Did the New French Pay-For-Performance System Modify

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ionization Energies of Benzodiazepines Salvatore Millefiori, Andrea Alparone

Electronic properties of neuroleptics: ionization energies of benzodiazepines Salvatore Millefiori, Andrea Alparone To cite this version: Salvatore Millefiori, Andrea Alparone. Electronic properties of neuroleptics: ionization energies of benzodiazepines. Journal of Molecular Modeling, Springer Verlag (Germany), 2010, 17 (2), pp.281- 287. 10.1007/s00894-010-0723-7. hal-00590996 HAL Id: hal-00590996 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00590996 Submitted on 6 May 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Editorial Manager(tm) for Journal of Molecular Modeling Manuscript Draft Manuscript Number: JMMO1191R1 Title: Electronic properties of neuroleptics: ionization energies of benzodiazepines Article Type: Original paper Keywords: Benzodiazepines; vertical ionization energies; vertical electron affinities; DFT calculations; electron propagator theory calculations. Corresponding Author: Prof. Salvatore Millefiori, Corresponding Author's Institution: First Author: Salvatore Millefiori Order of Authors: Salvatore Millefiori; Andrea Alparone Abstract: Abstract. Vertical ionization energies (VIEs) of medazepam and nordazepam and of their molecular subunits have been calculated with the electron propagator method in the P3/CEP-31G* approximation. Vertical electron affinities (VEAs) have been obtained with a ΔSCF procedure at the DFT-B3LYP/6-31+G* level of theory. Excellent correlations have been achieved between IEcalc and IEexp allowing reliable assignment of the ionization processes. -

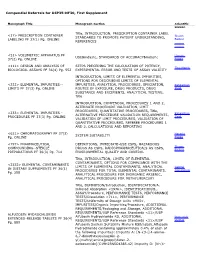

<17> PRESCRIPTION CONTAINER LABELING PF 37(1)

Compendial Deferrals for USP35-NF30, First Supplement Monograph Title Monograph Section Scientific Liaison Title, INTRODUCTION, PRESCRIPTION CONTAINER LABEL <17> PRESCRIPTION CONTAINER STANDARDS TO PROMOTE PATIENT UNDERSTANDING, Shawn LABELING PF 37(1) Pg. ONLINE Becker REFERENCES <31> VOLUMETRIC APPARATUS PF USE—, STANDARDS OF ACCURACY— Horacio 37(2) Pg. ONLINE Pappa <111> DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF STEPS PRECEDING THE CALCULATION OF POTENCY, Tina Morris BIOLOGICAL ASSAYS PF 36(4) Pg. 952 EXPERIMENTAL ERROR AND TESTS OF ASSAY VALIDITY INTRODUCTION, LIMITS OF ELEMENTAL IMPURITIES, OPTIONS FOR DESCRIBING LIMITS OF ELEMENTAL <232> ELEMENTAL IMPURITIES-- IMPURITIES, ANALYTICAL PROCEDURES, SPECIATION, Kahkashan LIMITS PF 37(3) Pg. ONLINE ROUTES OF EXPOSURE, DRUG PRODUCTS, DRUG Zaidi SUBSTANCE AND EXCIPIENTS, ANALYTICAL TESTING, Title INTRODUCTION, COMPENDIAL PROCEDURES 1 AND 2, ALTERNATE PROCEDURE VALIDATION, LIMIT PROCEDURES, QUANTITATIVE PROCEDURES, Title, <233> ELEMENTAL IMPURITIES - ALTERNATIVE PROCEDURE VALIDATION REQUIREMENTS, Kahkashan PROCEDURES PF 37(3) Pg. ONLINE Zaidi VALIDATION OF LIMIT PROCEDURES, VALIDATION OF QUANTITATIVE PROCEDURES, REFEREE PROCEDURES 1 AND 2, CALCULATIONS AND REPORTING <621> CHROMATOGRAPHY PF 37(3) SYSTEM SUITABILITY Horacio Pg. ONLINE Pappa <797> PHARMACEUTICAL DEFINITIONS, IMMEDIATE-USE CSPS, HAZARDOUS COMPOUNDING--STERILE DRUGS AS CSPS, RADIOPHARMACEUTICALS AS CSPS, Shawn Becker PREPARATIONS PF 36(3) Pg. 714 ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY AND CONTROL Title, INTRODUCTION, LIMITS OF ELEMENTAL CONTAMINANTS, -

Control Substance List

Drugs DrugID SubstanceName DEANumbScheNarco OtherNames 1 1-(1-Phenylcyclohexyl)pyrrolidine 7458 I N PCPy, PHP, rolicyclidine 2 1-(2-Phenylethyl)-4-phenyl-4-acetoxypiperidine 9663 I Y PEPAP, synthetic heroin 3 1-[1-(2-Thienyl)cyclohexyl]piperidine 7470 I N TCP, tenocyclidine 4 1-[1-(2-Thienyl)cyclohexyl]pyrrolidine 7473 I N TCPy 5 13Beta-ethyl-17beta-hydroxygon-4-en-3-one 4000 III N 6 17Alpha-methyl-3alpha,17beta-dihydroxy-5alpha-androstane 4000 III N 7 17Alpha-methyl-3beta,17beta-dihydroxy-5alpha-androstane 4000 III N 8 17Alpha-methyl-3beta,17beta-dihydroxyandrost-4-ene 4000 III N 9 17Alpha-methyl-4-hydroxynandrolone (17alpha-methyl-4-hyd 4000 III N 10 17Alpha-methyl-delta1-dihydrotestosterone (17beta-hydroxy- 4000 III N 17-Alpha-methyl-1-testosterone 11 19-Nor-4-androstenediol (3beta,17beta-dihydroxyestr-4-ene; 4000 III N 12 19-Nor-4-androstenedione (estr-4-en-3,17-dione) 4000 III N 13 19-Nor-5-androstenediol (3beta,17beta-dihydroxyestr-5-ene; 4000 III N 14 19-Nor-5-androstenedione (estr-5-en-3,17-dione) 4000 III N 15 1-Androstenediol (3beta,17beta-dihydroxy-5alpha-androst-1- 4000 III N 16 1-Androstenedione (5alpha-androst-1-en-3,17-dione) 4000 III N 17 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-4-propionoxypiperidine 9661 I Y MPPP, synthetic heroin 18 1-Phenylcyclohexylamine 7460 II N PCP precursor 19 1-Piperidinocyclohexanecarbonitrile 8603 II N PCC, PCP precursor 20 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(n)-propylthiophenethylamine 7348 I N 2C-T-7 21 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine 7399 I N DOET 22 2,5-Dimethoxyamphetamine 7396 I N DMA, 2,5-DMA 23 3,4,5-Trimethoxyamphetamine -

S1 Table. List of Medications Analyzed in Present Study Drug

S1 Table. List of medications analyzed in present study Drug class Drugs Propofol, ketamine, etomidate, Barbiturate (1) (thiopental) Benzodiazepines (28) (midazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, potassium Sedatives clorazepate, bromazepam, clobazam, alprazolam, pinazepam, (32 drugs) nordazepam, fludiazepam, ethyl loflazepate, etizolam, clotiazepam, tofisopam, flurazepam, flunitrazepam, estazolam, triazolam, lormetazepam, temazepam, brotizolam, quazepam, loprazolam, zopiclone, zolpidem) Fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil, morphine, Opioid analgesics hydromorphone, nicomorphine, oxycodone, tramadol, (10 drugs) pethidine Acetaminophen, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (36) (celecoxib, polmacoxib, etoricoxib, nimesulide, aceclofenac, acemetacin, amfenac, cinnoxicam, dexibuprofen, diclofenac, emorfazone, Non-opioid analgesics etodolac, fenoprofen, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, (44 drugs) ketoprofen, ketorolac, lornoxicam, loxoprofen, mefenamiate, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, pranoprofen, proglumetacin, sulindac, talniflumate, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid, zaltoprofen, morniflumate, pelubiprofen, indomethacin), Anticonvulsants (7) (gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, valproic acid, lacosamide) Vecuronium, rocuronium bromide, cisatracurium, atracurium, Neuromuscular hexafluronium, pipecuronium bromide, doxacurium chloride, blocking agents fazadinium bromide, mivacurium chloride, (12 drugs) pancuronium, gallamine, succinylcholine -

Optimized Determination of Lorazepam in Human Serum by Extraction and High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Analysis

Acta Pharm. 56 (2006) 481–488 Short communication Optimized determination of lorazepam in human serum by extraction and high-performance liquid chromatographic analysis AMIR G. KAZEMIFARD1* The present research was designated to evaluate a rapid 2 KHEIROLLAH GHOLAMI and sensitive method for determining low concentra- ALIREZA DABIRSIAGHI1 tions of the highly active drug lorazepam in serum. Iso- 1 Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University lation of the drug from biological fluid after addition of of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran nordazepam as the internal standard was achieved using a simple liquid-liquid extraction with dichloromethane 2 Department of Clinical Pharmacy and the extracted compounds were quantified by high- Tehran University of Medical Sciences -performance liquid chromatography. Chromatographic Tehran, Iran separation on a reversed phase column containing a sta- tionary phase with low silanol activity resulted in a per- fectly symmetrical peak with a tailing factor of 1.0. The limit of quantitation in serum is 2.5 ng mL–1 for both lo- razepam and internal standard. The procedure is rapid and sensitive enough for determination of lorazepam in serum. Keywords: lorazepam, serum, high-performance liquid Accepted September 5, 2006 chromatography, peak tailing Lorazepam [7-chloro-5-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,3-dihydro-3-hydroxy-2H-1,4-benzodiaze- pine-2-one] is a short-acting benzodiazepine that produces central depression of the CNS. It is administered in the treatment of anxiety states, insomnia associated with anxi- ety and as an anticonvulsant. Numerous clinical studies have adequately demonstrated the importance of blood concentrations of lorazepam to its efficacy and toxicity (1–4). Consequently, knowledge of the lorazepam blood levels is helpful in therapeutic drug monitoring and in the control of overdosed patients. -

Alprazolam Extended-Release Tablets

Revision Bulletin Official August 1, 2011 Alprazolam 1 Add the following: Apparatus 1: 100 rpm . Time: 1, 4, 8, and 12 h I Mobile phase: Acetonitrile, tetrahydrofuran, and Me- Alprazolam Extended-Release Tablets dium (7:1:12) Standard stock solution: 0.5 mg/mL of USP Alprazolam DEFINITION RS in acetonitrile Alprazolam Extended-Release Tablets contain NLT 90.0% Standard solution: (L/500) mg/mL of USP Alprazolam and NMT 110.0% of the labeled amount of alprazolam RS in Medium from the Standard stock solution, where L (C17H13CIN4). is the label claim in mg/Tablet IDENTIFICATION Sample solution: Pass a portion of the solution under A. The retention time of the major peak of the Sample test through a suitable filter. solution corresponds to that of the Standard solution, as Chromatographic system obtained in the Assay. (See Chromatography 〈621〉, System Suitability.) Mode: LC ASSAY Detector: UV 254 nm • PROCEDURE Column: 4.6-mm × 10-cm; 5-µm packing L7 Mobile phase: Acetonitrile, water, and phosphoric acid Flow rate: 1 mL/min (350:650:1) Injection size: 100 µL Standard solution: 0.05 mg/mL of USP Alprazolam RS System suitability in methanol Sample: Standard solution Sample solution: Transfer an appropriate number of Suitability requirements Tablets into a suitable volumetric flask to obtain a nomi- Tailing factor: NMT 2.0 nal concentration of about 0.05 mg/mL of alprazolam. Column efficiency: NLT 3000 theoretical plates Sonicate in 80% of the flask volume of methanol for 15 Relative standard deviation: NMT 2.0% min, shake mechanically for 30 min, dilute with metha- Analysis nol to final volume, filter a portion of the solution, and Samples: Standard solution and Sample solution discard the first 3 mL of filtrate. -

A Review of the Evidence of Use and Harms of Novel Benzodiazepines

ACMD Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Novel Benzodiazepines A review of the evidence of use and harms of Novel Benzodiazepines April 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Legal control of benzodiazepines .......................................................................................... 4 3. Benzodiazepine chemistry and pharmacology .................................................................. 6 4. Benzodiazepine misuse............................................................................................................ 7 Benzodiazepine use with opioids ................................................................................................... 9 Social harms of benzodiazepine use .......................................................................................... 10 Suicide ............................................................................................................................................. 11 5. Prevalence and harm summaries of Novel Benzodiazepines ...................................... 11 1. Flualprazolam ......................................................................................................................... 11 2. Norfludiazepam ....................................................................................................................... 13 3. Flunitrazolam .......................................................................................................................... -

Misbruik En Afhankelijkheid Van Benzodiazepines En Verwante Geneesmiddelen Voor De Behandeling Van Slaapproblemen Standpunt Van Een Officina-Apotheker

Farmacovigilantie: misbruik en afhankelijkheid van benzodiazepines en verwante geneesmiddelen voor de behandeling van slaapproblemen Standpunt van een officina-apotheker Dr Apr Jan Saevels Wetenschappelijk Directeur, APB 15.10.2019 1 Agenda 1) Enkele evoluties in ambulant verbruik 2) Patient met een klacht van slapeloosheid in de apotheek 3) Patient met een voorschrift Primoprescriptie Herhaalvoorschrift 4) Afbouwschema’s 5) Slotbemerkingen Enkele evoluties in ambulant verbruik « Benzodiazepines en verwanten » N03AE01 clonazepam N05BA01 diazepam N05BA02 chlordiazepoxide # packs dispensed N05BA04 oxazepam N05BA05 clorazepate potassium 15 000 000 N05BA06 lorazepam N05BA08 bromazepam 14 500 000 N05BA09 clobazam 14 000 000 N05BA10 ketazolam N05BA11 prazepam 13 500 000 N05BA12 alprazolam N05BA16 nordazepam 13 000 000 N05BA18 ethyl loflazepate N05BA21 clotiazepam 12 500 000 N05BA22 cloxazolam N05CD01 flurazepam 12 000 000 N05CD02 nitrazepam 11 500 000 N05CD03 flunitrazepam N05CD05 triazolam 11 000 000 N05CD06 lormetazepam N05CD07 temazepam 10 500 000 N05CD08 midazolam N05CD09 brotizolam 10 000 000 N05CD11 loprazolam N05CF01 zopiclone N05CF02 zolpidem 2016 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2017 2018 N05CF03 zaleplon 2002 Bron IQVIA Verwerking APB Statistics « Benzodiazepines en verwanten » N03AE01 clonazepam N05BA01 diazepam # DDD dispensed N05BA02 chlordiazepoxide N05BA04 oxazepam 500 000 000 N05BA05 clorazepate potassium N05BA06 lorazepam 490 000 000 N05BA08 bromazepam N05BA09 clobazam 480 000 000 N05BA10 ketazolam -

WO 2008/137960 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date PCT 13 November 2008 (13.11.2008) WO 2008/137960 Al (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agents: GRUMBLING, Matthew, V. et al; Wilson Son- A61K 37/55 (2006.01) sini Goodrich & Rosati, 650 Page Mill Road, Palo Alto, CA 94304-1050 (US). (21) International Application Number: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every PCT/US2008/062961 kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT,AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, (22) International Filing Date: 7 May 2008 (07.05.2008) CH, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, (25) Filing Language: English IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, (26) Publication Language: English MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, SV, (30) Priority Data: SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, 60/916,550 7 May 2007 (07.05.2007) US ZA, ZM, ZW (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, QUESTOR PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. [US/US]; GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, 3260 Whipple Road, Union City, CA 94587 (US). -

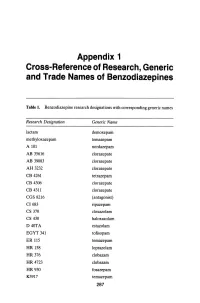

Appendix 1 Cross-Reference of Research, Generic and Trade Names of Benzodiazepines

Appendix 1 Cross-Reference of Research, Generic and Trade Names of Benzodiazepines Table 1. Benzodiazepine research designations with corresponding generic names Research Designation Generic Name lactam demoxepam methyloxazepam temazepam A 101 nordazepam AB 35616 clorazepate AB 39083 clorazepate AH 3232 clorazepate CB 4261 tetrazepam CB 4306 clorazepate CB 4311 clorazepate CGS 8216 (antagonist) CI683 ripazepam CS 370 cloxazolam CS 430 haloxazolam D40TA estazolam EGYT 341 tofisopam ER 115 temazepam HR 158 loprazolam HR376 clobazam HR 4723 clobazam HR930 fosazepam K3917 temazepam 287 THE BENZODIAZEPINES Research Designation Generic Name LA 111 diazepam LM 2717 clobazam ORF 8063 triflubazam Ro 4-5360 nitrazepam Ro 5-0690 chlordiazepoxide Ro 5-0883 desmethy1chlordiazepoxide Ro 5-2092 demoxepam Ro 5-2180 desmethyldiazepam Ro 5-2807 diazepam Ro 5-2925 desmethylmedazepam Ro 5-3059 nitrazepam Ro 5-3350 bromazepam Ro 5-3438 fludiazepam Ro 5-4023 clonazepam Ro 5-4200 flunitrazepam Ro 5-4556 medazepam Ro 5-5345 temazepam Ro 5-6789 oxazepam Ro 5-6901 flurazepam Ro 15-1788 (antagonist) Ro 21-3981 midazolam RU 31158 loprazolam S 1530 nimetazepam SAH 1123 isoquinazepam SAH 47603 temazepam SB 5833 camazepam SCH 12041 halazepam SCH 16134 quazepam U 28774 ketazolam U 31889 alprazolam U 33030 triazolam W4020 prazepam We 352 triflubazam 288 RESEARCH, GENERIC AND TRADE NAMES Research Designation Generic Name We 941 brotizolam Wy 2917 temazepam Wy 3467 diazepam Wy 3498 oxazepam Wy 3917 temazepam Wy 4036 lorazepam Wy 4082 lormetazepam Wy 4426 oxazepam Y 6047 -

INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIVE EXERCISES (ICE) Summary Report

INTERNATIONAL QUALITY ASSURANCE PROGRAMME (IQAP) INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIVE EXERCISES (ICE) Summary Report BIOLOGICAL SPECIMENS 2017/1 INTERNATIONAL QUALITY ASSURANCE PROGRAMME (IQAP) INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIVE EXERCISES (ICE) Table of contents Introduction Page 2 Comments from the International Panel of Forensic Experts Page 2 NPS reported by ICE participants Page 4 Codes and Abbreviations Page 6 Sample 1 Analysis Page 7 Identified substances Page 7 Statement of findings Page 8 Identification methods Page 11 Summary Page 14 Sample 2 Analysis Page 15 Identified substances Page 15 Statement of findings Page 18 Identification methods Page 23 Summary Page 6 2 - Z Scores Page 27 Sample 3 Analysis Page 37 Identified substances Page 37 Statement of findings Page 39 Identification methods Page 44 Summary Page 47 Z- Scores Page 48 Sample 4 Analysis Page 51 Identified substances Page 51 Statement of findings Page 54 Identification methods Page 59 Summary Page 62 Z- Scores Page 63 Test Samples Information Samples Comments on samples Sample 1 BS-1 was a blank urine test sample containing no substances from the ICE menu. Sample 2 To prepare BS-2, urine was spiked with an aqueous solution of amfetamine sulphate (1270ng base/ml) and methanol solutions of nordazepam (1960ng base/ml), oxazepam (570ng/ml) and temazepam (580ng/ml). The spiked urine was dispensed in 50ml aliquots and lyophilised. Sample 3 To prepare BS-3, urine was spiked with an aqueous solution of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) (16560ng/ml). The spiked urine was dispensed in 50ml aliquots and lyophilised. Sample 4 To prepare BS-4, urine was spiked with an aqueous solution of morphine sulphate (860ng base/ml). -

List of Benzodiazepines - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of benzodiazepines - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Talk Read Edit Our updated Terms of Use will become effective on May 25, 2012. Find out more. List of benzodiazepines From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The below tables contain a list of benzodiazepines that Benzodiazepines Contents are commonly prescribed, with their basic pharmacological Featured content characteristics such as half-life and equivalent doses to other Current events benzodiazepines also listed, along with their trade names and Random article primary uses. The elimination half-life is how long it takes for Donate to Wikipedia half of the drug to be eliminated by the body. "Time to peak" Interaction refers to when maximum levels of the drug in the blood occur Help after a given dose. Benzodiazepines generally share the About Wikipedia same pharmacological properties, such as anxiolytic, Community portal sedative, hypnotic, skeletal muscle relaxant, amnesic and Recent changes anticonvulsant (hypertension in combination with other anti The core structure of benzodiazepines. Contact Wikipedia hypertension medications). Variation in potency of certain "R" labels denote common locations of effects may exist among individual benzodiazepines. Some side chains, which give different Toolbox benzodiazepines produce active metabolites. Active benzodiazepines their unique properties. Print/export metabolites are produced when a person's body metabolizes Benzodiazepine the drug into compounds that share a similar pharmacological