Poverty and Health in Edmonton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Neighbourhood Affordable Housing Ratios

Attachment 3 2018 Neighbourhood Affordable Housing Ratios This attachment provides an overview of the affordable housing ratios in each neighbourhood by ranges, based on City of Edmonton data. Affordable housing ratios include seniors housing, supportive housing, and co-op housing, but do not include shelters and transitional housing. The five pause neighbourhoods are highlighted in yellow. 2018 Neighbourhood Name Affordable Housing Ratio (%) 30+ Virginia Park, Woodcroft 25-30 Boyle Street, Kameyosek, Kildare, McCauley 20-25 Baranow, Richfield 16-20 Rosslyn, Strathearn 10-16 Abbottsfield, Belvedere, Beverly Heights, Canora, Carlisle, Central McDougall, Eastwood, Evansdale, Glenwood, Kensington, Kirkness, La Perle, Lee Ridge, McQueen, Pleasantview, Riverdale, Rundle Heights 5-10 Alberta Avenue, Balwin, Bannerman, Baturyn, Belmead, Belmont, Bergman, Bonnie Doon, Brander Gardens, Britannia Youngstown, Caernarvon, Calder, Canon Ridge, Casselman, Crestwood, Daly Grove, Downtown, Duggan, Dunluce, Ekota, Elmwood, Ermineskin, Hairsine, Hillview, Idylwylde, Lendrum Place, Lorelei, Menisa, Meyokumin, Michaels Park, Montrose, Northmount, Ottewell, Parkdale, Queen Alexandra, Ritchie, Sakaw, Sherwood, Sifton Park, Spruce Avenue, Steinhauer, Tipaskan, Tweddle Place, Weinlos, West Jasper Place 0-5 Albany, Aldergrove, Allard, Allendale, Ambleside, Argyll, Aspen Gardens, Athlone, Avonmore, Beacon Heights, Bearspaw, Beaumaris, Belgravia, Belle Rive, Bellevue, Bisset, Blackburne, Blue Quill, Blue Quill Estates, Breckenridge Greens, Brintnell, -

Exhibition Lands Issues and Opportunities Brief

Edmonton’s Exhibition Lands TRANSFORMATION Issues and Opportunities Brief | November 2017 1 Introduction 3 Urban Context 4 Demographics 7 Building Inventory 9 Land Ownership 9 Servicing 11 Vehicle Access and Circulation 13 Pedestrian / Cyclist Access and Circulation 15 Public Transit 17 Major Site Barriers 19 Development Potential 20 Conclusion Appendix A: Background Studies Prepared by City of Edmonton O2 Planning + Design Inc. Introduction This Issues and Opportunities Brief summarizes the technical analyses completed as part of Phase 2 of Edmonton’s Exhibition Lands Transformation (formerly named the Coliseum Station Area Redevelopment Plan). It incorporates the findings from the following project tasks: › Transportation technical analysis › Civil infrastructure technical analysis › Site visits and analysis › Context analysis › Public and stakeholder engagement The summary and discussion provided on the following pages should be supplemented by the more detailed findings of these technical studies, where available, and by the Phase 1 What We Heard Report that describes the results of public engagement to date. The Exhibition Lands project will study the lands centred on the former exhibition grounds located between the Coliseum and Stadium LRT Stations, including the Coliseum arena and EXPO Convention Centre, and the edges of surrounding communities. The study area boundaries (shown on the following pages) have been designed to encompass neighbourhoods with the highest potential for change in the future, and to enable the project to consider transitions and connections between the City lands and existing residential areas, nearby open spaces and the broader transportation network. Note that the project is in a stage of transition, with a focus on creating a more collaborative and transformational vision for the future of the Exhibition Lands. -

Edmonton - West Jasper Place Health Data and Summary

Alberta Health Primary, Community and Indigenous Health Community Profile: Edmonton - West Jasper Place Health Data and Summary 4th Edition, December 2019 Alberta Health December 2019 Community Profile: Edmonton - West Jasper Place Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. i Community Profile Summary .............................................................................................................. iii Zone Level Information ........................................................................................................................... 1 Map of Alberta Health Services Edmonton Zone...................................................................................... 2 Population Health Indicators ...................................................................................................................... 3 Table 1.1 Zone versus Alberta Population Covered as at March 31, 2018 .............................................. 3 Table 1.2 Health Status Indicators for Zone versus Alberta Residents, 2013 and 2014 (Body Mass Index, Physical Activity, Smoking, Self-Perceived Mental Health)……………………………...............3 Table 1.3 Zone versus Alberta Infant Mortality Rates (per 1,000 live births), Years 2016 – 2018…….... 4 Community Mental Health ........................................................................................................................... 5 Table 1.4 Zone versus -

Jasper Place Historic Resources Inventory Batch 4

Jasper Place Historic Resources Inventory Batch 4 Presentation<Details> to the Edmonton Historical Board March 28, 2018 © City of Edmonton © City of Edmonton SITES RECOMMENDED FOR INCLUSION ON INVENTORY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES MARCH 13, 2018, HISTORIC RESOURCES REVIEW PANEL MEETING © City of Edmonton 3 1. Richards Residence: 10245 – 153 Street NW Built c. 1932 © City of Edmonton 1. Richards Residence: 10245 – 153 Street NW Built c. 1932 © City of Edmonton 2. Imperial Building: 15110 Stony Plain Road NW Built 1956 © City of Edmonton 2. Imperial Building: 15110 Stony Plain Road NW Built 1956 © City of Edmonton 2. Imperial Building: 15110 Stony Plain Road NW Built 1956 © City of Edmonton 3. Fuller Residence: 9902 – 152 Street NW Built c. 1929 © City of Edmonton 3. Fuller Residence: 9902 – 152 Street NW Built c. 1929 © City of Edmonton 3. Fuller Residence: 9902 – 152 Street NW Built c. 1929 © City of Edmonton 4. Spurrier Residence: 9805 – 155 Street NW Built c. 1923 © City of Edmonton 4. Spurrier Residence: 9805 – 155 Street NW Built c. 1923 © City of Edmonton 5. Grant MacEwan Community College Jasper Place Campus: 10045 – 156 Street NW Built 1978-81 © City of Edmonton 5. Grant MacEwan Community College Jasper Place Campus: 10045 – 156 Street NW Built 1978-81 © City of Edmonton 5. Grant MacEwan Community College Jasper Place Campus: 10045 – 156 Street NW Built 1978-81 © City of Edmonton 5. Grant MacEwan Community College Jasper Place Campus: 10045 – 156 Street NW Built 1978-81 © City of Edmonton 5. Grant MacEwan Community College Jasper Place Campus: 10045 – 156 Street NW Built 1978-81 © City of Edmonton 5. -

JASPER PLACE SQUARE 15802 100 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta

FOR LEASE JASPER PLACE SQUARE 15802 100 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta 45% LEASED NEW RETAIL DEVELOPMENT COMING SOON Property Highlights Property Information LEGAL ADDRESS: Plan 6144AH, Block 2C, Lots 1, 2 & 3 • Introducing a 2-storey commercial development in West Edmonton Up to 7,557 sq. ft. of contiguous main SIZE: floor space or can be demised: • Daycare tenant has been secured on the second floor CRU 1: 1,739 sq ft. for 3,500 sq. ft. CRU 2: 1,047 sq. ft. • Main floor and second floor opportunity for new tenants CRU 3: 2,109 sq. ft. CRU 4: 1,402 sq. ft. • 1,062 sq. ft. outdoor patio available for a restaurant or CRU 5: 1,260 sq. ft. coffee user 2nd Floor: ±1,614 sq. ft. • Within 100m of new proposed Valley LRT plans along 156 Street PARKING: Surface parking SIGNAGE: Façade • Recent LRT proposal suggests that 100 Avenue may be a one-way traffic and Stony Plain Road will run the ZONING: CB1 opposite direction. This will further increase vehicle RENT: Negotiable exposure OPERATING COSTS: $10.00 per sq. ft. (2018 est.) • Traffic count of 17,200 vehicles per day (2015) T.I.A.: $20.00 per sq. ft. AVAILABILITY: Summer 2019 Katarina Gourlay Abdul Khurshed Suite 2700, TD Tower Associate, Retail Sales & Leasing Associate, Investment Sales 10088 102 Avenue 780 702 9082 780 917 8349 Edmonton, AB T5J 2Z1 [email protected] [email protected] www.cwedm.com Cushman & Wakefield Copyright 2018. Cushman & Wakefield Edmonton is independently owned and operated / A Member of the Cushman & Wakefield Alliance. -

Jasper Place High School Based on Edmonton Public Schools (2015 - 2016)

Jasper Place High School Based on Edmonton Public Schools (2015 - 2016) AB_SCHOOL_ POSTAL_CO SCHOOL_NAME ADDRESS WARD NUMBER DE 7104 Athlone 12940 129 Street NW T5L1J3 A 7723 Learning Store at Circle Square #2014 Northgate Centre 9499 - 137 T5E6K9 B Avenue NW 7704 Braemar 9359 67A Street NW T6B1R7 G 7127 Gold Bar 10524 46 Street NW T6A1Y3 G 7569 Winterburn 9527 Winterburn Road NW T5T5X9 C 386 Learning Store on Whyte 10007 82 Avenue NW T6E1Z2 G 7570 T. D. Baker 1750 Mill Woods Road East NW T6L5C5 I 7535 Rosslyn 13215 113A Street NW T5E5B9 A 484 amiskwaciy Academy 101 Airport Road NW T5G3K2 D Page 1 of 102 09/28/2021 Jasper Place High School Based on Edmonton Public Schools (2015 - 2016) GRADE_LEVE GRADES_OFF PHONE_NUMBER FAX_NUMBER EMAIL_ADDRESS L ERED 7804555823 7804556469 [email protected] Elementary Kindergarten to Grade 6 7804573467 7804732533 [email protected] Special Special 7804683000 7804684949 [email protected] Junior, Senior Special 7804664116 7804480429 [email protected] Elementary Kindergarten to Grade 6 7804473566 7804472403 [email protected] Elementary, Junior Kindergarten to Grade 9 7804378119 7804378190 [email protected] Special Special 7804625496 7804508560 [email protected] Junior Grade 7 to Grade 9 7804531576 7804557605 [email protected] Junior Grade 7 to Grade 9 7804241270 7804241284 [email protected] Junior, Senior Grade 7 to Grade 12 Page 2 of 102 09/28/2021 Jasper Place High School Based on Edmonton Public Schools (2015 - 2016) PROGRAMS Regular Program (K-6), Behaviour & Learning Assistance (1-6) The program serves students who are generally behind in their academics and have inconsistent attendance, as well as pregnant and parenting teens and fourth and fifth year high school students. -

Edmonton Zone Community Sites | 1

Edmonton Zone Community Sites | 1 Edmonton Zone Community Sites Carrying Community Based Naloxone Kits The community sites listed below are registered with the Community Based Naloxone Program and provide the public with lifesaving Naloxone Kits. Naloxone will temporarily reverse suspected opioid overdose or poisoning. Any overdose or poisoning response should always begin with a 911 call for emergency support. Contact the site of your choice in advance to ensure availability. Abbreviations AMH Addiction and Mental Health CHC Community Health Centre ED Emergency Department PHC Public Health Centre SCS Supervised Consumption Services/Site UC Urgent Care Community Site Name Address City Posta l Phone Hours of Operation Code Number Beaumont PHC #4918, 50 Ave. Beaumont T4X1J9 780-980-4660 Mon-Fri: 8:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Devon General Hospital - ED 101 Erie St. Devon T9G2H1 780-342-7000 24/7 Devon PHC 101 Erie St S. Devon T9G1A6 780-980-4660 Mon-Fri: 8:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Paul First Nation Health Centre Box 459, GPS coordinates: Duffield T0E1V0 780-892-2096 Mon-Fri: 8:30 a.m. - 3:30 p.m. 53°52′N 114°50′W Alberta Avenue Community League #9210, 118 Ave. Edmonton T5G0N4 587-336-5054 Thu: 5 p.m. - 8 p.m. Alberta Sex Positive Education & #12031 - 76 St NW. Edmonton T5B2C9 587-785-0889 Tue-Thu: 12 p.m. - 7 p.m., Community Centre (ASPECC) Fri-Sat: 12 p.m. - 10 p.m. AMH - East Edmonton Health Centre #7910, 112 Ave. Edmonton T5B0C2 780-342-4908 Mon-Fri: 8:15 a.m. -

West LRT Lewis Estates to Downtown Concept Plan

West LRT Lewis Estates to Downtown Concept Plan March 2011 We’re moving forward. Learn more. On January 19, 2011, City Council approved contributed to develop the plan the West LRT Concept Plan, with a modification that defines: to use Meadowlark Road north of 87 Avenue. • where the LRT tracks will fit within Consequently, the LRT will run on 87 Avenue, the route; turn left on Meadowlark Road and continue north on 156 Street, as it was presented in 2009. • where LRT stops will be located; Throughout 2010, approximately 1,200 • how access will be provided to Edmontonians provided their input and communities and businesses. Highlights www.edmonton.ca/LRTprojects • Travel time from Lewis Estates to downtown in 25 – 28 minutes; • Over 50,000 future daily boardings; • Service to West Edmonton Mall, Misericordia Hospital, Meadowlark Mall, Jasper Place Transit Centre, Jasper Gates, Oliver Square and Grant MacEwan City Centre Campus; • A new LRT line that would connect with the future Southeast LRT line and provide opportunities for transfers to the existing LRT system in the downtown core. No funding is currently in place to construct the West LRT line. LRT Network Plan In June 2009, City Council adopted a long-term LRT Network Plan that defines the future size, scale, and operation of the regional LRT system. Eventually, the LRT network will have six lines extending to the Northwest, Northeast, East, Southeast, South, and West. The LRT Network Plan supports overarching policy direction by making downtown Edmonton the focal point of the LRT system. In reviewing the overall system operation, it was determined future expansions would need to operate on a separate LRT line due to limited tunnel capacity on the existing system. -

Aboriginal Edmonton: a Statistical Story

aboriginal edmonton A Statistical Story - 2009 I II Report prepared for: Aboriginal Relations Office, City of Edmonton Prepared by: Dr. Chris Andersen Faculty of Native Studies University of Alberta Design & Layout by: Edmonton, Alberta 1SIX1 Media Ltd. III IV table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................1 About the Author: .....................................................................................................2 Aboriginal Edmonton- In a Nutshell ...................................................................3 Contextualizing The Statistical Information .....................................................4 Definitions, definitions, definitions… ................................................................6 Who, and How Many, are We? ...............................................................................9 Where Do We Live? .................................................................................................10 Differences in First Nations and Métis Residency.........................................11 Wow Long Have We Lived Here? .......................................................................12 With Whom Do We Live? ......................................................................................13 How Old Are We? ....................................................................................................15 What Kind of Education and Training Do We Undertake? .........................16 -

A Profile of Poverty in Edmonton 1 Introduction

A PROFILE OF POVERTY UPDATED IN EDMONTON MAY 2019 A report to inform the work to end poverty Acknowledgments in a generation. Thank you to Louise Ye and M.A.P.S. for the neighbourhood level maps. Thank you to Susan Morrissey Published by: of Edmonton Social Planning Council, Andrea Donini and Edmonton Social Planning Council, #200 -10544 106 ST, other members of the EndPovertyEdmonton Secretariat Edmonton, Alberta T5H-2X6 for input and feedback. Prepared by Sandra Ngo and John Kolkman This report is published by the Edmonton Social Planning Council in partnership with EndPovertyEdmonton. Design by Diva Communications Inc. Any errors, omissions, and opinions are strictly those of the authors. For a copy of this report, please visit ISBN: 978-0-921417-74-3 www.edmontonsocialplanning.ca Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. CONTENTS Introduction ________________________________________________________________________________ 2 Measuring Poverty __________________________________________________________________________ 4 Methodology _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 People Living in Low Income _____________________________________________________________________________ 8 Gender _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Visible Minority _______________________________________________________________________________________ 12 Indigenous Identity __________________________________________________________________________________ -

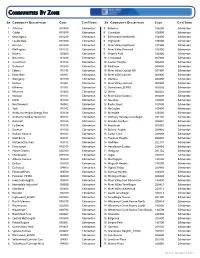

Communities by Zone

COMMUNITIES BY ZONE ZN COMMUNITY DESCRIPTION CODE CITY/TOWN ZN COMMUNITY DESCRIPTION CODE CITY/TOWN 1 Athlone 001400 Edmonton 9 Bellevue 106200 Edmonton 1 Calder 001500 Edmonton 9 Cromdale 105900 Edmonton 1 Kensington 001200 Edmonton 9 Edmonton Northlands 106600 Edmonton 1 Lauderdale 001800 Edmonton 9 Highlands 106500 Edmonton 1 Rosslyn 001300 Edmonton 9 River Valley Highlands 107400 Edmonton 1 Wellington 001100 Edmonton 9 River Valley Kinnaird 106300 Edmonton 2 Balwin 102000 Edmonton 9 Virginia Park 106800 Edmonton 2 Belvedere 101400 Edmonton 10 Crestwood 007900 Edmonton 2 Casselman 101103 Edmonton 10 Laurier Heights 008200 Edmonton 2 Delwood 101300 Edmonton 10 Parkview 008000 Edmonton 2 Ebbers 101105 Edmonton 10 River Valley Capitol Hill 007800 Edmonton 2 Evansdale 100901 Edmonton 10 River Valley Laurier 008800 Edmonton 2 Glengarry 101200 Edmonton 11 Glenora 008600 Edmonton 2 Kildare 101002 Edmonton 11 River Valley Glenora 008900 Edmonton 2 Kilkenny 101001 Edmonton 12 Downtown_EDMO 003606 Edmonton 2 Killarney 101600 Edmonton 12 Oliver 003605 Edmonton 2 Mcleod 101101 Edmonton 12 River Valley Victoria 003609 Edmonton 2 Miller 101104 Edmonton 12 Rossdale 108500 Edmonton 2 Northmount 100902 Edmonton 13 Boyle Street 109500 Edmonton 2 York 101102 Edmonton 13 McCauley 109400 Edmonton 3 Anthony Henday Energy Park 103108 Edmonton 13 Riverdale 109200 Edmonton 3 Anthony Henday Horse Hill 103107 Edmonton 14 Anthony Henday Terwillegar 202102 Edmonton 3 Brintnell 103104 Edmonton 14 Brander Gardens 200401 Edmonton 3 Cy Becker 103106 Edmonton 14 Brookside -

Bus Network Route 007 Schedule

NAIT K IN G SW information schedule guide information AY Let’s Connect Reading the Schedule ETS Real-Time N Kingsway SPRUCE ALBERTA Westmount W To find the estimated times that a bus stops Track your bus anywhere anytime from your 1 Mall 1 2 AVENUE AVENUE Centre SERVICE FREQUENT 0 /takeETS 4 at a particular location, read down the column phone or computer using these recommended 9 S S under that location. real-time tools: edmonton.ca/RealTime, Telus World T @edmontontransit T R Google Maps, third-party Transit app 7 of Science Westmount E Commonwealth To find the estimated times that a particular E ETS Connect UE NW 111 AVEN T Stadium G bus will stop at other locations, read across the R N Royal /takeETSalert O W row (left to right). A Alexandra MCCAULEY T QUEEN 1 Reading across the row tells you the time 1 Hospital ETS Text & Ride R 7 NORTH 5 MARY Accessibility D 0 WESTMOUNT 6 HIGH PARK MCQUEEN WILSON W MAYFIELD GLENORA CENTRAL required for the bus to travel between Text the bus stop number to 31100 or PARK Revised: August 29, 2021 S N N S MCDOUGALL All ETS buses and On Demand Transit T timing points. INDUSTRIAL W D T bus stop # [space] bus route # to receive R DOWNTOWN A R vehicles are accessible. 7 E O E your bus schedule by text message. E 107 AVENUE NW ENUE NW R E 107 AV BOYLE Example MACEWAN T T 7 D Bicycle Racks N L STREET N For the schedule below, to arrive at 102 St & ETS BusLink E 1 W WEST I W 4 F All ETS buses are equipped with bicycle racks 9 MacDonald Drive for 7:56 a.m., you will need Call 780-496-1600 for information about Y W EDMONTON MALL Brewery Oliver MacEwan N W A S W VE except for On Demand Transit vehicles and N A N to board the bus at Capilano Transit Centre when the next bus or LRT is scheduled to arrive.