Recombinant Activated Factor VII for Prevention of Bleeding Unrelated to Hemophilia: Clinical and Economic Systematic Review [Internet]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Abstract of the Thesis Of

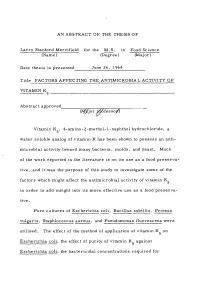

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Larry Stanford Merrifield for the M.S. in Food Science (Name) (Degree) (Major) Date thesis is presented June 26, 1964 Titie FACTORS AFFECTING THE ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF VITAMIN K 5 Abstract approved (M^jor Tp&Sfesso/) Vitamin K, 4-amino-2-methyl- 1-naphthol hydrochloride, a 5 water soluble analog of vitamin K has been shown to possess an anti- microbial activity toward many bacteria, molds, and yeast. Much of the work reported in the literature is on its use as a food preserva- tive, and it was the purpose of this study to investigate some of the factors which might affect the antimicrobial activity of vitamin K in order to add insight into its more effective use as a food preserva- tive. Pure cultures of Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Proteus vulgaris, Staphlococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas fluorescens were utilized. The effect of the method of application of vitamin K on Escherichia coli; the effect of purity of vitamin K against Escherichia coli; the bactericidal concentrations required for Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Proteus vulgaris, Staphlococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas fluorescens; the effect of an absence of oxygen; the effect of contact time with Escherichia coli; the effect of initial count/ml of Escherichia coli; and the synergistic action in combination with propylene glycol were studied. The results demonstrated that air oxidation of vitamin K was 5 necessary to obtain maximum inhibitory activity against Escherichia coli. The use of white, crystalline vitamin K synthesized in the laboratory, as compared to partially oxidized commercial prepara- tions, gave better results against Escherichia coli. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,149,560 B2 Askari Et Al

USOO9149560B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,149,560 B2 Askari et al. (45) Date of Patent: Oct. 6, 2015 (54) SOLID POLYGLYCOL-BASED 6,149,931 A 11/2000 Schwartz et al. BOCOMPATIBLE PRE-FORMULATION 6,153,211 A 11/2000 Hubbell et al. 6,180,687 B1 1/2001 Hammer et al. 6,207,772 B1 3/2001 Hatsuda et al. (71) Applicant: Medicus Biosciences LLC, San Jose, 6,312,725 B1 1 1/2001 Wallace et al. CA (US) 6,458,889 B1 10/2002 Trollsas et al. 6,475,508 B1 1 1/2002 Schwartz et al. (72) Inventors: Syed H. Askari, San Jose, CA (US); 6,547,714 B1 4/2003 Dailey 6,566,406 B1 5/2003 Pathak et al. Yeon S. Choi, Emeryville, CA (US); 6,605,294 B2 8/2003 Sawhney Paul Yu Jen Wan, Norco, CA (US) 6,624,245 B2 9, 2003 Wallace et al. 6,632.457 B1 10/2003 Sawhney (73) Assignee: Medicus Biosciences LLC, San Jose, 6,703,037 B1 3/2004 Hubbell et al. CA (US) 6,703,378 B1 3/2004 Kunzler et al. 6,818,018 B1 1 1/2004 Sawhney 7,009,343 B2 3/2006 Lim et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 7,255,874 B1 8, 2007 Bobo et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 7,332,566 B2 2/2008 Pathak et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 7,553,810 B2 6/2009 Gong et al. -

Stability of Vitamins in Pelleting

Stability of vitamins in pelleting BY N.E. WARD, PHD, MSC REVIEWED AND EDITED BY CHARLES STARK, ADAM FAHRENHOLZ, AND CASSANDRA JONES with formulation changes from the same supplier. elleting of animal feeds has been practiced for P For these reasons, historical data must be closely decades. During the pelleting process, an increased scrutinized. processing temperature is associated with the production of more tonnes of feed per hour with Vitamin stability characteristics improved pellet durability. If conditions are harsh Inherent differences exist in the stability of enough, however, reduced starch (Brown, 1996) unformulated vitamins (i.e., non-commercial forms; and protein (Batterham, et al., 1993) utilization can Baker, 1995). Thus, while heat may be especially occur. destructive to vitamin A, it has little consequence on niacin (Table 16-1). Vitamins for use in feeds In addition, the moisture, heat, friction and shear of and foods are formulated to counter anticipated pelleting can compromise the integrity of added stresses, and formulations are intended to act as a vitamins (Jones, 1986; Gadient, 1986) and enzymes buffer between the vitamin and the destructive (Nunes, 1993; Eeckhout, 1999). Taken that the component. various feed additives are inherently vulnerable to heat and moisture, this is not a minor concern. Along with the unique chemical structure and Thus, it’s important to understand the conditions characteristics of each vitamin, the anticipated that might decrease the efficacy of enzymes and stress dictates the type of stabilization or vitamins in a processed feed. formulation needed. For example, vitamin A exists with four double bonds and one hydroxyl group (Adams, 1978). -

Mega-Dose Vitamin C As Therapy for Human Cancer?

possible alternative explanation for the positive outcome.... LETTER Finally, these case reports omit the number of patients who received high-dose intravenous vitamin C therapy with no effect. Because these cases were collected over many years Mega-dose vitamin C as therapy for from several institutions, this number may be quite large and human cancer? the overall response rate quite low’’ (5). Frei and Lawson (1) also refer to the ‘‘remarkable tolerance for high-dose i.v. vitamin C’’ in a phase I trial in selected cancer patients (12) Frei and Lawson (1) paint a rosy picture of the potential of but fail to mention the conclusion of this trial: ‘‘No patient vitamin C as therapy for human cancer. The authors are lo- experienced an objective anticancer response . .’’ (12). cated at the Linus Pauling Institute and therefore are in a It is possible that ‘‘the promise of ascorbic acid in the special position to revitalize the interest in vitamin C pro- treatment of advanced cancer may lie in combination with moted by the articles of Cameron and Pauling in PNAS 30 cytotoxic agents’’ (12). As long as this has not been tested, we years ago; however, the evidence that vitamin C could help should try to avoid a new hype of vitamin C as cancer treat- human cancer patients is still thin. ment by pointing out, especially in PNAS, the limitations of 1. Chen et al. (2) find that megadose i.p. vitamin C results in an the available data. Ϸ2-fold growth decrease of a human (Ovcar 5), a mouse Piet Borst1 (PanO2), and a rat (9L) tumor xenografted into immuno- compromised mice. -

US5116406.Pdf

|||||||||||||| US005 16406A United States Patent (19) 11) Patent Number: 5,116,406 Hyeon (45) Date of Patent: May 26, 1992 (54) PLANT GROWTH REGULATING 4.799,950 l/1989 Suzuki et al. ........................... 71/89 COMPOSITION FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 75 Inventor: Suong B. Hyeon, Urawa, Japan 61-215305(A) 3/1985 Japan. (73) Assignee: Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Company, 60-72802(A) 4/1985 Japan. Inc., Tokyo, Japan 61-212502(A) 9/1986 Japan. 62-190102(A) 8/1987 Japan . (21) Appl. No.: 540,062 2059412A 8/1980 United Kingdom . 22 Filed: Jun. 19, 1990 Primary Examiner-Glennon H. Hollrah Assistant Examiner-John D. Pak (30) Foreign Application Priority Data Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Armstrong, Nikaido, Jun. 20, 1989 (JP) Japan .................................. - 155629 Marmelstein, Kubovcik & Murray 5) Int. C. ...................... A01N 41/04; AOlN 33/12 (57) ABSTRACT 52 U.S. Cl. .......................................... 71/103; 71/77; Disclosed is a plant growth regulating composition, 71/92; 71/121; 71/123 which comprises containing at least one of choline salts 58) Field of Search ..................... 71/121, 123, 77,92, and compounds having vitamin K3 activity as active 71/103 ingredients and a plant growth regulating composition, (56) References Cited and comprises containing at least one of choline salt, U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS compounds having vitamin K3 activity and compounds 4.309.205 l/1982 Kessler .................................. 7 1/21 having vitamin B activity as active ingredients. 4.337.077 1/1982 Rutherford ... ... 71/9 4,764.20 8/1988 lino et al. ................................ 7/77 3 Claims, No Drawings 5,116,406 1 2 menadiol dibutyrate. The above salts are preferably PLANT GROWTH REGULATING COMPOSITION sodium salts and potassium salts. -

3258 N:O 1179

3258 N:o 1179 LIITE 1 BILAGA 1 LÄÄKELUETTELON AINEET ÄMNENA I LÄKEMEDELSFÖRTECKNINGEN Latinankielinen nimi Suomenkielinen nimi Ruotsinkielinen nimi Englanninkielinen nimi Latinskt namn Finskt namn Svenskt namn Engelskt namn Abacavirum Abakaviiri Abakavir Abacavir Abciximabum Absiksimabi Absiximab Abciximab Acamprosatum Akamprosaatti Acamprosat Acamprosate Acarbosum Akarboosi Akarbos Acarbose Acebutololum Asebutololi Acebutolol Acebutolol Aceclofenacum Aseklofenaakki Aceklofenak Aceclofenac Acediasulfonum natricum Asediasulfoninatrium Acediasulfonnatrium Acediasulfone sodium Acepromazinum Asepromatsiini Acepromazin Acepromazine Acetarsolum Asetarsoli Acetarsol Acetarsol Acetazolamidum Asetatsoliamidi Acetazolamid Acetazolamide Acetohexamidum Asetoheksamidi Acetohexamid Acetohexamide Acetophenazinum Asetofenatsiini Acetofenazin Acetophenazine Acetphenolisatinum Asetofenoli-isatiini Acetfenolisatin Acetphenolisatin Acetylcholini chloridum Asetyylikoliinikloridi Acetylkolinklorid Acetylcholine chloride Acetylcholinum Asetyylikoliini Acetylkolin Acetylcholini Acetylcysteinum Asetyylikysteiini Acetylcystein Acetylcysteine Acetyldigitoxinum Asetyylidigitoksiini Acetyldigitoxin Acetyldigitoxin Acetyldigoxinum Asetyylidigoksiini Acetyldigoxin Acetyldigoxin Acetylisovaleryltylosini Asetyyli-isovaleryyli- Acetylisovaleryl- Acetylisovaleryltylosine tartras tylosiinitartraatti tylosintartrat tartrate Aciclovirum Asikloviiri Aciklovir Aciclovir Acidum acetylsalicylicum Asetyylisalisyylihappo Acetylsalicylsyra Acetylsalicylic acid Acidum alendronicum -

Scientific Opinion on the Safety and Efficacy of Vitamin K3 (Menadione

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals EFSA Journal 2014;12(1):3532 SCIENTIFIC OPINION Scientific Opinion on the safety and efficacy of vitamin K3 (menadione sodium bisulphite and menadione nicotinamide bisulphite) as a feed additive for all animal species1 EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP)2,3 European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Parma, Italy ABSTRACT Vitamin K describes a group of lipophilic vitamins that exist naturally in two forms: vitamin K1 (phylloquinone, found in green plants) and vitamin K2 (a group of menaquinones synthesised by bacteria in the intestine). Vitamin K3 (or menadione) is a synthetic form of vitamin K without a side chain. To become active, menadione needs to undergo prenylation. Vitamins K1, K2 and K3 are metabolically activated in the liver to become co- factors in the activation of vitamin K-dependent proteins, which are important for normal blood coagulation, and normality of bones and arteries (Gla proteins). Acute toxicity of menadione or its derivatives is reached at levels exceeding the requirements by a factor of at least 1 000. Menadione sodium bisulphite (MSB) and menadione nicotinamide bisulphite (MNB) are safe for all animal species at practical use levels in feed. The use of MSB in water for drinking is likely to increase the exposure of target animals to chromium(VI). Therefore, the FEEDAP Panel has concerns about the safety of MSB when administered by this route. The use of MSB and MNB in animal nutrition does not give rise to safety concerns for consumers. -

VITAMIN K SUBSTANCES 1. Exposure Data

VITAMIN K SUBSTANCES Vitamin K comprises a group of substances, which are widespread in nature and are an essential co-factor in humans in the synthesis of several proteins that play a role in haemostasis and others that may be important in calcium homeostasis. The K vitamins all contain the 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone (menadione) moiety, and the various naturally occurring forms differ in the alkyl substituent at the 3-position. Phylloquinone (vitamin K1) is 2-methyl-3-phytyl-1,4-naphthoquinone and is widely found in higher plants, including green leafy vegetables, and in green and blue algae. The menaquinones (formerly vitamin K2) have polyisoprenyl substituents at the 3-position and are produced by bacteria. The compound menadione (formerly vitamin K3) lacks an alkyl group at the 3-position but can be alkylated in vivo in some species. Several synthetic water-soluble derivatives, such as the sodium diphosphate ester of menadiol and the addition product of menadione with sodium bisulfite, also have commercial applications (National Research Council, 1989; Gennaro, 1995; Weber & Rüttimann, 1996). 1. Exposure Data 1.1 Chemical and physical data 1.1.1 Nomenclature, structural and molecular formulae and relative molecular masses Vitamin K (generic) Chem. Abstr. Serv. Reg. No.: 12001-79-5 Chem. Abstr. Name: Vitamin K Vitamin K1 (generic) Chem. Abstr. Serv. Reg. No.: 11104-38-4 Chem. Abstr. Name: Vitamin K1 Phylloquinone Chem. Abstr. Serv. Reg. No.: 84-80-0 Deleted CAS Reg. Nos.: 10485-69-5; 15973-57-6; 50926-17-5 –417– 418 IARC MONOGRAPHS -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,093,301 B2 Kano Et Al

USOO80933 01B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,093,301 B2 Kano et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jan. 10, 2012 (54) ANTI-ALLERGICAGENT Kimura I. et al: “Menaquinone (Vitamin K2) Therapy for Bronchial Asthma. I. Mechanism of Action of Menaquinone on Allergic Reac tions, Acta Medica Okayama, vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 73-81, 1975. (75) Inventors: Hiroshi Kano, Odawara (JP); Syuji Goreg P. et al: "Antiinflammatory and Antianaphylactic Action of Ikegami, Odawara (JP) Vitamins K1 and K3”, Arzelimittel-Forschung, vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 227-230, 1968. (73) Assignee: Meiji Co., Ltd., Tokyo (JP) Sok D.et al: "Studies on Slow Reacting Sunstances.” Chem. Nat. Prod., Proc. Sino-Am. Symp., pp. 94-103, 1980. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Lien et al: “Synthesis and Antiplatelet, Antiinflammatory, and patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Antiallergic Activities of 2-Substituted 3-Chloro-1,4- U.S.C. 154(b) by 231 days. Naphthoquinone Derivatives'. Bioorg MedChem, vol. 5, No. 12, pp. 21.11-2120, 1997. (21) Appl. No.: 12/064,917 Gallin et al: "Effects of Vitamin K on Human Neutrophil Function'. Journal of Immunology, vol. 128, No. 3, pp. 1399-408, 1982. (22) PCT Filed: Aug. 25, 2006 Lien et al: “Synthesis and Antiplatelet, Antiinflammatory and Antiallergic Activities of 2,3-Disubstituted 1,4-Naphthoguinones', (86). PCT No.: PCT/UP2OO6/316704 Chem. Pharm. Bull, vol. 44, No. 6, pp. 1181-1187, 1996. Gotthard etal: "Studies on 1.4-Naphthoguinones.”5. Mechanism of S371 (c)(1), the Antianaphylactic Activity of Plumbagin, Pharmazeutische (2), (4) Date: Feb. -

Alphabetical Listing of ATC Drugs & Codes

Alphabetical Listing of ATC drugs & codes. Introduction This file is an alphabetical listing of ATC codes as supplied to us in November 1999. It is supplied free as a service to those who care about good medicine use by mSupply support. To get an overview of the ATC system, use the “ATC categories.pdf” document also alvailable from www.msupply.org.nz Thanks to the WHO collaborating centre for Drug Statistics & Methodology, Norway, for supplying the raw data. I have intentionally supplied these files as PDFs so that they are not quite so easily manipulated and redistributed. I am told there is no copyright on the files, but it still seems polite to ask before using other people’s work, so please contact <[email protected]> for permission before asking us for text files. mSupply support also distributes mSupply software for inventory control, which has an inbuilt system for reporting on medicine usage using the ATC system You can download a full working version from www.msupply.org.nz Craig Drown, mSupply Support <[email protected]> April 2000 A (2-benzhydryloxyethyl)diethyl-methylammonium iodide A03AB16 0.3 g O 2-(4-chlorphenoxy)-ethanol D01AE06 4-dimethylaminophenol V03AB27 Abciximab B01AC13 25 mg P Absorbable gelatin sponge B02BC01 Acadesine C01EB13 Acamprosate V03AA03 2 g O Acarbose A10BF01 0.3 g O Acebutolol C07AB04 0.4 g O,P Acebutolol and thiazides C07BB04 Aceclidine S01EB08 Aceclidine, combinations S01EB58 Aceclofenac M01AB16 0.2 g O Acefylline piperazine R03DA09 Acemetacin M01AB11 Acenocoumarol B01AA07 5 mg O Acepromazine N05AA04 -

Menadione (M5625)

Menadione Product Number M 5625 Store at Room Temperature Product Description Storage/Stability Molecular Formula: C11H8O2 Alcoholic solutions of menadione are neutral by litmus Molecular Weight: 172.2 testing, and can be heated to 120 °C without CAS Number: 58-27-5 decomposition. However, menadione is destroyed by Melting point: 105-107 °C1 alkali solutions and reducing agents. It is 2 1 λmax: 245 nm, 251 nm, 333 nm recommended to protect menadione from light. Extinction coefficient: EmM = 17.8, 18.6, 2.452 Synonyms: 2-methyl-1,4-napthoquinone, Vitamin K3, References menaphthone, 2-methyl-1,4-naphthalenedione 1. The Merck Index, 12th ed., Entry# 5874. 2. Overeem, J. C., and van der Kerk, G. J. M., Menadione belongs to the Vitamin K class of Mollisin, a naturally occuring chlorine-containing compounds, which are necessary for the biosynthesis quinone. Part III. The synthesis of of prothrombin and other blood clotting factors.3 dechloromollisin methyl ether and of related Menadione is a prothrombogenic compound1 and is compounds. Rec. Trav. Chim., 83(9-10), used as a model quinone in cell culture and in vivo 1005-1022 (1964). investigations. 3. Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia, 31st ed., Reynolds, J.E.F., ed., The Pharmaceutical Press Menadione has been shown to affect gap-junctional (London, England: 1996), p. 1393. intercellular communication by mediation of tyrosine 4. Klotz, L. O., et al., 2-Methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone, phosphorylation.4 Menadione has demonstrated vitamin K(3), decreases gap-junctional intercellular cytotoxic activity against a variety of cell culture lines5 communication via activation of the epidermal and can induce apoptosis of cultured cells, such as growth factor receptor/extracellular signal- osteoclasts and osteoblasts, via elevation of peroxide regulated kinase cascade. -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2013 1/44

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2013 DDD/1000/ ATC code ATC group / INN (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 146,8152 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0760 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0760 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0760 A01AB09 Miconazole(O) 7139,2 g 0,2 g 0,0760 A01AB12 Hexetidine(O) 1541120 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+Benzocaine(C) 23900 pieces A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+Thymol(dental) 2639 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+Cetylpyridinium chloride(gingival) 179340 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+Cetrimide(O) 23565 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate(O) 824240 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+Chamomille extract(O) 317140 g A01AD86 Lidocaine+Eugenol(gingival) 1128 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 35,6598 A02A ANTACIDS 0,9596 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 0,9596 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium hydroxide(O) 591680 pieces 10 pieces 0,1261 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium hydroxide(O) 1998558 ml 50 ml 0,0852 A02AD82 Aluminium aminoacetate+Magnesium oxide(O) 463540 pieces 10 pieces 0,0988 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+Magnesium carbonate(O) 3049560 pieces 10 pieces 0,6497 A02AF Antacids with antiflatulents Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium A02AF80 1000790 ml hydroxide+Simeticone(O) DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 34,7001 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 3,5364 A02BA02 Ranitidine(O) 494352,3 g 0,3 g 3,5106 A02BA02 Ranitidine(P)