has three·lug bayonet mount CATIONS: Mamiya M645 me dium-Iormat 120 roll-film single lens reflex camera. -

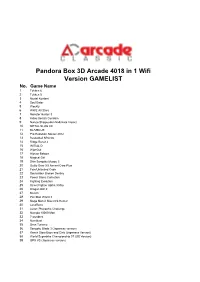

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech