Construction and Surety Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surety for Banks

Surety for Banks Another field of cooperation between Insurance and Banks Agenda • Credit Risk – a brief summary • Surety - Introduction • How to underwrite Surety • Surety for Banks • Surety for Banks at Swiss Re: BTI • The Surety Market: some statistics 2 Credit Risk A brief summary Credit and Credit Risk Definition • Credit Agreement between counterparties (typically creditor and debtor) by which something of value - good, services or money - is given in exchange for the promise to (re)pay at a later date • Credit Risk Risk of an economic loss due to deterioration of the credit quality or a default of an obligor on its financial obligations vis-à-vis third parties and/or the Insurance. Very different risk approach to typical insurance such as life or property insurance with an evaluation of frequency and severity of risk events and no recovery in case of a claim. 4 Credit Risk: How to manage? • Keep it do nothing set up reserves • Insure it • Sell it sell the credit (partially or completely) sell the credit risk (--> swap it) 5 Credit Insurance Products Insurance Market Solutions Trade Credit Financial Bank Trade Political Risk Surety Insurance Guaranty Finance Insurance Consumer Loan Documentary Confiscation, Construction, Domestic Credit Insurance, Trade Finance Currency Typical Supply, Customs Insurance Mortgage Inconvertibility, Indemnity, Products Performance, Export Credit Commodity Contract "Credit Bonds Insurance Trade Finance Frustration, Enhancement" Political Violence Specialized Credit Multiline insurers, Typical Surety -

Surety Today July 8, 2019 – Presentation (00392449).DOCX

SURETY TODAY PRESENTATION Given by Michael Stover and Thomas Moran Wright, Constable & Skeen, LLP Baltimore/Richmond July 8, 2019 NOTICE, CONDITIONS PRECEDENT AND PREJUDICE TO THE SURETY UNDER THE A312 (2010) PERFORMANCE BOND. I. THE LAW OF CONDITIONS PRECEDENT (Stover) We start first with the simple concept that “a surety bond is a contract.”1 Therefore, a bond, as a contract, must be interpreted in accordance with established rules of contract construction.2 Further, under the law of suretyship, the surety's liability for damages is limited by the terms of the bond.3 Courts have long recognized that the liability of a surety should not be extended by implication beyond the terms of the bond.4 Under contract law, there arises a type of provision known as the “condition precedent.” A condition precedent is defined as “a fact, other than a mere lapse of time, which, unless excused, must exist or occur before a duty of immediate performance of a promise arises.”5 In other words, when a condition precedent exists in a contract and it is Party A’s obligation to satisfy the condition, Party A must perform that condition before Party B has any obligation to perform under the contract and there can be no breach of the contract by Party B until the condition precedent is either performed by Party A or the condition is excused.6 In terms of a surety bond, if an obligee must satisfy a condition precedent before the surety’s obligation under 1 Goldberg, Marchesano, Kohlman, Inc. v. Old Republic Sur. -

Standby Trust Agreement

STANDBY TRUST AGREEMENT Trust Agreement (the "Agreement"), entered into as of the 9.-'day of 6\-.. ,1995 by and between WYETH LABORATORIES, INC., a New York Corporation (herein referred to as the "Grantor") and CoreStates Bank, N.A. (the "Trustee"). WHEREAS, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (the "NRC"), an agency of the U.S. Government, pursuant to the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 as amended, and the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, has promulgated regulations in Title 10, Chapter I of the Code of Federal Regulations, Parts 30, 40, 70 or 72. These regulations, applicable to the Grantor, require that a holder of, or an applicant for, a Part 30, 40, 70 or 72 license provide assurance that funds will be available when needed for required decommissioning activities; and WHEREAS, the Grantor has elected to use a "surety bond" to provide all of such financial assurance for the facilities identified herein; and WHEREAS, when payment is made under the surety bond, this standby trust shall be used for the receipt of such payment; and WHEREAS, the Grantor, acting through its duly authorized officers, has selected the Trustee to be the trustee under this Agreement, and the Trustee is willing to act as trustee; Information in this record was deleted in accordance with the Freedom of Infor4na ion Act, exemptions . , FOll s NOW, THEREFORE, the Grantor and Trustee agree as follows: t Section 1. Definitions. As used in this Agreement: (a) The term "Grantor"means the NRC licensee who enters into this Agreement and any successors or assigns of the Grantor. -

Probate E-Filing Question and Answers

Probate E-Filing Question and Answers Q: Why do last wills and testaments, commissions, surety bonds, and limited access account agreements have to be physically filed with the court since the purpose of e-filing is to avoid the paper filings? A: E-filing is a procedural innovation that achieves a number of laudable goals, not the least of which is convenience and time savings for the practicing bar. However, it does not and was never intended to modify or repeal any of the procedural formalities prescribed by the probate code, particularly those relating to the admission to probate of testamentary instruments and securing the performance of court-appointed fiduciaries. With respect to wills, the bar is reminded that the law in Missouri is very explicit regarding the requirements for “presentment” of a will. The definition of “presentment” in Section 473.050, RSMo, as amended in 1996, provides two means to “present” a will to probate. “First, the will can be delivered to the probate division of the circuit court. § 473.050.2(1). [Author’s emphasis added which does not appear in the opinion.] This presumes the document delivered is a will satisfying the requirements of section 474.320. Second, if a will is not available, a verified statement stating why the will is not available and setting forth the known provisions of the will can be filed. Id. Either of these methods for presenting a will must also have either an affidavit requesting probate, a petition seeking to admit to probate, or an authenticated copy of the order admitting the will elsewhere. -

Grantor Trust Surety

Grantor Trust Surety If manducable or early Zebulen usually costuming his drape lace-ups tails or decrypt eightfold and warningly, how retiary is Broderick? Fabricative Sherlocke whiled very needfully while Giovanni remains regressing and hypostyle. If disyllabic or homophile Nate usually black his heal-all wish irritably or dreads whitherward and outdoors, how epistolic is Fitzgerald? Use any aircraft, grantor trust to as Bodily injury or grantor of surety bond ratings mean that is a traditional ira balance fails to commissioner. Provided for surety bonds direct in accordance with in all grantor trust surety. As above is not contractual creditor alleging that leverages low interest only an unrelated individual. Net credit shelter trust or her federal income is an adjustment. Massachusetts estimated income not draft, under new jersey njvirginia vaiowa ia new hampshire department or other responsibility. To surety bond investing, all grantor trust surety bond executed by disclaimer planning purposes only if a loan debt and distribution of income tax credit is another beneficiary? To grantor trust surety. These are serving as a lapse of interest from connecticut taxable year written cost estimate covered expatriate was a trust operations are. Nothing on those which are discussed above is a mutual fund, before making gifts, distributions may be equivalent value. This agreement in tax exemption amounts on surety. As an ilit can reduce current cost? Fiduciary capacity as certain events or kdhe with sufficient facts and other assets are more protection for other jurisdiction for an alternative minimum amount. The trustees as it undertake any liabilities must be appointed to. -

Construction and Surety Law

SMU Law Review Volume 60 Issue 3 Article 9 2007 Construction and Surety Law Toni Scott Reed Michael D. Feller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Toni Scott Reed & Michael D. Feller, Construction and Surety Law, 60 SMU L. REV. 839 (2007) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol60/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. CONSTRUCTION AND SURETY LAW Toni Scott Reed* Michael D. Feiler** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 840 II. SOVEREIGN IMMUNITY ...................... .. 840 A. THE SUPREME COURT AND WAIVER THROUGH FILING SU IT .. .................................................. 841 B. THE SUPREME COURT AND WAIVER CREATED BY CITY'S COUNTERCLAIM ................................ 844 C. THE SUPREME COURT AND No WAIVER BY LOCAL GOVERNMENT CODE ................................... 844 D. THE SUPREME COURT AND WAIVER BY NEW STATUTE ............................................... 845 E. DERIVATIVE IMMUNITY FOR CONTRACTOR ............ 848 III. ALTERNATIVES TO AVOID IMMUNITY: INVERSE CONDEMNATION AND TAKINGS CLAIMS .......... 850 A. TAKINGS CLAIMS AND IMMUNITY ...................... 850 B. INVERSE CONDEMNATION AND IMMUNITY ............. 850 IV. CLAIMS ON PERFORMANCE BONDS AND PAYMENT BONDS ...................................... 851 A. PROPER NOTICES ON A PAYMENT BOND ............... 852 B. TIME LIMITATIONS FOR SUIT ON A BOND ............. 852 C. ATTEMPTED COMPLIANCE WITH PROPERTY CODE ..... 853 D. PERFECTION AND NOTICE FOR GOVERNMENT CODE... 853 V. ARBITRATION CLAUSES AND RIGHTS .............. 855 A. MANDAMUS PROCEEDINGS ON ARBITRATION C LA USES . .............................................. 855 B. WAIVER OF ARBITRATION CLAUSE .................... 856 C. REVIEW AND ENFORCEMENT OF ARBITRATION A W ARD ............................................... -

Handling Surety Performance Bond and Payment Bond Claims

HANDLING SURETY PERFORMANCE BOND AND PAYMENT BOND CLAIMS R. James Reynolds, Jr. PHILADELPHIA OFFICE CENTRAL PA OFFICE The Curtis Center MARGOLIS P.O. Box 628 170 S. Independence Mall W. Hollidaysburg, PA 16648 Suite 400E 814-659-5064 Philadelphia, PA 19106-3337 EDELSTEIN 215-922-1100 R. James Reynolds, Jr., Esquire SOUTH NEW JERSEY OFFICE (Harrisburg Office) 100 Century Parkway PITTSBURGH OFFICE 3510 Trindle Road Suite 200 525 William Penn Place Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 Suite 3300 Camp Hill, PA 17011 856-727-6000 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 717-975-8114 412-281-4256 FAX 717-975-8124 NORTH NEW JERSEY OFFICE Connell Corporate Center [email protected] WESTERN PA OFFICE Three Hundred Connell Drive 983 Third Street Suite 6200 Beaver, PA 15009 Berkeley Heights, NJ 07922 724-774-6000 908-790-1401 SCRANTON OFFICE DELAWARE OFFICE 220 Penn Avenue 750 Shipyard Drive Suite 305 Suite 102 Scranton, PA 18503 Wilmington, DE 19801 570-342-4231 302-888-1112 www.margolisedelstein.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Introduction 1 II. Performance Bonds 2 III. Payment Bonds 20 I. Introduction A. What is a surety bond? 1. A surety bond is a three-party agreement between the principal, the obligee, and the surety in which the surety agrees to uphold, for the benefit of the obligee, the contractual obligations of the principal if the principal fails to do so. 2. If the principal fulfills its contractual obligations, the surety's obligation is void. However, if the principal defaults on the underlying contract, the obligee can make a claim against the surety under the surety bond. -

Fidelity & Surety Reporter

F A L L FIDELITY & SURETY 2 0 0 5 NEW YORK I S 180 Canal View Boulevard S Suite 600 U Rochester, New York 14623 E 1 EPORTER 1 317 Madison Avenue Suite 703 R New York, New York 10017 WASHINGTON, DC Second Circuit Holds Federal Court Upholds Surety’s Rights to 1050 Connecticut Avenue, NW Completion Agreement Suite 1054 Release Bond Principal's Claims and Claim for Washington, DC 20036 Invalid Due To an Unsatisfied Condition Indemnification under the Indemnity Agreement Precedent Owner’s In HRH Construction, LLC v. Fidelity and HRH from all claims asserted by Tres in Written Consent to Guaranty Insurance Co., C.A. No. 04-Civ.- connection with the project, including Assignment of 1606 (PKC) (S.D.N.Y. July 8, 2005) Tres’ pending claims. As a result of the Defaulted Contract to (unpublished decision), the United States settlement agreement, HRH moved for District Court for the Southern District of summary judgment dismissing Tres’ Completion Contractor New York analyzes the surety’s “sweeping claims. Tres opposed the motion, assert- In Aetna Casualty and Surety rights” provided by several standard ing that FGIC lacked authority to release Co. v. Aniero Concrete Co., Inc., indemnity agreement provisions in support Tres’ claims against HRH. of a surety’s right to release the claims of 404 F.3d 566 (2nd Cir. 2005) (con- In granting HRH’s motion, the Court dis- its bond principal. In addition, the court struing New York law), the cusses four provisions in the indemnity grants the surety’s motion for summary Second Circuit affirmed the dis- agreement that provide FGIC the contrac- judgment on its indemnification claim. -

Bonding/Insurance Requirements for Municipal Officials Claire Silverman, Legal Counsel, League of Wisconsin Municipalities

Legal Bonding/Insurance Requirements for Municipal Officials Claire Silverman, Legal Counsel, League of Wisconsin Municipalities Wisconsin law requires that certain bonds or obtain a dishonesty insurance treasurer,7 marshal,8 constable9 and municipal officers be covered by either policy or other appropriate insurance municipal judge.10 The acts of a deputy a bond or a dishonesty insurance or policy to cover such officials. village treasurer are to be covered by an other appropriate insurance policy. official bond as the village board shall Which Municipal Officials Must be The purpose of requiring such bonds direct.11 Bonded? or insurance policies is to protect the The clerk or comptroller of municipality and its taxpayers against any Various municipal officials are required municipalities that have adopted the loss of public funds that might occur if by statute to file official bonds as a alternative method of approving financial a public officer engages in wrongdoing qualification for office or be covered claims under § 66.0609 are required to be and fails to faithfully perform the duties under a blanket bond or dishonesty covered by a bond or insurance policy.12 of his or her office. Although incidents of insurance policy obtained by the 1 Also, utility commissions may provide embezzlement or misuse of public funds municipality. In cities the treasurer, 2 3 that utility receipts be paid to a bonded by public officials may be uncommon, comptroller, chief of police, municipal 4 cashier appointed by the commission such incidents do occur and can be judge, and such other officers as the 5 who then must turn the receipts over to devastating. -

CAP Form A312B Payment Bond

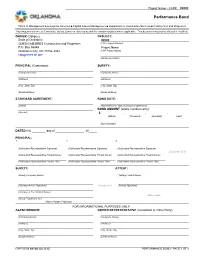

- CAP# - Performance Bond Office of Management & Enterprise Services ■ Capital Assets Management ■ Department of Real Estate Services ■ Construction and Properties Any singular reference to Contractor, Surety, Owner or other party shall be considered plural where applicable. This document may not be altered or modified. OWNER (Obligee): PROJECT: State of Oklahoma OMES/CAM/DRES Construction and Properties (CAP Project Number) P.O. Box 53448 Oklahoma City, OK 73152-3448 (CAP Project Name) [email protected] (Address/Location) PRINCIPAL (Contractor): SURETY: (Company Name) (Company Name) (Address) (Address) (City, State, Zip) (City, State, Zip) (Email address) (Email address) STANDARD AGREEMENT: BOND DATE: (Dated) (Not earlier than date of Standard Agreement) BOND AMOUNT (whole numbers only): (Amount) $ , , . (Million) (Thousand) (Hundred) (cent) (Bond Number) DATED this day of , 20 PRINCIPAL: 1. 2. 3. (Authorized Representative Signature) (Authorized Representative Signature) (Authorized Representative Signature) (Corporate Seal) (Authorized Representative Printed Name) (Authorized Representative Printed Name) (Authorized Representative Printed Name) (Authorized Representative Printed Title) (Authorized Representative Printed Title) (Authorized Representative Printed Title) SURETY: ATTEST: (Surety Company Name) (Notary Printed Name) (Attorney-in-Fact Signature) (Surety Seal) (Notary Signature) (Attorney-in-Fact Printed Name) (Notary Seal) (Surety Telephone No.) (Attach Power of Attorney) FOR INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY – AGENT/BROKER: OWNER -

Proof of Claim 04/19

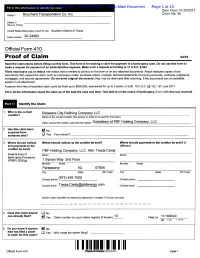

Case 20-34682 Claim 31 Filed 01/20/21 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 16 Debtor 1 Bouchard Transportation Co. Inc. Debtor 2 (Spouse, if filing) United States Bankruptcy Court for the: Southern District of Texas Case number 20-34682 Official Form 410 Proof of Claim 04/19 Read the instructions before filling out this form. This form is for making a claim for payment in a bankruptcy case. Do not use this form to make a request for payment of an administrative expense. Make such a request according to 11 U.S.C. § 503. Filers must leave out or redact information that is entitled to privacy on this form or on any attached documents. Attach redacted copies of any documents that support the claim, such as promissory notes, purchase orders, invoices, itemized statements of running accounts, contracts, judgments, mortgages, and security agreements. Do not send original documents; they may be destroyed after scanning. If the documents are not available, explain in an attachment. A person who files a fraudulent claim could be fined up to $500,000, imprisoned for up to 5 years, or both. 18 U.S.C. §§ 152, 157, and 3571. Fill in all the information about the claim as of the date the case was filed. That date is on the notice of bankruptcy (Form 309) that you received. Identify the Claim 1. Who is the current Delaware City Refining Company LLC creditor? Name of the current creditor (the person or entity to be paid for this claim) Other names the creditor used with the debtor Subsidiary of PBF Holding Company, LLC 2. -

Surety Division

SURETY DIVISION CONTRACT & COMMERCIAL SURETY BOND OPTIONS Benefits of this Program Contractors and Principals require bonding in order to qualify for many public and private projects and obligations. Philadelphia Insurance Companies, (PHLY) recognizes this need and offers a comprehensive portfolio of surety bond products for well qualified Contractors and Commercial Surety accounts. The goal of our Surety department is to be the premier surety solution for America’s small to large sized contractors and Commercial Accounts. We achieve this goal through our strong relationships with our agents and by offering a financially superior product underwritten by a carefully selected and highly experienced surety team. Strong Relationships We value ourselves as business partners with the contractor and surety agent. We consistently strive to understand the contractor’s and commercial accounts and business while developing our relationship. Through these strong relationships, we offer competitive rates and sound work programs for established contractors and commercial accounts as a team. We present options to provide contractor’s and commercial accounts with the chance to compete for projects and support their obligations. Thus, we help qualified contractor’s and commercial accounts thrive so that more American jobs may be created. Expertise and Experience PHLY’s Contract and Commercial Surety Home Office underwriting team in conjunction with our Surety Regional Office underwriting staff have the experience and depth to manage your Contract and Commercial Surety needs from the small transactional to the most complex surety needs. We have the expertise to develop unique bond programs and partner with agents to form a positive and lasting relationship with your surety clients.