Download Fulltext

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perov and Mussorgsky 1834-1882 and 1839-1881

This translation is published on koudasheva.com and on the blog ‘From the Music Cabinet’. Perov and Mussorgsky 1834-1882 and 1839-1881 Vladimir Vasilyevich Stasov First published in ‘Russian Antiquity’ [Русская старина] Volume 38 № 5, May 1883. 433-458. Accessed: https://runivers.ru/bookreader/book199538/#page/449/mode/1up [Владимир Васильевич Стасов: Перов и Мусоргский] Translation: Nadia Koudasheva1 -------- Venerable Mikhail Ivanovich, I ask you to provide some space in ‘Russian Antiquity’ [Русская Старина] for a few of my pages where I attempt to study and compare two of our great artistic individuals, in part using already publicised materials, and in part using those which have not appeared in print before. Both of these artists have already passed away into eternity, and hence they directly represent ‘material’ for ‘Russian Antiquity’, but it is the contents which they consistently instilled into their creations and which was always drawn from our old serfdom life, which represent national material. Since it is often with great interest and compassion that your readers meet the thoughts, judgements, assessments, and characterisations coming from the mouths of the multitude of personalities who have passed away long ago and who are passing through your journal in a rotating gallery, then maybe they will also find some interest in the thoughts and characterisations coming from people who although are still living, but are such that will aid in the complete understanding and definition of those great personalities who are already no more and who indeed belong to history. V. S. -------- I. To my surprise no one in our country has expressed this yet, but Perov and Mussorgsky display an amazing parallelism in the Russian artistic world. -

Audience Guide, Beauty and the Beast

Audience Guide Choreography by Lew Christensen Staged by Leslie Young Music by Pyotr I. Tchaikovsky The Benedum Center for the Performing Arts February 14 - 23, 2020 Artists: Hannah Carter, Alejandro Diaz | Photo: Duane Rieder Created by PBT’s Department of Education and Community Engagement, 2020 The Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre Education Department is grateful for the support of the following organizations: Allegheny Regional Asset District Highmark Foundation Anne L. and George H. Clapp Charitable Trust BNY Jack Buncher Foundation Mellon Foundation Peoples Natural Gas Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Eat ‘n Park Hospitality Group Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Edith L. Trees Charitable Trust Development ESB Bank Pittsburgh Cultural Trust Giant Eagle Foundation PNC Bank—Grow up Great The Grable Foundation PPG Industries, Inc. Hefren-Tillotson, Inc. Richard King Mellon Foundation James M. and Lucy K. Schoonmaker The Heinz Endowments Henry C. Frick Educational Fund of The Buhl Foundation Contents 2 The Origins of Beauty and the Beast 3 Select List of Beauty and the Beast Adaptations 4 About the Ballet 5 Synopsis 6 The Music 6 The Choreography 9 The Répétiteur 9 Costumes and Sets 12 Theater Programs 12 Theater and Studio Accessibility Services 1 The Origins of Beauty and the Beast When it was published in 1740, Beauty and the Beast was a new take on an centuries-old canon of stories, fairy tales and myths, found in all cultures of the world, about humans who fall in love with animals. Maria Tatar, author of Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World, notes that these stories - about love, courtship, romance, marriage - give “a vivid, visual grammar for thinking about abstractions: cruelty and compassion, hostility and hospitality, predators and victims.”* They explore issues that are “as old as time:” the layers, complexities and contradictions at the heart of relationships. -

Fairy Tales Retold for Older Readers

Story Links: Fairy Tales retold for Older Readers Fairy Tales Retold for Older Readers in Years 10, 11 and 12 These are just a few selections from a wide range of authors. If you are interested in looking at more titles these websites The Best Fairytale Retellings in YA literature, GoodReads YA Fairy Tale Retellings will give you more titles. Some of these titles are also in the companion list Fairy Tales Retold for Younger Readers. Grimm Tales for Young and Old by Philip Pullman In this selection of fairy tales, Philip Pullman presents his fifty favourite stories from the Brothers Grimm in a clear as water retelling, making them feel fresh and unfamiliar with his dark, distinctive voice. From the otherworldly romance of classics such Rapunzel, Snow White, and Cinderella to the black wit and strangeness of such lesser-known tales as The Three Snake Leaves, Hans-my-Hedgehog, and Godfather Death. Tinder by Sally Gardiner, illustrated by David Roberts Otto Hundebiss is tired of war, but when he defies Death he walks a dangerous path. A half beast half man gives him shoes and dice which will lead him deep into a web of dark magic and mystery. He meets the beautiful Safire, the scheming Mistress Jabber and the terrifying Lady of the Nail. He learns the powers of the tinderbox and the wolves whose master he becomes. But will all the riches in the world bring him the thing he most desires? This powerful and beautifully illustrated novel is inspired by the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale, The Tinderbox. -

The Russian Literary Fairy Tale 163

SNEAK PREVIEW For additional information on adopting this title for your class, please contact us at 800.200.3908 x501 or [email protected] Revised First Edition Edited by Th omas J. Garza University of Texas, Austin Bassim Hamadeh, CEO and Publisher Michael Simpson, Vice President of Acquisitions Jamie Giganti, Managing Editor Jess Busch, Graphic Design Supervisor Marissa Applegate, Acquisitions Editor Jessica Knott, Project Editor Luiz Ferreira, Licensing Associate Copyright © 2014 by Cognella, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereaft er invented, including photocopying, microfi lming, and recording, or in any informa- tion retrieval system without the written permission of Cognella, Inc. First published in the United States of America in 2014 by Cognella, Inc. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Cover: Viktor M. Vasnetsov, Copyright in the Public Domain. Ivan Yakovlevich Bilibin, Copyright in the Public Domain. Viktor M. Vasnetsov, Copyright in the Public Domain. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62661-362-1 (pbk)/ 978-1-62661-363-8 (br) Contents Preface vii By Thomas J. Garza INTRODUCTION: ORIGINS OF THE RUSSIAN FOLKTALE 1 Th e Russian Magical World 3 By Cherry Gilchrist STRUCTURAL APPROACHES: THE FORM OF THE FOLKTALE 13 Folklore as a Special Form of Creativity 15 By Peter Bogatyrëv and Roman Jakobson On the Boundary Between Studies of Folklore and Literature 25 By Peter Bogatyrëv and Roman Jakobson Fairy Tale Transformations 27 By Vladimir Propp PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACHES: MEANING AND MIND IN THE TALES 43 A Method of Psychological Interpretation 45 By Marie-Louise von Franz FEMINIST APPROACHES: THE ROLES OF FEMALE FIGURES IN THE TALES 49 Feminist Approaches to the Interpretation of Fairy Tales 51 By Kay F. -

Top 150 Global Licensors Report for the Very First Time, Debuting at No

APRIL 2018 VOLUME 21 NUMBER 2 Plus: The Walt Disney Company Tops Report at $53B 12 Licensors Join the Top 150 GOES OUTSIDE THE LINES Powered by Crayola is much more than a crayon. The iconic brand has strengthened its licensing program to ensure it brings meaningful products for people of all ages to market for years to come. This year, Crayola joins License Global’s Top 150 Global Licensors report for the very first time, debuting at No. 116. WHERE FASHION AND LICENSING MEET The premier resource for licensed fashion, sports, and entertainment accessories. Top 150 Global Licensors GOES OUTSIDE THE LINES Crayola is much more than a crayon. The iconic brand has strengthened its licensing program to ensure it brings meaningful products for people of all ages to market for years to come. This year, Crayola joins License Global’s Top 150 Global Licensors report for the very first time, debuting at No. 116. by PATRICIA DELUCA irst, a word of warning for prospective licensees: Crayola Experience. And with good reason. The Crayola if you wish to do business with Crayola, wear Experience presents the breadth and depth of the comfortable shoes. Initial business won’t be Crayola product world in a way that needs to be seen. Fconducted through a series of email threads or Currently, there are four Experiences in the U.S.– conference calls, instead, all potential partners are asked Minneapolis, Minn.; Orlando, Fla.; Plano, Texas; and Easton, to take a tour of the company’s indoor family attraction, Penn. The latter is where the corporate office is, as well as the nearby Crayola manufacturing facility. -

FAIRY TALES RETOLD Selected Fairy Tales Retold for Readers in Years 7 - 9

Story Links: Fairy Tales Retold for Younger Readers This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY FAIRY TALES RETOLD Selected fairy tales retold for readers in Years 7 - 9 The Sisters Grimm series by Michael Buckley The Fairytale Detectives; The Unusual Suspects; The Problem Child; Once Upon a Crime; Magic and Other Misdemeanors; Tales from the Hood The main characters in this series are Sabrina and Daphne Grimm, descendants of the Brothers Grimm and the stories revolve around the idea that these girls were recording a history of magical phenomena. The fairy tale characters are based on real creatures called ‘Everafters’ which fell under the spell of the powerful magic worked by Wilhelm Grimm and the witch Baba Yaga who kept them prisoners in the small town of Ferryport Landing where at least one of the Grimm family’s descendants must always live. The Selection series by Kiera Cass The Selection; The Elite; The One; The Heir; The Prince and The Guard; Happily Ever After; The Crown A series of novels loosely based on Cinderella. It follows the journey of America Singer, a young girl who is chosen to enter a competition called ‘The Selection’, (The Hunger Games meets The Bachelor, minus the blood sport) which is supposed to help the heir to the throne find their partner for life. In America's case, she is chosen to be one of the thirty- five girls to compete for Prince Maxon's heart. However, she already has a partner back home and is thus stuck between the two worlds and realizes that life as one of the competitors is not what she expected. -

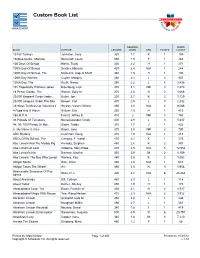

Custom Book List

Custom Book List MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT 10 Fat Turkeys Johnston, Tony 320 1.7 K 1 159 10-Step Guide...Monster Numeroff, Laura 450 1.5 F 1 263 100 Days Of School Harris, Trudy 320 2.2 H 1 271 100th Day Of School Schiller, Melissa 420 2.4 N/A 1 248 100th Day Of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 340 1.5 H 1 190 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 360 2.1 L 2 937 100th Day, The Krulik, Nancy 350 2.2 L 4 3,436 101 Hopelessly Hilarious Jokes Eisenberg, Lisa 370 3.1 NR 3 1,873 18 Penny Goose, The Walker, Sally M. 370 2.8 N 2 1,066 20,000 Baseball Cards Under... Buller, Jon 330 2.7 K 2 1,129 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea Bowen, Carl 470 2.5 L 3 2,232 23 Ways To Mess Up Valentine's Wesley, Valerie Wilson 490 2.6 N/A 4 8,085 4 Pups And A Worm Seltzer, Eric 350 1.5 H 1 413 763 M.P.H. Fuerst, Jeffrey B. 410 2 NR 3 760 88 Pounds Of Tomatoes Neuschwander, Cindy 400 2.9 L 3 1,687 98, 99, 100! Ready Or Not... Slater, Teddy 310 1.7 J 1 432 A. My Name Is Alice Bayer, Jane 370 2.4 NR 2 700 ABC Mystery Cushman, Doug 410 1.9 N/A 1 218 ABCs Of My School, The Campoy, F. Isabel 430 2.2 K 1 275 Abe Lincoln And The Muddy Pig Krensky, Stephen 480 2.6 K 2 987 Abe Lincoln At Last! Osborne, Mary Pope 470 2.5 N/A 5 12,553 Abe Lincoln's Hat Brenner, Martha 330 2.9 M 2 1,159 Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved Winters, Kay 480 3.5 K 2 1,052 Abigail Spells Alter, Anna 480 2.6 N/A 1 610 Abigail Takes The Wheel Avi 390 3.5 N 3 1,958 Abominable Snowman Of Pas- Stine, R. -

The Scarlet Flower (Аленький Цветочек)

The Scarlet Flower (Аленький цветочек) Once upon a time as a merchant set off for market, he asked each of his three daughters what she would like as a present on his return. The first daughter wanted a brocade dress, the second a pearl necklace, but the third, whose name was Beauty, the youngest, prettiest and sweetest of them all, said to her father: «All I’d like is a rose you’ve picked specially for me!» When the merchant had finished his business, he set off for home. However, a sudden storm blew up, and his horse could hardly make headway in the howling gale. Cold and weary, the merchant had lost all hope of reaching an inn when he suddenly noticed a bright light shining in the middle of a wood. As he drew near, he saw that it was a castle, bathed in light. «I hope I’ll find shelter there for the night,» he said to himself. When he reached the door, he saw it was open, but though he shouted, nobody came to greet him. Plucking up courage, he went inside, still calling out to attract attention. On a table in the main hall, a splendid dinner lay already served. The merchant lingered, still shouting for the owner of the castle. But no one came, and so the starving merchant sat down to a hearty meal. Overcome by curiosity, he ventured upstairs, where the corridor led into magnificent rooms and halls. A fire crackled in the first room and a soft bed looked very inviting. -

SAINT-PETERSBURG DIGEST July 2017

SAINT-PETERSBURG DIGEST July 2017 1 Contents Dear Friends, The midsummer is the best time for going out of town. Even if there’s the rain, people are trying to find a timeslot to get away and spend some time in nature or even to swim. But the ones that stay in the city shouldn’t be disappointed - there are lots of different events going on. So, let’s take a look at them. Depeche Mode, Imagine Dragons and Usadba Jazz concerts will prove that July is a true month of musical festivals and big concerts. Opera lovers will be fascinated by the gala-concert “Viva-Mozart” which fully consists of the main operas of the famous author. And the Ballet fans should definitely attend “Up & Down” ballet by Boris Eifman. Don’t miss your chance to discover new sides of Van Gogh’s and Edvard Munch’s lives in the new form of video-exhi- bition this month. Cinema chapter will please those who were waiting for “Dunkirk”, the latest movie by Christopher Nolan and “The Dark Tower”, which is the latest screen adaptation of Stephen King novel staring Matthew Mcconaughey. Water, sand sculpture and architectural festivals will keep your kids outside and busy. The rainy days can be spent while watching “Despicable Me 3” which has just come out. The Cover Story of this month will tell about The Peterhof State Museum-Reserve. This is another must-see place that will definitely amaze you by its beautiful fountains, sculptures and architecture. We already made Saint-Petersburg easy for you. -

Betsy Hearne Papers, 1941-2017 Graduate School of Library and Information Science, UIUC ID: 18/1/38

1 Box List: Betsy Hearne Papers, 1941-2017 Graduate School of Library and Information Science, UIUC ID: 18/1/38 Arrangement: Series 1: Subject Files, 1842-2009 Series 2: Presentations and Author Talks, 1978-2008 Series 3: Drafts, 1974-2013 Series 4: Center for Children’s Books, 1941-2007 Series 5: Publications, 1977-2017 Series 6: Beauty and the Beast, 1959-2010 Complete Finding Aid: https://archives.library.illinois.edu/archon/index.php?p=collections/controlcard&id=1155 Box list created 2018-01-23 Repository: University Archives University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign http://archives.library.illinois.edu/ _____________________________________________________________________________________ Series 1: Subject Files, 1842-2009 This series contains Betsy Hearne’s correspondence, research files, conference papers, book proposals, VHS and audiocassette tapes, and publisher agreements. It also includes research notes, correspondence and children’s fan mail, two interviews, poems, permissions, and illustrations related to books and articles written by Hearne. In addition, this series includes her teaching materials such as course syllabi, lecture notes, reading lists, and assignments. Of particular importance are course materials and a memory book relating to Hearne’s LEEPlore course, one of the first online classes taught at the Graduate School of Library and Information Sciences. Also included are several folders relating to Hearne's trip to Iran in 1992. Finally, this series contains Hearne’s tenure file from the University of Chicago. Items are listed in alphabetical order. Box 1 1. 2nd Annual GSLIS Storytelling Festival VHS, 2005 2. 13th Annual Reading Round-up, Augusta Civil Center, 2002 3. Lloyd Alexander and other letters, 1981-1992 4. -

Animation and the National Ethos: the American Dream, Socialist Realism, and Russian Émigrés in France

Animation and the National Ethos: the American Dream, Socialist Realism, and Russian émigrés in France by Jennifer Boivin A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Modern Languages and Cultural Studies University of Alberta © Jennifer Boivin, 2017 ii Abstract Animation is seen as the innocent child of contemporary media and is often considered innocuous and juvenile in general popular culture. This might explain why it is still a marginal field. Perhaps this perception is influenced by the mass media of animation being mostly aimed at children, or at least perceived as such. This thesis specifically focuses on animated films’ aesthetic and content in relation to their particular cultural context and ethos, or national ideology. I investigate the American Dream, Soviet Socialism, and a Russian émigré ethos in France to show how seemingly similar content can carry unique ideological messages in different cultural contexts. Therefore, my film analyses examine the way animation is used as a medium to carry specific meaning on the screen, expressing this ethos. The national ethos is manifest in beliefs and aspirations of a community, culture, and era, and it promotes a certain cultural unity and order. It is a form of nationalism oriented towards utopian values rather than clear civic or political engagement. It can be politicised as well as individualised. This idealised ethos remains a largely constructed paradigm on which the regular citizen (and the audience) should model his behaviour. In this thesis, I propose that animation is not only a form of entertainment, but also a possible mechanism of social control through national ideas, responding to prevailing cultural and social conditions. -

A TRAGIC TRICKSTER 151 the Trickster As the Underground Author 154 Rituals of Expenditure 167 “I Will Not Explain to You Who Were These Four…” 174

——————————————————— INTRODUCTION ——————————————————— CHARMS OF THE CYNICAL REASON: THE TRICKSTER’S TRANSFORMATIONS IN SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET CULTURE — 1 — ——————————————————— INTRODUCTION ——————————————————— Cultural Revolutions: Russia in the Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Anthony Anemone (The New School) Robert Bird (The University of Chicago) Eliot Borenstein (New York University) Angela Brintlinger (The Ohio State University) Karen Evans-Romaine (Ohio University) Jochen Hellbeck (Rutgers University) Lilya Kaganovsky (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) Christina Kiaer (Northwestern University) Alaina Lemon (University of Michigan) Simon Morrison (Princeton University) Eric Naiman (University of California, Berkeley) Joan Neuberger (University of Texas, Austin) Ludmila Parts (McGill University) Ethan Pollock (Brown University) Cathy Popkin (Columbia University) Stephanie Sandler (Harvard University) Boris Wolfson (Amherst College), Series Editor — 2 — ——————————————————— INTRODUCTION ——————————————————— CHARMS OF THE CYNICAL REASON: THE TRICKSTER’S TRANSFORMATIONS IN SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET CULTURE Mark Lipovetsky Boston 2011 — 3 — A catalog data for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2011 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-934843-45-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-618111-35-7 (digital) Effective June 20, 2016, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses,