Module Note—Market Segmentation, Target Market Selection, and Positioning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point of Sale: the Heart of Retailing

POINT OF SALE: THE HEART OF RETAILING Analysis and insights on the latest trends in retail: artificial intelligence, Quick Service Restaurants, and more Capgemini has deep expertise in retail and digital transformation. This is a proficiency developed over countless projects, including those centered on a critical element of retail technology: the Point of Sale. Whether it is called Point of Sale, Point of Service, Point of Contact, or some similar name that encompasses both online and offline purchases, the goal is a financial transaction and, regardless of the name, the interaction with the customer is what ultimately matters most. The market for Point of Sale (POS) evaluation of their POS solution Intel has positioned solutions has changed dramatically only once every 10 to 15 years, over the last couple of years. there is limited knowledge and the following Acquisitions, omnichannel strategy, experience available to complete market trends as demand for a lower Total Cost of the evaluation internally. Ownership (TCO), introduction of influencing the need cloud-based POS solutions, and To help retailers accelerate the for innovative POS the need for real-time analytics POS vendor selection process, capabilities have transformed the Capgemini has developed a proven solutions: industry. As a result, retailers are methodology. The Capgemini POS increasingly confused about the tool, supported by Intel, is a crucial • New store experience-focused route to take when selecting a part of this process. Using this tool capabilities in an era of new POS solution. Just taking the and Capgemini’s methodology, omnichannel commerce most recent Forrester Wave: Point retailers are able to reduce the of Service report or Gartner Magic time taken from identifying a long • Customer demand for Quadrant can provide a starting list of potential vendors to making frictionless experiences, point with some insight on leading their final selection. -

Winning at Segmentation Strategies for a Digital Age 2

Winning at Segmentation Strategies for a Digital Age 2 Abstract Segmentation has long been considered a basic exercise to understand customers, competitors and the operating environment to enable businesses to make the most of market opportunities and minimize threats or business risks. Over the years segmentation approaches have evolved and broadened using a variety of metrics including simple demographics, behavioral, psychographic, needs-based, and profitability-based or a combination of these. However, these approaches have certain limitations that impede their efficacy. Moreover, the present context of changing consumer behavior, heightened brand competition and growing influence of the digital medium is forcing organizations to rethink their approach towards segmentation. Organizations are looking for models that can help them overcome the challenging task of discerning consumer buying behavior in relation to organizational capabilities and competitive standing. We believe that organizations need to take a fresh look at their approach towards segmentation. This approach is contingent on a ‘Value From’ and ‘Value To’ criteria that flows from design to action across various stages of the segmentation approach. Organizations should assess their current state comprehensively and then design a multi-dimensional segmentation framework. They should then develop a clear value proposition, define and deliver their capabilities and finally ensure continuous measurement. Segmentation should be spread across the organization; understanding the customer should be a way of life and a fundamental driver of shareholder value. 3 Winning at Segmentation The Changing State of Segmentation Segmentation is widely acknowledged as a fundamental needs requires a thorough understanding of customer component of understanding and addressing an requirements. -

Customer Focus Through Market Segmentation

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv International Business Master Thesis No 2001:43 Customer Focus through Market Segmentation - The Case of Volvo CE and the Recycling/Waste Management Segment Daniel Nilsson and Josef Olsson Graduate Business School School of Economics and Commercial Law Göteborg University ISSN 1403-851X Printed by Novum Grafiska ii "Try not to become a man of success, but rather try to become a man of value." - Albert Einstein iii ABSTRACT Today, companies operating in heavy manufacturing industries experience more complex market situations. Customers are becoming more sophisticated and the competition is increasing. In order to survive, companies must become aware of how value is generated for customers to be able to satisfy their needs. An implementation of a market segmentation approach is a useful tool in becoming more customer focused, as it creates a better ability to identify how value is generated for customers in a segment and adjust its activities in order to provide solutions for their needs. In order to see how value is generated in a segment and how a company can adapt its marketing and sales activities according to that knowledge, we have used Volvo CE and the recycling/waste management segment. To find out how value is generated for customers in this segment, we have used a theoretical framework consisting of customer-perceived value and its influencers organisational buying behaviour and positioning. We have created a framework that can be used by a company in the heavy manufacturing industry to identify how customer-perceived value is generated in a specific segment. -

TARGET MARKETS for RETAIL OUTLETS of LANDSCAPE PLANTS Steven C

SOUTHERN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS JULY 1990 TARGET MARKETS FOR RETAIL OUTLETS OF LANDSCAPE PLANTS Steven C. Turner, Jeffrey H. Dorfman, and Stanley M. Fletcher Abstract male shoppers by age and education as an effective Merchandisers of landscape plants can increase retail strategy. With respect to landscape plants, the effectiveness of their marketing strategies by Turner investigated the influence of socioeconomic identifying target markets. Using a full information characteristics on retail purchases, while Gineo ex- maximum likelihood tobit procedure on a system of amined the characteristics of plants that influence three equations, target markets for different types of landscaper and retailer purchases. retail outlets in Georgia were identified. The results The objective was to investigate the socioeco- lend support and empirical evidence to the premise nomic characteristics of consumers that can be used that different retail outlet types have different target by different types of landscape plant retailers to markets and thus should develop different market segment their markets. This information can be used strategies. The estimated target markets are identi- in identifying different target markets, which could fled and possible marketing strategies suitable for lead to more efficient allocation of marketing and each type of retail outlet are suggested. advertising resources. Key words: landscape plants, target markets, THE MODEL simultaneous equations, tobit. Identifying target markets is important to retailers rT' u-, o ea of landscape plants (Phelps; Altorfer). The success he success of retail merchandisers in identifying of various retailer decisions, such as store location, target markets is important to plant growers. Orna- product pricing, and advertising strategies, are de- mental horticulture grower cash receipts grew from pendent on a better understanding of clientele. -

Restaurant Business Plan Template

Restaurant Business Plan Template 2021 The restaurant business plan is a crucial first step in turning an idea for a restaurant into an actual business. Without it, investors and lenders will have no way of knowing if the business is feasible or when the restaurant will become profitable. Business plans span dozens (or even hundreds) of pages, and due to the stakes that lie within the document and the work required to write it, the process of writing a restaurant business plan can threaten to overwhelm. That’s why BentoBox has created a restaurant business plan template for aspiring restaurant owners. This template makes creating a business plan easier with section prompts for business plan essentials like financial projections, market analysis and a restaurant operations overview. Download the Template Restaurant Business Plan 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 04 Leadership Team 05 Restaurant Business Overview 06 Industry & Market Analysis 07 Marketing Strategy 08 Operating Model 09 Financial Overview & Projections 11 Appendix & Supporting Documentation 12 Business Plan Glossary 13 Restaurant Business Plan 3 Executive Summary The executive summary provides a 1-2 page overview of the restaurant and its business model. While the details of how the restaurant will succeed will be explained throughout this business plan, this section will both prove the legitimacy OVERVIEW of the restaurant idea while encouraging investors to enthusiastically read through the rest of the plan. Some specific topics that might be covered in the executive summary include: • Restaurant name, service type and menu overview. • A quick mention of why the leader of the restaurant business is positioned to help it succeed. -

Downtown Lebanon Market Analysis & Business Development Plan

Downtown Lebanon Market Analysis & Business Development Plan May 2011 Acknowledgements This project was made possible in part by financial assistance provided by USDA Rural Development and by in-kind contributions from the City of Lebanon and Lebanon Partners for Progress. Downtown Lebanon Retail Market Analysis & Business Development Plan i Contents Introduction................................................................................................... 1 Methodology...............................................................................................................1 Survey Research........................................................................................... 2 Shopper Survey Summary ...........................................................................................2 Business Owner Survey Summary...............................................................................3 Downtown Assessment............................................................................. 4 Overview of Downtown Lebanon Environment ...........................................................4 Competitive Assessment..............................................................................................5 Market Supply............................................................................................... 7 Market Demand..........................................................................................10 Target Markets ..........................................................................................................10 -

Selling the Abercrombie and Fitch Image

Driessen UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research VIII (2005) Message Communication in Advertising: Selling the Abercrombie and Fitch Image Claire E. Driessen Faculty Sponsor: Scott Dickmeyer, Department of Communication Studies ABSTRACT Advertising is a frequently used influential and persuasive means of communication, especially on teens and young adults. Abercrombie and Fitch is a corporation whose advertising methods have been controversial because of the profound effect its message has on the target audience of teens and young adults. Research found Abercrombie and Fitch used its new campaign to communicate four prevalent messages: The look of an Abercrombie & Fitch Person, The one and only Abercrombie & Fitch, The Abercrombie & Fitch life of luxury, and Not making the Abercrombie & Fitch cut. These messages were communicated through numerous venues, and persuaded consumers to purchase the products through identification with the Abercrombie & Fitch image. Keywords: content analysis, message communication, Abercrombie & Fitch, identification INTRODUCTION Less than one year ago Abercrombie & Fitch decided to remove its main form of advertising, the magalog A&F Quarterly, from the market. The controversy created around this company’s advertising is intriguing. The way a company communicates its image to consumers is an interesting method of message communication. Image by itself is “multidimensional constructs containing cognitive and emotional elements” (p. 86). Corporate image also includes “the extent to which each marketing instrument contributes to the brand image and the extent to which that image enhances desired economic behavior of markets” (p.83). Additionally it encompasses “the quality of management, corporate leadership, and employee orientation” (Haedrich, 1993, p.83). This research study will examine the messages communicated to sell the Abercrombie and Fitch image, this will be done by analyzing the messages sent through Abercrombie & Fitch’s advertising and how these messages are packaged. -

Specialty Foods Marketing & Packaging

SPECIALTY FOODS MARKETING & PACKAGING 101 Shermain Hardesty, UC Davis Ag Economics & UC Small Farm Program MARKETING IS ALL ABOUT…. Market research & Pricing planning Advertising, demos, Target market public relations, identification promotional events Product development Distribution Label & packaging Evaluation design SPECIALTY FOODS Specialty foods are niche products Specialty food categories Cottage Foods http://ucanr.edu/sites/cottagefoods/ Organic, sustainably produced, local ingredients, farmstead Ethnic GMO-free/no artificial ingredients Special health needs COMPETITION Fierce competition in the food industry for shelf space & the consumer’s dollar Differentiation is essential 4Ps of the marketing mix are tools for effective differentiation PURPOSE OF DOING MARKET RESEARCH Understand marketplace consumer characteristics, needs & attitudes competitors' products, strengths & weaknesses Guide in developing marketing plan New product testing BASIC TYPES OF MARKET RESEARCH Sales trends by product category Taste testing Consumers’ product usage and attitudes Specialty Foods Trends source: 2015 State of the Specialty Foods Industry Hot Healthy Ingredients Jackfruit is catching on as a fiber-heavy meat alternative to use in tacos, wraps Avocados are showing up in alternate forms, such as dips, dressings and portable mini meals Grain-free wraps based on almonds, cassava, vegetables and coconuts offer alternatives for people avoiding grains Local Now…?? Tomorrow DISTRIBUTORS ON: Appeal of Local Food Offers greater transparency and trust Is fresher and more seasonal Tastes good Supports the local economy and community The Why Behind the Buy • Innovative and exciting attributes appeal to specialty food consumers, but taste is consistently the No. 1 reason for trying a new product, cited by 65% of survey respondents. • 62% noted they like to try new things. -

5 Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

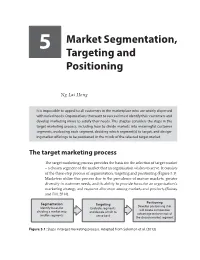

Market Segmentation, 5 Targeting and Positioning Ng Lai Hong It is impossible to appeal to all customers in the marketplace who are widely dispersed with varied needs. Organisations that want to succeed must identify their customers and develop marketing mixes to satisfy their needs. This chapter considers the steps in the target marketing process, including how to divide markets into meaningful customer segments, evaluating each segment, deciding which segment(s) to target, and design- ing market offerings to be positioned in the minds of the selected target market. The target marketing process The target marketing process provides the basis for the selection of target market – a chosen segment of the market that an organisation wishes to serve. It consists 84 Fundamentalsof the three-step of Marketing process of segmentation, targeting and positioning (Figure 5.1). Marketers utilise this process due to the prevalence of mature markets, greater diversity in customer needs, and its ability to provide focus for an organisation’s marketing strategy and resource allocation among markets and products (Baines and Fill, 2014). Segmentation Positioning Targeting Develop positioning that Identify bases for Evaluate segments will create competitive dividing a market into and decide which to advantage in the minds of smaller segments serve best the chosen market segment Figure 5.1: Steps in target marketing process. Adapted from Solomon et al. (2013). 86 Fundamentals of Marketing The benefits of this process include the following: Understanding customers’ needs. The target marketing process provides a basis for understanding customers’ needs by grouping customers with similar characteristics together and for the selection of target market. -

Market Segmentation

Ch11-H8566.qxd 8/8/07 2:04 PM Page 222 CHAPTER 11 Market segmentation YORAM (JERRY) WIND and DAVID R. BELL All markets are heterogeneous. This is evident from the focus of a significant part of the marketing observation and from the proliferation of popular research literature. The basic concept of segmenta- books describing the heterogeneity of local and tion (as articulated, e.g. in Frank et al., 1972) has global markets. Consider, for example, The Nine not been greatly altered. And many of the funda- Nations of North America (Garreau, 1982), Latitudes mental approaches to segmentation research are and Attitudes: An Atlas of American Tastes, Trends, still valid today, albeit implemented with greater Politics and Passions (Weiss, 1994) and Mastering volumes of data and some increased sophistica- Global Markets: Strategies for Today’s Trade Globalist tion in the modelling method. To see this, consider (Czinkota et al., 2003). When reflecting on the nature the most compelling and widely used approach to of markets, consumer behaviour and competitive product design and market segmentation – con- activities, it is obvious that no product or service joint analysis. The essence of the approach out- appeals to all consumers and even those who pur- lined in Wind (1978) is still evident in recent work chase the same product may do so for diverse rea- by Toubia et al. (2007) that uses sophisticated geo- sons. The Coca Cola Company, for example, varies metric arguments and algorithms to improve the levels of sweetness, effervescence and package size efficiency of the method. Other advances use for- according to local tastes and conditions. -

Part 2: 2-2 Micro Trends Emphasizing the Target Consumer

Part 2: 2-2 Micro Trends Emphasizing the Target Consumer The microenvironment consists of: a) the company, b) suppliers of the company, c) marketing intermediaries, d) other groups impacting business, e) employees and management, f) competitors, and g) target consumers. The buyer must constantly track all these factors. Each impact, in some degree, decisions concerning the creation of a profitable Six Month Merchandise plan. The Company This scan begins with observing what is happening in the company itself, especially with top management’s philosophy and direction. Since executive management approves or sometimes sets the parameters for the business operations, buyers must consider all happenings in the store and then determine the type of impact any actions or activities may have on their particular departments or the product classifications which they are purchasing. The retail store is organized into five divisions: management, merchandising, sales promotion, finance, and human resources. Executive management must ensure that all employees have the same concept of the store image, the target consumer, and their merchandising and management philosophy, as well as the marketing strategy for the store. It is very important for the buyer to understand how to work with executive management and with store management in order to achieve the highest gross margin and profit for her/his specific departments. For example, if management must eliminate job positions or trim employee hours in order to meet payroll, the buyer must determine the impact on the functioning of, and sales in, the department. Buyers always want to work closely with the sales promotion division (i.e., advertising, visual merchandising, special events and promotions, fashion training, publicity) in order to make major decisions concerning the marketing of their products – media type, how many spots to be purchased, when to schedule the media, etc. -

Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning By Mark Anthony Camilleri 1, PhD (Edinburgh) How to Cite : Camilleri, M. A. (2018). Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning. In Travel Marketing, Tourism Economics and the Airline Product (Chapter 4, pp. 69-83). Springer, Cham, Switzerland. Abstract Businesses may not be in a position to satisfy all of their customers, every time. It may prove difficult to meet the exact requirements of each individual customer. People do not have identical preferences, so rarely does one product completely satisfy everyone. Therefore, many companies may usually adopt a strategy that is known as target marketing. This strategy involves dividing the market into segments and developing products or services to these segments. A target marketing strategy is focused on the customers’ needs and wants. Hence, a prerequisite for the development of this customer-centric strategy is the specification of the target markets that the companies will attempt to serve. The marketing managers who may consider using target marketing will usually break the market down into groups (segments). Then they target the most profitable ones. They may adapt their marketing mix elements, including; products, prices, channels, and promotional tactics to suit the requirements of individual groups of consumers. In sum, this chapter explains the three stages of target marketing, including; market segmentation (ii) market targeting and (iii) market positioning. 4.1 Introduction Target marketing involves the identification of the most profitable market segments. Therefore, businesses may decide to focus on just one or a few of these segments. They may develop products or services to satisfy each selected segment.