Next to Normal?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Girls Elizabeth Gilbert

AUSTRALIA JUNE 2019 City of Girls Elizabeth Gilbert The blazingly brilliant new novel from Elizabeth Gilbert, author of the international bestseller Eat Pray Love: a glittering coming-of-age epic stitched across the fabric of a lost New York Description It is the summer of 1940. Nineteen-year-old Vivian Morris arrives in New York with her suitcase and sewing machine, exiled by her despairing parents. Although her quicksilver talents with a needle and commitment to mastering the perfect hair roll have been deemed insufficient for her to pass into her sophomore year of Vassar, she soon finds gainful employment as the self-appointed seamstress at the Lily Playhouse, her unconventional Aunt Peg's charmingly disreputable Manhattan revue theatre. There, Vivian quickly becomes the toast of the showgirls, transforming the trash and tinsel only fit for the cheap seats into creations for goddesses. Exile in New York is no exile at all: here in this strange wartime city of girls, Vivian and her girlfriends mean to drink the heady highball of life itself to the last drop. And when the legendary English actress Edna Watson comes to the Lily to star in the company's most ambitious show ever, Vivian is entranced by the magic that follows in her wake. But there are hard lessons to be learned, and bitterly regrettable mistakes to be made. Vivian learns that to live the life she wants, she must live many lives, ceaselessly and ingeniously making them new. 'At some point in a woman's life, she just gets tired of being ashamed all the time. -

Threeweeks EDINBURGH

THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE EDINBURGH FESTIVAL | WEEK ONE ISSUE | WWW.THREEWEEKS.CO.UK ThreeWeeks EDINBURGH ALSO INSIDE… THE BOY WITH TAPE ON HIS FACE BRYONY KIMMINGS Edinburgh’s Eastenders: EastEnd Cabaret THE MAGNETS PLUS Luke Wright | The Grandees | Haley McGee | It’s Dark Outside | The Dead Secrets | Ben Van Der Velde 2Faced Dance Company | Cerrie Burnell | Monkey Poet | and plenty of brand new ThreeWeeks reviews START POINT Hello there,For all we’re the latest ThreeWeeks, festival newsnice to as meet it breaks you For lots of info about all things ThreeWeeks check www.ThreeWeeks.co.uk/informationwww.ThreeWeeks.co.uk/news Reaching out with a new identity: Just Festival Contents Edinburgh International Centre For talks amongst its programme, the ThreeWeeks 2013 wk1 World Spiritualities and Creative Just Festival is like a mini-Fringe in Space, we now have over 70 different itself. With such an eclectic line-up, START POINT organisations involved across the Newbigging is predictably hesitant to project”. pick out highlights. But pushed she Caro writes… 04 Billed as “an annual celebration of says: “We’re definitely excited about Letter To Edinburgh 04 culture, faith, philosophy and ideas”, the play ‘Tejas Verdes’, marking 40 religion is obviously a theme running years since the Chilean coup d’etat, A poem from Luke 04 through this particular outpost of our series of award-winning European Edinburgh’s festival month, though it films showing at The Filmhouse, and INTERVIEWS has never been just for the religious. a concert of Japanese folk music near “Our focus is on diversity” says the start”. -

Letterstoyoungerme in Support of the Roald Dahl Nurses Appeal

#LettersToYoungerMe in support of the Roald Dahl Nurses Appeal www.roalddahlcharity.org/donatewww.roalddahlcharity.org/donate My Roald Dahl Transition I firmly believe that every NHS Trust in the UK Specialist Nurse, Giselle has should have a Roald Dahl Transition Specialist helped me come to terms Nurse. Without this role, I firmly believe my son’s with becoming an adult and health would have been negatively impacted sees me as a person, not just Virginia, mum to Ben (who has Sickle Cell Disease) my condition. was supported by Roald Dahl Specialist Transition Nurse, Giselle as he moved from child to adult services Ben (25) Transition Roald Dahl’s Marvellous It’s a funny old thing, isn’t it – and on the face of There are more than 80 Roald Dahl Specialist it, it looks like it will be straight forward. Nurses based within the NHS in England, Children’s Charity Go to sleep a child, wake up a young adult. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. After all, what difference can a few hours We know that a smooth and safe transition We are appealing for donations to help establish We provide specialist nurses and make? Apart from maybe now as an adult you means young people will have better health can be more independent. outcomes, and that parents, carers and more vital Roald Dahl Transition Specialist Nurses support for seriously ill children. But we all know it’s trickier than that, especially families will be supported too. It’s one less to support more young people across the UK. Our network of 82 Roald Dahl if you have the additional complexity of being thing to worry about at a time where there are In support of our appeal, a star-studded host Specialist Nurses support over under the care of doctors and nurses. -

Representation and Portrayal on BBC Television Thematic Review Contents

Publication Date: 25 October 2018 Representation and portrayal on BBC television Thematic review Contents Summary ........................................................................................................... 3 Background to Ofcom’s thematic review ......................................................... 6 Understanding representation and portrayal is important for the BBC’s future .................................................................... 10 Key themes for the whole of the UK ............................................................... 16 Key themes in the UK’s nations and regions .................................................... 31 What’s next for the BBC? ................................................................................ 40 A1. Methodology Annex .................................................................................. 42 A2. Qualitative study recruitment details ........................................................ 46 2 Summary Ofcom has been reviewing how the BBC reflects and portrays the whole of UK society on television. This review is our most detailed piece of work in this area. It offers insight into how the BBC represents and portrays different people on TV. It will act as a baseline for assessing the BBC’s future performance and helps identify where the BBC can do more. One of the BBC’s objectives is to serve, reflect and represent people across the UK. Further, our research shows that audiences value programmes that reflect their lives. Representing the full breadth of -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Welcome to the new Scholastic Children’s Books catalogue for 2015. Here at Scholastic, we have a simple idea at the heart of everything we do. We love kids! And we hope that we know kids better than anyone. Real kids: funny, silly, sometimes tired and grumpy, hugely curious, hugely imaginative. We are very proud that Scholastic’s 2015 list has the biggest kid appeal yet. Across the country, little kids snuggling up want bedtime with Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler. The Scarecrows’ Wedding is their beautiful, pastoral picture book: an instant classic. Mermaid by TV presenter Cerrie Burnell will be another big hit, a sparkling picture book all about friendship and underwater adventure. And for bedtime fun, Alex T. Smith gives a big twist to a classic fairy tale, with wild animals and doughnuts in Little Red and the Very Hungry Lion. What about big brothers and sisters? There’s not a kid aged 7 and up who doesn’t love Tom Gates. As our favourite review says, ”Get this book, it is amazing! You would be so unlucky not to it’s extremely funny and smart.” In 2015 we have Yes No Maybe coming from Tom’s multi-talented creator, Liz Pichon. We’ve also acquired a debut by two of the funniest guys around, Sam & Mark. Jokes and pranks abound in The Adventures of Long Arm. Every kid knows that Captain Underpants is funnier than homework, so we have a brand-new Captain Underpants book for laughing your head off before spellings. For decades now, Scholastic has been publishing the most imaginative books for tweens and young adults. -

THE BBC NEWSPAPER Ord Strictly for Pudsey

photograph 17·11·09 Week 46 explore.gateway.bbc.co.uk/ariel : MIKE ALSF a THE BBC NEWSPAPER ord Strictly for Pudsey Spotlight presenter Natalie ◆Cornah and her professional partner Nick Hole took to the floor on the weekend to help raise money for Children in Need. Cornah was one of 11 presenters from Radio Cornwall, Radio Devon and Spotlight to take part in Strictly for Pudsey, a dance competition held in the Plymouth Guildhall. See Page 4 > NEWS 2-4 WEEK AT WORK 8-9 OPINION 10 MAIL 11 JOBS 14 GREEN ROOM 16 < 216 SALARIes /news aa 00·00·08 17·11·09 a 17·11·09 news 3 NEWS BITES BBC to go public with hospitality register and aggregate star salaries Pay list embraces the high As PART of Radio 1 and 1Xtra’s a anti-bullying season, Bebo, Facebook, Habbo, MSN, MySpace profile and lesser known and YouTube have teamed up to offer advice on their sites to Room 2316, White City The salary list of the top 107 Salary: £120,000 Salary: £76,300 combat online bullying. Radio 201 Wood Lane, London W12 7TS decision makers includes both Total remuneration: £127,800 Total remuneration: £81,100 1 is dealing with bullying this 020 8008 4228 household names and little week in its output and a website Editor Still more to come known managers. Their earn- MARKETIng, COMMUNICA- BBC PeoPLE has been created to support the Candida Watson 02-84222 ings encompass a wide range, TIons AND AUDIences Lucy Adams, director campaign. bbc.co.uk/bullyproo Salary: £320,000 Deputy editors by Sally Hillier they hold positions on the most senior boards as shown in these examples -

Fantastic Feasts Pot Luck Chill Seekers Cruise

FANTASTIC FEASTS 16 JANUARY,JAN 2021 MEAT AND GLUTEN-FREEREE DISHES FROM MASTERCHEFERCHEF WINNER JANE DEVONSHIRENSHIRE CHILL SEEKERS THE WINTERWATCH TEAM RETURNS TO UNCOVERER NATURE’S ICY SECRETSTS POT LUCK GIVE YOUR GARDEN YEAR-ROUND IMPACT WITH CAPTIVATING CONTAINERS CRUISE CONTROL EXPLORE THE CARIBBEAN ON A LEISURELY VOYAGE AROUND THE ISLANDS Happily ever after Davina McCall and Nicky Campbell are back with more tearjerking reunions on Long Lost Family YOUR ESSENTIAL SEVEN-DAY TV GUIDE Contents SASATURDAYTURDAY 16 JAJANUARY,NUARY 2021 4 DANCING ON ICE Meet this year’s line-up 6 MUST-SEE TV What not to miss 9 THE BAY There’s another murder to solve in Morecambe Bay 11 LONG LOST FAMILY Tissues at the ready for more emotional reunions 13 FINDING ALICE The drama with a stellar cast and addictive plot inger Beverley, whose hits Greatest Day 15 WINTERWATCH include and Bring the natural world MY WEEKEND SGet Up!, lives in London with into your home husband James O’Keefe and their dog, Zain. The 47-year-old 16 SOAPS Beverley Knight likes to spend her weekends 18 MOVIES reading and cooking up a storm 21 SPORT Twenty years ago, weekends tended to be and I’ve introduced James to the culinary 22 TV & RADIO GUIDE about going out. But these days they’re all delights of Jamaican cuisine. We’ll make brown about relaxing and spending time with James stew chicken or the traditional dish of Jamaica, 52 FOOD and our dog, Zain. On Friday, the minute I hear ackee and saltfish, which he does brilliantly. -

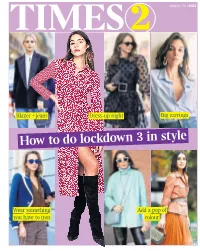

How to Do Lockdown 3 in Style

January 20 | 2021 Blazer + jeans Dress-up night Big earrings How to do lockdown 3 in style Wear something Add a pop of you have to iron colour 2 1GT Wednesday January 20 2021 | the times times2 Forget Blue Monday. It’s I knew I was February that’s the thug. An LSE study has concluded that a lot of people fib about being working class. Except this year, maybe But the assumptions others make about Carol Midgley social status are also wildly inaccurate wasn’t. “But you went to university, ow that we’re past ‘I do not miss right? I didn’t,” she said. “Just moving Blue Monday, which working in a up a few tax brackets doesn’t make you everyone knows was Those middle class. It’s an attitude, it’s the a PR brainfart garment factory’ way you do your house up, how you invented to flog ‘flawed’ handle money. I’m just like a pools holidays to shivering Sathnam Sanghera winner, a poor person who got lucky.” Ncommuters waiting murderers She doubtless had a point, but I at bus stops in the like oat milk in my coffee. I’ve think the ultimate difference between January sleet, can we turn to the The BBC has read and actively enjoyed Hilary me and people like Burchill — perhaps real culprit, the true thug of the apologised for a Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy and because immigrants and the children calendar year? I speak, obviously, of headline reading Ihave strong opinions about its of immigrants are not embarrassed February. -

Constructions, Perceptions and Expectations of Being Disabled and Young

Constructions, perceptions and expectations of being disabled and young A critical disability perspective Jenny Slater A thesis submitted for partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Psychology 2013 1 Contents List of figures and DVDs ..................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. 7 Abstract ................................................................................................................................ 8 Introduction, Theoretical Perspectives Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 9 Covering letter: Dear Mr. Reasonable ..................................................................................... 10 Defining disability (or not) ........................................................................................................... 14 Queer(y)ing .................................................................................................................................. 19 Queer(y)ing ethnography ......................................................................................................... 20 Queer(y)ing writing ................................................................................................................ -

The Media Student's Book, Fifth Edition

The Media Student’s Book The Media Student’s Book is a comprehensive introduction for students of media studies. It covers all the key topics and provides a detailed, lively and accessible guide to concepts and debates. Now in its fifth edition, this bestselling textbook has been thoroughly revised, reordered and updated, with many very recent examples and expanded coverage of the most important issues currently facing media studies. It is structured in three main parts, addressing key concepts, debates, and research skills, methods and resources. Individual chapters include: Approaching media texts • Narratives • Genres and other classifications • Representations • Globalisation • Ideologies and discourses • Media as business • ‘New media’ in a ‘new world’? • The future of television? • Regulation now • Debating advertising, branding and celebrity • News and its futures • Documentary and ‘reality’ debates • From ‘audience’ to ‘users’ • Research: skills and methods. Each chapter includes a range of examples to work with, sometimes as short case studies. They are also supported by separate, longer case studies which include: Slumdog Millionaire • Online access for film and music • CSI and crime fiction • Let the Right One In and The Orphanage • Images of migration • The Age of Stupid and climate change politics. The authors are experienced in writing, researching and teaching across different levels of undergraduate study, with an awareness of the needs of students. The book is specially designed to be easy and stimulating to use, with: • -

2019 the Power

Power 100 The Power 100 2019 #disabilitypower100 Britain’s most influential disabled people The Power 100 2019 1 Power 100 2 shaw-trust.org.uk Power 100 Welcome Welcome to the 2019 Shaw Trust Power List, a celebration of the 100 most influential disabled people in Britain. Our sincere congratulations to our top 100 influential people who have been nominated and judged by their peers to be role models, advocates, campaigners, activists and social changers. Reading each person’s story, it is clear that there is still a huge way to go to achieve equality and inclusion, but that incredible progress is being made – in the public arena and in private spaces, digitally and in real life, to many lives and to individuals – and that these changes will benefit society as a whole. Thank you to everyone who nominated someone who they felt was influential this year. Year on year the number of nominations we receive is astounding as the level of awareness and inclusion increases. But we still have much to do to create a fully inclusive and fairer society. As last year’s winner, Alex Brooker says in his interview with us (page 128): “Soaps and comedies need more disabled people in roles where it’s not all about their disability because we live normal lives too. You don’t get a lot of that in programmes. But the more you get, the more normalising it is.” This year’s nominees have come from a diverse range of sectors and have been nominated by members of the public, colleagues and those inspired by their stories. -

Ade Adepitan MBE: • Born 27Th March 1973

Crown Prosecution Service SChoolS ProjeCt Guidance for teachers how to use this pack This document provides a step-by-step approach to delivering the lessons broken down into: • An overview of the activity. • Tools required. • The learning objective. • Time required. • The learning outcome. This product has been designed as either: • 1 x 60 minute lesson or • 2 x 60 minute extended lesson to be delivered to Key Stage 3 and Key Stage 4 pupils by their PSHE teacher. The following resources have been provided as part of this pack: 1 lesson Plan (one or two lesson) 2 resource pack for pupils (one or two lesson) – To be copied for each pupil. This includes an evaluation sheet. Copy resource 2d if undertaking two hour lesson or as an optional scenario in the one hour lesson. If you wish you may choose to print one between four for resources 2a, 2b, 2c and 2d as this is a group exercise. 3 Disability hate Crime DVD which includes an electronic copy of the Guidance for teachers and the PowerPoint presentation which supports the pack. 4 resource pack – background information you may need including relevant website addresses and links to relevant National Curriculum. 2 Contents Introduction and background 5 the Crown Prosecution Service and the role of the police 6 Aims and objectives 7 one lesson: 9 Key Stage 3 & 4: lesson Plan 10 Activity one: Famous people 11 Resource 1a: Famous disabled people 13 Activity two: Disability hate crime – the legal perspective 14 Activity three: DVD – section 1 16 Activity four: Body on the wall and DVD – section