The Planning Game—English Style Or the Greater London Development Plan, 7 Urb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trends in Stroke Mortality in Greater London and South East England

Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 1997;51:121-126 121 Trends in stroke mortality in Greater London J Epidemiol Community Health: first published as 10.1136/jech.51.2.121 on 1 April 1997. Downloaded from and south east England-evidence for a cohort effect? Ravi Maheswaran, David P Strachan, Paul Elliott, Martin J Shipley Abstract to London to work in the domestic services Objective and setting - To examine time where they generally had a nutritious diet. A trends in stroke mortality in Greater Lon- study of proportional mortality from stroke don compared with the surrounding South suggested that persons born in London retained East Region of England. their lower risk of stroke when they moved Design - Age-cohort analysis based on elsewhere,3 but another study which used routine mortality data. standardised mortality ratios suggested the op- Subjects - Resident population aged 45 posite - people who moved to London acquired years or more. a lower risk of fatal stroke.4 Main outcome measure - Age specific While standardised mortality ratios for stroke stroke mortality rates, 1951-92. for all ages in Greater London are low, Health Main results - In 1951, stroke mortality of the Nation indicators for district health au- was lower in Greater London than the sur- thorities suggest that stroke mortality for rounding South East Region in all age Greater London relative to other areas may bands over 45. It has been declining in vary with age.5 both areas but the rate ofdecline has been The aim of this study was to examine time significantly slower in Greater London trends for stroke mortality in Greater London (p<0.0001). -

ALAVES - the Blessley History

Section 7 ALAVES - The Blessley History Editor’s Note - 1 When Ken Blessley agreed to complete the ALAVES story it was decided by the new Local Authority Valuers Association that it would be printed, together with the first instalment, and circulated to members. Both parts have been printed unamended, the only liberty I have taken with the text has been to combine the appendices. As reprinting necessitated retyping any subsequent errors and omissions are my responsibility. Barry Searle, 1987 Editor’s Note - 2 As part of the preparation of “A Century Surveyed”, Ken Blessley’s tour de force has been revisited. The document has been converted into computer text and is reproduced herewith, albeit in a much smaller and condensed typeface in order to reduce the number of pages. Colin Bradford, 2009 may well be inaccuracies. These can, of course, be corrected if they are of any significance. The final version will, it is hoped, be carefully conserved in the records of the Association so that possibly some ALAVES - 1949-1986 future member may be prepared to carry out a similar exercise in perhaps ten years’ time. The circulation of the story is limited, largely because of expense, but also because of the lesser interest of the majority of the current membership in what happened all those years Kenneth Blessley ago. I have therefore, confined the distribution list to the present officers and committee members, past presidents, and others who have held office for a significant period. The story of the Association of Local Authority Valuers 1. HOW IT ALL BEGAN & Estate Surveyors, 1949-1986. -

London Clerical Workers 1880-1914: the Search for Stability

London Clerical Workers 1880-1914: The Search For Stability By Michael Heller (University College London, University of London) Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in July 2003 UMI Number: U602595 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602595 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Contents Abstract............................................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgements........................................................................................... 4 Introduction................................................................................................ 5 Chapters: 1. A Definition of the Late Victorian and Edwardian London........ Clerk35 2. Work, Income, Promotion and Stability.................................................68 3. The Clerk, the Office and Work............................................................108 4. Attitudes of the Clerk towards Work.....................................................142 -

Abercrombie's Green-Wedge Vision for London: the County of London Plan 1943 and the Greater London Plan 1944

Abercrombie’s green-wedge vision for London: the County of London Plan 1943 and the Greater London Plan 1944 Abstract This paper analyses the role that the green wedges idea played in the main official reconstruction plans for London, namely the County of London Plan 1943 and the Greater London Plan 1944. Green wedges were theorised in the first decade of the twentieth century and discussed in multifaceted ways up to the end of the Second World War. Despite having been prominent in many plans for London, they have been largely overlooked in planning history. This paper argues that green wedges were instrumental in these plans to the formulation of a more modern, sociable, healthier and greener peacetime London. Keywords: Green wedges, green belt, reconstruction, London, planning Introduction Green wedges have been theorised as an essential part of planning debates since the beginning of the twentieth century. Their prominent position in texts and plans rivalled that of the green belt, despite the comparatively disproportionate attention given to the latter by planning historians (see, for example, Purdom, 1945, 151; Freestone, 2003, 67–98; Ward, 2002, 172; Sutcliffe, 1981a; Amati and Yokohari, 1997, 311–37). From the mid-nineteenth century, the provision of green spaces became a fundamental aspect of modern town planning (Dümpelmann, 2005, 75; Dal Co, 1980, 141–293). In this context, the green wedges idea emerged as a solution to the need to provide open spaces for growing urban areas, as well as to establish a direct 1 connection to the countryside for inner city dwellers. Green wedges would also funnel fresh air, greenery and sunlight into the urban core. -

The London Gazette, 9Th June 1961 4305

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 9TH JUNE 1961 4305 SECOND SCHEDULE The copies, or extracts of the Development Plan so deposited, will be open for inspection free of Lengths of Road upon which Waiting is Limited charge by aid persons- interested during usual office to Thirty Minutes in any Hour hours. Bow Street (A.378) (North side) The amendment became operative as from the 9th (a) The Waiting Bay situated between 147 yards d'ay of June 1961, but if any person aggrieved by it and 164 yards east of the River Bridge (Length desires to question the validity thereof or of any pro- 17 yards). vision contained therein on the ground that it is not (&) The Waiting Bay situated between 133 yards within the pow.ers of the Town and Country Planning and 163 yards west of Bow Bridge (Length 30 Act4 1947, or on the ground that any requirement of the Act or any regulation made thereunder has not yards). been complied with in relation to the making of the Copies of the proposed Order (together with plans amendment, he may, within six weeks from the 9th showing the roads referred to have deposited at the day of June '1961, make application to the High Court. office of -the Clerk of the Rural District Council, Dated this 8th day of June 1961. Council Offices, Langport, and at County Hall, Taunton, and may be inspected during ordinary W. O. Hart, Clerk of the London County office hours. Council. Objections to the proposals must be sent in writing The County Hall, Westminster Bridge, to the undersigned by 3rd July 1961. -

London Heathrow International Airport Terminal 5

Concepts Products Service London Heathrow International Airport Terminal 5 1 Project Report London Heathrow International Airport Terminal 5 The UK’s largest free standing building. The new Terminal 5, developed by BAA for the exclusive use of British Airways at London Heathrow International Airport, is one of the largest airport terminals in the world. The whole Terminal 5 has five floors, each the size of ten football pitches, redefining the passenger experience at Heathrow Airport and setting new standards both in terminal design and customer satisfaction. The development provides Europe’s largest and most overcrowded airport with the capacity to handle an additional 30 - 35 million passengers per annum. London Heathrow International Airport Terminal 5 Developer: BAA plc Architects: Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (formerly Richard Rogers Partnership) / Pascall & Watson Ltd Tenant: British Airways plc 2 Building new solutions. Lindner undertakes major worldwide projects in all areas of interior finishes, insulation technology, industrial services and building facades. From pre-planning through to project completion Lindner is your partner of choice. The Company’s extensive manufacturing capability enables quality to be strictly maintained whilst allowing maximum flexibility to meet individual project requirements. Environmental considerations are fundamental to all Lindner’s business principles. Through partnerships with clients Lindner turns concepts into reality. 3 Our business activities at T5 The following products were designed, manufactured and installed by Lindner - Facades - Drop & Slide Ceilings - Disc Ceilings - Raft Ceilings - Mesh Ceilings - Tubular Ceilings - Partitions - Beacons and FID Trees 4 5 Facades 6 The facade of a building is the most important part of the cladding. Terminal 5´s facades are made up of over 45,000 m² of glass, equating to 7,500 bespoke glass panels and were installed in T5A and T5B, the Car Park, the Control Tower and also at the Rail Station. -

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

Local Government in London Had Always Been More Overtly Partisan Than in Other Parts of the Country but Now Things Became Much Worse

Part 2 The evolution of London Local Government For more than two centuries the practicalities of making effective governance arrangements for London have challenged Government and Parliament because of both the scale of the metropolis and the distinctive character, history and interests of the communities that make up the capital city. From its origins in the middle ages, the City of London enjoyed effective local government arrangements based on the Lord Mayor and Corporation of London and the famous livery companies and guilds of London’s merchants. The essential problem was that these capable governance arrangements were limited to the boundaries of the City of London – the historic square mile. Outside the City, local government was based on the Justices of the Peace and local vestries, analogous to parish or church boundaries. While some of these vestries in what had become central London carried out extensive local authority functions, the framework was not capable of governing a large city facing huge transport, housing and social challenges. The City accounted for less than a sixth of the total population of London in 1801 and less than a twentieth in 1851. The Corporation of London was adamant that it neither wanted to widen its boundaries to include the growing communities created by London’s expansion nor allow itself to be subsumed into a London-wide local authority created by an Act of Parliament. This, in many respects, is the heart of London’s governance challenge. The metropolis is too big to be managed by one authority, and local communities are adamant that they want their own local government arrangements for their part of London. -

Unit 1 Hope Wharf, 37 Greenwich High Road, London SE10 8LR Long Let Nursery in Greenwich (15 Year Lease with RPI Linked Reviews)

Unit 1 Hope Wharf, 37 Greenwich High Road, London SE10 8LR Long let Nursery in Greenwich (15 year lease with RPI linked reviews) Investment Highlights Offers in excess of £625,000 • Newly constructed nursery let on a new 15 year lease • Situated within a prominent residential development in Greenwich, London • 1,491 sq ft of ground floor accommodation with outdoor space and car parking Income • Let to ‘Twinnie Day Nursery Limited’ for 15 years (without £40,000 break) at a passing rent of £40,000 per annum • 5 yearly rent reviews to the higher of RPI (collar and cap of 2% and 4%) and the open market rent. • Excellent transport links to Central London with nearby stations including Greenwich Station and Deptford Bridge DLR NIY 6.10% Location Situation London Borough of Greenwich has a population of The property is situation on Hope Wharf which is 254,557 residents (2011 census). Greenwich has located on Greenwich High Road in close proximity experienced extensive regeneration over the last 2 to both Greenwich Station and Deptford Bridge decades and attracted a large amount of DLR, both of which provide access to Central investment into the locality, including developments London and Canary Wharf. such as the New Capital Quay and the Greenwich Peninsula. Transport Links Distance Greenwich is strategically located to the south east Deptford Bridge DLR 0.2 miles of Central London with excellent transport links via Greenwich Station 0.4 miles Greenwich Station (National Rail) and Deptford A2 120 yards Bridge DLR. The area is best known for the National Maritime There’s a variety of restaurants, bars, shops and Museum, Royal Observatory, Cutty Sark and the markets nearby, including the well known Cutty O2 Arena, which attract over a million tourist each Sark and Greenwich Market which is just over a 15 year. -

South East Greater London Wales East of England West

2021 REVALUATION: REGIONAL WINNERS & LOSERS Roll over the region titles below to find out These figures have been extracted from CoStar and are based on the anticipated changes in rateable values within each individual Administrative area across England and Wales. The extent of your change in rateable value will depend on the exact location of your property. Even if you are in an area where rateable values are predicted to fall, it is important to have your assessment verified, as there may still be opportunities to secure further reductions. For a detailed analysis of the likely impact of the 2021 revaluation and advice on what to do next, please contact a member of our Business Rates team. Email us at [email protected] or visit us at lsh.co.uk INDUSTRIAL REGION AVERAGE GROWTH MIN GROWTH MIN LOCATION MAX GROWTH MAX LOCATION WALES 27% 17% Blaenau Gwent 50% Neath Port Talbot GREATER LONDON 38% 34% Hackney 44% Harrow SOUTH EAST 27% 14% Dover 44% Milton Keynes EAST OF ENGLAND 31% 18% South Norfolk 44% Brentwood EAST MIDLANDS 27% 16% Derby 36% Hinckley NORTH WEST 25% 15% Barrow-In-Furness 35% Liverpool SOUTH WEST 19% 14% West Devon 27% Swindon WEST MIDLANDS 19% 14% Tamworth 26% Solihull NORTH EAST 18% 14% South Tyneside 26% Darlington YORKSHIRE 16% 11% Doncaster 21% Hull & THE HUMBER ALL UK AVG 25% OFFICE REGION AVERAGE GROWTH MIN GROWTH MIN LOCATION MAX GROWTH MAX LOCATION EAST OF ENGLAND 23% 9% Norwich 44% Watford SOUTH WEST 18% 7% Devon 41% Bristol Core GREATER LONDON 20% 5% Covent Garden 37% Sutton SOUTH EAST 25% 17% Reading Central 33% -

The London Gazette, August 30, 1898

5216 THE LONDON GAZETTE, AUGUST 30, 1898. DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACTS, 1894 AND 1896. RETURN of OUTBREAKS of the undermentioned DISEASES for the Week ended August 27th, 1898, distinguishing Counties fincluding Boroughs*). ANTHRAX. GLANDERS (INCLUDING FARCY). County. Outbreaks Animals Animals reported. Attacked. which Animals remainec reported Oui^ Diseased during ENGLAND. No. No. County. breaks at the the reported. end of Week Northampton 2 6 the pre- as At- Notts 1 1 vious tacked. Somerset 1 1 week. Wilts 1 1 WALES. ENGLAND. No. No. No. 1 Carmarthen 1 1 London 0 15 Middlesex 1 • *• 1 Norfolk 1 SCOTLAND. Kirkcudbright 1 1 SCOTLAND. Wigtown . ... 1 1 1 1 TOTAL 8 " 12 TOTAL 10 3 17 * For convenience Berwick-upon-Tweed is considered to be in Northumberland, Dudley is con- sidered to be in Worcestershire, Stockport is considered to be in Cheshire, and the city of London ia considered to be in the county of London. ORDERS AS TO MUZZLING DOGS, Southampton. Boroughs of Portsmouth, and THE Board of Agriculture have by Order pre- Winchester (15 October, 1897). scribed, as from the dates mentioned, the Kent.—(1.) The petty sessional divisions of Muzzling of Dogs in the districts and parts of Rochester, Bearstead, Mailing, Cranbrook, Tun- districts of Local Authorities, as follows :—• bridge Wells, Tunbridge, Sevenoaks, Bromley, Berkshire.—The petty sessional divisions of and Dartford (except such portions of the petty Reading, Wokinghana, Maidenhead, and sessional divisions of Bromley and Dartford as Windsor, and the municipal borough of are subject to the provisions of the City and Maidenhead, m the county of Berks. -

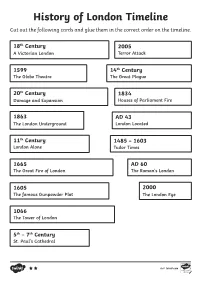

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times.