Detection and Behavior of Pan Wakes in Saturn's a Ring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:1912.09192V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 24 Feb 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2925/arxiv-1912-09192v2-astro-ph-ep-24-feb-2020-2925.webp)

Arxiv:1912.09192V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 24 Feb 2020

Draft version February 25, 2020 Typeset using LATEX preprint style in AASTeX62 Photometric analyses of Saturn's small moons: Aegaeon, Methone and Pallene are dark; Helene and Calypso are bright. M. M. Hedman,1 P. Helfenstein,2 R. O. Chancia,1, 3 P. Thomas,2 E. Roussos,4 C. Paranicas,5 and A. J. Verbiscer6 1Department of Physics, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844 2Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, Cornell University, Ithaca NY 14853 3Center for Imaging Science, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester NY 14623 4Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, G¨ottingen,Germany 37077 5APL, John Hopkins University, Laurel MD 20723 6Department of Astronomy, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904 ABSTRACT We examine the surface brightnesses of Saturn's smaller satellites using a photometric model that explicitly accounts for their elongated shapes and thus facilitates compar- isons among different moons. Analyses of Cassini imaging data with this model reveals that the moons Aegaeon, Methone and Pallene are darker than one would expect given trends previously observed among the nearby mid-sized satellites. On the other hand, the trojan moons Calypso and Helene have substantially brighter surfaces than their co-orbital companions Tethys and Dione. These observations are inconsistent with the moons' surface brightnesses being entirely controlled by the local flux of E-ring par- ticles, and therefore strongly imply that other phenomena are affecting their surface properties. The darkness of Aegaeon, Methone and Pallene is correlated with the fluxes of high-energy protons, implying that high-energy radiation is responsible for darkening these small moons. Meanwhile, Prometheus and Pandora appear to be brightened by their interactions with nearby dusty F ring, implying that enhanced dust fluxes are most likely responsible for Calypso's and Helene's excess brightness. -

Cassini Update

Cassini Update Dr. Linda Spilker Cassini Project Scientist Outer Planets Assessment Group 22 February 2017 Sols%ce Mission Inclina%on Profile equator Saturn wrt Inclination 22 February 2017 LJS-3 Year 3 Key Flybys Since Aug. 2016 OPAG T124 – Titan flyby (1584 km) • November 13, 2016 • LAST Radio Science flyby • One of only two (cf. T106) ideal bistatic observations capturing Titan’s Northern Seas • First and only bistatic observation of Punga Mare • Western Kraken Mare not explored by RSS before T125 – Titan flyby (3158 km) • November 29, 2016 • LAST Optical Remote Sensing targeted flyby • VIMS high-resolution map of the North Pole looking for variations at and around the seas and lakes. • CIRS last opportunity for vertical profile determination of gases (e.g. water, aerosols) • UVIS limb viewing opportunity at the highest spatial resolution available outside of occultations 22 February 2017 4 Interior of Hexagon Turning “Less Blue” • Bluish to golden haze results from increased production of photochemical hazes as north pole approaches summer solstice. • Hexagon acts as a barrier that prevents haze particles outside hexagon from migrating inward. • 5 Refracting Atmosphere Saturn's• 22unlit February rings appear 2017 to bend as they pass behind the planet’s darkened limb due• 6 to refraction by Saturn's upper atmosphere. (Resolution 5 km/pixel) Dione Harbors A Subsurface Ocean Researchers at the Royal Observatory of Belgium reanalyzed Cassini RSS gravity data• 7 of Dione and predict a crust 100 km thick with a global ocean 10’s of km deep. Titan’s Summer Clouds Pose a Mystery Why would clouds on Titan be visible in VIMS images, but not in ISS images? ISS ISS VIMS High, thin cirrus clouds that are optically thicker than Titan’s atmospheric haze at longer VIMS wavelengths,• 22 February but optically 2017 thinner than the haze at shorter ISS wavelengths, could be• 8 detected by VIMS while simultaneously lost in the haze to ISS. -

Titan and the Moons of Saturn Telesto Titan

The Icy Moons and the Extended Habitable Zone Europa Interior Models Other Types of Habitable Zones Water requires heat and pressure to remain stable as a liquid Extended Habitable Zones • You do not need sunlight. • You do need liquid water • You do need an energy source. Saturn and its Satellites • Saturn is nearly twice as far from the Sun as Jupiter • Saturn gets ~30% of Jupiter’s sunlight: It is commensurately colder Prometheus • Saturn has 82 known satellites (plus the rings) • 7 major • 27 regular • 4 Trojan • 55 irregular • Others in rings Titan • Titan is nearly as large as Ganymede Titan and the Moons of Saturn Telesto Titan Prometheus Dione Titan Janus Pandora Enceladus Mimas Rhea Pan • . • . Titan The second-largest moon in the Solar System The only moon with a substantial atmosphere 90% N2 + CH4, Ar, C2H6, C3H8, C2H2, HCN, CO2 Equilibrium Temperatures 2 1/4 Recall that TEQ ~ (L*/d ) Planet Distance (au) TEQ (K) Mercury 0.38 400 Venus 0.72 291 Earth 1.00 247 Mars 1.52 200 Jupiter 5.20 108 Saturn 9.53 80 Uranus 19.2 56 Neptune 30.1 45 The Atmosphere of Titan Pressure: 1.5 bars Temperature: 95 K Condensation sequence: • Jovian Moons: H2O ice • Saturnian Moons: NH3, CH4 2NH3 + sunlight è N2 + 3H2 CH4 + sunlight è CH, CH2 Implications of Methane Free CH4 requires replenishment • Liquid methane on the surface? Hazy atmosphere/clouds may suggest methane/ ethane precipitation. The freezing points of CH4 and C2H6 are 91 and 92K, respectively. (Titan has a mean temperature of 95K) (Liquid natural gas anyone?) This atmosphere may resemble the primordial terrestrial atmosphere. -

Observing the Universe

ObservingObserving thethe UniverseUniverse :: aa TravelTravel ThroughThrough SpaceSpace andand TimeTime Enrico Flamini Agenzia Spaziale Italiana Tokyo 2009 When you rise your head to the night sky, what your eyes are observing may be astonishing. However it is only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum of the Universe: the visible . But any electromagnetic signal, indipendently from its frequency, travels at the speed of light. When we observe a star or a galaxy we see the photons produced at the moment of their production, their travel could have been incredibly long: it may be lasted millions or billions of years. Looking at the sky at frequencies much higher then visible, like in the X-ray or gamma-ray energy range, we can observe the so called “violent sky” where extremely energetic fenoena occurs.like Pulsar, quasars, AGN, Supernova CosmicCosmic RaysRays:: messengersmessengers fromfrom thethe extremeextreme universeuniverse We cannot see the deep universe at E > few TeV, since photons are attenuated through →e± on the CMB + IR backgrounds. But using cosmic rays we should be able to ‘see’ up to ~ 6 x 1010 GeV before they get attenuated by other interaction. Sources Sources → Primordial origin Primordial 7 Redshift z = 0 (t = 13.7 Gyr = now ! ) Going to a frequency lower then the visible light, and cooling down the instrument nearby absolute zero, it’s possible to observe signals produced millions or billions of years ago: we may travel near the instant of the formation of our universe: 13.7 By. Redshift z = 1.4 (t = 4.7 Gyr) Credits A. Cimatti Univ. Bologna Redshift z = 5.7 (t = 1 Gyr) Credits A. -

The Temperature and Width of an Active Fissure on Enceladus

Icarus 226 (2013) 1128–1137 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus The temperature and width of an active fissure on Enceladus measured with Cassini VIMS during the 14 April 2012 South Pole flyover ⇑ Jay D. Goguen a, , Bonnie J. Buratti a, Robert H. Brown b, Roger N. Clark c, Phillip D. Nicholson d, Matthew M. Hedman d, Robert R. Howell a,e,1, Christophe Sotin a, Dale P. Cruikshank f, Kevin H. Baines a, Kenneth J. Lawrence a, John R. Spencer g, David G. Blackburn h a Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, United States b University of Arizona, Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, Tucson, AZ 85721, United States c US Geological Survey, Denver, CO 80225, United States d Astronomy Dept., Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, United States e University of Wyoming, Dept. of Geology and Geophysics, Laramie, WY 82071, United States f NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, United States g Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302, United States h The Planetary Institute for Space Research and Technologies, Lowell, AR 72745, United States article info abstract Article history: The width and temperature of the active fissures on Saturn’s satellite Enceladus provide key observable Received 30 March 2013 constraints on physical models of these geyser-like eruptions. We analyze a sequence of high spatial res- Revised 5 July 2013 olution near-infrared spectra acquired with VIMS at 0.025 s intervals during a 74 km altitude flyover of Accepted 8 July 2013 the South Pole of Enceladus by the Cassini spacecraft on 14 April 2012 UTC. -

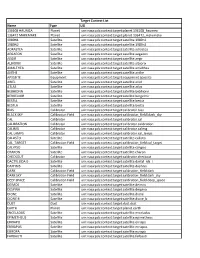

PDS4 Context List

Target Context List Name Type LID 136108 HAUMEA Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136108_haumea 136472 MAKEMAKE Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136472_makemake 1989N1 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n1 1989N2 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n2 ADRASTEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.adrastea AEGAEON Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegaeon AEGIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegir ALBIORIX Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.albiorix AMALTHEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.amalthea ANTHE Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.anthe APXSSITE Equipment urn:nasa:pds:context:target:equipment.apxssite ARIEL Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.ariel ATLAS Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.atlas BEBHIONN Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bebhionn BERGELMIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bergelmir BESTIA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestia BESTLA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestla BIAS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.bias BLACK SKY Calibration Field urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibration_field.black_sky CAL Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal CALIBRATION Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calibration CALIMG Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calimg CAL LAMPS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal_lamps CALLISTO Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.callisto -

Accretion of Saturn's Mid-Sized Moons During the Viscous

Accretion of Saturn’s mid-sized moons during the viscous spreading of young massive rings: solving the paradox of silicate-poor rings versus silicate-rich moons. Sébastien CHARNOZ *,1 Aurélien CRIDA 2 Julie C. CASTILLO-ROGEZ 3 Valery LAINEY 4 Luke DONES 5 Özgür KARATEKIN 6 Gabriel TOBIE 7 Stephane MATHIS 1 Christophe LE PONCIN-LAFITTE 8 Julien SALMON 5,1 (1) Laboratoire AIM, UMR 7158, Université Paris Diderot /CEA IRFU /CNRS, Centre de l’Orme les Merisiers, 91191, Gif sur Yvette Cedex France (2) Université de Nice Sophia-antipolis / C.N.R.S. / Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur Laboratoire Cassiopée UMR6202, BP4229, 06304 NICE cedex 4, France (3) Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, M/S 79-24, 4800 Oak Drive Pasadena, CA 91109 USA (4) IMCCE, Observatoire de Paris, UMR 8028 CNRS / UPMC, 77 Av. Denfert-Rochereau, 75014, Paris, France (5) Department of Space Studies, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado 80302, USA (6) Royal Observatory of Belgium, Avenue Circulaire 3, 1180 Uccle, Bruxelles, Belgium (7) Université de Nantes, UFR des Sciences et des Techniques, Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique, 2 rue de la Houssinière, B.P. 92208, 44322 Nantes Cedex 3, France (8) SyRTE, Observatoire de Paris, UMR 8630 du CNRS, 77 Av. Denfert-Rochereau, 75014, Paris, France (*) To whom correspondence should be addressed ([email protected]) 1 ABSTRACT The origin of Saturn’s inner mid-sized moons (Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione and Rhea) and Saturn’s rings is debated. Charnoz et al. (2010) introduced the idea that the smallest inner moons could form from the spreading of the rings’ edge while Salmon et al. -

Rings and Moons of Saturn 1 Rings and Moons of Saturn

PYTS/ASTR 206 – Rings and Moons of Saturn 1 Rings and Moons of Saturn PTYS/ASTR 206 – The Golden Age of Planetary Exploration Shane Byrne – [email protected] PYTS/ASTR 206 – Rings and Moons of Saturn 2 In this lecture… Rings Discovery What they are How to form rings The Roche limit Dynamics Voyager II – 1981 Gaps and resonances Shepherd moons Voyager I – 1980 – Titan Inner moons Tectonics and craters Cassini – ongoing Enceladus – a very special case Outer Moons Captured Phoebe Iapetus and Hyperion Spray-painted with Phoebe debris PYTS/ASTR 206 – Rings and Moons of Saturn 3 We can divide Saturn’s system into three main parts… The A-D ring zone Ring gaps and shepherd moons The E ring zone Ring supplies by Enceladus Tethys, Dione and Rhea have a lot of similarities The distant satellites Iapetus, Hyperion, Phoebe Linked together by exchange of material PYTS/ASTR 206 – Rings and Moons of Saturn 4 Discovery of Saturn’s Rings Discovered by Galileo Appearance in 1610 baffled him “…to my very great amazement Saturn was seen to me to be not a single star, but three together, which almost touch each other" It got more confusing… In 1612 the extra “stars” had disappeared “…I do not know what to say…" PYTS/ASTR 206 – Rings and Moons of Saturn 5 In 1616 the extra ‘stars’ were back Galileo’s telescope had improved He saw two “half-ellipses” He died in 1642 and never figured it out In the 1650s Huygens figured out that Saturn was surrounded by a flat disk The disk disappears when seen edge on He discovered Saturn’s -

Multi-Body Mission Design in the Saturnian System with Emphasis on Enceladus Accessibility

MULTI-BODY MISSION DESIGN IN THE SATURNIAN SYSTEM WITH EMPHASIS ON ENCELADUS ACCESSIBILITY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Todd S. Brown In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science December 2008 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ii “My Guide and I crossed over and began to mount that little known and lightless road to ascend into the shining world again. He first, I second, without thought of rest we climbed the dark until we reached the point where a round opening brought in sight the blest and beauteous shining of the Heavenly cars. And we walked out once more beneath the Stars.” -Dante Alighieri (The Inferno) Like Dante, I could not have followed the path to this point in my life without the tireless aid of a guiding hand. I owe all my thanks to the boundless support I have received from my parents. They have never sacrificed an opportunity to help me to grow into a better person, and all that I know of success, I learned from them. I’m eternally grateful that their love and nurturing, and I’m also grateful that they instilled a passion for learning in me, that I carry to this day. I also thank my sister, Alayne, who has always been the role-model that I strove to emulate. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge and extend my thanks my academic advisor, Professor Kathleen Howell, for both pointing me in the right direction and giving me the freedom to approach my research at my own pace. -

Cassini's Coolest Results for Icy Moons During the Past Two Years

Cassini’s Coolest Results for Icy Moons during the Past Two Years Dr. Bonnie J. Buratti Satellite Orbiter Science Team (SOST) Lead Visual Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) Team Senior Research Scientist Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Inst. of Technology Cassini Outreach (CHARM) Telecon August 23, 2016 Copyright 2014 California Institute of Technology. Government sponsorship acknowledged. Summary of Talk • Review of targeted flybys of the last two years • Review of small moons (“rocks”) flybys • Scientific results • End-of-Mission: what’s coming up • Monitoring jets and plumes on Enceladus • Spectacular flybys of small moons The final flybys: Dione and Enceladus Flyby Object Date Distance Flavor Goal D4 Dione 06/16/15 516 km Fields&Dust Understand the particle environment D5 Dione 08/17/15 475 km Gravity Understand the interior of Dione E20 Enceladus 10/14/15 1842 km Imaging Map the N. Pole of Enceladus E21 Enceladus 10/28/15 53 km Fields&Dust Understand the particle environment E22 Enceladus 12/19/15 5003 Imaging Understand energy balance and change Small Moons (“Rocks”) Best-ever Flybys on Dec. 6, 2015 Prometheus: 86 km wide; 37,000 km away Atlas: 30 km; 32,000 km Epimetheus: 86 km; 35,000 km E22: the last Enceladus Flyby (5003 km) Dec. 19, 2015 A view of Enceladus southern Thermal image of Damascus Sulcus, region taken during Cassini’s one of the four Tiger Stripes near final close encounter with the the south pole. enigmatic moon. Saturn can be seen in the lower background. Image of Samarkand Sulci, obtained during the E22 flyby at a distance of about 12,000 km. -

Cassini-Huygens: Recent Science Highlights and Cassini Mission Archive

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 13, EPSC-DPS2019-978-1, 2019 EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Cassini-Huygens: Recent Science Highlights and Cassini Mission Archive Linda Spilker (1) and Scott Edgington (1) (1) Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, California, USA ([email protected]) Abstract 2. Recent Science Highlights Cassini and Huygens were the most distant planetary Closest flybys to ringmoons and rings. In late 2016, orbiter and probe ever launched, arriving at Saturn in a close flyby of Titan changed Cassini’s trajectory to 2004. For the next 13 years, through its prime and two a series of 20 Ring Grazing orbits with peripases extended missions, and over almost half a Saturnian located within 10,000 km of Saturn’s F ring. These year, this spacecraft made astonishing discoveries, orbits included the closest flybys of tiny ring moons, reshaping and fundamentally changing our including Pan, Daphnis and Atlas [2] (Figure 1), and understanding of this unique planetary system [1]. remarkable views of the Daphnis-created wave on the During this time period, Cassini collected an amazing edge of the Keeler gap. These orbits also provided data set, interleaving hundreds of targets, and tens of some of the mission’s highest-resolution views of thousands of planned observations. Faced with the Saturn’s F ring, and A and B rings, and prime viewing end of the mission in September of 2017, the Cassini conditions for fine scale ring structures such as Project embarked on an ambitious effort to archive its propellers (Figure 1) and wispy clumps in the rings [3]. -

Moons and Rings

The Rings of Saturn 5.1 Saturn, the most beautiful planet in our solar system, is famous for its dazzling rings. Shown in the figure above, these rings extend far into space and engulf many of Saturn’s moons. The brightest rings, visible from Earth in a small telescope, include the D, C and B rings, Cassini’s Division, and the A ring. Just outside the A ring is the narrow F ring, shepherded by tiny moons, Pandora and Prometheus. Beyond that are two much fainter rings named G and E. Saturn's diffuse E ring is the largest planetary ring in our solar system, extending from Mimas' orbit to Titan's orbit, about 1 million kilometers (621,370 miles). The particles in Saturn's rings are composed primarily of water ice and range in size from microns to tens of meters. The rings show a tremendous amount of structure on all scales. Some of this structure is related to gravitational interactions with Saturn's many moons, but much of it remains unexplained. One moonlet, Pan, actually orbits inside the A ring in a 330-kilometer-wide (200-mile) gap called the Encke Gap. The main rings (A, B and C) are less than 100 meters (300 feet) thick in most places. The main rings are much younger than the age of the solar system, perhaps only a few hundred million years old. They may have formed from the breakup of one of Saturn's moons or from a comet or meteor that was torn apart by Saturn's gravity.