Stuffed Deer and the Grammar of Mistakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Investigative Committee on Oversight Report

HISTORY OF THE COMMITTEE The House Special Investigative Committee on Oversight (the Committee) was formed by Speaker Todd Richardson on February 27, 2018, and consists of seven members: Chairman Jay Barnes, Vice-chairman Don Phillips, Ranking Member Gina Mitten, Rep. Jeanie Lauer, Rep. Kevin Austin, Rep. Shawn Rhoads, and Rep. Tommie Pierson Jr. House Resolution 5565, adopted by a unanimous vote of the House of Representatives on March 1, 2018, established procedures for the Committee. In particular, HR 5565 empowered and required the Committee to “investigate allegations against Governor Eric R. Greitens” and “report back to the House of Representatives within forty days of such committee being appointed[.]” It further permitted the Committee to close all or a portion of hearings to hear testimony or review evidence, and to redact testimony transcripts and other evidence to protect witness identities or privacy. Subpoenas were issued to compel the appearance of witnesses and the production of documents. Every witness before the Committee testified under oath. • On February 22, 2018, Speaker Todd Richardson indicated he would form a committee to investigate allegations against Governor Greitens (Greitens). In response, counsel for Greitens stated that they would “welcome reviewing this issue with the independent, bipartisan committee of the Missouri House of Representatives.” Counsel promised to “work with the committee,” after faulting the Circuit Attorney for the City of St. Louis for refusing to meet with Greitens.1 • On February 27, 2018, the Committee was formed by Speaker Todd Richardson. • On February 28, 2018, Chairman Barnes made contact with attorneys Ed Dowd, Counsel for Greitens; Scott Simpson, counsel for Witness 1; and Al Watkins, counsel for Witness 3. -

The Manor House: a Novel

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 The Manor House: A Novel Cleo Rose Egnal Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Fiction Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Egnal, Cleo Rose, "The Manor House: A Novel" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 308. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/308 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Manor House: A Novel Senior Project submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Cleo Egnal Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my family and friends for being so utterly supportive of this project. To my parents: for reading draft after draft, and for instilling in me a passion for books. To my professors: for continuing to impress in me a love for learning, and broadening my intellectual horizons. Most of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Porochista Khakpour, without whom this novel would still be a twelve-page short story tucked away in my college portfolio. -

To Tell the Truth Ethical and Practical Issues in Disclosing Medical Mistakes to Patients Albert W

JGIM PERSPECTIVES To Tell the Truth Ethical and Practical Issues in Disclosing Medical Mistakes to Patients Albert W. Wu, MD, MPH, Thomas A. Cavanaugh, PhD, Stephen J. McPhee, MD, Bernard Lo, MD, Guy P. Micco, MD While moonlighting in an emergency room, a resident risk management committee, rather than to the patient. physician evaluated a 35-year-old woman who was 6 More recently, the American College of Physicians Ethics months pregnant and complaining of a headache. The Manual states, “physicians should disclose to patients in- physician diagnosed a “mixed tension/sinus headache.” The patient returned to the ER 3 days later with an in- formation about procedural and judgment errors made in tracerebral bleed, presumably related to eclampsia, and the course of care, if such information significantly affects died. the care of the patient.”6 The AMA’s Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs states, “Situations occasionally occur in which a patient suffers significant medical complica- tions that may have resulted from the physician’s mistake rrare humanum est : “to err is human.” In medical or judgment. In these situations, the physician is ethically E practice, mistakes are common, expected, and under- required to inform the patient of all facts necessary to en- standable.1,2 Virtually all practicing physicians have sure understanding of what has occurred.”7 made mistakes, but physicians often do not tell patients In this article, we analyze the various ethical argu- or families about them.3,4 Even when a definite mistake ments for and against disclosing serious mistakes to pa- results in a serious injury, the patient often is not told. -

Spot the Mistake Activity

An Amazing Fact a Day! Spot the Mistake When pencils were first invented, moist bread was used to erase any mistakes! Read the sentences below. Can you spot the spelling, grammar and punctuation mistakes? 1. There not in they’re house because their over they’re, in the park. 2. The golden sands felt warm and soothing beneth my worn out and weary feet. Their where beads of condensation dripping from my cold refreshing glass off water. 3. You’re car is blocking are drive. Our you going to move it soon. I think your being most inconsiderate! 4. Swaying in the wind, the trees dances to the rythm of the storm. The moon looked down on the danced trees and smiled in ameusment at the glittering stars. 5. Running and smiling the children jumped out of the school and into the crystal wite blanket covering of snow. The glittering sn owflakes shined and twinkled as the children ranned past. Page 1 of 2 6. She was whereing a beautifull diamond ring. 7. The twins decided that for there birthday thei each wanted a smartphone. they’re parents decided they were to young for such an ecspensive gift. Begrudginly the twins agreed to a trip to the cinema with their friends. 8. They’re house was the sppokyest looking house on are street. It had an angry face a creaky door a broken roof and an uninviting demeanour. You could also try to find out: • how the erasing power of rubber was discovered; • when rubbers were first put on the end of pencils; • how many pencils and erasers are made and sold in your country each year. -

Metamora Hunt Newsletter April 2016

Metamora Hunt Newsletter April 2016 www.metamorahunt.com Hounds & Hunting By Joe Maday, MFH Contact Information: Honorary Secretary: Michelle Mortier: 586-914-5802 [email protected] Masters of Fox Hounds Mr. Joe Maday: 810.678.8384 Mr. Ken Matheis: 248.431.4093 Mrs. Deborah Bates Pace: 810.678.8762 The Fairly Hunted award is given out each year by Hunts go out every Wednesday, Saturday the Masters of Fox Hounds Association to and select Mondays mid- August to mid- acknowledge riders under the age of 18 who have April, weather permitting. Please contact hunted at least 5 times in that season. [email protected] for a complete list of locations, dates and times. This year’s recipients from the Metamora Hunt are: Always call the Hunt Hotline: 810.678.2711 for weather or information updates on any Amber Brown Hunt related event. Grace Charnstrom Nellie Charnstrom Amanda Greening Jessica Greening Sydney Moore Kalie Ryan Metamora Hunt Horse Show Madison Sparks Kati Sullivan Christopher Westgate Congratulations to them all as they are the future of our sport. Additional News: We will be hosting our 84th annual Horse Show on June 10-12th at Win a Gin Farm Metamora Hunt Country Magazine Ads: on Delano Rd. The Hunt welcomes our Landowners, Sponsors, Advertisers, Advertising copy deadline is April 15, 2016. Exhibitors, Benefactors, Social Members, and Friends of the Hunt to join our Our Magazine is a wonderful resource and tabletop Members for this beautiful and interesting keepsake of the year! Be sure to be included, by event. running an ad for your business, a thank you, a Memorial or a fun ad to remember this year. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York

Case 1:20-cv-00651-GLS-DJS Document 57 Filed 10/09/20 Page 1 of 153 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK REV. STEVEN SOOS, REV. NICHOLAS STAMOS, ) JEANETTE LIGRESTI, as parent and guardian of infant ) plaintiffs P.L. and G.L, DANIEL SCHONBRUN, ) ELCHANAN PERR, MAYER MAYERFELD, MORTON ) AVIGDOR, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) ANDREW M. CUOMO, Governor of the State of New York, in ) his official capacity; LETITIA JAMES, Attorney General of the ) Case No. State of New York in her official capacity; KEITH M. ) 1:20-cv-00651-GLS-DJS CORLETT, Superintendent of the New York State Police, in his ) official Capacity; HOWARD A. ZUCKER, M.D., New York ) State Commissioner of Health, in his official capacity; BETTY ) A. ROSA, Interim Commissioner of the New York State ) Education Department, in her official capacity; EMPIRE ) STATE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION (“ESD”), a New ) York State Public Benefit Corporation; BILL DE BLASIO, ) Mayor of the City of New York, in his official capacity; DR. ) DAVE A. CHOKSHI, New York City Commissioner of Health, ) in his official capacity; TERENCE A. MONAHAN, Chief of ) the New York City Police Department, in his official capacity; ) RICHARD CARRANZA, Chancellor of the New York City ) Department of Education in his official capacity. ) Defendants. FIRST AMENDED VERIFIED COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE AND DECLARATORY RELIEF Plaintiffs, by and through their counsel, complain as follows: NATURE OF ACTION 1. This First Amended Complaint adds new parties and further claims in this civil rights action, which challenges a series of executive orders issued by defendant Governor Andrew M. -

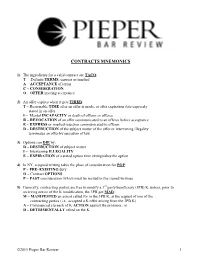

Contracts Mnemonics

CONTRACTS MNEMONICS 1) The ingredients for a valid contract are TACO: T – Definite TERMS, express or implied A – ACCEPTANCE of terms C – CONSIDERATION O – OFFER inviting acceptance 2) An offer expires when it gets TIRED: T – Reasonable TIME after an offer is made, or after expiration date expressly stated in an offer I – Mental INCAPACITY or death of offeror or offeree R – REVOCATION of an offer communicated to an offeree before acceptance E – EXPRESS or implied rejection communicated to offeror D – DESTRUCTION of the subject matter of the offer or intervening illegality terminates an offer by operation of law 3) Options can DIE by: D – DESTRUCTION of subject matter I – Intervening ILLEGALITY E – EXPIRATION of a stated option time extinguishes the option 4) In NY, a signed writing takes the place of consideration for POP: P – PRE–EXISTING duty O – Contract OPTIONS P – PAST consideration (which must be recited in the signed writing) 5) Generally, contracting parties are free to modify a 3rd party beneficiary (3PB) K, unless, prior to receiving notice of the K modification, the 3PB got MAD: M – MANIFESTED an assent called for in the 3PB K, at the request of one of the contracting parties (i.e., accepted a K offer arising from the 3PB K) A – Commenced a breach of K ACTION against the promisor, or D – DETRIMENTALLY relied on the K ©2015 Pieper Bar Review 1 6) Contract assignments may involve the ADA: A – ASSIGNMENT of a contractual right to collect money owed under the K D – DELEGATION of the performance required under the K A – ASSUMPTION -

The Mistake Hunter

THE MISTAKE HUNTER THE 50 MISTAKES THAT KILL A STARTUP This book is dedicated to our mistakes because there is no one path to success, you should find your own; but there are some mistakes to be avoided, in order to build your own path to success. Sincerely; Lorenzo Castagnone Niccolò Mascaro September, 2017 CEO of D.A.N. Content Introduction 1. Pingjam (a monetization solution for Android app developers) 2. StartupSQUARE (a platform for helping entrepreneurs) 3. Cusoy (restaurant meal planner based on your dietary needs) 4. Unifyo (a tool for high performing sales team) 5. Everpix (photo hosting service) 6. Gowalla (location-based social network) 7. Sonar (social discovery app) 8. Formspring (Q&A social network) 9. EventVue (online community for conferences) 10. Devver (developer coding tools) 11. FindIt (universal search across files stored in the cloud) 12. Canvas Networks (image-centric social website) 13. Blurtt (photo sharing app ) 14. Admazely (advertising for web shops) 15. Pumodo (mobile sports platform) 16. Dijiwan (digital marketing company) 17. Prim (laundry delivery) 18. InBloom (student data management) 19. Outbox (mail digitizing service) 20. Argyle (social media marketing software) 21. Bloom.fm (mobile music service) 22. Stipple (Image-tagging advertising) 23. Delight (usability testing for mobile apps) 24. How.Do (DIY crafts ideas and projects) 25. Readmill (social reading app) 26. Plancast (social site for planning events) 27. Flud (social news reader) 28. DrawQuest (drawing app / game) 30. Standout Jobs (recruiting portal) 32. Flowtab (mobile drink ordering) 33. Shnergle (real time reconnaissance platform) 34. YouCastr (video platform) 35. Admazely (tools for re-targeting advertisement) 36. -

8 Ways to Manage Your Mental Health As In-House Counsel

8 Ways to Manage Your Mental Health as In-house Counsel Skills and Professional Development 1 / 6 The pandemic has been rough, especially for lawyers who already face high levels of anxiety. With the emotional stress of long work hours coupled with being locked down for the past two months, mental health in the legal field is a waning commodity, much like hand sanitizer. 2 / 6 But the mental well-being of in-house counsel has been top-of-mind for ACC long before the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Thirty-three percent of lawyers have been diagnosed with a mental illness, ranging from anxiety to depression and bipolar disorder to schizophrenia. While these numbers are disquieting, there are ways in-house counsel can alleviate these symptoms. In honor of Mental Health Awareness month, we’ve compiled the top eight pieces of advice in-house counsel can use to manage their mental health during and after the pandemic. Keep in mind that these tips are not meant to replace therapy, but they can help make the obstacles you may be facing more surmountable. 1. Make time for yourself Between your massive workload and never-ending to-do list at home, the last thing you have time for is yourself. But taking care of yourself is not selfish. You need to be at the top of your mental game to deliver consistently in all areas of your life. To avoid burnout, dedicate 10-15 minutes each day to doing something fun that recharges you, whether it’s gardening or learning new tricks on Photoshop. -

The Same Selling Mistakes-Final

THE SAME SELLING MISTAKE FOR 50 YEARS WHY YOUR SALES REPS & CHANNEL PARTNERS STRUGGLE TO SELL MORE PREPARED BY CHRIS BENNETT This white paper is broken into seven sections. The purpose is to introduce a new perspective on driving massive revenue growth. 1. Discover the big problem. 2. The big dilemma. 3. How big is this selling problem? 4. How did we get here? 5. Where do we go from here? 6. The golden opportunity ahead. 7. Low risk method for driving massive revenue growth. This is 01 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY / THE PROBLEM especially important for manufactures, How professional sales people work is continuously evolving. Or is that just an illusion? Digital transformation, new research about how buyers buy, the sales rep tech stack, new vendors, consumption models, new sales methodologies, more information than ever before all change how sales pros work. telcos & But one thing is not changing; Selling Mistakes. master agents This is especially important for manufactures, vendors, telcos and master agents who rely who rely on on channel partners for the bulk of their selling. channel partners for the bulk of their selling. The big selling mistake being made 50 years ago is still the main one being made today. Tragically, by the majority of all sales pros and channel sellers; the research below is overwhelming evidence of that. At Chris Bennett Sales Training I have seen it with my own eyes too having trained 10’s of thousands of sales pros in 75-80 corporations over the past 26 years. Many people think that for the last 50 years selling has been primarily dominated by a consultative selling approach first developed by Mack Hanan in the 70’s. -

The Hunt: a Short Story

255 The Hunt A Short Story Josephine Donovan I’d get my rifle down days beforehand and start cleaning it. Dad used to kid me. It doesn’t take that long to clean a rifle, he’d say. But I always got so excited. Sometimes I think it’s the preparation, the anticipation that’s the most exciting part. But I couldn’t wait for opening day. I’d set up a practice range behind the house and tack up an old camouflage jacket on the barn. I’d aim right for the top button. I wanted to be at my optimum for when the real hunt began. It was the best time of year. The turning leaves cast a golden- orange glow, the atmosphere was crisp, there was a smoky smell in the air as folks were starting up their wood stoves. That’s when “buck fever” sets in. The old adrenalin gets pumping and you feel super alive. It’s my favorite season. No one who hasn’t done it can understand the thrill of the hunt. I believe it has to do with our early hominid origins. In those days they had to hunt in order to live. Of course, there were berries and nuts and grasses which the women gathered. But the real food came from the hunters, who were men. They had to be out there every single day. No time restrictions, no hunting “seasons.” Hunting was 24-7. What a life! Sometimes I wish I’d lived then. It makes you feel like you’re getting back to your primitive origins when you’re hunting, back to your natural self, away from all the artificial restraints of modern life. -

Case 1:20-Cv-06539-JMF Document 243 Filed 02/16/21 Page 1 of 105

Case 1:20-cv-06539-JMF Document 243 Filed 02/16/21 Page 1 of 105 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------------- X : 20-CV-6539 (JMF) IN RE CITIBANK AUGUST 11, 2020 WIRE : TRANSFERS : FINDINGS OF FACT AND : CONCLUSIONS OF LAW ---------------------------------------------------------------------- X JESSE M. FURMAN, United States District Judge: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2 FACTUAL FINDINGS .................................................................................................................. 4 A. The 2016 Term Loan .......................................................................................................... 4 B. The May and June 2020 Transactions ................................................................................ 7 C. The Events of August 11, 2020 ........................................................................................... 9 D. Citibank’s Response to the August 11th Wire Transfers .................................................. 16 E. Defendants’ Responses to the August 11th Wire Transfers ............................................. 19 F. The UMB Bank Lawsuit .................................................................................................... 26 G. Procedural History ............................................................................................................ 27