Senior Artists in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Due to Popular Demand Mame Has Been Extended!

NEWS RELEASE FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: Elisa Hale at (860) 873-8664, ext. 323 [email protected] Dan McMahon at (860) 873-8664, ext. 324 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 2, 2012 Due to popular demand Mame has been Extended! - Unprecedented attendance spurs one week extension- - Star of Broadway’s Mamma Mia! Louise Pitre, draws fans from across the U.S. and Canada - EAST HADDAM, CONN., MAY 2, 2012: Goodspeed Musicals, the first two time Tony Award-winning theatre in the country, announced today that the tremendously popular Mame will now to play to enthusiastic audiences for 8 additional performances. This joyful and spirited musical comedy has been extended through July 7, 2012. Mame is sponsored by Liberty Bank, Mohegan Sun, and The Shops at Mohegan Sun. “Audiences are falling in love with Auntie Mame and are even coming back a second time with family and friends. We wish we could extend further, but we cannot. Our message to potential visitors? Get your tickets now!” exclaimed Executive Director Michael Price. Performances are Wednesdays at 2 and 7:30 p.m.; Thursdays at 2 and 7:30 p.m.; Fridays at 8 p.m.; Saturdays at 3 and 8 p.m.; and Sundays at 2 p.m. Added performances are: Tuesday, July 3 at 2 and 7:30 p.m.; Wednesday, July 4 at 2 p.m.; Thursday, July 5, at 2 and 7:30 p.m.; Friday, July 6, at 8 p.m.; and Saturday, July 7, at 2 and 6:30 p.m. For a complete schedule and tickets call the Box Office at 860.873.8668, open seven days a week or visit us online at www.goodspeed.org. -

Mtc Mainstage Season 2016/2017 #Mtc30 1

MUSIC THEATRE OF CONNECTICUT th 30ANNIVERSARY MTC MAINSTAGE SEASON 2016/2017 #MTC30 1 MKM Partners, LLC is an institutional equity research, sales and trading firm that provides clients with timely and unbiased fundamental, economic, proprietary/customized, technical, derivatives and event- driven research. Our team has extensive experience in the execution of U.S. and international equity orders; our fusion of high-impact analysis with first-rate execution is a combination that brings maximum value and flexibility to our clients. In addition to providing timely access to the firm’s traders and analysts, the firm focuses on providing effective communication and exceptional service to clients across both their trading and research platforms. Headquarters: Stamford, CT 300 First Stamford Place, 4th Floor, Stamford, CT 06902 Main: (203) 987-4004 Steven L. Messina President www.mkmpartners.com MEMBER OF FINRA & SIPC 2 What matters most to you in life? It’s a big question. But it’s just one of the many questions I’ll ask to better understand you, your goals and your dreams using our Confident Retirement® approach. All to help you live confidently – both today and well into the future. Bunting and Somma A private wealth advisory practice of Ameriprise Financial Services, Inc. 203.222.4994, Ext 1 1175 Post Rd East Westport, CT 06880 buntingandsomma.com The Confident Retirement® approach is not a guarantee of future financial results. Investment advisory products and services are made available through Ameriprise Financial Services, Inc., a registered -

Im a G E Fe a Tu Re S a U D Re Y D W Y E R Fro M a P H O to B Y a V Ita L Z E M E R

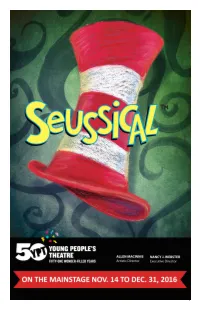

Image features Audrey Dwyer from a photo by Avital Zemer. 1 A Message from the Artistic and Executive Directors Welcome to Seussical – one of our favourite musicals at YPT. Apart from being great fun and featuring terrific performances, this is a profound story. At its centre is Horton the Elephant’s assertion that "a person’s a person no matter how small". Obviously, these are words to live by. They are also a call to action for young people – to think and care about those who are sometimes forgotten or unseen. We hope Seussical inspires all audience members, young and not so young, to be conscious of the impact of their actions. Think how much better the world would be. To quote another song from the show "Oh the thinks you can think – if you’re willing to try..." Our show runs through the Holidays with public performances every day between December 27th and 31st. Perhaps you know someone for whom Seussical tickets would make a great gift! We wish you the very best for the Holidays and the New Year to come. ALLEN MACINNIS NANCY J. WEBSTER Artistic Director Executive Director Young People’s Theatre is a member of the Professional Association of Canadian Theatres (PACT) and engages, under the terms of the Canadian Theatre Agreement, professional Artists who are members of Canadian Actors’ Equity Association. This facility is supported through Toronto Arts Council Strategic Funding. Young People’s Theatre is situated on the territories of the Mississaugas of New Credit and other Indigenous peoples, whom we acknowledge and respect. -

COMMUNITY BOND REPORT 2021 Celebrating Five Years of Collaboration, Community and Connections, Sparking Impact Within Our Walls and #Beyondthewalls

COMMUNITY BOND REPORT 2021 Celebrating five years of collaboration, community and connections, sparking impact within our walls and #beyondthewalls FINDING HOPE IN THE MIDST OF A GLOBAL PANDEMIC 2020 was a year unlike any other we have witnessed. Office buildings have been hollowed out and how we return to them will never be the same. For some, they may never return. A few of Canada’s largest companies are declaring working from home will be the new norm and they're not alone, many are following suit. Social purpose spaces (like Innovation Works) shape how our communities are designed and built, and they matter for equitable, healthy, and complete communities as well as vibrant local economies (source: Future of Good). “I am supporting the Community Bond because I believe in social purpose real estate, and believe that investing in a shared space makes our communities stronger and healthier.” -Jeffrey Good Innovation Works is a place for solutions. We default to optimism. In the face of a global pandemic, we are proud of how we responded; adapting with speed to meet the needs of our co-tenants, members and our community. We innovated, finding new ways to connect people and to spark impact. And through it all we remained hopeful, optimistic, confident of our collective ability as a community of social innovators to come out better on the other side. “As a co-creator of Innovation Works I am a believer in inclusive spaces that foster human connection and move ideas forward to spark community impact. Investing in Innovation Works in this new way is in the spirit of shared ownership and a long-term commitment.” -Michelle Baldwin HOW WE RESPONDED Our first tough call was to shut down Innovation Works, one week before the province ordered all non-essential businesses to close. -

L' Lzlv Llw S Classical

LZ_LV LLAY S L' LZLV LLW S (Continued from page 26) familiar territory with tracks like John- chised by pop radio, but not too old ny Pacheco's "Tararea Kumbayea" and for rock'n'roll. Magness did not O N S T A G E ERICK SERMON Mario Dfaz's "Corazón de Rumba" and compose any of this disc's tracks, Musk then veers into timba with "Taita Bi- but she creates an identity for her- PRODUCERS: Erick Sermon longo." There are some dips in mo- self by assembling simmering, mid - MAMMA MIA! presence whose silver hair adds a and Rockwilder mentum, including the repetitive tempo songs by such writers as Mar- Music and lyrics by Benny Andersson sexy luster to her post- hippie per- 1 Records 20023 "Déjenme Vivir." But overall, Cruz's cia Ball, Ray Charles, and James and Björn Ulvaeus sona, nailing the character's schizo- You might call it a comeback: Build- magnificent voice and overflowing Brown. She also adds a few tunes Book by Catherine Johnson phrenic turns from wistful mom and ing upon the success of his chart -top- emotion are unabated. She takes this from the popular blues lexicon, such Directed by Phyllida Lloyd scorned lover to stalwart feminist ping single, "Music," Erick Sermon straight -ahead salsa album from A to Z as the oft -covered "It's Your Voodoo Choreographed by NicholaTreherne and resuscitated disco queen. Pitre makes his triumphant return to the without resorting to ballads other Working," and sings with an expres- Sets by Jonathan Allen, Nancy Thun -or delivers some of the show's finest game with his J Records debut of the commercial ploys -for success. -

LOUISE PITRE IS MAME at GOODSPEED MUSICALS Stunning Chanteuse Will Wow Goodspeed Audiences As Mame This Spring - Mamma Mia!’S Original “Donna” Comes to Connecticut

MEDIA ALERT TONY AWARD NOMINEE LOUISE PITRE IS MAME AT GOODSPEED MUSICALS Stunning chanteuse will wow Goodspeed audiences as Mame this Spring - Mamma Mia!’s original “Donna” comes to Connecticut - Goodspeed Musicals is thrilled to announce that Tony Award nominee Louise Pitre, known as Canada’s “first lady of musical theatre,” will take on the coveted role of Mame Dennis in Mame at the Goodspeed Opera House beginning April 20th. In a career that spans theatre, television, and concert stages across North America and Europe, receiving a Tony nomination for her Broadway debut in the smash hit Mamma Mia! was a highlight for Louise Pitre. In addition to headlining the Toronto, Broadway, and US touring company casts of Mamma Mia!, Louise is known for her signature performances as Fantine in Les Misérables (Toronto, Montreal, and Paris) and the title character in Edith Piaf. She also earned raves for leading roles in Annie Get Your Gun; Song & Dance; Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well And Living In Paris; I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change; Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf?; The Roar of the Greasepaint, The Smell of the Crowd; The Toxic Avenger; and A Year With Frog and Toad. Ms. Pitre’s numerous honors include: Tony Award nomination for Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Musical for Mamma Mia! (New York), Theatre World Award, National Broadway Touring Award, Drama Desk nomination, Critics' Circle nomination, San Francisco Critics' Circle Award and more. Highlights from Louise Pitre’s concert La Vie en Rouge can be viewed at: http://www.louisepitre.com/gallery-2/video/ More information about Goodspeed Musical’s production of Mame will be announced soon. -

Anything Goes Kiss the Moon, Kiss the Sun the Donnellys

52ND ANNUAL OWEN SOUND LITTLE THEATRE PLAYBILL THE DIVALICIOUS 2012-201 3 ROXY SERIES SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS The Roxy and Country 93 Present Anything Goes Louise Pitre – From The Inside Out Mudtown Records & The Roxy Present Hats Off Country Tribute Series Music and Lyrics by Cole Porter Friday, October 12, 2012 at 8 pm Emerging Artist Series Leisa Way’s Rhinestone Cowgirl – Directed by Kathleen Cassidy Special guests: Cast of Anything Goes OTHERfolk! A Tribute to Dolly Parton Musical Director Brenda Dimoff Three of Canada’s finest performers join Thursday August 16, 2012 at 7:30 pm, Early Bird Festival All Access Pass $45 Thursday, August 30, 2012 at 7 pm, $35 November 8-10, 15-17, 21-24, 2012 at 7:30 pm forces for an exhilarating evening of musical The OTHERfolk 2012 main stage concert features Juno and Polaris Prize November 18 at 2 pm A toe-tapping tribute to Dolly, Way erupts onto theatre, original music, romance and searing nominated trio Elliott Brood, CBC Radio’s Q ‘Friday Live’ guests the stage in a flurry of feathers, fringe and When the S.S. America heads out to sea, intensity featuring award-winning Louise Pitre, Bruce Peninsula, and Pitchfork’s “Best of 2010” hometown heroes finery. The evening’s commentary is hilarious etiquette and convention fly out the portholes star of Toronto and Broadway’s Mamma Mia; Joe Matheson, Louise’s First Rate People. Visit www.otherfolk.com for more info. Follow OTHER- (“You folks paid a lot to come here tonight, as two unlikely pairs set the course for true love, proving that sometimes equally talented husband, and acclaimed pianist Diane Leah. -

Let Your Dreams Take Flight

Let your dreams take flight Featuring Olivier Award “Gloriously Goofy!”The New York Times DIRECT FROM nominated HHHH “THE SINGLE FUNNIEST THING stars Dan and Jeff! LONDON AND NEW YORK I HAVE SEEN IN AGES…YOU’RE GONNA LOVE THIS SHOW” Toronto Star HHHH “Blissfully funny, a winner in every way!” The Guardian “It’s madcap. It’s silly… It’s infectious!” Boston Globe Performed • Boston • Philadelphia • Charlotte • Pittsburgh to sold out • Chicago • San Francisco houses in • Cleveland • Toronto • Houston • Washington and more • Two successful summer engagements at the ALL SEVEN Little Shubert Theater in New York • Three record-breaking engagements in Chicago HARRY and Toronto POTTER Watch BBC’s Dan and Jeff take on the ultimate challenge, with the help of endless costumes, brilliant songs, ridiculous props, BOOKS IN and a generous helping of Hogwart’s magic. This fantastically funny show features all your favorite characters, a special SEVENTY appearance from a very frightening fire-breathing dragon, HILARIOUS and even a game of Quidditch involving the audience! MINUTES! THEATER “SUPERB... WITTY... MEMORABLE... FULL OF LOVE AND EMOTION” - LondonTheatre “FANTASTIC! FESTIVE MOTOWN LEGENDS AND FULL-ON!” - The Guardian “ Motown royalty warms the winter night… the one you want to hear”– Chicago Tribune “ A perfect Christmas gift to top the season” – HuffPost Chicago Make your holiday season shine as two of America’s performing royalty take to the stage. Original Supreme, Mary Wilson and The Four Tops will be singing, dancing and Critically acclaimed -

Annual Report 2016/17

annual report 2016/17 a year in review 2016/17 Joni Mitchell: River conceived and directed by allen macinnis, music arranged by greg lowe, set and costume designer dana osborne, lighting designer Artistic Highlights jason hand, sound designer michael laird. The 2016/17 season was the first year for Dennis Garnhum as the incoming Artistic Director of the Grand. The proudly Canadian season was crafted and planned by the outgoing Artistic Director, Susan Ferley, in honour of Canada’s celebration of 150 years since Confederation. The opening event of the season was the High School Project. Susan Ferley’s final production, Les Misérables School Edition, was an incredible celebration of the young talent in our region. The pro- duction showcased vocal and acting talents and enjoyed sold-out houses and standing ovations. The opening night included a tribute to Ferley – a wonderful acknowledgement of her 15 years of artistic contributions here at the Grand. The subscription series began with the sounds of one of Canada’s beloved musicians in the pro- brendan wall duction of Joni Mitchell: River. Three outstanding singers — Louise Pitre, Emm Gryner, and Brendan Wall — sang a collection of Joni’s songs accompanied by a powerful band of musicians. The message was clear: this year we celebrate Canada. On the McManus Stage, Ronnie Burkett’s The louise pitre Daisy Theatre played to sold-out houses for a two-week run in November. This was his first appearance at the Grand and audiences cheered with delight at this master puppeteer improvising and crafting a new show nightly. Due to overwhelming demand, Burkett returned in the 2017/18 season. -

PDF Download

LOUISE PITRE to Star in the Canadian Premiere of THE TOXIC AVENGER Presented by Dancap Productions Inc. TICKETS ON SALE FRIDAY, AUGUST 7 @ 9AM Book & Lyrics by Joe DiPietroMusic & Lyrics by David Bryan Based on Lloyd Kaufman’s “The Toxic Avenger” OPENING NIGHT HALLOWEEN 2009 The Music Hall, Toronto Toronto (August 6, 2009) – Dancap Productions Inc. is pleased to announce that Louise Pitre, Canada’s first lady of musical theatre, will revel in the role of the evil Mayor of Tromaville when the Canadian premiere of the monster musical comedy, THE TOXIC AVENGER, hits the stage of The Music Hall this October. Tickets for THE TOXIC AVENGER will be available beginning Friday, August 7 at 9am, and can be purchased by calling 416.644.3665 or online at http://www.toxicavengertoronto.com/. Multi award-winning singer and actress Louise Pitre catapulted to national fame in 1992 when she portrayed legendary French singer Edith Piaf, in three different productions of Piaf, which followed her star turn as Fantine in the Toronto production of Les Misérables. She has had a career rich with success, recognized with several Dora Mavor Moore Awards in Toronto, a National Broadway Touring Award in New York, a special award from the San Francisco Theatre Critics Circle, a New York Theatre World Award and a Tony nomination for her role as Donna Sheridan in Mamma Mia!. In 2001, after wowing audiences in Toronto, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, Pitre made her Broadway debut (playing the part for two years) when Mamma Mia! opened at New York’s Winter Garden Theatre. -

Broadway Bound Marie, Dancing Still: a New Musical Will Be Presented at the 5Th Avenue Theatre March 22Nd – April 14Th and You Get a 25% Discount!

Broadway Bound Marie, Dancing Still: A New Musical will be presented at The 5th Avenue Theatre March 22nd – April 14th and you get a 25% discount! One of the things that makes The 5th Avenue Theatre such a special place, is the fact that nine of its shows have made their way to Broadway! Marie, Dancing Still: A New Musical is getting polished up to be number ten, and you can see it first, and with your discount! Just visit www.5thavenue.org and put in Promo code: ROTARYSEATTLE to purchase your tickets! You book directly through our website, plus, you also save in fees! Marie, Dancing Still - A New Musical Mar 22 – Apr 14, 2019 Book and Lyrics by Lynn Ahrens Music by Stephen Flaherty Directed & Choreographed by Susan Stroman Broadway visionaries meet ballet royalty. Five-time Tony Award®-winning director and choreographer Susan Stroman (The Producers, Contact), Tony Award®-winning authors Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty (Ragtime, Once On This Island), and acclaimed New York City Ballet principal dancer Tiler Peck invite you backstage into 19th-century Paris, where glittering opulence hobnobbed with underworld dangers. In this era of groundbreaking artistry, a girl named Marie (Peck) dreams of being the next star of the ballet. Despite the odds of her hard-scrabble life, she scrimps, saves and steals in pursuit of her ambitions. But when fate leads her to the studio of Impressionist Edgar Degas, she unknowingly steps into immortality—becoming the inspiration for his most famous sculpture ever: Little Dancer. Also starring Tony Award® nominee Terrence Mann (Pippin), Louise Pitre (Mamma Mia!) and Tony Award® winner Karen Ziemba (Contact), Marie, Dancing Still - A New Musical is the gorgeous new musical poised to conquer the stage—and your heart. -

Gender Equity in Canadian Theatre

Email: [email protected] Website: www.eit.playwrightsguild.ca Steering Committee: Cole Alvis (IPAA), Aliyah Amarshi (PACT Diversity Committee), Joanna Falck (LMDA), Sedina Fiati (CAEA Diversity Committee), Lynn McQueen (CAEA), Lisa O’Connell (PTD), Achieving Equity in Canadian Theatre: Lena Recollet (IPAA), A Report with Best Practice Arden Ryshpan (CAEA), Recommendations Meg Shannon (PACT), Sheila Sky (ADC), charles c. smith (CPAMO), Donna-Michelle St. © April 2015 Bernard (The Ad Hoc Assembly), and Heidi Taylor (PTC) Co-Organizers: Rebecca Burton (PGC), Laine Zisman Newman (PTD) Prepared by Michelle MacArthur Metcalf Intern: Jennie Egerdie (PGC) Lead Researcher: Dr. Michelle MacArthur EIT Research Report 2 Table of Contents List of Tables and Charts ............................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary..................................................................................................... 6 Study Highlights .......................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 10 Where are all the women? ............................................................................................................. 10 Equity in Theatre ..........................................................................................................................