Applying Sufficiency Economy Philosophy and Sustainable Approaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Report on Situation of Home-Based Workers' Groups In

Study Report on Situation of Home-based Workers’ Groups in Urban Areas and Target Groups under the Inclusive Urban Planning Project Submitted to Homenet South Asia Compiled by Foundation for Labour and Employment Promotion October 2010 Study Report on Home-based Workers’ Groups in Urban Areas October 2010 1 1. Background Home-based workers (HBWs)1 are generally poor, receiving low wages or income and working long hours, thus earning inadequate income to support their household expenses. These workers live in slum communities2 scattered in urban or suburban areas. As a result, it is difficult for them to organize. Their presence is virtually non-existent, not known or socially recognized, and not economically valued as a group of workers that contribute to the urban and national economy. Thus these HBWs have no participatory role in their local or community development planning. The Inclusive Urban Planning (IUP) Project is developed to build up and strengthen the capacity of HBW’s groups by supporting their organization in the form of membership- based organizations (MBOs)3. MBOs will act as representatives of the HBWs in presenting their problems and needs to government agencies so that these workers will be given a chance to participate in the urban planning process, which is suitable for their needs. This five-year Project (2009-2013) is carried out by Homenet Thailand and its collaborating non-governmental organizations. Homenet Thailand (HNT) was established in 1992 and registered as the Foundation for Labor and Employment Promotion in 2003. The Project’s major operation areas are Bangkok, Chiang Rai and Khon Kaen provinces. -

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Community Development On

Proceeding of The 8th International Conference on Integration of Science and Technology for Sustainable Development (8th ICIST) in November 19-22, 2019 at Huiyuan International Hotel, Jingde, Anhui Province, P.R. China. Evaluation of the effectiveness of community development on naturally mychorrhizal mushroom cultivation technology for forest restoration and community food bank at Northern, Thailand Yotapakdee, T.1*, Inyod, T.2, Wangluk, S.2, Lattirasuvan, T.1, Mangkita, W.1, Singyoocharoen, W.1 and Kosol, S.2 1Maejo University Phrae Campus, Thailand; 2Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research. Abstract: Forests in Northern Thailand have been changed to intensive farming that growing high yield crops, using fertilizers and pesticides leading to human being a harmful effect on the environment. The effectiveness community development on naturally mycorrhiza mushroom cultivation technology for forest restoration and community food bank were recorded. The community participation with knowledge transfer workshop on naturally mycorrhiza mushroom cultivation technology was in vestigated. As the result, people registered to get the knowledge around 355 but attend the workshop about 253 samples (71.27%) from 10 communities at Phrae province. Most of them were the farmers and averaged age 56.23 years old. Result found that top five of trees were Citrus reticulata Blanco., Hopea odorata Roxb., Gymnema inodorum (Lour.) Decne, Spondias pinnata (L.f.) Kurz, and Melientha suavis Pierre respectively. Naturally mycorrhizal mushroom cultivation were Astraeus hygrometricus 159 samples (62.8%) and Thaeogyroporus porentosus 152 samples (60.1%) that become food supply at community. Farmers will plant the seedling average 9 trees/person at home garden because they it will easy to get mushroom about 131 samples (51.8%) and easy to take care trees about 129 samples (51%). -

RESEARCH ARTICLE Prevalence of Opisthorchis Viverrini Infection In

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.10.5245 Opisthorchis viverrini Infection in Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Northeast Thailand RESEARCH ARTICLE Prevalence of Opisthorchis viverrini Infection in Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Northeast Thailand Soraya J Kaewpitoon1,2*, Ratana Rujirakul1, Natthawut Kaewpitoon1,2 Abstract Background: Opisthorchis viverrini infection is a serious public-health problem in Southeast Asia especially in Lao PDR and Thailand. It is associated with a number of hepatobiliary diseases and the evidence strongly indicates that liver fluke infection is the major etiology of cholangiocarcinoma.Objectives: This study aimed to determine actual levels of Opisthorchis viverrini infection in Nakhon Ratchasima province, Northeast Thailand. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted during a one year period from October 2010 to September 2011. O. viverrini infection was determined using a modified Kato’s thick smear technique and socio-demographic data were collected using predesigned semi-structured questionnaires. Results: A total of 1,168 stool samples were obtained from 516 males and 652 females, aged 5-90 years. Stool examination showed that 2.48% were infected with O. viverrini. Males were slightly more likely to be infected than females, but the different was not statistically significant. O. viverrini infection was most frequent in the 51-60 year age group and was found to be positively associated with education and occupation. Positive results were evident in 16 of 32 districts, the highest prevalence being found in Non Daeng with 16.7%, followed by Pra Thai with 11.1%, Kaeng Sanam Nang with 8.33%, and Lam Ta Men Chai (8.33%) districts. -

วารสารวิชาการสังคมศาสตร์เครือข่ายวิจัยประชาชื่น Social Science Journal of Prachachuen Research Network: SSJPRN

วารสารวิชาการสังคมศาสตร์เครือข่ายวิจัยประชาชื่น Social Science Journal of Prachachuen Research Network: SSJPRN ที่ปรึกษากิตติมศักดิ์ ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ ดร.สมหมาย ผิวสอาด อธิการบดี มหาวิทยาลัยเทคโนโลยีราชมงคลธัญบุรี ดร.อภิเทพ แซ่โค้ว ประธานเครือข่ายวิจัยประชาชื่น มหาวิทยาลัยนานาชาติแสตมฟอร์ด ที่ปรึกษา รองศาสตราจารย์ ดร.ทิพย์พาพร มหาสินไพศาล สถาบันการจัดการปัญญาภิวัฒน์ รองประธานเครือข่ายวิจัยประชาชื่น ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ ดร.วารุณี อริยวิริยะนันท์ มหาวิทยาลัยเทคโนโลยีราชมงคลธัญบุรี รองประธานเครือข่ายวิจัยประชาชื่น ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ ณรงค์ศักดิ์ จักรกรณ์ มหาวิทยาลัยราชภัฏพระนคร รองประธานเครือข่ายวิจัยประชาชื่น กองบรรณาธิการวารสาร Professor Dr. Gregory L.F. Chiu School of Engineering and Technology, Asian Institute of Technology. Professor Dr. G.V.R.K. Acharyulu School of Management Studies, University of Hyderabad, India. Professor Dr. Rahul Singh Birla Institute of Management Technology, India. ศาสตราจารย์ ดร.สุนันทา เสียงไทย School of Management, Asian Institute of Technology รองศาสตราจารย์ ดร.เชาว์ โรจนแสง สาขาวิทยาการจัดการ มหาวิทยาลัยสุโขทัยธรรมาธิราช รองศาสตราจารย์ ดร.ณัฐวุฒิ พิมพา วิทยาลัยการจัดการ มหาวิทยาลัยมหิดล รองศาสตราจารย์ ดร.สุบิน ยุระรัช ศูนย์ส่งเสริมและพัฒนางานวิจัย มหาวิทยาลัยศรีปทุม รองศาสตราจารย์ ดร.สมพล ทุ่งหว้า คณะบริหารบริหารธุรกิจ มหาวิทยาลัยรามคำแหง รองศาสตราจารย์ ดร.ปณิศา มีจินดา คณะบริหารบริหารธุรกิจ มหาวิทยาลัยเทคโนโลยีราชมงคลธัญบุรี i บรรณาธิการ ดร. กฤษดา เชียรวัฒนสุข คณะบริหารบริหารธุรกิจ มหาวิทยาลัยเทคโนโลยีราชมงคลธัญบุรี ผู้ช่วยบรรณาธิการ ดร.สุคนธ์ทิพย์ วงศ์พันธ์ คณะบริหารบริหารธุรกิจ มหาวิทยาลัยเทคโนโลยีราชมงคลธัญบุรี -

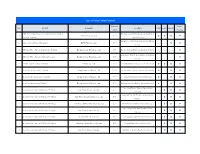

List of Solar Power Projects Capacity Public No

List of Solar Power Projects Capacity Public No. Project Company Location COP ESA IEE-SD (MW) Hearing 5 MW Photovoltaic Power Generation Project at Saraburi Tha Maprang Sub District, Kaeng Khoi District, 1 Infinite Green Co.,Ltd. 5.00 l l l l province, Thailand Saraburi Province Bang Pa-in District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya 2 Bangchak Solar Farm at Bangpa-In BCPG Public Co., Ltd. 38.00 - - l l Province 3 BSE Solar Power Plant at Chaiyaphum, Thailand Bangchak Solar Energy Co., Ltd. 8.00 Bamnet Narong District, Chaiyaphum Province - - - l Bang Pahan District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya 4 BSE Solar Power Plant at Ayutthaya,Thailand Bangchak Solar Energy Co., Ltd. 8.00 - - - l Province 5 EA Solar Farm at Lopburi, Thailand EA Solar Co., Ltd. 8.00 Phatthana Nikhom District, Lopburi Province l l l l 6 Solar Farm at Phitsanulok, Thailand Energy Absolute Public Co., Ltd. 90.00 Phrom Phiram District, Phitsanulok Province l - l l 7 Solar Farm at Nakhonsawan, Thailand Energy Absolute Public Co., Ltd. 90.00 Takhli District, Nakhon Sawan Province l - l l 8 Solar Farm at Lampang, Thailand Energy Absolute Public Co., Ltd. 90.00 Mueang Lampang District, Lampang Province l - l l Non Sung District, Nakhon Ratchasima 9 Solar Power Company 94 MW Solar PV Project Solar Power (Korat 1) Co.,Ltd. 6.00 - l l l Province Sawang Daen Din District, Sakon Nakhon 10 Solar Power Company 94 MW Solar PV Project Solar Power (Sakon Nakhon 1) Co.,Ltd. 6.00 - l l l Province 11 Solar Power Company 94 MW Solar PV Project Solar Power (Nakhon Phanom 1) Co.,Ltd. -

Draft MTR Thailand

Kingdom of Thailand Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Forest Carbon Partnership Facility(FCPF) REDD+ Readiness Project Mid-Term ReviewV2.3 Grant TF0A0984 September 2020 Acronyms and Abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank AGB Above Ground Biomass AIPP Asia Indigenous People Pact Foundation AMBIF ASEAN+3 Multi-Currency Bond Issuance Framework ASFCC ASEAN-Swiss Partnership on Social Forestry and Climate Change AWG-SF ASEAN Working Group on Social Forestry BAAC Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives BGB Below Ground Biomass BSM Benefit Sharing Mechanism BUR Business as Usual Report CCMP Climate Change Master Plan CF Carbon Fund CFM Community Forest Management COC Chain of Custody CPMU Central Project Management Unit DEDE Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency DNP Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation E&S Environmental and Social Safeguards EbA Ecosystem based-adaptation EGAT Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand EPPO Energy Policy and Planning Office ESMF Environmental Social Management Framework EU European Union EUTR EU Timber Regulation EWMI East-West Management Institute FCPF Forest Carbon Partnership Facility FGRM Feedback Grievance and Redress Mechanism FIO Forest Industry Organization FLEGT Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade FLOURISH Forest Landscape Restoration for Improved Livelihoods and Climate Resilience FLR Forest Landscape Restoration FSC Forest Stewardship Certification GFW Global -

2Nd Set of ERC and the Latter Was Graciously Appointed by HM the King on 4 July 2011, Comprising the Following Commissioners : 2Nd Set of ERC (2011 - Present)

Royal Speech by His Majesty the King Bhumibol Adulyadej “The growth of the nation is the prosperity of all people, arising out of the work or acts of all people nationwide. It can be considered that everyone has performed his duty for the benefit of the country according to his skill and capability and has lent a hand to each other. No one can live and work for the nation on his own.” An Excerpt from the Royal Guidance on the Occasion of the Bestowal of Degrees to Chulalongkorn University Graduates at Maha Chulalongkorn Building 10 July 1970 Contents Royal Speech by His Majesty the King Bhumibol Adulyadej 2 Message from the Chairman of the Energy Regulatory Commission 4 Energy Regulatory Commission 6 Office of the Energy Regulatory Commission 8 Achievements in Fiscal Year 2011 16 Various Activities in Fiscal Year 2011 28 Financial Statements and Worksheet of the OERC and the Power Development Fund in Fiscal Year 2011 31 Action Plan for Fiscal Year 2012 57 Appendices 63 Appendix 1 : Summary of the Energy Regulatory Commission Meetings 64 in Fiscal Year 2011 Appendix 2 : Summary of the Minutes of Meetings of the Sub-Committees 126 under Section 24 of the Energy Industry Act B.E. 2550 (2007) Message from the Chairman of the Energy Regulatory Commission The year 2011 has marked another important step forwards of the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) and the Office of the Energy Regulatory Commission (OERC) in materializing the development of energy industry regulation of the country, in accordance with the government policy, to be more effective to strengthen the national energy security, which is a key factor enhancing the country’s competitiveness in the international arena. -

CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM (CDM-PDD) Version 03 - in Effect As Of: 28 July 2006

PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM (CDM PDD) - Version 03 CDM – Executive Board page 1 CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM (CDM-PDD) Version 03 - in effect as of: 28 July 2006 CONTENTS A. General description of project activity B. Application of a baseline and monitoring methodology C. Duration of the project activity / crediting period D. Environmental impacts E. Stakeholders’ comments Annexes Annex 1: Contact information on participants in the project activity Annex 2: Information regarding public funding Annex 3: Baseline information Annex 4: Monitoring plan PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM (CDM PDD) - Version 03 CDM – Executive Board page 2 SECTION A. General description of project activity A.1. Title of the project activity: Title: Solar Power Company 94 MW Solar PV Project Version: 01 Date: 09 January 2011 A.2. Description of the project activity: The Thailand national electricity grid provides electricity to households across Thailand. Over 90% of electricity consumed in Thailand’s grid is supplied by fossil fuel fired power plants which emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Solar Power Company Limited intends to construct solar photovoltaic (PV) plants to supply clean renewable electricity to the Thailand grid. The proposed sites of the Solar Power Company PV plants are located in the Provinces of Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), Sakon Nakhon, Nakon Phanom, Loei and Khon Kaen in North Eastern Thailand. The project is expected to yield an electricity production of approximately 142,944 MWhe (in the first year of crediting) from 97.98 MW DC of PV capacity at sixteen sites. Electricity produced by the project activity would otherwise have involved the release of CO2 from the combustion of fossil fuels in the power plants connected to the Thailand national grid. -

2010 PR Awardees.Pdf

UNESCO Bangkok UNESCO Office, Jakarta Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education Science Cluster office to Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Cluster Office to Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Timor-Leste BRIEF INFORMATION 15 OCTOBER 2010 Nineteen products received the UNESCO Award of Excellence for Handicrafts in Southeast Asia 2010 Jakarta, 15 October 2010 – The UNESCO Award of Excellence for Handicrafts has been granted to 19 artisans from a total 112 entries in the South-East Asian Region. At the occasion of the 25th Trade Expo Indonesia, held in Jakarta from 13 to 17 October, awarding ceremony of UNESCO Award of Excellence for Handicrafts 2010 will be organized at the International Jakarta Expo, Hall D2, on 16 October 2010 from 17:00- 20:00. During this ceremony, 19 awarded artisans of the UNESCO Award of Excellence for Handicrafts 2010 will be announced. In the presence of the Minister of Trade of The Republic of Indonesia, H.E. Dr Mari Elka Pangestu, Representatives of the Indonesian National Chapter of ASEAN Handicraft Promotion and Development Association (AHPADA, Indonesia or INAC), Deputy Chief of Mission of Thailand, Mr Vutti Vuttisant and Head of Culture Unit of the UNESCO Office, Jakarta, Mr. Masanori Nagaoka, the official certificates will be handed over to the awarded artisans during the ceremony. Jointly organized by the INAC and UNESCO Bangkok and Jakarta Offices, this year's programme was supported by the Indonesian Ministry of Trade, the Ministry of Industry, the Ministry of Cooperatives, Small and Medium Enterprises, the SMESCO-UKM Gallery, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the Ministry of National Education, and the Indonesian National Commission for UNESCO. -

The Ancestral Spirit Forest (Don Pu Ta) 2 and the Role Behavior of Elders (Thao Cham) in Northeastern Thailand

Boonyong Kettate 1 The Ancestral Spirit Forest (Don Pu Ta) 2 and the Role Behavior of Elders (Thao Cham) in Northeastern Thailand Introduction or the centuries that human beings have lived The structure built as the residence for the Fclosely with nature, despite changing Pu Ta spirits is known variously as the Ho Pu conditions and the increasing role played in daily. Ta, San Pu Ta, Tup Pu Ta, or Hong Pu Ta. 4 life by technological advances, forest resources There are two types of structures. The first is a and produce have had continued value. This has small house placed atop a single pillar similar been true regardless of whether the produce is in form to a San Phra Phum (spirit house). The wild greens, herbs, dyestuffs, items of apparel, or second is built using four pillars. There are both objects that could be used as agricultural tools. large and small structures. Generally there is a The value of these products from the forest has single room in the house to make it easy to served to evoke within the peoples of different place offerings or figurines of human beings communities the desire to preserve the balance of which it is believed the spirits desire. One such nature and protect watershed sources, soil quality, figurine, made of sculpted wood in the shape of and the rich diversity of wildlife. a servant or retainer providing utensils to the According to northeastern Thai tradition, spirit, is placed at the front of the room. On when a village was established, the villagers another side may be a kind ofbalcony on which built a small bamboo shrine or hut of some sort offerings can be placed. -

Download Document

GOLD STANDARD PASSPORT CONTENTS A. Project title B. Project description C. Proof of project eligibility D. Unique Project Identification E. Outcome stakeholder consultation process F. Outcome sustainability assessment G. Sustainability monitoring plan H. Additionality and conservativeness deviations Annex 1 ODA declarations Annex 2 SFR consultation documents SECTION A. Project Title [See Toolkit 1.6] Title: Solar Power Company 94 MW Solar PV Project Date: 23 March 2014 Version no.: 3 SECTION B. Project description [See Toolkit 1.6] Solar Power Company Limited has constructed solar photovoltaic (PV) plants to supply clean renewable electricity to the Thailand grid. The proposed sites of the Solar Power Company PV plants are located in the Provinces of Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), Sakon Nakhon, Nakhon Phanom and Khon Kaen in North Eastern Thailand. The project will be capable of yielding an electricity production of approximately 109,213 MWhe (when newly installed) from 81.53 MW DC of PV capacity at twelve sites. Electricity produced by the project activity would otherwise have involved the release of CO2 from the combustion of fossil fuels in the power plants connected to the Thailand national grid. The estimated project start sate is 22 October 2009. SECTION C. Proof of project eligibility C.1. Scale of the Project Project Type Large Small C.2. Host Country Kingdom of Thailand C.3. Project Type Project type Yes No Does your project activity classify as a Renewable Energy project? Does your project activity classify as an End-use Energy Efficiency Improvement project? Does your project activity classify as waste handling and disposal project? Please justify the eligibility of your project activity: The project is a CDM registered Solar Farm undergoing retroactive Gold Standard certification. -

7 Years of Engagement to Toxic Jellyfish Surveillance System And

Committee of article evaluation Prof.Dr. Narin Hiransuthikul, M.D. Chulalongkorn University Assoc.Prof.Dr. Sarunya Hengpraprom Chulalongkorn University Assoc.Prof.Dr. Avorn Opatpatanakit Chiang Mai University Dr. Guntima Sirijeerachai Suranaree University of Technology Asst.Prof.Dr. Sang-arun Isaramalai Prince of Songkla University Dr.Wattana Rattanaprom Suratthani Rajabhat University Assoc.Prof. Mookda Suksawat Rajamangala University of Technology Srivijay 2 Asst.Prof.Dr. Nate Hongkrailert Mahidol University ISBN (E-book): 978-616-395-806-8 Assoc.Prof.Dr. Chanwit Tiamboonprasert Socially-engaged Scholarship Srinakharinwirot University Published by: Engagement Thailand (EnT) Asst.Prof.Dr. Jakrit Yaeram www.engagementthailand.org Rajamangala University of Technology Isan Support by: The Thailand Research Fund (TRF) Dr. Thanawat Jomprasert th Uttaradit Rajabhat University 14 Floor, SM Tower, Socially-engaged Scholarship 979/17-21 Phaholyothin Road, Asst.Prof.Pacharin Dumronggittigule The Thailand Research Fund Samsan Nai, Phyathai, Bangkok Dr. Kitti Satjawattana 10400 University of Phayao www.trf.or.th Working group Prof.Dr. Piyawat Boon-Long Dr. Nongyao Sripromsuk Ms. Shompunut Suankratay Ms. Patchaya Masomboon Ms. Naraporn Teerakulyanapan Message from The Chairman Engagement Thailand Engagement Thailand (EnT) came into existence as a result of an alliance formed by a number of universities in Thailand. These universities share one admirable mission to advocate the creation of the management and administration system for more rigorous university-society engagement and the integration of all aspects of their missions for the benefit of the society. Such system will call for a development of manpower who are passionate about engagement ideology and equipped with knowledge of and skills for undertaking university-society engagement activities in a systematic and sustainable manner.